Ritter 1 the Progress Paradox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Concept of the Sun As Ἡγεμονικόν in the Stoa and in Manilius’ Astronomica Nº 21, Sep.-Dec

Eduardo Boechat - Universidade de Brasilia (Brazil) [email protected] The concept of the Sun as ἡγεμονικόν in the Stoa and in Manilius’ Astronomica nº 21, sep.-dec. 2017 BOECHAT, E. (2017). The concept of the Sun as ἡγεμονικόν in the Stoa and in Manilius’ Astronomica. Archai nº21, sep.-dec., p. 79-125 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14195/1984 -249X_21_3 Abstract: Hegemonikon in Stoic vocabulary is the technical term for the chief part or ‘command-centre’ of the soul. As we know, the Stoics considered the cosmos a living organism, and they theorised both about the human soul’s Hegemonikon and about its counterpart in the World-soul. My ultimate purpose in this paper is to show that the Stoic concept of the cosmic hegemonikon can be observed in Manilius’ Astro- nomica. The paper is divided into two parts. To begin with, I will examine and discuss the evidence concerning this concept in the relevant texts of the Early and Middle Stoa. The analysis will indicate that the concept of hegemonikon could involve a background of astronomical theory which some scholars attribute to the Stoic Posidonius. In the second section, I will go on to relate the concept of hegemonikon to the doctrines conveyed by Manilius. Additionally, we shall 79 see that Manilius’ polemic allusions to Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura suggest that the concept was intensely debated in the Post-Hellenistic philosophical circles. Keywords: Ancient Cosmology; Stoics; Manilius; Greek Astrology. nº 21, sep.-dec. 2017 Eduardo Boechat, ‘The concept of the Sun as ἡγεμονικόν in the Stoa and in Manilius’ Astro- nomica.’, p. -

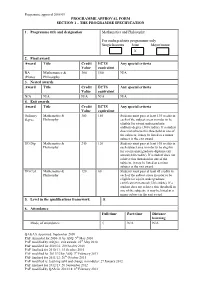

BA Mathematics and Philosophy

Programme approval 2008/09 PROGRAMME APPROVAL FORM SECTION 1 – THE PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION 1. Programme title and designation Mathematics and Philosophy For undergraduate programmes only Single honours Joint Major/minor X 2. Final award Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent BA Mathematics & 360 180 N/A (Hons) Philosophy 3. Nested awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 4. Exit awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent Ordinary Mathematics & 300 150 Students must pass at least 135 credits in degree Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate ordinary degree (300 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award UG Dip Mathematics & 240 120 Students must pass at least 105 credits in Philosophy each subject area in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate diploma exit award (240 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. UG Cert Mathematics & 120 60 Students must pass at least 45 credits in Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate certificate exit award (120 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. 5. Level in the qualifications framework H 6. -

Truth-Bearers and Truth Value*

Truth-Bearers and Truth Value* I. Introduction The purpose of this document is to explain the following concepts and the relationships between them: statements, propositions, and truth value. In what follows each of these will be discussed in turn. II. Language and Truth-Bearers A. Statements 1. Introduction For present purposes, we will define the term “statement” as follows. Statement: A meaningful declarative sentence.1 It is useful to make sure that the definition of “statement” is clearly understood. 2. Sentences in General To begin with, a statement is a kind of sentence. Obviously, not every string of words is a sentence. Consider: “John store.” Here we have two nouns with a period after them—there is no verb. Grammatically, this is not a sentence—it is just a collection of words with a dot after them. Consider: “If I went to the store.” This isn’t a sentence either. “I went to the store.” is a sentence. However, using the word “if” transforms this string of words into a mere clause that requires another clause to complete it. For example, the following is a sentence: “If I went to the store, I would buy milk.” This issue is not merely one of conforming to arbitrary rules. Remember, a grammatically correct sentence expresses a complete thought.2 The construction “If I went to the store.” does not do this. One wants to By Dr. Robert Tierney. This document is being used by Dr. Tierney for teaching purposes and is not intended for use or publication in any other manner. 1 More precisely, a statement is a meaningful declarative sentence-type. -

CC1: Invitation to Philosophy

CC1: Invitation to Philosophy Topic Lectures in terms of Weeks Unit 1: The Nature of Philosophy - 1st-2nd week The Nature of Philosophical Thinking Philosophy as critical Inquiry 2nd-3rd Week Philosophical and Scientific Questions: 3rd-4th Week Differences and Similarities Unit II: Methods in Philosophy - 4th-5th Week Socratic Method Linguistic Analysis 5th- 6th Week Phenomenological Method 6th -7th Week Deconstruction 7th-8th Week Unit III: Fundamental issues in 8th 9th Week Philosophy - Knowledge and Skepticism What is reality? Philosophical Theories of 9th- 11th Week the nature of reality Importance of asking moral questions in 11th- 13th Week everyday Life: Right and wrong, Good life and Happiness Unit IV:Ways of Doing Philosophy in 13th -14th Week the East - Indian Philosophy Chinese Philosophy 14th -15th Week Islamic Philosophy 15th -16th Week CC 2: History of Greek and Medieval Philosophy Topic Lectures in terms of Weeks Unit I: Pre-Socratic Philosophers 1st to 3rd Week Socratic Philosophy 3rd to 4th Week Unit II: Plato: 4th to 5th Week Introduction, Theory of knowledge 5th to 7thWeek Plato: Theory of knowledge: Knowledge(episteme), and Opinion(doxa) 7th to 8th Week Plato: Theory of Forms, Soul, Idea of God Unit III: Aristotle: 8th to 10th Week Introduction, Critique of Plato’s theory of Forms Aristotle: Theory of Causation 10th to 11th Week Aristotle: Categories, God 11th to 12th Week Unit IV: St. Thomas Aquinas: 12th to 13th Week faith and reason; essence and existence; St. Thomas Aquinas: proofs for the existence of God 13th to 14th Week St. Augustine 14th to 16th Week PHIL 0301: History of Western Epistemology and Metaphysics Topic No. -

How Ancient Greek Philosophy Can Be Made Relevant to Contemporary Life James Duerlinger*

Journal of Philosophy of Life Vol.1, No.1 (March 2011):1-12 How Ancient Greek Philosophy Can Be Made Relevant to Contemporary Life James Duerlinger* Abstract In this paper, I will explain how ancient Greek philosophy can be made relevant to our lives. I do this by explaining how an instructor of a course in ancient Greek philosophy can teach Greek philosophy in a way that makes its study relevant to how the students in the course live their lives. Since this is the most likely way in which its relevance to contemporary life might be realized in practice, I explain its relevance from this perspective. I contrast the different ways in which ancient Greek philosophy is taught, and give examples of how it can be taught that calls attention to the ways in which what the Greeks said are relevant to how students live their lives. In this paper, I will explain how ancient Greek philosophy can be made relevant to contemporary life. The form in which I will explain this is by discussing how an instructor of a course in ancient Greek philosophy can teach Greek philosophy in a way that makes its study relevant to how the students in the course live their lives, since this is the most likely way in which its relevance to contemporary life might be realized in practice. One of the ways in which many instructors of courses in ancient Greek philosophy attempt to make its study relevant to the interests of their students is to teach the course from the perspective of contemporary analytic philosophy.1 This way to teach the course makes it relevant to students who have a background in contemporary analytic philosophy or wish to pursue a career as a professional philosopher or to seek a historical background to contemporary philosophy.2 A more traditional way to make the course relevant is to teach it as * Professor, Philosophy Department, University of Iowa, 11 Woodland Hts. -

Rhetorical Analysis

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS PURPOSE Almost every text makes an argument. Rhetorical analysis is the process of evaluating elements of a text and determining how those elements impact the success or failure of that argument. Often rhetorical analyses address written arguments, but visual, oral, or other kinds of “texts” can also be analyzed. RHETORICAL FEATURES – WHAT TO ANALYZE Asking the right questions about how a text is constructed will help you determine the focus of your rhetorical analysis. A good rhetorical analysis does not try to address every element of a text; discuss just those aspects with the greatest [positive or negative] impact on the text’s effectiveness. THE RHETORICAL SITUATION Remember that no text exists in a vacuum. The rhetorical situation of a text refers to the context in which it is written and read, the audience to whom it is directed, and the purpose of the writer. THE RHETORICAL APPEALS A writer makes many strategic decisions when attempting to persuade an audience. Considering the following rhetorical appeals will help you understand some of these strategies and their effect on an argument. Generally, writers should incorporate a variety of different rhetorical appeals rather than relying on only one kind. Ethos (appeal to the writer’s credibility) What is the writer’s purpose (to argue, explain, teach, defend, call to action, etc.)? Do you trust the writer? Why? Is the writer an authority on the subject? What credentials does the writer have? Does the writer address other viewpoints? How does the writer’s word choice or tone affect how you view the writer? Pathos (a ppeal to emotion or to an audience’s values or beliefs) Who is the target audience for the argument? How is the writer trying to make the audience feel (i.e., sad, happy, angry, guilty)? Is the writer making any assumptions about the background, knowledge, values, etc. -

Curriculum Vitae, April 2020

John P. F. Wynne Curriculum vitae, April 2020 Department of World Languages & Cultures, Languages & Communication Building, 255 S Central Campus Drive, Room 1400, Salt Lake City, UT, 84112. [email protected] • Office: (801)-581-8384 Major research interests. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy and religion, especially of the Hellenistic and later periods; Cicero; philosophy of religion and philosophical skepticism. Other major teaching interests. Latin and ancient Greek literature; Augustine of Hippo, early Christian thought, and late antiquity. Employment. 2018- Associate Professor of Classics Department of World Languages & Cultures, University of Utah 2014-2018 Associate Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2008-2014 Assistant Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2007-8 College Fellow, Department of Classics, Northwestern University. Education. Jan 2003 - Jan 2008 PhD in Classics, Cornell University. Dissertation: Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. Committee: Charles Brittain, Terence Irwin, Hayden Pelliccia. Lane Cooper Fellow, 2006-2007. Fall 2002 Language study in Arabic with Persian at Durham University. 2001-2 Non-degree exchange graduate student in Classics, Cornell University. 1997-2001 BA (1st Hons.) in Literae Humaniores (= Classics), Oxford University. 1 Publications (most recent first). [1] ‘Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations: a sceptical reading.’ Accepted for publication in Summer 2020 edition of Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy. [2] ‘Cicero on the soul’s sensation of itself: Tusculans 1.49-76.’ Forthcoming (proofs corrected) in Brad Inwood and James Warren (eds.), Body and Soul in Hellenistic Philosophy, the published volume from the July 2016 Symposium Hellenisticum (see below). [3] Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. -

5. Glossary of Terms

5 Glossary of Terms Here in the glossary, we have tried to be as concise as possible in defin- ing and describing terms. Our glossary of the terms is specific to our treatment of the teaching of argument in this text. This means that some terms specific to Kenneth Burke’s terministic screen appear among traditional argument terms. By no means is this a definitive or exhaus- tive list, as most rhetorical terms are applicable to teaching argument. For more complete historical and theoretical definitions of key rhetori- cal terms, interested readers might consult one of the more compre- hensive reference works, such as the Encyclopedia of Rhetoric, edited by Thomas Sloane, the Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition, edited by Theresa Enos, or the Sourcebook on Rhetoric by James Jasinski. Action vs. Motion—In A Grammar of Motives, Burke defines action as the “human body in conscious or purposive motion” (14). Action is something only human beings are capable of. A capacity to act, mean- while, is a prerequisite for moral choices. A baseball, thus, is capable of motion but not action, as it “is neither moral nor immoral, it can- not act, it can only move, or be moved” (136). For Burke, action in- volves moving toward an ideal, creating novelty along the way. The transformations effected by action are all necessarily partial, by neces- sity, due to the paradox of substance. See also: Magic, the Paradox of Substance. Agonistic/Eristical Argument—From the Greek agon, meaning con- test or conflict, and eris, meaning strife; agonistic or eristical argument represents a model of argument stressing conflict and dispute, advanc- ing one person’s perspective at the expense of others. -

Logic, Sets, and Proofs David A

Logic, Sets, and Proofs David A. Cox and Catherine C. McGeoch Amherst College 1 Logic Logical Statements. A logical statement is a mathematical statement that is either true or false. Here we denote logical statements with capital letters A; B. Logical statements be combined to form new logical statements as follows: Name Notation Conjunction A and B Disjunction A or B Negation not A :A Implication A implies B if A, then B A ) B Equivalence A if and only if B A , B Here are some examples of conjunction, disjunction and negation: x > 1 and x < 3: This is true when x is in the open interval (1; 3). x > 1 or x < 3: This is true for all real numbers x. :(x > 1): This is the same as x ≤ 1. Here are two logical statements that are true: x > 4 ) x > 2. x2 = 1 , (x = 1 or x = −1). Note that \x = 1 or x = −1" is usually written x = ±1. Converses, Contrapositives, and Tautologies. We begin with converses and contrapositives: • The converse of \A implies B" is \B implies A". • The contrapositive of \A implies B" is \:B implies :A" Thus the statement \x > 4 ) x > 2" has: • Converse: x > 2 ) x > 4. • Contrapositive: x ≤ 2 ) x ≤ 4. 1 Some logical statements are guaranteed to always be true. These are tautologies. Here are two tautologies that involve converses and contrapositives: • (A if and only if B) , ((A implies B) and (B implies A)). In other words, A and B are equivalent exactly when both A ) B and its converse are true. -

Chapter 3 – Describing Syntax and Semantics CS-4337 Organization of Programming Languages

!" # Chapter 3 – Describing Syntax and Semantics CS-4337 Organization of Programming Languages Dr. Chris Irwin Davis Email: [email protected] Phone: (972) 883-3574 Office: ECSS 4.705 Chapter 3 Topics • Introduction • The General Problem of Describing Syntax • Formal Methods of Describing Syntax • Attribute Grammars • Describing the Meanings of Programs: Dynamic Semantics 1-2 Introduction •Syntax: the form or structure of the expressions, statements, and program units •Semantics: the meaning of the expressions, statements, and program units •Syntax and semantics provide a language’s definition – Users of a language definition •Other language designers •Implementers •Programmers (the users of the language) 1-3 The General Problem of Describing Syntax: Terminology •A sentence is a string of characters over some alphabet •A language is a set of sentences •A lexeme is the lowest level syntactic unit of a language (e.g., *, sum, begin) •A token is a category of lexemes (e.g., identifier) 1-4 Example: Lexemes and Tokens index = 2 * count + 17 Lexemes Tokens index identifier = equal_sign 2 int_literal * mult_op count identifier + plus_op 17 int_literal ; semicolon Formal Definition of Languages • Recognizers – A recognition device reads input strings over the alphabet of the language and decides whether the input strings belong to the language – Example: syntax analysis part of a compiler - Detailed discussion of syntax analysis appears in Chapter 4 • Generators – A device that generates sentences of a language – One can determine if the syntax of a particular sentence is syntactically correct by comparing it to the structure of the generator 1-5 Formal Methods of Describing Syntax •Formal language-generation mechanisms, usually called grammars, are commonly used to describe the syntax of programming languages. -

Topics in Philosophical Logic

Topics in Philosophical Logic The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Litland, Jon. 2012. Topics in Philosophical Logic. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9527318 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © Jon Litland All rights reserved. Warren Goldfarb Jon Litland Topics in Philosophical Logic Abstract In “Proof-Theoretic Justification of Logic”, building on work by Dummett and Prawitz, I show how to construct use-based meaning-theories for the logical constants. The assertability-conditional meaning-theory takes the meaning of the logical constants to be given by their introduction rules; the consequence-conditional meaning-theory takes the meaning of the log- ical constants to be given by their elimination rules. I then consider the question: given a set of introduction (elimination) rules , what are the R strongest elimination (introduction) rules that are validated by an assertabil- ity (consequence) conditional meaning-theory based on ? I prove that the R intuitionistic introduction (elimination) rules are the strongest rules that are validated by the intuitionistic elimination (introduction) rules. I then prove that intuitionistic logic is the strongest logic that can be given either an assertability-conditional or consequence-conditional meaning-theory. In “Grounding Grounding” I discuss the notion of grounding. My discus- sion revolves around the problem of iterated grounding-claims. -

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) • His father, a professor of Philosophy, died when he was small, and he was brought up by his mother. • He learnt Latin at school in Leipzig, but taught himself much more and also taught himself some Greek, possibly because he wanted to read his father’s books. • He studied law and logic at Leipzig University from the age of fourteen – which was not exceptionally young for that time. • His Ph D thesis “De Arte Combinatoria” was completed in 1666 at the University of Altdorf. He was offered a chair there but turned it down. • He then met, and worked for, Baron von Boineburg (at one stage prime minister in the government of Mainz), as a secretary, librarian and lawyer – and was also a personal friend. • Over the years he earned his living mainly as a lawyer and diplomat, working at different times for the states of Mainz, Hanover and Brandenburg. • But he is famous as a mathematician and philosopher. • By his own account, his interest in mathematics developed quite late. • An early interest was mechanics. – He was interested in the works of Huygens and Wren on collisions. – He published Hypothesis Physica Nova in 1671. The hypothesis was that motion depends on the action of a spirit ( a hypothesis shared by Kepler– but not Newton). – At this stage he was already communicating with scientists in London and in Paris. (Over his life he had around 600 scientific correspondents, all over the world.) – He met Huygens in Paris in 1672, while on a political mission, and started working with him.