Biodiversity Action Plan for Richmond 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Summary Report

Report by Rocket Science for The Barnes Fund This report draws on a wide range of data and on benefitted enormously from their input. Second, the experiences of a diverse sample of local we are grateful to 41 representatives from local residents to tell the story of need within our organisations who came together in focus groups community. The Barnes Fund concluded in late to discuss need in Barnes; to a number of others 2019 that we would like to commission such a who shared their views separately; to the 12 report in 2020, our 50th anniversary year, both to residents who took on the challenge of being inform our own grant making programme and as a trained as peer researchers; and to the 110 community resource. In the event the work was residents who agreed to be interviewed by them. carried out at a time when experience of Covid-19 The report could not have been written without and lockdown had sharpened many residents’ sense their willingness to provide frank feedback, of both ‘community’ and ‘need’ and there was much thoughts and ideas. And finally, we are grateful to that was being learned. At the same time, we have Rocket Science, who were chosen by the Steering been keen to take a longer-term perspective – both Group based on their expertise and relevant backwards in terms of understanding what pre- experience to carry out the research on our behalf, existing data tells us about ourselves and forwards who rose to the challenge of doing everything in terms of understanding hopes, concerns and remotely (online or via the phone) and who have expectations beyond the immediate health listened to, questioned, and directed us all before emergency. -

HA16 Rivers and Streams London's Rivers and Streams Resource

HA16 Rivers and Streams Definition All free-flowing watercourses above the tidal limit London’s rivers and streams resource The total length of watercourses (not including those with a tidal influence) are provided in table 1a and 1b. These figures are based on catchment areas and do not include all watercourses or small watercourses such as drainage ditches. Table 1a: Catchment area and length of fresh water rivers and streams in SE London Watercourse name Length (km) Catchment area (km2) Hogsmill 9.9 73 Surbiton stream 6.0 Bonesgate stream 5.0 Horton stream 5.3 Greens lane stream 1.8 Ewel court stream 2.7 Hogsmill stream 0.5 Beverley Brook 14.3 64 Kingsmere stream 3.1 Penponds overflow 1.3 Queensmere stream 2.4 Keswick avenue ditch 1.2 Cannizaro park stream 1.7 Coombe Brook 1 Pyl Brook 5.3 East Pyl Brook 3.9 old pyl ditch 0.7 Merton ditch culvert 4.3 Grand drive ditch 0.5 Wandle 26.7 202 Wimbledon park stream 1.6 Railway ditch 1.1 Summerstown ditch 2.2 Graveney/ Norbury brook 9.5 Figgs marsh ditch 3.6 Bunces ditch 1.2 Pickle ditch 0.9 Morden Hall loop 2.5 Beddington corner branch 0.7 Beddington effluent ditch 1.6 Oily ditch 3.9 Cemetery ditch 2.8 Therapia ditch 0.9 Micham road new culvert 2.1 Station farm ditch 0.7 Ravenbourne 17.4 180 Quaggy (kyd Brook) 5.6 Quaggy hither green 1 Grove park ditch 0.5 Milk street ditch 0.3 Ravensbourne honor oak 1.9 Pool river 5.1 Chaffinch Brook 4.4 Spring Brook 1.6 The Beck 7.8 St James stream 2.8 Nursery stream 3.3 Konstamm ditch 0.4 River Cray 12.6 45 River Shuttle 6.4 Wincham Stream 5.6 Marsh Dykes -

The Digger Wasps of Saudi Arabia: New Records and Distribution, with a Checklist of Species (Hym.: Ampulicidae, Crabronidae and Sphecidae)

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 9 (2): 345-364 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2013 Article No.: 131206 http://biozoojournals.3x.ro/nwjz/index.html The digger wasps of Saudi Arabia: New records and distribution, with a checklist of species (Hym.: Ampulicidae, Crabronidae and Sphecidae) Neveen S. GADALLAH1,*, Hathal M. AL DHAFER2, Yousif N. ALDRYHIM2, Hassan H. FADL2 and Ali A. ELGHARBAWY2 1. Entomology Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt. 2. Plant Protection Department, College of Food and Agriculture Science, King Saud University, King Saud Museum of Arthropod (KSMA), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. *Corresponing author, N.S. Gadalah, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 24. September 2012 / Accepted: 13. January 2013 / Available online: 02. June 2013 / Printed: December 2013 Abstract. The “sphecid’ fauna of Saudi Arabia (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) is listed. A total of 207 species in 42 genera are recorded including previous and new species records. Most Saudi Arabian species recorded up to now are more or less common and widespread mainly in the Afrotropical and Palaearctic zoogeographical zones, the exception being Bembix buettikeri Guichard, Bembix hofufensis Guichard, Bembix saudi Guichard, Cerceris constricta Guichard, Oxybelus lanceolatus Gerstaecker, Palarus arabicus Pulawski in Pulawski & Prentice, Tachytes arabicus Guichard and Tachytes fidelis Pulawski, which are presumed endemic to Saudi Arabia (3.9% of the total number of species). General distribution and ecozones, and Saudi Arabian localities are given for each species. In this study two genera (Diodontus Curtis and Dryudella Spinola) and 11 species are newly recorded from Saudi Arabia. Key words: Ampulicidae, Crabronidae, Sphecidae, faunistic list, new records, Saudi Arabia. Introduction tata boops (Schrank), Bembecinus meridionalis A.Costa, Diodontus sp. -

The London Rivers Action Plan

The london rivers action plan A tool to help restore rivers for people and nature January 2009 www.therrc.co.uk/lrap.php acknowledgements 1 Steering Group Joanna Heisse, Environment Agency Jan Hewlett, Greater London Authority Liane Jarman,WWF-UK Renata Kowalik, London Wildlife Trust Jenny Mant,The River Restoration Centre Peter Massini, Natural England Robert Oates,Thames Rivers Restoration Trust Kevin Reid, Greater London Authority Sarah Scott, Environment Agency Dave Webb, Environment Agency Support We would also like to thank the following for their support and contributions to the programme: • The Underwood Trust for their support to the Thames Rivers Restoration Trust • Valerie Selby (Wandsworth Borough Council) • Ian Tomes (Environment Agency) • HSBC's support of the WWF Thames programme through the global HSBC Climate Partnership • Thames21 • Rob and Rhoda Burns/Drawing Attention for design and graphics work Photo acknowledgements We are very grateful for the use of photographs throughout this document which are annotated as follows: 1 Environment Agency 2 The River Restoration Centre 3 Andy Pepper (ATPEC Ltd) HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE This booklet is to be used in conjunction with an interactive website administered by the The River Restoration Centre (www.therrc.co.uk/lrap.php).Whilst it provides an overview of the aspirations of a range of organisations including those mentioned above, the main value of this document is to use it as a tool to find out about river restoration opportunities so that they can be flagged up early in the planning process.The website provides a forum for keeping such information up to date. -

Annual Report 2007 2008

1946 Mind Annual Report 6/10/08 11:15 Page 1 Richmond Borough Mind Annual Report 1946 Mind Annual Report 6/10/08 11:15 Page 2 April 2007-March 2008 Achievements and Performance This has been another year of change, as the Recovery Approach was Carers Support & Training introduced throughout the statutory mental health services in Richmond, We welcome the new Carers Strategy 2007-2010, a challenge to us all in Richmond Borough Mind to adapt to new, more whose aims include improved well being and quality of life for carers; making sure their contribution is outward looking, positive and empowering ways of working. recognised; increasing choice, control and information and providing training for carers and professionals. We continued to shape our service so it has a key role in In line with our strategic aims, we sought to modernise As an organisation, we have become stronger in the realising these aims: investigating the use of Carers and diversify our services throughout the year, tailoring course of the year, securing income for more frequent Vouchers, increasing the resources of our information activities at our drop-ins to attract a wide spectrum of in-house support and training for our staff, and library; and making funding bids for well being sessions. service users and fundraising for resources to move into working to strengthen our infrastructure in order to new fields like TimeBanking, Befriending and work to employ a Finance Officer and an Administrative The three support groups continued to meet in support Peer-Support groups. Later in the year, we Assistant as well as volunteers. -

HOST PLANTS of SOME STERNORRHYNCHA (Phytophthires) in NETHERLANDS NEW GUINEA (Homoptera)

Pacific Insects 4 (1) : 119-120 January 31, 1962 HOST PLANTS OF SOME STERNORRHYNCHA (Phytophthires) IN NETHERLANDS NEW GUINEA (Homoptera) By R. T. Simon Thomas DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS, HOLLANDIA In this paper, I list 15 hostplants of some Phytophthires of Netherlands New Guinea. Families, genera within the families and species within the genera are mentioned in alpha betical order. The genera and the specific names of the insects are printed in bold-face type, those of the plants are in italics. The locality, where the insects were found, is printed after the host plants. Then follows the date of collection and finally the name of the collector1 in parentheses. I want to acknowledge my great appreciation for the identification of the Aphididae to Mr. D. Hille Ris Lambers and of the Coccoidea to Dr. A. Reyne. Aphididae Cerataphis variabilis Hrl. Cocos nucifera Linn.: Koor, near Sorong, 26-VII-1961 (S. Th.). Longiunguis sacchari Zehntner. Andropogon sorghum Brot.: Kota Nica2 13-V-1959 (S. Th.). Toxoptera aurantii Fonsc. Citrus sp.: Kota Nica, 16-VI-1961 (S. Th.). Theobroma cacao Linn.: Kota Nica, 19-VIII-1959 (S. Th.), Amban-South, near Manokwari, 1-XII- 1960 (J. Schreurs). Toxoptera citricida Kirkaldy. Citrus sp.: Kota Nica, 16-VI-1961 (S. Th.). Schizaphis cyperi v. d. Goot, subsp, hollandiae Hille Ris Lambers (in litt.). Polytrias amaura O. K.: Hollandia, 22-V-1958 (van Leeuwen). COCCOIDEA Aleurodidae Aleurocanthus sp. Citrus sp.: Kota Nica, 16-VI-1961 (S. Th.). Asterolecaniidae Asterolecanium pustulans (Cockerell). Leucaena glauca Bth.: Kota Nica, 8-X-1960 (S. Th.). 1. My name, as collector, is mentioned thus: "S. -

Upper Tideway (PDF)

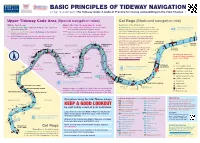

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA -

Downloaded from BOLD Or Requested from Other Authors

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Towards a global DNA barcode reference library for quarantine identifcations of lepidopteran Received: 28 November 2018 Accepted: 5 April 2019 stemborers, with an emphasis on Published: xx xx xxxx sugarcane pests Timothy R. C. Lee 1, Stacey J. Anderson2, Lucy T. T. Tran-Nguyen3, Nader Sallam4, Bruno P. Le Ru5,6, Desmond Conlong7,8, Kevin Powell 9, Andrew Ward10 & Andrew Mitchell1 Lepidopteran stemborers are among the most damaging agricultural pests worldwide, able to reduce crop yields by up to 40%. Sugarcane is the world’s most prolifc crop, and several stemborer species from the families Noctuidae, Tortricidae, Crambidae and Pyralidae attack sugarcane. Australia is currently free of the most damaging stemborers, but biosecurity eforts are hampered by the difculty in morphologically distinguishing stemborer species. Here we assess the utility of DNA barcoding in identifying stemborer pest species. We review the current state of the COI barcode sequence library for sugarcane stemborers, assembling a dataset of 1297 sequences from 64 species. Sequences were from specimens collected and identifed in this study, downloaded from BOLD or requested from other authors. We performed species delimitation analyses to assess species diversity and the efectiveness of barcoding in this group. Seven species exhibited <0.03 K2P interspecifc diversity, indicating that diagnostic barcoding will work well in most of the studied taxa. We identifed 24 instances of identifcation errors in the online database, which has hampered unambiguous stemborer identifcation using barcodes. Instances of very high within-species diversity indicate that nuclear markers (e.g. 18S, 28S) and additional morphological data (genitalia dissection of all lineages) are needed to confrm species boundaries. -

Phragmites Australis

Journal of Ecology 2017, 105, 1123–1162 doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12797 BIOLOGICAL FLORA OF THE BRITISH ISLES* No. 283 List Vasc. PI. Br. Isles (1992) no. 153, 64,1 Biological Flora of the British Isles: Phragmites australis Jasmin G. Packer†,1,2,3, Laura A. Meyerson4, Hana Skalov a5, Petr Pysek 5,6,7 and Christoph Kueffer3,7 1Environment Institute, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; 3Institute of Integrative Biology, Department of Environmental Systems Science, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich, CH-8092, Zurich,€ Switzerland; 4University of Rhode Island, Natural Resources Science, Kingston, RI 02881, USA; 5Institute of Botany, Department of Invasion Ecology, The Czech Academy of Sciences, CZ-25243, Pruhonice, Czech Republic; 6Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, CZ-12844, Prague 2, Czech Republic; and 7Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Matieland 7602, South Africa Summary 1. This account presents comprehensive information on the biology of Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. (P. communis Trin.; common reed) that is relevant to understanding its ecological char- acteristics and behaviour. The main topics are presented within the standard framework of the Biologi- cal Flora of the British Isles: distribution, habitat, communities, responses to biotic factors and to the abiotic environment, plant structure and physiology, phenology, floral and seed characters, herbivores and diseases, as well as history including invasive spread in other regions, and conservation. 2. Phragmites australis is a cosmopolitan species native to the British flora and widespread in lowland habitats throughout, from the Shetland archipelago to southern England. -

Outdoor Learning Providers in the Borough

Providers of Outdoor Learning in Richmond Environmental, Friends of Parks and Residents Groups Environment Trust Website: www.environmenttrust.co.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8891 5455 Contact: Stephen James Events are advertised on http://www.environmenttrust.co.uk/whats-on Friends of Barnes Common Website: www.barnescommon.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 07855 548 404 Contact: Sharon Morgan Events are advertised on www.barnescommon.org.uk/learning Friends of Bushy and Home Parks Website: www.fbhp.org.uk Email: [email protected] Events are advertised on www.fbhp.org.uk/walksandtalks Green Corridor Land based horticultural qualifications for young people aged 14-35. Website: www.greencorridor.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 01403 713 567 Contact: Julie Docking Updated March 2016 Friends of the River Crane Environment (FORCE) Website: www.force.org.uk Email: [email protected] For walks and talks, community learning, and outdoor learning for schools in sites in the lower Crane Valley see http://e-voice.org.uk/force/calendar/view Friends of Carlisle Park Website: http://e-voice.org.uk/friendsofcarlislepark/ Ham United Group Website: www.hamunitedgroup.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8940 2941 Contact: Penny Frost River Thames Boat Project Educational, therapeutic and recreational cruises and activities on the River Thames. Website: www.thamesboatproject.org Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8940 3509 Contact: Pippa Thames Explorer Trust Website: www.thames-explorer.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8742 0057 Contact: Lorraine Conterio or Simon Clarke Summer playscheme - www.thames-explorer.org.uk/families/summer-playscheme Foreshore walks - www.thames-explorer.org.uk/foreshore-walks/ YMCA London South West Website: www.ymcalsw.org Contact: Myke Catterall Updated March 2016 Thames Young Mariners Thames Young Mariners in Ham offer outdoor learning opportunities for schools, youth groups, families and adults all year round including day and residential visits. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Download This Article in PDF Format

Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2018, 419, 42 Knowledge & © K. Pabis, Published by EDP Sciences 2018 Management of Aquatic https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2018030 Ecosystems www.kmae-journal.org Journal fully supported by Onema REVIEW PAPER What is a moth doing under water? Ecology of aquatic and semi-aquatic Lepidoptera Krzysztof Pabis* Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Hydrobiology, University of Lodz, Banacha 12/16, 90-237 Lodz, Poland Abstract – This paper reviews the current knowledge on the ecology of aquatic and semi-aquatic moths, and discusses possible pre-adaptations of the moths to the aquatic environment. It also highlights major gaps in our understanding of this group of aquatic insects. Aquatic and semi-aquatic moths represent only a tiny fraction of the total lepidopteran diversity. Only about 0.5% of 165,000 known lepidopterans are aquatic; mostly in the preimaginal stages. Truly aquatic species can be found only among the Crambidae, Cosmopterigidae and Erebidae, while semi-aquatic forms associated with amphibious or marsh plants are known in thirteen other families. These lepidopterans have developed various strategies and adaptations that have allowed them to stay under water or in close proximity to water. Problems of respiratory adaptations, locomotor abilities, influence of predators and parasitoids, as well as feeding preferences are discussed. Nevertheless, the poor knowledge on their biology, life cycles, genomics and phylogenetic relationships preclude the generation of fully comprehensive evolutionary scenarios. Keywords: Lepidoptera / Acentropinae / caterpillars / freshwater / herbivory Résumé – Que fait une mite sous l'eau? Écologie des lépidoptères aquatiques et semi-aquatiques. Cet article passe en revue les connaissances actuelles sur l'écologie des mites aquatiques et semi-aquatiques, et discute des pré-adaptations possibles des mites au milieu aquatique.