Pahiatua Region and the Second World War 1939 – 45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology of the Wairarapa Area

GEOLOGY OF THE WAIRARAPA AREA J. M. LEE J.G.BEGG (COMPILERS) New International NewZOaland Age International New Zealand 248 (Ma) .............. 8~:~~~~~~~~ 16 il~ M.- L. Pleistocene !~ Castlecliffian We £§ Sellnuntian .~ Ozhulflanl Makarewan YOm 1.8 100 Wuehlaplngien i ~ Gelaslan Cl Nukumaruan Wn ~ ;g '"~ l!! ~~ Mangapanlan Ql -' TatarianiMidian Ql Piacenzlan ~ ~;: ~ u Wai i ian 200 Ian w 3.6 ,g~ J: Kazanlan a.~ Zanetaan Opoitian Wo c:: 300 '"E Braxtonisn .!!! .~ YAb 256 5.3 E Kunaurian Messinian Kapitean Tk Ql ~ Mangapirian YAm 400 a. Arlinskian :;; ~ l!!'" 500 Sakmarian ~ Tortonisn ,!!! Tongaporutuan Tt w'" pre-Telfordian Ypt ~ Asselian 600 '" 290 11.2 ~ 700 'lii Serravallian Waiauan 5w Ql ." i'l () c:: ~ 600 J!l - fl~ '§ ~ 0'" 0 0 ~~ !II Lillburnian 51 N 900 Langhian 0 ~ Clifdenian 5e 16.4 ca '1000 1 323 !II Z'E e'" W~ A1tonian PI oS! ~ Burdigalian i '2 F () 0- w'" '" Dtaian Po ~ OS Waitakian Lw U 23.8 UI nlan ~S § "t: ." Duntroonian Ld '" Chattian ~ W'" 28.5 P .Sll~ -''" Whalngaroan Lwh O~ Rupelian 33.7 Late Priabonian ." AC 37.0 n n 0 I ~~ ~ Bortonian Ab g; Lutetisn Paranaen Do W Heretauncan Oh 49.0 354 ~ Mangaorapan Om i Ypreslan .;;: w WalD8wsn Ow ~ JU 54.8 ~ Thanetlan § 370 t-- §~ 0'" ~ Selandian laurien Dt ." 61.0 ;g JM ~"t: c:::::;; a.os'"w Danian 391 () os t-- 65.0 '2 Maastrichtian 0 - Emslsn Jzl 0 a; -m Haumurian Mh :::;; N 0 t-- Campanian ~ Santonian 0 Pragian Jpr ~ Piripauan Mp W w'" -' t-- Coniacian 1ij Teratan Rt ...J Lochovlan Jlo Turonian Mannaotanean Rm <C !II j Arowhanan Ra 417 0- Cenomanian '" Ngaterian Cn Prldoli -

The 1934 Pahiatua Earthquake Sequence: Analysis of Observational and Instrumental Data

221 THE 1934 PAHIATUA EARTHQUAKE SEQUENCE: ANALYSIS OF OBSERVATIONAL AND INSTRUMENTAL DATA Gaye Downes1' 2, David Dowrick1' 4, Euan Smith3' 4 and Kelvin Berryman1' 2 ABSTRACT Descriptive accounts and analysis of local seismograms establish that the epicentre of the 1934 March 5 M,7.6 earthquake, known as the Pahiatua earthquake, was nearer to Pongaroa than to Pahiatua. Conspicuous and severe damage (MM8) in the business centre of Pahiatua in the northern Wairarapa led early seismologists to name the earthquake after the town, but it has now been found that the highest intensities (MM9) occurred about 40 km to the east and southeast of Pahiatua, between Pongaroa and Bideford. Uncertainties in the location of the epicentre that have existed for sixty years are now resolved with the epicentre determined in this study lying midway between those calculated in the 1930' s by Hayes and Bullen. Damage and intensity summaries and a new isoseismal map, derived from extensive newspaper reports and from 1934 Dominion Observatory "felt reports", replace previous descriptions and isoseismal maps. A stable solution for the epicentre of the mainshock has been obtained by analysing phase arrivals read from surviving seismograms of the rather small and poorly equipped 1934 New Zealand network of twelve stations (two privately owned). The addition of some teleseismic P arrivals to this solution shifts the location of the epicentre by less than 10 km. It lies within, and to the northern end of, the MM9 isoseismal zone. Using local instrumental data larger aftershocks and other moderate magnitude earthquakes that occurred within 10 days and 50 km of the mainshock have also been located. -

Wairarapa Train Services: Survey Results

Wairarapa train services: survey results Introduction Greater Wellington Regional Council carried out a survey of passengers on the north-bound Wairarapa trains on 22 June 2011 as part of the Wairarapa Public Transport Service Review. A total of 725 completed forms were returned. We would like to thank passengers and train-staff for your help with this survey. A summary of the results are shown below. The full survey report is available at www.gw.govt.nz/wairarapareview Where people live and how they get to the station About 25% of passengers live in each of Masterton, Carterton or Featherston. A further 13% of passengers live in Greytown and 6% in Martinborough. Sixty-eight percent of passengers travel to the station by car (57% parking their car at the station and 11% being dropped off). A further 23% of passengers walk or cycle to the station and 7% use the bus. Origin and destination The main boarding station in Wairarapa is Featherston (33%), followed by Masterton (28%), Carterton (25%) and Woodside (12%). Most passengers (85%) are going to Wellington, with the rest (15%) going to the Hutt Valley. Why people use the train, and purpose and frequency of travel The main reason people said they use the train is because it is cheaper than taking the car (56% of passengers) and a significant number also said it is quicker than driving (29% of passengers). Comfort (45% of passengers) and ability to work on the train (47% of passengers) were also important. Twenty-six percent of passengers also indicated that it’s environmentally responsible and 20% said they had no other transport option. -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No

1050 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 37 Amount Date Persons Believed to be Entitled Held Received $ Shaw, J., Featherston 2.40 20/9/68 Shaw, T., Greytown .. 24.00 20/9/68 Sheath, A., Masterton 12.00 20/9/68 Sheehyn, M. J., Eketahuna 4.80 29/9/68 Shekleton, A. B., Pahiatua 12.00 20/9/68 Sheppard, W. S., Mangatainoka 2.40 20/9/68 Shirkey, J., French Street, Martinborough 2.40 20/9/68 Shirkey, J., Martinborough 4.80 20/9/68 Shirtciiffe, W. S., Mangatainoka 2.40 20/9/68 Short, G., 175 The Terrace, Wellington .. 2.40 20/9/68 Sibbald, L. S. T., Owendale, Saunders Road, Eketahuna 2.40 20/9/68 Siemonex, E., High Street, Masterton 2.40 20/9/68 Signertsen, J. P., Rongokokako 2.40 20/9/68 Simmers, E. M., Eketahuna 4.80 20/9/68 Simmonds, H., Parkville 2.40 20/9/68 Simmonds, W. D., Ashby's Line, South Featherston 2.40 20/9/68 Simms, F. R., 40 Raroa Road, Kelburn, Wellington 2.40 20/9/68 Simpson, W., Eketahuna 4.80 20/9/68 Sisson, J., Matamau 4.80 20/9/68 Skerman, J. A. (executors), care of A. A. Podeviw, Te Kuiti 40.00 20/9/68 Skipwith, R. H., Melwood, Dannevirke 4.80 20/9/68 Slacke, R. H., Mangamutu, Pahiatua 2.40 20/9/68 Sladden, H., Woburn Road, Lower Hutt 2.40 20/9/68 Small, C. F., Penrose, Masterton 2.40 20/9/68 Small, R. M., Eketahuna 2.40 20/9/68 Small, W. -

BEFORE the HEARING PANEL in the MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 and in the MATTER of Application by Tararua Distric

BEFORE THE HEARING PANEL IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND IN THE MATTER of application by Tararua District Council to Horizons Regional Council for application APP-1993001253.02 for resource consents associated with the operation of the Pahiatua Wastewater Treatment Plant, including earthworks, a discharge to Town Creek (initially) then to the Mangatainoka River, a discharge to air (principally odour), and discharges to land via seepage, Julia Street, Pahiatua SUPPLEMENTARY EVIDENCE OF ADAM DOUGLAS CANNING (FRESHWATER ECOLOGY) FOR THE WELLINGTON FISH AND GAME COUNCIL 19 May 2017 1. My name is Adam Douglas Canning. I am a Freshwater Ecologist and my credentials are presented in my Evidence in Chief (EiC). Response to questions asked to me by the commissioners in Memorandum 3 To Participants (15 May 2017). 2. “In respect of Figure 1 on page 4 of Mr Canning’s evidence: i) Whereabouts in the Mangatainoka River were the Figure 1 measurements made? ii) If that is the type of pattern that might be caused by the Pahiatua WWTP discharge, how far downstream might it extend?” i) The diurnal dissolved oxygen fluctuations depicted in Figure 1 were made above shortly above the confluence with the Makakahi River (40˚28’36”S, 175˚47’14”N) (Wood et al., 2015). Therefore, the readings are well above, and consequently unaffected by, the Pahiatua Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP). The readings should not be taken as depicting the impact of the WWTP. Rather they show that a) the Mangatainoka River is in poor ecological health well before the WWTP; b) that extreme diurnal fluctuations in dissolved oxygen can and do occur in the Mangatainoka River; and c) increased nutrient inputs by the WWTP would likely exacerbate existing diurnal fluctuations and further reduce ecological health (as explained in my EiC). -

The Where and What

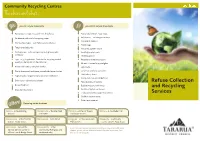

Community Recycling Centres The where and what... Yes you can recycle these items No you cannot recycle these items z Newspapers, magazines, junk mail, brochures z Household rubbish, food waste z Cardboard and non-foil wrapping paper z Polystyrene – including meat trays z Disposable nappies z Dry food packages – e.g. flattened cereal boxes z Plastic bags z Telephone directories z Hot ashes, garden waste z Writing paper, and envelopes (including those with z Seedling or plant pots windows) z Drinking glasses z Type 1, 2, 3, & 5 plastics – look for the recycling symbol, z Window or windscreen glass usually at the bottom of the container z Mirrors – frosted or crystal glass z Plastic milk bottles, soft drink bottles z Light bulbs z Plastic shampoo/conditioner, household cleaner bottles z Ceramics, crockery, porcelain z Old clothes, shoes z Yoghurt pots, margarine tubs, ice-cream containers z Computers, household batteries z Drink cans – aluminium and steel z Toys, buckets, or baskets Refuse Collection z Rinsed food tins z Bubble wrap or shrink wrap and Recycling z Glass bottles and jars z Paint tins, fuel oil containers z Containers/bottles larger than 4 litres Services z Shellfish and fish waste z Other toxic material Where Recycling centre locations Akitio – at the camping Herbertville – Tautane Road Pahiatua – corner of Queen Weber – at the Weber Hall ground intersetion and Tudor Streets Dannevirke – at the Transfer Norsewood – Odin Street Pongaroa – in the Community Woodville – Community Station, Easton Street Hall carpark Centre carpark, Ross Street Eketahuna – behind the Ormondville – at the If you have any queries regarding recycling, or any other solid waste Service Centre, corner of Community Hall (glass and matters, please call our Waste Services Contracts Supervisor, Pete Wilson Lane & Bridge Street cardboard only) Sinclair, on 06 374 4080. -

Benthic Cyanobacteria Blooms in Rivers in the Wellington Region Findings from a Decade of Monitoring and Research

Benthic cyanobacteria blooms in rivers in the Wellington Region Findings from a decade of monitoring and research Benthic cyanobacteria blooms in rivers in the Wellington Region Findings from a decade of monitoring and research MW Heath S Greenfield Environmental Science Department For more information, contact the Greater Wellington Regional Council: Wellington Masterton GW/ESCI-T-16/32 PO Box 11646 PO Box 41 ISBN: 978-1-927217-90-0 (print) ISBN: 978-1-927217-91-7 (online) T 04 384 5708 T 06 378 2484 F 04 385 6960 F 06 378 2146 June 2016 www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz [email protected] Report prepared by: MW Heath Environmental Scientist S Greenfield Senior Environmental Scientist Report reviewed by: J Milne Team Leader, Aquatic Ecosystems & Quality Report approved for release by: L Butcher Manager, Environmental Science Date: June 2016 DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by Environmental Science staff of Greater Wellington Regional Council (GWRC) and as such does not constitute Council policy. In preparing this report, the authors have used the best currently available data and have exercised all reasonable skill and care in presenting and interpreting these data. Nevertheless, GWRC does not accept any liability, whether direct, indirect, or consequential, arising out of the provision of the data and associated information within this report. Furthermore, as GWRC endeavours to continuously improve data quality, amendments to data included in, or used in the preparation of, this report may occur without notice at any time. GWRC requests that if excerpts or inferences are drawn from this report for further use, due care should be taken to ensure the appropriate context is preserved and is accurately reflected and referenced in subsequent written or verbal communications. -

Life After Pahiatua

Life After Pahiatua On 1 November 1944 a total of 733 Polish children and their 105 guardians landed in Wellington Harbour. Together they had shared the fate of 1.7 million Poles who had been ethnically cleansed from their homes in eastern Poland under Stalin’s orders at the start of World War II and deported to forced-labour camps throughout the Soviet Union. Of those 1.7 million, 1 million died and 200,000 are still unaccounted for in Stalin’s genocide. This group of children, mostly orphaned or having lost family members, were the lucky ones and found eventual refuge in the Polish Children’s Camp in Pahiatua and a permanent home in New Zealand. These are the stories of their lives after the camp of how they successfully integrated and contributed to New Zealand society, more than repaying their debt to the country that offered them refuge and care in their time of need. Life After Pahiatua Contents Marian Adamski 1 Halina Morrow (nee Fladrzyńska) 25 Anna Aitken (nee Zazulak) 2 Teresa Noble-Campbell (nee Ogonowska) 26 Maria Augustowicz (nee Zazulak) 3 Janina Ościłowska (nee Łabędź) 27 Józefa Berry (nee Węgrzyn) 4 Czesława Panek (nee Wierzbińska) 28 Ryszard Janusz Białostocki 5 Genowefa Pietkiewicz (nee Knap) 29 Henryka Blackler (nee Aulich) 6 Władysław Pietkiewicz 30 Irena Coates (nee Ogonowska) 7 Franciszka Quirk (nee Węgrzyn) 31 Witold Domański 8 Kazimierz Rajwer 32 Krystyna Downey (nee Kołodyńska) 9 John Roy-Wojciechowski 33 Janina Duynhoven (nee Kornobis) 10 Malwina Zofia Schwieters (nee Rubisz) 34 Henryk Dziura 11 Michał Sidoruk -

Very Wet in Many Parts and an Extremely Cold Snap for the South

New Zealand Climate Summary: June 2015 Issued: 3 July 2015 Very wet in many parts and an extremely cold snap for the south. Rainfall Rainfall was above normal (120-149%) or well above normal (> 149%) for much of the Manawatu-Whanganui, Taranaki, Westland, Tasman, Nelson, Marlborough, Canterbury, Otago, and Southland regions. Rainfall was well below normal (< 50%) or below normal (50-79%) for parts of Northland, Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay, and north Canterbury. Temperature June temperatures were near average across much of the country (within 0.5°C of June average). Below average temperatures were recorded in inland Canterbury, Wairarapa, western Waikato (0.5-1.2°C below June average) and above average temperatures experienced in northern, eastern, and western parts of the North Island and northern, western, and south-central parts of the South Island (0.5-1.2°C above June average). A polar outbreak in late June led to the 4th-lowest temperature ever recorded in New Zealand. Soil Moisture As of 1 July 2015, soil moisture levels were below normal for this time of year for East Cape, around and inland from Napier, coastal Wairarapa, coastal southern Marlborough and eastern parts of Canterbury north of Christchurch. It was especially dry about north Canterbury where soils were considerably drier than normal for this time of year. Sunshine Well above normal (>125%) or above normal (110-125%) sunshine was recorded in Northland, Auckland, western Waikato, Wellington, Marlborough, north Canterbury, and Central Otago. Near normal sunshine (within 10% of normal) was recorded elsewhere, expect in Franz Josef and Tauranga where below normal sunshine was recorded. -

Agenda of Council Meeting

Notice of Meeting A meeting of the Tararua District Council will be held in the Council Chamber, 26 Gordon Street, Dannevirke on Wednesday 27 January 2021 commencing at 1.00pm. Bryan Nicholson Chief Executive Agenda 1. Present 2. Council Prayer 3. Apologies 4. Public Forum A period of up to 30 minutes shall be set aside for a public forum. Each speaker during the public forum section of a meeting may speak for up to five minutes. Standing Orders may be suspended on a vote of three-quarters of those present to extend the period of public participation or the period any speaker is allowed to speak. With the permission of the Mayor, members may ask questions of speakers during the period reserved for public forum. If permitted by the Mayor, questions by members are to be confined to obtaining information or clarification on matters raised by the speaker. 5. Notification of Items Not on the Agenda Major items not on the agenda may be dealt with at this meeting if so resolved by the Council and the chairperson explains at the meeting at a time when it is open to the public the reason why the item was not listed on the agenda and the reason why discussion of the item cannot be delayed until a subsequent meeting. Minor matters not on the agenda relating to the general business of the Council may be discussed if the chairperson explains at the beginning of the meeting, at a time when it is open to the public, that the item will be discussed at that meeting, but no resolution, decision or recommendation may be made in respect of that item except to refer it to a subsequent meeting. -

The New Zealand Gazette. 1741

JUNE 24.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 1741 MILITARY AREA No. 7 (N.APIER)-contiiiued. MILITARY AREA No. 7 (NAPIER)-contin1fed. 511030 Beck, Wt1,lter Allan, chemist, 83 Vigor Brown St. 628308 Braddick, Kevin Michael, farm labourer, Mangatainoka, 628150 Beckett, James, Tumor's Estate, Eketahuna. Pahiatua. 626257 Bee, John Stainton, shepherd, Bag 91, Wairoa. 518597 Brader, Robert Vincent, painter and paperhanger, 48. 562019 Beer, Charles, carpenter, 1 Bryce St., Mangapapa, Gisborne. Bannister St., Masterton. 504876 Beets, Walter Albert, tablet porter (N.Z.R.), Hatuma. 555079 Bradley, Gordon Stewart, farmer, Papatawa, Woodville. 496456 Beets, William Ford, labourer, Matawhero, Gisborne. 483504 Bradley, James, truck-driver, Queen St., Wairoa. 553222 Begg, Allan George, driver, Omahanui, Wairoa. 535041 Bradley, John William, fruiterer, 409 Avenue West, Hastings. 564922 Beggs, Joseph, tunneller, Piripaua, Tuai. 5M773 Brady, Philip Patrick, billiard-saloon proprietor, 30 Wainui 460043 Bell, Archibald, clerk, 105 Wellesley Rd. Rd., Gisborne. 535500 Bell, Arthur George, medical practitioner, Consitt St., 531804 Brain, Norman Robert, casual worker, 2 Marlborough St., Takapau. Waipukurau. 552658 Bell, David l\foncrieff, departmental manager, 33 Centennial · 466093 Bramley, George Hugo, clerk, 102 Stafford St., Gisborne. Cres., Gisborne. 532729 Brand, James George, field inspector, 20 Pownall St., 522004 Bell, Gladstone Henry, school-teacher, 31 Fitzroy Rd. Masterton. 613822 Bell, William Johnston, storeman, Lahore St., Wairoa. 602317 B~annigan, William Frederick Doinnion, farm labourer, 627190 Bellamy, ]\fax Victor, rabbiter, care of Mrs. V. M. Bellamy, 74 Sedcole St., Pahiatua. Ormondville. 521356 Breakwell, Lester Herbert, stock-buyer, Duart Rd., Havelock 530465 Bengston, Henry Saunders, mill hand, Tudor St., Pahiatua. North. 517150 Bennett, Frederick, wool-classer, Darwin Rd., Kaiti, Gis 628274 Bretherton, Peter Thomas, grocer's assistant, McLean St., borne. -

Find Your Nearest Z Truck Stop

Truck Stop Key In addition to fuels and oils, the following products and services are available as indicated (services available during site trading hours) S Z Service station nearby T Toilet available Z Z DEC available Waipapa NORTHLAND TIRAU TAUMARUNUI Z Z Tirau Z Taumarunui WAIPAPA Cnr State Highway 1 and State Highway 4 Northland Z Waipapa State Highway 27 1913 State Highway 10 TAUPO Whangarei Z TOKOROA Z Miro St WHANGAREI Z Tokoroa 63 Miro Street Find your nearest Z Whangarei Browning Street Kioreroa Road TAUPO WAHAROA T Z Taupo GREATER AUCKLAND Z Waharoa Cnr Rakaunui Road and Z truck stop Factory Road Off Road Highway S T EAST TAMAKI S T Z Z Harris Road BAY OF PLENTY & TURANGI 142 Harris Road Z Turangi NORTH ISLAND THAMES VALLEY Atirau Road HIGHBROOK S T Z WHAKATANE S T WAIOURU S T Z Highbrook Z Awakeri 88 Highbrook Drive Z Waiouru State Highway 30 State Highway 1 S T Auckland MAIRANGI BAY S T Z Z Constellation Dr MT MAUNGANUI WAITARA Z Hewletts Rd Z Waitara Pokeno Cnr Constellation Drive 81 Hewletts Road Bay of Plenty/ and Vega Place Cnr Raleigh Street and Ngatea S T State Highway 3 S T NGATEA Maramarua Thames Valley MANUKAU CITY Z Ngatea Z Lakewood Court 77 Orchard Road MANAWATU, WAIRARAPA 742 Great South Road Mount Maunganui ROTORUA Z & HOROWHENUA Ngaruwahia MASSEY NORTH S T Z Rotorua DANNEVIRKE HAMILTON Z Massey North Sala Street Waharoa Cnr State Highway 16 Z Dannevirke and Asti Lane ROTORUA S T State Highway 2, Matamau Tirau Whakatane Te Awamutu Putaruru T Z Z Fairy Springs LEVIN S MT WELLINGTON 23 Fairy Springs Road Rotorua