Diegetic Short Circuits: Metalepsis in Animation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ji Woon Kim Rhetoric 105 Professor Mary Hays 15 March 2016 Loss Of

Ji Woon Kim Rhetoric 105 Professor Mary Hays 15 March 2016 Loss of Original Intention: Budget for Art or Art for Money? A Review of Alter Ego by Laurence Green, mainly focusing on the movie Ryan by Chris Landreth *Blue-Revised As the title of the movie suggests, it is all about Ryan, who was a notable animator and an Oscar nominee back in 60’s and early 70’s, contributing greatly to moving arts. This movie was made by Chris Landreth, who got interested in him after he got to know that a big figure in animation industry was now living in a street in Montreal. Interestingly, the movie is based on an actual interview, and it is dubbed within the animation. This actually made the movie realistic, as we can hear real voices of the two animators. However, the notable point of the movie is that all characters in the animation have distorted looks. The reason is because Chris wanted to show psychological status through physical attributes. Chris uses surreal CG imagery to show the psychology of each character from his technique called “Psychorealism”(Chris Landreth). The use of “psychedelic CG animation” elucidated the life and unstable mind of the legendary animator, Ryan Larkin. In the movie, their relationship was beyond one-way sympathy toward the wrecked life of Chris’s hero, Ryan. Especially, it shows through the embodiment of “colorful chains” around both of them after the success in their career. When Ryan achieved the climax of his career with “Walking” and “Street Musique,” colorful chains wraps around his face. -

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Fraternite! Eqalite!

VOL. 119 - NO. 3 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, JANUARY 16, 2015 $.35 A COPY Liberte! Fraternite! Eqalite! by Sal Giarratani This past Saturday, a large How can we defeat an en- crowd gathered on the emy if we won’t even prop- Boston Common standing in erly identify who that enemy solidarity with millions of is? Even the new Presi- people in Paris’ Place de la dent of Egypt Abdel-Fattah Republique against Radical el-Sissi has courageously Islamic acts of terror that spoken for the need for a killed 17 people last week. Revolution in Islam and for Some 40 world leaders countering those who mis- joined arms together in sup- use the religion of Muslims. port of France and against On second thought, per- those seeking civilization haps Obama didn’t belong jihad. in that recent gathering in Many marched together in Paris since the world needed support of those values of to see leaders linking arms modern civilization under with one another. attack today. It was a march We insulted not only for liberty. It was a march for the French of 2015, we in- all of us. It was also a march sulted the bond between against those using reli- our nations built up since gious fanaticism and killing the days of the American innocents in the name of White House, it was a dumb send Vice President Joe was a deliberate move not to Revolution. their God. mistake that America went Biden or Secretary of State link the United States of We must not be afraid to Why wasn’t President AWOL at this world-wide John F. -

American WWII Propaganda Cartoons

Name _____________________________________ Date ________________________ Period ______ American WWII Propaganda Cartoons “Blitz Wolf” – A cartoon produced in 1942 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Short Subject Cartoon. The plot is a parody of the Three Little Pigs, told from a WWII anti-German propaganda perspective. As you watch the cartoon, answer the following questions: Who do the Three Little Pigs represent? Who does the Wolf represent? What does this cartoon say about America’s view of Germany and Hitler? “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap” - A 1942 one-reel animated cartoon short subject released by Paramount Pictures. It is one of the best-known World War II propaganda cartoons. The cartoon gets its title from a novelty song written by James Cavanaugh, John Redmond and Nat Simon. As you watch the cartoon, answer the following questions: Who does Popeye represent? How are the Japanese portrayed? What does this cartoon say about America’s view of Japan and its people? Using complete sentences, answer the following questions about the use of animated cartoons for anti- war propaganda. 1. Is the use of animation and humor appropriate for depicting the serious nature of war? Use at least 2 specific examples to explain your opinion. 2. The U.S. has been fighting the War on Terror for over a decade. If such propaganda cartoons were made today featuring Iraqis, Afghans, or others targeted in the War on Terror, would they be accepted? Would they be considered offensive? Use at least 2 specific examples to explain your opinion. -

Animation:Then,Now,Next

Fall 2020 FYI, section 093 is a 2nd half of the semester course. If you wish to enroll in the full-semester version please email instructor FILM1600 : Then|Now|Next [email protected] for permission code. (August 17,2020) What you need to know! Designed to be online (asynchronous – anytime during the week) since 2016. It is not a zoom/IVC adaptation because of COVID. The course incorporates extensive visual media that make up the majority of the course content (no required book to purchase). It is now 99% Closed Captioned (spring 2020). Updated each semester with newest advances in the field. This course is 8 weeks long, which means things move a bit faster to fit everything in but is very manageable with good organization. What is different about this course… this is not a history course but reveals the people, processes and future changes in how animation is used in digital media. The content of the course draws directly from the professor’s experience and insights working at Disney Feature Animation and Electronic Arts (games). Weekly Modules are structured to emulate regular in-person classes. The modules contain each week's opening animations, lectures, readings, and quizzes. You can access the material several weeks before due dates. Course Content Animation techniques have evolved from simple cartoon drawings to 3D VFX. Today this evolution continues as it is Link to Sample Lecture Class rapidly being integrated into XR. From Animation's beginnings, (2 lectures per week) each new technological innovation extended the creative possibilities for storytelling (e.g. -

Elenco Film Dal 2015 Al 2020

7 Minuti Regia: Michele Placido Cast: Cristiana Capotondi, Violante Placido, Ambra Angiolini, Ottavia Piccolo Genere: Drammatico Distributore: Koch Media Srl Uscita: 03 novembre 2016 7 Sconosciuti Al El Royale Regia: Drew Goddard Cast: Chris Hemsworth, Dakota Johnson, Jeff Bridges, Nick Offerman, Cailee Spaeny Genere: Thriller Distributore: 20th Century Fox Uscita: 25 ottobre 2018 7 Uomini A Mollo Regia: Gilles Lellouche Cast: Mathieu Amalric, Guillaume Canet, Benoît Poelvoorde, Jean-hugues Anglade Genere: Commedia Distributore: Eagle Pictures Uscita: 20 dicembre 2018 '71 Regia: Yann Demange Cast: Jack O'connell, Sam Reid Genere: Thriller Distributore: Good Films Srl Uscita: 09 luglio 2015 77 Giorni Regia: Hantang Zhao Cast: Hantang Zhao, Yiyan Jiang Genere: Avventura Distributore: Mescalito Uscita: 15 maggio 2018 87 Ore Regia: Costanza Quatriglio Genere: Documentario Distributore: Cineama Uscita: 19 novembre 2015 A Beautiful Day Regia: Lynne Ramsay Cast: Joaquin Phoenix, Alessandro Nivola, Alex Manette, John Doman, Judith Roberts Genere: Thriller Distributore: Europictures Srl Uscita: 01 maggio 2018 A Bigger Splash Regia: Luca Guadagnino Cast: Ralph Fiennes, Dakota Johnson Genere: Drammatico Distributore: Lucky Red Uscita: 26 novembre 2015 3 Generations - Una Famiglia Quasi Perfetta Regia: Gaby Dellal Cast: Elle Fanning, Naomi Watts, Susan Sarandon, Tate Donovan, Maria Dizzia Genere: Commedia Distributore: Videa S.p.a. Uscita: 24 novembre 2016 40 Sono I Nuovi 20 Regia: Hallie Meyers-shyer Cast: Reese Witherspoon, Michael Sheen, Candice -

Animating Race the Production and Ascription of Asian-Ness in the Animation of Avatar: the Last Airbender and the Legend of Korra

Animating Race The Production and Ascription of Asian-ness in the Animation of Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra Francis M. Agnoli Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies April 2020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 2 Abstract How and by what means is race ascribed to an animated body? My thesis addresses this question by reconstructing the production narratives around the Nickelodeon television series Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005-08) and its sequel The Legend of Korra (2012-14). Through original and preexisting interviews, I determine how the ascription of race occurs at every stage of production. To do so, I triangulate theories related to race as a social construct, using a definition composed by sociologists Matthew Desmond and Mustafa Emirbayer; re-presentations of the body in animation, drawing upon art historian Nicholas Mirzoeff’s concept of the bodyscape; and the cinematic voice as described by film scholars Rick Altman, Mary Ann Doane, Michel Chion, and Gianluca Sergi. Even production processes not directly related to character design, animation, or performance contribute to the ascription of race. Therefore, this thesis also references writings on culture, such as those on cultural appropriation, cultural flow/traffic, and transculturation; fantasy, an impulse to break away from mimesis; and realist animation conventions, which relates to Paul Wells’ concept of hyper-realism. -

Perceptual Evaluation of Cartoon Physics: Accuracy, Attention, Appeal

Perceptual Evaluation of Cartoon Physics: Accuracy, Attention, Appeal Marcos Garcia∗ John Dingliana† Carol O’Sullivan‡ Graphics Vision and Visualisation Group, Trinity College Dublin Abstract deformations to real-time interactive physics simulations e.g. Cel Damage by Pseudo Interactive R and Electronic Arts R . A num- People have been using stylistic methods in classical animation for ber of papers have been published on simulating cartoon physics many years and such methods have also been recently applied in 3D using a range of different approaches from simple geometrical de- Computer Graphics. We have developed a method to apply squash formations to complex physically based models of elasticity. In this and stretch cartoon stylisations to physically based simulations in paper we present the results of a number of experiments that were real-time. In this paper, we present a perceptual evaluation of this performed to address the question of whether and to what degree approach in a series of experiments. Our hypotheses were: that styl- stylisation contributes to the quality of a real-time interactive simu- ised motion would improve user Accuracy (trajectory prediction); lation. that user Attention would be drawn more to objects with cartoon physics; and that animations with cartoon physics would have more 1.1 Contributions Appeal. In a task that required users to accurately predict the tra- jectories of bouncing objects with a range of elasticities and vary- Our main contribution in this paper is to validate some well known ing degrees of information, we found that stylisation significantly assumptions that stylised behaviour has the potential to signifi- improved user accuracy, especially for high elasticities and low in- cantly affect a user’s perception and response to a scene. -

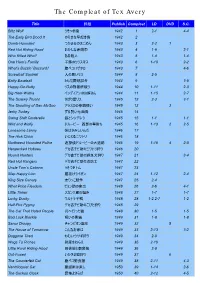

The Compleat of Tex Avery

The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C. Blitz Wolf うそつき狼 1942 1 2-1 4-4 The Early Bird Dood It のろまな早起き鳥 1942 2 Dumb-Hounded つかまるのはごめん 1943 3 2-2 1 Red Hot Riding Hood おかしな赤頭巾 1943 4 1-9 2-1 Who Killed Who? ある殺人 1943 5 1-4 1-4 One Ham’s Family 子豚のクリスマス 1943 6 1-10 2-2 What’s Buzzin’ Buzzard? 腹ペコハゲタカ 1943 7 4-6 Screwball Squirrel 人の悪いリス 1944 8 2-5 Batty Baseball とんだ野球試合 1944 9 3-5 Happy-Go-Nutty リスの刑務所破り 1944 10 1-11 2-3 Big Heel-Watha インディアンのお婿さん 1944 11 1-15 2-7 The Screwy Truant さぼり屋リス 1945 12 2-3 3-1 The Shooting of Dan McGoo アラスカの拳銃使い 1945 13 3 Jerky Turkey ずる賢い七面鳥 1945 14 Swing Shift Cinderella 狼とシンデレラ 1945 15 1-1 1-1 Wild and Wolfy ドルーピー 西部の早射ち 1945 16 1-13 2 2-5 Lonesome Lenny 僕はさみしいんだ 1946 17 The Hick Chick いじわるニワトリ 1946 18 Northwest Hounded Police 迷探偵ドルーピーの大追跡 1946 19 1-16 4 2-8 Henpecked Hoboes デカ吉チビ助のニワトリ狩り 1946 20 Hound Hunters デカ吉チビ助の野良犬狩り 1947 21 3-4 Red Hot Rangers デカ吉チビ助の消防士 1947 22 Uncle Tom’s Cabana うそつきトム 1947 23 Slap Happy Lion 腰抜けライオン 1947 24 1-12 2-4 King Size Canary 太りっこ競争 1947 25 2-4 What Price Fleadom ピョン助の家出 1948 26 2-6 4-1 Little Tinker スカンク君の悩み 1948 27 1-7 1-7 Lucky Ducky ウルトラ子鴨 1948 28 1-2 2-7 1-2 Half-Pint Pygmy デカ吉チビ助のこびと狩り 1948 29 The Cat That Hated People 月へ行った猫 1948 30 1-5 1-5 Bad Luck Blackie 呪いの黒猫 1949 31 1-8 1-8 Senor Droopy チャンピオン誕生 1949 32 5 The House of Tomorrow こんなお家は 1949 33 2-13 3-2 Doggone Tired ねむいウサギ狩り 1949 34 2-9 Wags To Riches 財産をねらえ 1949 35 2-10 Little Rural Riding Hood 田舎狼と都会狼 1949 36 2-8 Out-Foxed いかさま狐狩り 1949 37 6 The Counterfeit Cat 腹ペコ野良猫 1949 38 2-11 4-3 Ventriloquist Cat 腹話術は楽し 1950 39 1-14 2-6 The Cuckoo Clock 恐怖よさらば 1950 40 2-12 4-5 The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C. -

King Kong Went Through Animation

2 April 2008 designed a lot of the action sequences in the Oscar winner film. It was again not a simple process since there were a lot of conflicts of inteest on how to achieve the creative, hence we talks on the making of created an animated character. The footage of actual Guerrilla moments were taken from various zoos to perfect the facial system. Every motion capture shot in King Kong went through animation. Hence the King Kong MoCap has a very crucial role to play. The climax scene of the film, Christian Rivers joins a where King Kong dies, was well appreciated from all long list of illustrious visitors quarters of the industry and to Chennai based Animation wondered how the shot was and Visual Effects College - approached. It was a simple Image College of Arts, but a detailed approach when Animation & Technology we made the light in the pupil (ICAT). ICAT which offers of the eyes of King Kong Degree and Post Graduate diffused in other words we programs in Animation, made the audience to believe Visual Effects, Game Design by creating the dryness on the and Game programming has eyes to express it was dead." been bringing outstanding members from the Academic Apart from the character, and Professional segment to another amazing visual effects share their expertise with its shot in King Kong was the students. creation of New York City in 1933. A lot of research was Christian Rivers is an done in this regard, with Academy Award and BAFTA Seminar by "King Kong" maker Christian Rivers archival photographs being procured and winning New Zealand visual effects art many debates over the look of the creating buildings which were present only director and filmmaker. -

Commercials Issueissue

May 1997 • MAGAZINE • Vol. 2 No. 2 CommercialsCommercials IssueIssue Profiles of: Acme Filmworks Blue Sky Studios PGA Karl Cohen on (Colossal)Õs Life After Chapter 11 Gunnar Str¿mÕs Fumes From The Fjords An Interview With AardmanÕs Peter Lord Table of Contents 3 Words From the Publisher A few changes 'round here. 5 Editor’s Notebook 6 Letters to the Editor QAS responds to the ASIFA Canada/Ottawa Festival discussion. 9 Acme Filmworks:The Independent's Commercial Studio Marcy Gardner explores the vision and diverse talents of this unique collective production company. 13 (Colossal) Pictures Proves There is Life After Chapter 11 Karl Cohen chronicles the saga of San Francisco's (Colossal) Pictures. 18 Ray Tracing With Blue Sky Studios Susan Ohmer profiles one of the leading edge computer animation studios working in the U.S. 21 Fumes From the Fjords Gunnar Strøm investigates the history behind pre-WWII Norwegian animated cigarette commercials. 25 The PGA Connection Gene Walz offers a look back at Canadian commercial studio Phillips, Gutkin and Associates. 28 Making the Cel:Women in Commercials Bonita Versh profiles some of the commercial industry's leading female animation directors. 31 An Interview With Peter Lord Wendy Jackson talks with co-founder and award winning director of Aardman Animation Studio. Festivals, Events: 1997 37 Cartoons on the Bay Giannalberto Bendazzi reports on the second annual gathering in Amalfi. 40 The World Animation Celebration The return of Los Angeles' only animation festival was bigger than ever. 43 The Hong Kong Film Festival Gigi Hu screens animation in Hong Kong on the dawn of a new era.