Heritage Houses of County Cork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Day Driftwood Castles and Kingdoms Tour Highlights

7 day driftwood castles and kingdoms tour Sample Itinerary We are proud that no two Driftwood tours are the same. Your own preferences, your guide and the famous Irish weather mean that the following itinerary should be understood as a framework only. Accommodation options are fixed. We then base each tour around the list of daily stops below. Your guide will discuss options with you throughout your tour and plan accordingly. If there is something that you particularly want to do or see on your tour, mention it to your guide. We will do our best to match your choice with the preferences of your Vagabond group. Our Sales and Reservation team can advise you further on any aspect of the tour. Email Megan directly at [email protected] highlights VISIT IRELAND’S GREAT CASTLES HOUSES AND GARDENS ● Live like lords and ladies for one unforgettable night at Ballyseede Castle Hotel ● Kiss the famous Blarney Stone at Blarney Castle and Gardens ● Tour 18th Century Bantry House and Gardens ● See elegant 19th Century Muckross House Gardens ● Be dwarfed by one of Ireland’s largest medieval castles at Cahir REVEL AT SOME OF EUROPE’S VERY BEST SCENERY: ● Elevate your mood along the wild and rugged Atlantic Ocean coastline ● Feel the magic on the world famous Ring of Kerry ● See Ireland’s highest mountain range, The Macgillycuddy Reeks ● Behold the lunar limestone landscape of The Burren ● Watch waves crash along the spectacular Loop Head drive RELISH SOME OF IRELAND’S MOST WORTHWHILE TOURIST DESTINATIONS: ● Stand in awe at the towering Cliffs of Moher -

Copyrighted Material

18_121726-bindex.qxp 4/17/09 2:59 PM Page 486 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Ardnagashel Estate, 171 Bank of Ireland The Ards Peninsula, 420 Dublin, 48–49 Abbey (Dublin), 74 Arigna Mining Experience, Galway, 271 Abbeyfield Equestrian and 305–306 Bantry, 227–229 Outdoor Activity Centre Armagh City, 391–394 Bantry House and Garden, 229 (Kildare), 106 Armagh Observatory, 394 Barna Golf Club, 272 Accommodations. See also Armagh Planetarium, 394 Barracka Books & CAZ Worker’s Accommodations Index Armagh’s Public Library, 391 Co-op (Cork City), 209–210 saving money on, 472–476 Ar mBréacha-The House of Beach Bar (Aughris), 333 Achill Archaeological Field Storytelling (Wexford), Beaghmore Stone Circles, 446 School, 323 128–129 The Beara Peninsula, 230–231 Achill Island, 320, 321–323 The arts, 8–9 Beara Way, 230 Adare, 255–256 Ashdoonan Falls, 351 Beech Hedge Maze, 94 Adrigole Arts, 231 Ashford Castle (Cong), 312–313 Belfast, 359–395 Aer Lingus, 15 Ashford House, 97 accommodations, 362–368 Agadhoe, 185 A Store is Born (Dublin), 72 active pursuits, 384 Aillwee Cave, 248 Athlone, 293–299 brief description of, 4 Aircoach, 16 Athlone Castle, 296 gay and lesbian scene, 390 Airfield Trust (Dublin), 62 Athy, 102–104 getting around, 362 Air travel, 461–468 Athy Heritage Centre, 104 history of, 360–361 Albert Memorial Clock Tower Atlantic Coast Holiday Homes layout of, 361 (Belfast), 377 (Westport), 314 nightlife, 386–390 Allihies, 230 Aughnanure Castle (near the other side of, 381–384 All That Glitters (Thomastown), -

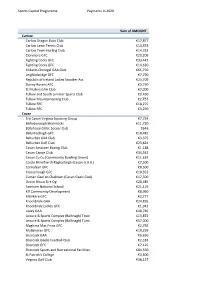

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club €17,877 Carlow Lawn Tennis Club €14,353 Carlow Town Hurling Club €14,332 Clonmore GFC €23,209 Fighting Cocks GFC €33,442 Fighting Cocks GFC €14,620 Kildavin Clonegal GAA Club €61,750 Leighlinbridge GFC €7,790 Republic of Ireland Ladies Snooker Ass €23,709 Slaney Rovers AFC €3,750 St Mullins GAA Club €7,000 Tullow and South Leinster Sports Club €9,430 Tullow Mountaineering Club €2,757 Tullow RFC €18,275 Tullow RFC €3,250 Cavan 3rd Cavan Virginia Scouting Group €7,754 Bailieborough Shamrocks €11,720 Ballyhaise Celtic Soccer Club €646 Ballymachugh GFC €10,481 Belturbet GAA Club €3,375 Belturbet Golf Club €23,824 Cavan Amatuer Boxing Club €1,188 Cavan Canoe Club €34,542 Cavan Co Co (Community Bowling Green) €11,624 Coiste Bhreifne Uí Raghaillaigh (Cavan G.A.A.) €7,500 Cornafean GFC €8,500 Crosserlough GFC €10,352 Cuman Gael an Chabhain (Cavan Gaels GAA) €17,500 Droim Dhuin Eire Og €20,485 Farnham National School €21,119 Kill Community Development €8,960 Killinkere GFC €2,777 Knockbride GAA €24,835 Knockbride Ladies GFC €1,942 Lavey GAA €48,785 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Trust €13,872 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Turst €57,000 Maghera Mac Finns GFC €2,792 Mullahoran GFC €10,259 Shercock GAA €6,650 Shercock Gaelic Football Club €2,183 Shercock GFC €7,125 Shercock Sports and Recreational Facilities €84,550 St Patrick's College €3,500 Virginia Golf Club €38,127 Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Virginia Kayak Club €9,633 Cavan Castlerahan -

June 2020 €2.50 W Flowers for All Occasions W Individually W

THE CHURCH OF IRELAND United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE Technology enables us ‘to be together while apart’ - Rev Kingsley Sutton celebrates his 50th birthday with some of his colleagues on Zoom June 2020 €2.50 w flowers for all occasions w Individually w . e Designed Bouquets l e g a & Arrangements n c e f lo Callsave: ri st 1850 369369 s. co m The European Federation of Interior Landscape Groups •Fresh & w w Artificial Plant Displays w .f lo •Offices • Hotels ra ld •Restaurants • Showrooms e c o r lt •Maintenance Service d . c •Purchase or Rental terms o m Tel: (021) 429 2944 bringing interiors alive 16556 DOUGLAS ROAD, CORK United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE June 2020 Volume XLV - No.6 The Bishop writes… Dear Friends, Another month has passed and with it have come more changes, challenges and tragedies. On behalf of us all I extend sympathy, not only to the loved ones of all those who have died of COVID-19, but also to everyone who has been bereaved during this pandemic. Not being able to give loved ones the funeral we would really want to give them is one of the most heart-breaking aspects of the current times. Much in my prayers and yours, have been those who are ill with COVID-19 and all others whose other illnesses have been compounded by the strictures of these times. In a different way, Leaving Certificate students and their families have been much in my thoughts and prayers. -

Cork City Development Plan

Cork City Development Plan Comhairle Cathrach Chorcaí Cork City Council 2015 - 2021 Environmental Assessments Contents • Part 1: Non-Technical Summary SEA Environmental Report 3 • Part 2: SEA Environmental Report 37 SEA Appendices 191 • Part 3: Strategic Flood Risk Assessment (SFRA) 205 SFRA Appendices 249 • Part 4: Screening for Appropriate Assessment 267 Draft Cork City Development Plan 2015-2021 1 Volume One: Written Statement Copyright Cork City Council 2014 – all rights reserved. Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi. Licence number 2014/05/CCMA/CorkCityCouncil © Ordnance Survey Ireland. All rights reserved. 2 Draft Cork City Development Plan 2015-2021 Part 1: SEA Non-Technical Summary 1 part 1 Non-Technical Summary Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Contents • Introduction 5 • Context 6 • Baseline Environment 6 • Strategic Environmental Protection Objectives 15 • Alternative Scenarios 21 • Evaluation of Alternative Scenarios 22 • Evaluation of the Draft Plan 26 • Monitoring the Plan 27 Draft Cork City Development Plan 2015-2021 3 1 Volume Four: Environmental Reports 4 Draft Cork City Development Plan 2015-2021 Part 1: SEA Non-Technical Summary 1 PART 1 SEA NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY 1. Introduction Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is the formal, systematic assessment of the likely effects on implementing a plan or programme before a decision is made to adopt the plan or programme. This Report describes the assessment of the likely significant effects on the environment if the draft City Development Plan is implemented. It is a mandatory requirement to undertake a SEA of the City Development Plan, under the Planning and Development (Strategic Environmental Assessment) Regulations, 2004 (as amended). SEA began with the SEA Directive, namely, Directive 2001/42/EC Assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment. -

A Provisional Inventory of Ancient and Long-Established Woodland in Ireland

A provisional inventory of ancient and long‐established woodland in Ireland Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 46 A provisional inventory of ancient and long‐ established woodland in Ireland Philip M. Perrin and Orla H. Daly Botanical, Environmental & Conservation Consultants Ltd. 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street, Dublin 2. Citation: Perrin, P.M. & Daly, O.H. (2010) A provisional inventory of ancient and long‐established woodland in Ireland. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 46. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland. Cover photograph: St. Gobnet’s Wood, Co. Cork © F. H. O’Neill The NPWS Project Officer for this report was: Dr John Cross; [email protected] Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editors: N. Kingston & F. Marnell © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2010 ISSN 1393 – 6670 Ancient and long‐established woodland inventory ________________________________________ CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 3 Rationale 3 Previous research into ancient Irish woodland 3 The value of ancient woodland 4 Vascular plants as ancient woodland indicators 5 Definitions of ancient and long‐established woodland 5 Aims of the project 6 DESK‐BASED RESEARCH 7 Overview 7 Digitisation of ancient and long‐established woodland 7 Historic maps and documentary sources 11 Interpretation of historical sources 19 Collation of previous Irish ancient woodland studies 20 Supplementary research 22 Summary of desk‐based research 26 FIELD‐BASED RESEARCH 27 Overview 27 Selection of sites -

United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE

THE CHURCH OF IRELAND United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE A Symbol of ‘Hope’ May 2020 €2.50 w flowers for all occasions w Individually w . e Designed Bouquets l e g a & Arrangements n c e f lo Callsave: ri st 1850 369369 s. co m The European Federation of Interior Landscape Groups •Fresh & w w Artificial Plant Displays w .f lo •Offices • Hotels ra ld •Restaurants • Showrooms e c o r lt •Maintenance Service d . c •Purchase or Rental terms o m Tel: (021) 429 2944 bringing interiors alive 16556 DOUGLAS ROAD, CORK United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE May 2020 Volume XLV - No.5 The Bishop writes… Dear Friends, Last month’s letter which I published online was written the day after An Taoiseach announced that gatherings were to be limited to 100 people indoors and to 500 people outdoors. Since then we have had a whirlwind of change. Many have faced disappointments and great challenges. Still others find that the normality of their lives has been upended. For too many, illness they have already been living with has been complicated, and great numbers have struggled with or are suffering from COVID-19. We have not been able to give loved ones who have died in these times the funerals we would like to have arranged for them. Those working in what have been classed as ‘essential services’, especially those in all branches of healthcare, are working in a new normality that is at the limit of human endurance. Most of us are being asked to make our contribution by heeding the message: ‘Stay at home’ These are traumatic times for everyone. -

Inspector's Report PL04.248400

Inspector’s Report PL04.248400 Development Construction of a solar farm with photovoltaic panels on mounted frames with two transformer stations, one delivery station, fencing, CCTV and associated site works. Location Ballinvarrig East, Deerpark, Castlelyons. Co Cork. Planning Authority Cork Co Council. Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 16/5414. Applicant(s) Amarenco Solar Ballinvarrig Ltd. Type of Application Permission. Planning Authority Decision To Grant Permission. Type of Appeal Third Party Appellant(s) Castlelyons Development. Observer(s) None. Date of Site Inspection August 15th, 017. Inspector Breda Gannon. PL04.248400 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 44 1.0 Site Location and Description 1.1. The site lies between the villages of Rathcormack and Castlelyons, to the south of Fermoy in Co Cork. It is located on the south side of the local road (L1520-11) connecting the two villages. The site is accessed by a farm track, located between two dwelling houses. The track extends southwards, bounded by trees/hedgerow on both sides, towards a large agricultural field devoted to tillage. To the east side of the field there is an area of woodland with agricultural land extending out to the west. The River Bride runs a short distance to the south of the site. 1.2. The area is predominantly agricultural, in a gently rolling rural topography, rising significantly towards the R628 to the south. The pattern of development is dispersed, comprising isolated rural holdings, with a significant concentration of single dwellings located in ribbon form along the local road. 2.0 Proposed Development 2.1. The proposal is to develop a 5 MW solar farm comprising c. -

Sea Environmental Report the Three

SEA ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT FOR THE THREE PENINSULAS WEST CORK AND KERRY DRAFT VISITOR EXPERIENCE DEVELOPMENT PLAN for: Fáilte Ireland 88-95 Amiens Street Dublin 1 by: CAAS Ltd. 1st Floor 24-26 Ormond Quay Upper Dublin 7 AUGUST 2020 SEA Environmental Report for The Three Peninsulas West Cork and Kerry Draft Visitor Experience Development Plan Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................v Glossary ..................................................................................................................vii SEA Introduction and Background ..................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction and Terms of Reference ........................................................................... 1 1.2 SEA Definition ............................................................................................................ 1 1.3 SEA Directive and its transposition into Irish Law .......................................................... 1 1.4 Implications for the Plan ............................................................................................. 1 The Draft Plan .................................................................................... 3 2.1 Overview ................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Relationship with other relevant Plans and Programmes ................................................ 4 SEA Methodology .............................................................................. -

Cork County Grit Locations

Cork County Grit Locations North Cork Engineer's Area Location Charleville Charleville Public Car Park beside rear entrance to Library Long’s Cross, Newtownshandrum Turnpike Doneraile (Across from Park entrance) Fermoy Ballynoe GAA pitch, Fermoy Glengoura Church, Ballynoe The Bottlebank, Watergrasshill Mill Island Carpark on O’Neill Crowley Quay RC Church car park, Caslelyons The Bottlebank, Rathcormac Forestry Entrance at Castleblagh, Ballyhooley Picnic Site at Cork Road, Fermoy beyond former FCI factory Killavullen Cemetery entrance Forestry Entrance at Ballynageehy, Cork Road, Killavullen Mallow Rahan old dump, Mallow Annaleentha Church gate Community Centre, Bweeng At Old Creamery Ballyclough At bottom of Cecilstown village Gates of Council Depot, New Street, Buttevant Across from Lisgriffin Church Ballygrady Cross Liscarroll-Kilbrin Road Forge Cross on Liscarroll to Buttevant Road Liscarroll Community Centre Car Park Millstreet Glantane Cross, Knocknagree Kiskeam Graveyard entrance Kerryman’s Table, Kilcorney opposite Keim Quarry, Millstreet Crohig’s Cross, Ballydaly Adjacent to New Housing Estate at Laharn Boherbue Knocknagree O Learys Yard Boherbue Road, Fermoyle Ball Alley, Banteer Lyre Village Ballydesmond Church Rd, Opposite Council Estate Mitchelstown Araglin Cemetery entrance Mountain Barracks Cross, Araglin Ballygiblin GAA Pitch 1 Engineer's Area Location Ballyarthur Cross Roads, Mitchelstown Graigue Cross Roads, Kildorrery Vacant Galtee Factory entrance, Ballinwillin, Mitchelstown Knockanevin Church car park Glanworth Cemetery -

Heritage Bridges of County Cork

Heritage Bridges of County Cork Published by Heritage Unit of Cork County Council 2013 Phone: 021 4276891 - Email: [email protected]. ©Heritage Unit of Cork County Council 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the written permission of the publisher. Paperback - ISBN No. 978-0-9525869-6-8 Hardback - ISBN No. 978-0-9525869-7-5 Neither the authors nor the publishers (Heritage Unit of Cork County Council) are responsible for the consequences of the use of advice offered in this document by anyone to whom the document is supplied. Nor are they responsible for any errors, omissions or discrepancies in the information provided. Printed and bound in Ireland by Carraig Print inc. Litho Press Carrigtwohill, Co. Cork, Ireland. Tel: 021 4883458 List of Contributors: (those who provided specific information or photographs for use in this publication (in addition to Tobar Archaeology (Miriam Carroll and Annette Quinn), Blue Brick Heritage (Dr. Elena Turk) , Lisa Levis Carey, Síle O‟ Neill and Cork County Council personnel). Christy Roche Councillor Aindrias Moynihan Councillor Frank O‟ Flynn Diarmuid Kingston Donie O‟ Sullivan Doug Lucey Eilís Ní Bhríain Enda O‟Flaherty Jerry Larkin Jim Larner John Hurley Karen Moffat Lilian Sheehan Lynne Curran Nelligan Mary Crowley Max McCarthy Michael O‟ Connell Rose Power Sue Hill Ted and Nuala Nelligan Teddy O‟ Brien Thomas F. Ryan Photographs: As individually stated throughout this publication Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Licence number 2013/06/CCMA/CorkCountyCouncil Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. -

Cork County Council Planning Applications

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 19/10/2019 TO 25/10/2019 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: West Cork, Bandon/Kinsale, Blarney/Macroom, Ballincollig/Carrigaline, Kanturk/Mallow, Fermoy, Cobh, East Cork FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE RECEIVED DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS RECD. PROT STRU IPC LIC. WASTE LIC. 19/00670 John and Eileen Twomey Permission for 21/10/2019 Permission for retention of extensions and alterations, including No No No No Retention attic space to single storey dwelling and a detached domestic garage Ardnageehy More Bantry Co. Cork 19/00671 Jan Willem Findlater Permission, 21/10/2019 Alterations to elevations of dwelling and conversion of attached No No No No Permission for garage to domestic workshop. Permission is also sought for Retention alterations to elevations of dwelling. South Square Lower Lamb Street Clonakilty Co. Cork 19/00672 Maria McSweeney, Darren Bulman Permission 22/10/2019 Construction of ext ensions, including the construction of an No No No No attached ancillary dwelling unit (for use as family accommodation / granny flat), elevational changes, demolitions, internal refurbishments to facilitate a family home upgrade to an existing dwelling, landscaping and all associated site works Teadies Lower Enniskean Co.