Governing a Continent of Trash: the Global Politics of Oceanic Pollution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Assessment Report on Microplastics

An Assessment Report on Microplastics This document was prepared by B Stevens, North Carolina Coastal Federation Table of Contents What are Microplastics? 2 Where Do Microplastics Come From? 3 Primary Sources 3 Secondary Sources 5 What are the Consequences of Microplastics? 7 Marine Ecosystem Health 7 Water Quality 8 Human Health 8 What Policies/Practices are in Place to Regulate Microplastics? 10 Regional Level 10 Outer Banks, North Carolina 10 Other United States Regions 12 State Level 13 Country Level 14 United States 14 Other Countries 15 International Level 16 Conventions 16 Suggested World Ban 17 International Campaigns 18 What Solutions Already Exist? 22 Washing Machine Additives 22 Faucet Filters 23 Advanced Wastewater Treatment 24 Plastic Alternatives 26 What Should Be Done? 27 Policy Recommendations for North Carolina 27 Campaign Strategy for the North Carolina Coastal Federation 27 References 29 1 What are Microplastics? The category of ‘plastics’ is an umbrella term used to describe synthetic polymers made from either fossil fuels (petroleum) or biomass (cellulose) that come in a variety of compositions and with varying characteristics. These polymers are then mixed with different chemical compounds known as additives to achieve desired properties for the plastic’s intended use (OceanCare, 2015). Plastics as litter in the oceans was first reported in the early 1970s and thus has been accumulating for at least four decades, although when first reported the subject drew little attention and scientific studies focused on entanglements, ‘ghost fishing’, and ingestion (Andrady, 2011). Today, about 60-90% of all marine litter is plastic-based (McCarthy, 2017), with the total amount of plastic waste in the oceans expected to increase as plastic consumption also increases and there remains a lack of adequate reduce, reuse, recycle, and waste management tactics across the globe (GreenFacts, 2013). -

Ocean Currents and the Pacific Garbage Patch

ocean currents and the Pacific Garbage Patch photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography The image above shows a net tow sample from the Pacific Garbage Patch. The sample contains small fish and many small pieces of plastic. The Garbage Patch is primarily composed of this small plastic “confetti” suspended throughout the surface water of the North Pacific Gyre, and is not a island of trash as suggested by some media outlets. The region where the trash converges in the center of the North Pacific Gyre, in a region where surface currents are weak and convergent, thus concentrating large amounts of trash in an area estimated to be close to the size of Texas. With this slide I often show a video clip about the Garbage Patch. Although the links may change, here is one from ABC that I’ve used several times: www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFMW8srq0Qk this video is a bit over the top but it gets the point across. There is additional information from Scripps Institution of Oceanography SEAPLEX experiment: http://sio.ucsd.edu/Expeditions/Seaplex/ and several videos on youtube.com by searching the phrase “SEAPLEX” Pacific garbage patch tiny plastic bits • the worlds largest dump? • filled with tiny plastic “confetti” large plastic debris from the garbage patch photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography little jellyfish photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography These are some of the things you find in the Garbage Patch. The large pieces of plastic, such as bottles, breakdown into tiny particles. Sometimes animals get caught in large pieces of floating trash: photo: NOAA photo: NOAA photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography How do plants and animals interact with small small pieces of plastic? fish larvae growing on plastic Trash in the ocean can cause various problems for the organisms that live there. -

Sassen-2015-Expulsion-Brutality-And

EXPULSIONS EXPULSIONS Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy Saskia Sassen THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2014 To Richard Copyright © 2014 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sassen, Saskia. Expulsions : brutality and complexity in the global economy / Saskia Sassen. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 59922- 2 (alk. paper) 1. Economics— Sociological aspects. 2. Economic development— Social aspects. 3. Economic development— Moral and ethical aspects. 4. Capitalism— Social aspects. 5. Equality— Economic aspects. I. Title. HM548.S275 2014 330—dc23 2013040726 Contents Introduction: The Savage Sorting 1 1. Shrinking Economies, Growing Expulsions 12 2. The New Global Market for Land 80 3. Finance and Its Capabilities: Crisis as Systemic Logic 117 4. Dead Land, Dead Water 149 Conclusion: At the Systemic Edge 211 References 225 Notes 269 Acknowledgments 283 Index 285 Introduction The Savage Sorting We are confronting a formidable problem in our global politi cal economy: the emergence of new logics of expulsion. The past two de cades have seen a sharp growth in the number of people, enter- prises, and places expelled from the core social and economic orders of our time. This tipping into radical expulsion was enabled by ele- mentary decisions in some cases, but in others by some of our most advanced economic and technical achievements. The notion of ex- pulsions takes us beyond the more familiar idea of growing in e- qual ity as a way of capturing the pathologies of today’s global capi- talism. -

The Technological Challenges of Dealing with Plastics in the Environment

COMMENTARY The Technological Challenges of Dealing With Plastics in the Environment AUTHORS tem functions, the effects of micro- the Ellen McArthur Foundation push- Sarah-Jeanne Royer plastics are still not fully understood, ing for new plastic economy (https:// Scripps Institution of Oceanography, although they are widely accepted to www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ University of California, San Diego be negative. This is exacerbated by our-work/activities/new-plastics- and The Ocean Cleanup Foundation, the fact that it is difficult (if not im- economy) and global commitments Delft, The Netherlands possible) to remove such microplastics from a list of countries to manage the from the environment. Or, at least, Dimitri D. Deheyn balance between environmental health the technology of today to do so at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and the plastic economy (https:// such a large scale is still not ready. University of California, San Diego www.ellenmacarthurfoundation. Hence, most of the technological in- org/news/a-line-in-the-sand-ellen- novations related to plastic targets macarthur-foundation-launch-global- lastic pollution has been at the the macroplastics only; even though commitment-to-eliminate-plastic- forefront of national news and social P this size fraction might not be the pollution-at-the-source). media with shocking images of wild- most abundant or damaging, at life impacted with plastics. Plastics least, it can be removed and hence are found in remote places, from prevent its further fragmentation in Plastics: Impact on Society mountain tops to the bottom of the the environment. and Public Health Still oceans and from the North Pole to fl In this article, we brie yidentify a Well-Kept Mystery Antarctica, and are a sign of the wide- the technologies that are proposed to Despite being one of the most spread impact of human activities. -

Information Sheet

32nd Annual Conference of the South African Society for Atmospheric Sciences 31 October-1 November Hosts: Climate System Analysis Group (University of Cape Town) Lagoon Beach Hotel in Milnerton, Cape Town. ABSTRACT BOOK Sponsor: i PREFACE The 32nd annual conference of South African Society for Atmospheric Sciences is being hosted in Cape Town, by the Climate System Analysis Group at UCT. The theme for the conference is “Innovation for Information”. It is always a challenging task to know how to translate scientific research/data into useful information. The major aim of the conference is to question, discuss and understand how we traditionally translate research into action and how we could possibly improve on that. We look forward to some interesting and exciting presentations as well as some invigorating discussion after each session. The continuing practice of asking for extended abstracts was very successful this year with over 30 abstract submitted for review and the proceedings of the conference will be published with an ISBN number. The review process was ably led by Prof Willem Landman and our thanks to him and his hard-working reviewers. The conference proceedings will be available for download from the SASAS and SASAS 2016 web-pages. There are also over 30 posters on display and we ask that you engage with them and their authors. Rather spend your tea times there, and catch up with friends and colleagues over meals! On behalf of the SASAS 2016 organising committee, we would like to thank everyone who enthusiastically contributed to the preparation and success of the 32nd Annual SASAS conference. -

THE Environment Management पर्यावरणो रक्षति रतक्षिय賈 a Quarterly E- Magazine on Environment and Sustainabledevelopment (For Private Circulation Only)

THE Environment Management पर्यावरणो रक्षति रतक्षिय賈 A Quarterly E- Magazine on Environment and SustainableDevelopment (for private circulation only) Vol.: IV April - June 2018 Issue: 2 Current Issue: Beat Plastic Pollution Beat Plastic Pollution If you can’t reuse it, refuse it CONTENTS From Director’s Desk Beat the plastic pollution…………2 T. K. Bandopadhyay Cement kiln co-processing facilitates sustainable management We are happy to release current issue of our institute’s newsletter on the theme, ‘Beat of MSW………………………….5 Plastic Pollution’ on World Environment Day. In last five decades plastic has made in Ulhas Parlikar road in our day to day life. From medical devices, electronic gadgets to a bag, its application is everywhere because it is cheap, light weight and can be molded in any Plastics- the modern menace to form. Since 1957, India’s plastic production capacity has increased manifold with over oceans……………………………8 30,000 plastic processing industries that contribute to 0.5% of the GDP and provide C. Maheshwar employment to about 0.4 million people. Despite of its importance, the degradation of plastic is a challenge and its careless disposal is leading to pollution in water bodies, The health risks of plastic and Safe land as well as causing deadly diseases viz. cancer due leaching of chemicals in food Plastic use practices…………… 13 products from plastic containers or allergies due to inhalation of fumes coming out Hari Prakash Srivastava from the open burning of plastic material. At this juncture it is imperative to identify sustainable practices for the management of Biodegradation of plastic……….15 plastic waste. -

Litter in Our Waterways – Factsheet

Litter in our Waterways – Factsheet Marine litter poses a vast and growing threat to the marine and coastal environment. Around 8 million items of litter enter the marine environment every day. 1 An estimated 70 per cent of marine litter ends up on the sea bed, 15 per cent on beaches and the remaining floats to the surface. 1 An estimated 80% of marine debris is from land based sources 20% sea based. These sources fall into four major groups: 1 . Tourism related - food/beverage packaging etc . Waste/stormwater - ex stormwater drains, sewer overflows etc . Fishing related - lines, nets etc . Ship/boat related - waste/garbage deliberately or accidentally dumped overboard It is estimated three times as much rubbish is dumped into the world’s oceans annually as the weight of fish caught. 5 Around 7 billion tonnes of plastic litter enter the ocean every year. 2 It is estimated that over 13, 000 pieces of plastic litter float on every square kilometre of ocean and this figure continues to grow. 8 Plastics make up about 60% of marine debris, with an estimated 100,000 marine mammals and turtles killed by plastic litter every year around the world. 5 Entanglement and ingestion are the primary types of direct damage to wildlife caused by marine litter; it can smother sea beds and it is a source of toxic substances in the marine environment. 1 Available information indicates at least 77 species of marine wildlife found in Australian waters and at least 267 marine species worldwide, are affected by entanglement in or ingestion of marine debris, including 86% of all sea turtles species, 44% of all seabird species and 43% of all marine mammal species. -

Surface Circulation2016

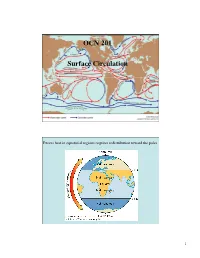

OCN 201 Surface Circulation Excess heat in equatorial regions requires redistribution toward the poles 1 In the Northern hemisphere, Coriolis force deflects movement to the right In the Southern hemisphere, Coriolis force deflects movement to the left Combination of atmospheric cells and Coriolis force yield the wind belts Wind belts drive ocean circulation 2 Surface circulation is one of the main transporters of “excess” heat from the tropics to northern latitudes Gulf Stream http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Newsroom/NewImages/Images/gulf_stream_modis_lrg.gif 3 How fast ( in miles per hour) do you think western boundary currents like the Gulf Stream are? A 1 B 2 C 4 D 8 E More! 4 mph = C Path of ocean currents affects agriculture and habitability of regions ~62 ˚N Mean Jan Faeroe temp 40 ˚F Islands ~61˚N Mean Jan Anchorage temp 13˚F Alaska 4 Average surface water temperature (N hemisphere winter) Surface currents are driven by winds, not thermohaline processes 5 Surface currents are shallow, in the upper few hundred metres of the ocean Clockwise gyres in North Atlantic and North Pacific Anti-clockwise gyres in South Atlantic and South Pacific How long do you think it takes for a trip around the North Pacific gyre? A 6 months B 1 year C 10 years D 20 years E 50 years D= ~ 20 years 6 Maximum in surface water salinity shows the gyres excess evaporation over precipitation results in higher surface water salinity Gyres are underneath, and driven by, the bands of Trade Winds and Westerlies 7 Which wind belt is Hawaii in? A Westerlies B Trade -

Great Pacific Garbage Patch Progression

Great Pacific Garbage Patch Progression: 1. What is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch? 2. How? Throwback to beginning of plastics. 3. Fracking and Oil to get materials for plastic 4. Consequences of fracking for oil and minerals (show the oil spill that happened Friday) 5. Explain the short lifecycle of plastic, disposable 6. Microbeads 7. Where is AWAY? Landfills, oceans, etc. 8. Doesn’t degrade just smaller pieces, ocean slurry zone. 9. Blocks food for phytoplankton, becomes food for larger fish and whales. 10. Consequences of consumption of plastic chemicals/cancer, birth defects. a. Accumulate in fatty tissue, concentrated in humans, b. PCB and DDT attach onto the plastic when they’re in the ocean together. c. PCB is a lubricant used in electricity conductors and will take thousands of years to break down. Language only lasts for 1 thousand. d. DDT was an agrochemical used 40’s-60’s and then banned, but previous uses ran off of soil into water where it still is. Bugs became resistant too. 11. How to help and get back on track/reduse, reuse, recycle. 12. Designs in progress for this problem 13. Our responsibilities as a designer for the future, design for 10 future generations. Images: http://i2.wp.com/savethewater.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/1.jpg http://voices.nationalgeographic.com/files/2016/04/thootpaste.jpg https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a8/Microplastics_impact_on_biological_com munities.png https://plastictides.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/10035153466_dfdd13d962_z.jpg http://s.newsweek.com/sites/www.newsweek.com/files/styles/embed-lg/public/2014/04/22/2014/ -

Productivity and Sustainable Management of the Humboldt Current Large Marine Ecosystem Under Climate Change

Environmental Development 17 (2016) 126–144 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environmental Development journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envdev Productivity and Sustainable Management of the Humboldt Current Large Marine Ecosystem under climate change Dimitri Gutiérrez a,c,n, Michael Akester b,n, Laura Naranjo b a Dirección General de Investigaciones en Oceanografía y Cambio Climático, Instituto del Mar del Perú, IMARPE, Peru b Global Environment Facility (GEF)-UNDP Humboldt Current LME Project, Chile-Peru c Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Programa de Maestría en Ciencias del Mar, Lima, Peru article info abstract Article history: The Humboldt Current Large Marine Ecosystem (HCLME) covers 95% of the southeast Received 14 September 2015 Pacific seaboard of which the area of influence from the Humboldt Current and associated Received in revised form upwelling areas in the Humboldt Current System (HCS) stretches from around 4° to 40° 4 November 2015 south. Global warming will likely affect marine circulation and land-atmosphere-ocean Accepted 5 November 2015 exchanges at the regional level, affecting the productivity and biodiversity patterns along the HCLME. The expected decrease of upwelling productivity in the HCS could be am- Keywords: plified by worldwide trends of oxygen depletion and lower pH. In addition, higher fre- Humboldt-current quency of extreme climatic events, such as El Niño in a warmer ocean, might augment the Coastal-upwelling risks for the recruitment success of anchovy and other short-lived fish resources, espe- Productivity cially in the Northern HCLME. A range of non-climatic anthropogenic stressors also Fisheries Climate-change combines to reduce productivity and biomass yields. -

Reading Handout: the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Reading Handout: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch The world’s oceans are connected by a complex network of water and wind currents, which combine to form gyres. The movement of wind and water in a gyre form large, slowly rotating whirlpools. The North Pacific Gyre is an area of the ocean between the continents of Asia and North America, and its whirlpool-like effect has pulled in pollution from around the world, forming the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a massive accumulation of trash, large and small, in the North Pacific Gyre. {It is like a giant landfill floating in the ocean.} It is a combination of the Western Pacific Garbage Patch, located east of Japan and west of Hawaii, and the Eastern Pacific Garbage Patch, which floats between Hawaii and California. The two are connected by a thin 6,000-mile long current called the Subtropical Convergence Zone, which is also home to a large amount of pollution. The Patch is huge! However it cannot be seen from space, or even an airplane, because it is mostly made up of microplastics floating in the water column. Microplastics are pieces of plastic trash that are smaller than 5mm. Microplastics form when larger plastics break down, or come directly from a manufacturer in the form of nurdles (small plastic pellets used to make other plastic products). Nurdles absorb a lot of toxins as they float in the ocean, and those toxins become concentrated. Researchers estimate that for every 6 pounds (2.72 kilograms) of plastic, there is 1 pound (0.45 kilograms) of plankton. -

6 Ocean Currents 5 Gyres Curriculum

Lesson Six: Surface Ocean Currents Which factors in the earth system create gyres? Why does pollution collect in the gyres? Objective: Develop a model that shows how patterns in atmospheric and ocean currents create gyres, and explain why plastic pollution collects in them. Introduction: Gyres are circular, wind-driven ocean currents. Look at this map of the five main subtropical gyres, where the colors illustrate enormous areas of floating waste. These are places in the ocean that accumulate floating debris—in particular, plastic pollution. How do you think ocean gyres form? What patterns do you notice in terms of where the gyres are located in the ocean? The Earth is a system: a group of parts (or components) that all work together. The components of a system have different structures and functions, but if you take a component away, the system is affected. The system of the Earth is made up of four main subsystems: hydrosphere (water), atmosphere (air), geosphere (land), and biosphere (organisms). The ocean is part of our planet’s hydrosphere, but it is also its own system. Which components of the Earth system do you think create gyres, and why would pollution collect in them? Activity 1 Gyre Model: How do you think patterns in ocean currents create gyres and cause pollution to collect in the gyres? Use labels and arrows to answer this question. Keep your diagram very basic; we will explore this question more in depth as we go through each part of the lesson and you will be able to revise it. www.5gyres.org 2 Activity 2 How Do Gyres Form? A gyre is a circulating system of ocean boundary currents powered by the uneven heating of air masses and the shape of the Earth’s coastlines.