LUCAS® Chest Compression System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of Endotracheal Intubation with the Airtraq

Disaster and Emergency Medicine Journal 2016, Vol. 1, No. 1, 7–13 ORIGINAL PAPER DOI: 10.5603/DEMJ.2016.0002 Copyright © 2016 Via Medica ISSN 2451–4691 COMPARISON OF ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION WITH THE AIRTRAQ AVANT® AND THE MACINTOSH LARYNGOSCOPE DURING INTERMITTENT OR CONTINUOUS CHEST COMPRESSION: A RANDOMIZED, CROSSOVER STUDY IN MANIKINS Michael Frass1, Oliver Robak1, Zenon Truszewski2, Lukasz Czyzewski3, Lukasz Szarpak2 1Department of Internal Medicine I, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland 3Department of Nephrologic Nursing, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland ABSTRACT BACKGROUND: Endotracheal intubation (ETI) currently is the gold standard of securing an airway during cardio- pulmonary resuscitation. PURPOSE: The aim of this study was to evaluate ETI with the Airtraq Avant (ATQ) compared to a conventional Macintosh laryngoscope when used by paramedics during resuscitation with and without chest compression (CC). METHODS: Forty-seven paramedics were recruited into a randomized crossover trial in which each performed ETI with ATQ and MAC in both scenarios. The primary endpoint was time to successful intubation, while secondary endpoints included intubation success, laryngoscopic view on the glottis, dental compression, and rating of the given device. RESULTS: In the manikin scenario without CC, nearly all participants performed ETI successfully both with ATQ and MAC, with a shorter intubation time using MAC 20.5 s [IQR, 17.5–22], compared to ATQ 24.5 s [IQR, 22–27.5] (p = 0.002). However, in the scenarios with continuous CC, the results with ATQ were significantly better than with MAC for all analyzed variables (success of first attempt at ETI, time to intubation (TTI) [MAC 27 s [IQR, 25.5–34.5], compared to ATQ 25.7 s [IQR, 21.5–28.5] (p = 0.011), Cormack-Lehane grade and rating). -

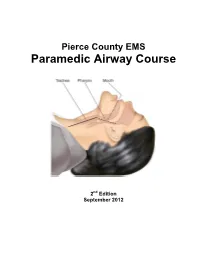

Paramedic Airway Management Course

Pierce County EMS Paramedic Airway Course 2nd Edition September 2012 Pierce County EMS Paramedic Airway Management Course Table of Contents: Acknowledgements ............................................................................................ 3 Course Purpose and Description ..................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................................ 5 Assessing the Need for Emergency Airway Management ............................. 6 Effective Use of the Bag-Valve Mask ............................................................... 7 Endotracheal Intubation—Preparing for First Pass Success ........................ 8 RSI & Endotracheal Intubation ....................................................................... 11 Confirming, Securing and Monitoring Airway Placement ............................ 15 Use of Alternative “Rescue Airways” ............................................................ 16 Surgical Airways .............................................................................................. 17 Emergency Airway Management in Special Populations: ........................... 18 Pediatric Patients Geriatric Patients Trauma Patients Bariatric Patients Pregnant Patients Ten Tips for Best Practices in Emergency Airway Management ................ 21 Airway Performance Documentation and CQI Analysis ............................... 22 Conclusion ...................................................................................................... -

Hypothermia for Traumatic Brain Injury in Children Corticosteroids Don't

From the publishers of The New England Journal of Medicine July 2008 Vol. 12 No. 7 Hypothermia for ated with an unfavorable outcome, the Hutchison JS et al. Hypothermia therapy odds ratio for an unfavorable outcome after traumatic brain injury in children. Traumatic Brain Injury with hypothermia therapy was 2.33. N Engl J Med 2008 Jun 5; 358:2447. in Children Death rates did not differ significantly nimal models and small studies in between the hypothermia and normo- A children and adults suggest a bene- thermia groups (21% vs. 12%). No evi- Corticosteroids Don’t fit for hypothermia therapy in the treat- dence of benefit was detected in analy- Reduce Mortality ment of severe traumatic brain injury. ses of any of eight subgroups, including patients who were treated early. in Children with In an international trial, researchers Bacterial Meningitis compared outcomes in children (age Comment: range, 1–17 years) with traumatic brain This study was remarkably ambitious, dministration of adjuvant cortico- injury who were randomized to either given the low incidence of eligible pa- A steroids mitigates hearing loss in hypothermia therapy for 24 hours tients (5 per month in 17 pediatric children with Haemophilus influenzae (32.0°C–33.0°C) or normothermia hospitals in 3 countries). Despite this type B (Hib) meningitis. However, the (36.5°C–37.5°C). Eligible patients had obstacle, the researchers showed un- introduction of vaccines against Hib in Glasgow Coma Scale scores 8 at the ≤ equivocally that hypothermia has no 1985 and against Streptococcus pneu- scene or in the emergency department, benefit. -

Public Health Administration Pre-Hospital Services Committee August 11, 2011 Large Conference Room Agenda 9:30 A.M

Public Health Administration Pre-hospital Services Committee August 11, 2011 Large Conference Room Agenda 9:30 a.m. 2240 E. Gonzales, 2nd Floor Oxnard, CA 93036 I. Introductions II. Approve Agenda III. Minutes IV. Medical Issues A. Policy 705.08: Cardiac Arrest-VF/VT B. Policy 705:09: Chest Pain C. Policy 705.25: Ventricular Tachycardia D. Policy 705.10: Childbirth E. Policy 507: Critical Care Transports F. Policy 732: Use of Restraints I. Other V. New Business A. Stroke System B. Other VI Old Business A. Impedance Threshold Device/King Airway Study Report– D. Chase B. Other VII. Informational Topics A. Pharmacology Manual B. Other VIII. Policies for Review A. Policy 210: Child, Dependent Adult, or Elder Abuse Reporting B. Policy 400: Ventura County Emergency Departments C. Policy 605: Interfacility Transfer of Patients D. Policy 606: Withholding or Termination of Resuscitation and Determination of Death E. Policy 620: EMT Administration of Oral Glucose F. Policy 624: Patient Medications G. Policy 716: Use of Pre-Existing Vascular Access Devices H. Policy 717: Intralingual Injection – Possible deletion I. Policy 723: Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) J. Policy 725: Patients after TASER Use K. Other IX. Reports TAG Report X. Agency Reports A. ALS Providers B. BLS Providers C. Base Hospitals D. Receiving Hospitals E. ALS Education Programs F. Trauma System Report G. EMS Agency H. Other XI. Closing TEMPORARY PARKING PASS Expires August 11, 2011 Health Care Services 2240 E. Gonzales Rd Oxnard, CA 93036 For use in "Green Permit Parking" Areas only, EXCLUDES Patient parking areas Parking Instructions: Parking at workshop venue is limited. -

Family Presence During Pediatric Tracheal Intubations

Supplementary Online Content Sanders RC Jr, Nett ST, Davis KF, et al; National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS) Investigators; Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Family presence during pediatric tracheal intubations. JAMA Pediatr. Published online March 7, 2016. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4627. eAppendix. Data Collection Form Used for the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS), Version 7. November 24, 2015 This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/29/2021 [Please place patient sticker here] NEAR4KIDS QI Collection Form ENCOUNTER INFORMATION Encounter #: Patient Information □ Airway Bundle Complete Date: Patient Initials: (for QI purpose only) Time: Patient Age: y m Location: Patient Dosing Weight (kg): # of Courses: Patient Gender: M F NIV/CPAP/HFNC used immediately prior to intubation: YES / NO Form Completed by (please print): Pager #: Intubated by (please print): Pager #: INDICATIONS INITIAL INTUBATION CHANGE-OF-TUBE Check as many as apply: Type of Change: Oxygen Failure From: Oral Nasal Tracheostomy (e.g. PaO2 <60 mmHg in FiO2 >0.6 in absence of cyanotic To: Oral Nasal Tracheostomy heart disease) Nature of Change: Procedure Clinical Condition (e.g. IR or MRI) Immediate after Previous Intubation (Exclude Ventilation Failure routine Trach Change) (e.g. PaCO2 > 50 mmHg in the absence of chronic lung disease) Check as many as apply: Frequent Apnea and Bradycardia Upper Airway obstruction Tube too small Therapeutic hyperventilation Tube too big (e.g. intracranial hypertension, pulmonary hypertension) Tube changed to cuffed tube Pulmonary toilet Tube changed to uncuffed tube Neuromuscular weakness Previous tube blocked or defective (e.g. -

Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction Test to Diagnose Infectious Diarrhea

1368 Correspondence / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 37 (2019) 1362–1393 Table 2 Compared the Airtraq with the Macintosh laryngoscope at tracheal intubation in subgroup analysis Number of trials RR or WMD (95% CI) P-value Cochrane's Q I2 statistic, % ⁎ The success rate Total 31 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11) 0.001 108.6 72 Normal airway 18 1.02 (0.98, 1.07) 0.34 45.8 63 ⁎ Difficult airway 13 1.15 (1.07 to 1.23) 0.0002 59.4 80 ⁎ Novice 9 1.14 (1.03 to 1.27) 0.01 32.1 75 ⁎ Experience 22 1.05 (1.01 to 1.10) 0.03 76.3 72 ⁎ The intubation time Total 28 −9.66 (−13.7 to −5.62) b0.0001 1070.1 97 Normal airway 16 −2.87 (−8.00 to 2.27) 0.27 433.2 97 ⁎ Difficult airway 12 −19.6 (−26.6 to −12.6) b0.0001 451.1 98 ⁎ Novice 6 −17.3 (−28.7 to −5.99) 0.003 54.2 91 ⁎ Experience 22 −7.96 (−12.4 to −3.50) 0.0005 9998.9 98 ⁎ The glottis visualization Total 17 1.23 (1.13 to 1.33) b0.00001 79.7 80 ⁎ Normal airway 8 1.07 (1.01 to 1.15) 0.03 16.8 58 ⁎ Difficult airway 9 1.43 (1.25 to 1.63) b0.00001 31.7 75 ⁎ Novice 4 1.15 (1.01 to 1.30) 0.03 13.8 78 ⁎ Experience 13 1.26 (1.14 to 1.40) b0.0001 61.8 81 RR: relative risk, WMD: weight mean difference, CI: confidence intervals, N/A: not applicable. -

Paramedic Protocols St September 1 , 2015

Emergency Medical Services Division Paramedic Protocols st September 1 , 2015 Edward Hill Kristopher Lyon, M.D. EMS Director Medical Director Revision Listing: 08/09/2011 – Removal of the Mucosal Atomization Device (MAD) administration route for Diazepam (Valium) 08/30/2012 – Changed language in Section III to reference Patient Care Record Policy 12/14/2012- Removed Procainamide from protocols and corrected pediatric Dextrose dosage inconsistencies 02/11/2013- Chest Pain protocol (206) updated and 12-Lead EKG protocol (210) added 03/11/2013- Morphine Sulfate dosage increased to 5 mg (initial and incremental) 03/27/2013- Pitocin removed from protocols secondary to changes in basic scope of practice by EMSA 07/01/2013 – Added Lorazepam to seizure protocol Changed dose of Versed to 1mg for adult patients and 0.05mg/kg IM for pediatrics and increased Valium dose for adult to max of 30 mg, changed pediatric dose to 0.3 mg/kg. Dopamine dosage updated to consistent dosage throughout document. Morphine contraindications update for consistency throughout document. Added section 106: Destination decision algorithm 08/07/2013 – Administration route of Epinephrine for anaphylaxis and respiratory compromise changed to intramuscular 10/01/2013 – Furosemide (Lasix) medication removed from protocols 11/01/2013 – C-Spine protocol (107) added 07/01/2014- Updated pediatric medication dosages for consistency with AHA PALS. Added protocols: Neonatal Resuscitation, Apparent Life Threatening Event, Pediatric Post Resuscitation Care, Respiratory Distress-Adult, Respiratory Distress- Pediatric, Diabetic Emergency, Nausea/Vomiting. Added medication to protocols: Atrovent, Zofran, Fentanyl Updated protocols: Altered Mental Status- Changed blood sugar level from 80 to 60, Anaphylaxis and Respiratory Distress- Changed Epi IM dose to 0.3mg, Gastric Decontamination changed to Poisoning Ingestion Overdose- removed gastric lavage, Seizure- Changed pediatric dose of versed to 0.2mg/kg IM every 10-15 min with Max dose of 6mg. -

Guidelines for Burn Care Under Austere Conditions: Introduction to Burn Disaster, Airway and Ventilator Management, and Fluid Resuscitation

SUMMARY ARTICLE Guidelines for Burn Care Under Austere Conditions: Introduction to Burn Disaster, Airway and Ventilator Management, and Fluid Resuscitation Randy D. Kearns, DHA, MSA, CEM,* Kathe M. Conlon, BSN, RN, MSHS,† Annette F. Matherly, RN, CCRN,‡ Kevin K. Chung, MD,§ Vikhyat S. Bebarta, MD,§ Jacob J. Hansen, DO,§ Leopoldo C. Cancio, MD,§ Michael Peck, MD, ScD, FACS║, Tina L. Palmieri, MD, FACS, FCCM¶ (J Burn Care Res 2016;37:e427–e439) All disasters are local, and a burn mass casualty incident have saved far more lives than were lost in the event. (BMCI) is no different. During the past 150 years, Despite improved technology and building codes, burn disasters have typically been associated with fires involving entertainment-based mass gatherings three factors: a fire/explosion in a mass gathering, continue to occur, including the Volendam Café Fire natural disaster, or act of war/terrorism. Although in the Netherlands (2001) the Rhode Island Station the incidence of fire/explosion disasters has decreased Night Club Fire (2003), and the Kiss Night Club during the past 50 years, recent natural disasters and Fire (2013) in Santa Maria, Brazil.3–5 Each of these acts of war/terrorism highlight the need for ongoing disasters left >100 dead and burned. Burn disasters preparedness.1 The goal of this missive is to provide are not limited to fires in structures, however. Nat- a background for disaster preparedness and a frame- ural disasters (Haiti Earthquake-2010, Great East work for initial assessment in a burn mass casualty. Japan Earthquake-2011) and war/terrorism (9/11 J Burn Care Res attacks-2001, Madrid Train Bombing-2004, and Historical Disasters London Subway/Bus Bombings-2005) emphasize 6–13 The Cocoanut Grove Night Club Fire (1942) in Bos- the need for broad-based disaster preparedness. -

The Use of Airtraq Laryngoscope Versus Macintosh Laryngoscope and Fiberoptic Bronchoscope by Experienced Anesthesiologists

THE USE OF AIRTRAQ LARYNGOSCOPE VERSUS MACINTOSH LARYNGOSCOPE AND FIBEROPTIC BRONCHOSCOPE BY EXPERIENCED ANESTHESIOLOGISTS KEMAL T. SARACOGLU*, MURAT ACAREL**, TUMAY UMUROGLU*** AND FEVZI Y. GOGUS**** Abstract Objective: The aim was to compare the hemodynamic parameters, intubation times, upper airway trauma and postoperative sore throat scores of the patients with normal airway anatomy, intubated with the Airtraq, Macintosh laryngoscope and fiberoptic bronchoscope, by experienced anesthesiologists. Methods: Ninety patients, scheduled to undergo elective surgery under general anesthesia were randomly divided into three groups (n=30): Group A: Airtraq laryngoscope, Group M: Macintosh laryngoscope and Group FB: fiberoptic bronchoscope. The time to intubation and success rates were recorded. The hemodynamic parameters before and one minute after the anesthesia induction were recorded and the measurements were repeated 3, 4 and 5 minutes after the endotracheal intubation. The postoperative sore throat scores and signs of any trauma were also recorded. Results: Mean arterial blood pressure and heart rate were not significantly different between the three groups. The mean intubation time interval did not differ between groups. Highest postoperative sore throat scores were recorded at the 6th hour post extubation. The scores were 37.6 ± 20.9 in Group A, 13.3 ± 16.8 in Group M and 13.6 ± 14.0 in Group FB. The scores in Group A were significantly higher compared to other groups. The number of patients requiring additional analgesia to relieve sore throat was also significantly higher in GroupA. Conclusion: The Airtraq laryngoscope seems to be a more traumatic airway device in the routine endotracheal intubation compared to Macintosh laryngoscope and fiberoptic bronchoscope, when used by experienced anesthesiologists. -

LUCAS® Chest Compression System

LUCAS Bibliography ® LUCAS CHEST COMPRESSION SYSTEM Selected Bibliography Summaries June 2016 Prehospital Studies Studies with Control Groups Rubertsson S, Lindgren E, Smekal D, et al. Per-protocol and pre-defined population analysis of the LINC study. Resuscitation. 2015;96:92-99. This study performed two pre-defined sub-group analyses within the large randomized controlled European LINC trial to evaluate if the results supported the previously reported intention to treat (ITT) analysis; the rationale being to see if results were consistent when excluding possible protocol violations and factors with estimated dismal influence on both treatment interventions tested in the randomized ITT groups (n = 2589). These sub-groups were predefined in an effort to reduce bias and the negative effects of subgroup analyses decided upon after the completion of the study. The pre-protocol group (n = 2370) excluded patients that violated the inclusion/exclusion criteria or did not get the actual treatment to which they were randomized. The pre-defined group (n = 1133) excluded patients in which the time from dispatch to arrival at the scene exceeded 12 minutes, non-witnessed cardiac arrests and in cases where the LUCAS device was not immediately brought to the scene. Patient 4-hour survival was 23.8% in the mechanical-CPR group versus 23.5% in the manual-CPR group in the per-protocol population and 31% versus 33.9% in the pre-defined group. There was no difference in any of the second outcome variables analyzed. 6 month survival with CPC score 1 (best neurological outcome) was 8.3% in the mechanical CPR group vs. -

Airway Management in Severe Post-Burn

Brief Communications Airway management in severe post-burn contracture of the neck using Airtraq: A case series INTRODUCTION Burns due to a variety of reasons are an important medico-social issue in developing countries, including India. Patients with chronic contracture of the neck and face following burns are among the most common patients visiting plastic and cosmetic surgery clinics in our hospital for reconstruction procedures. The airway management in these patients Figure 1: Photograph of the patient showing severe post‑burn contracture of the neck is difficult and challenging because of restricted neck movements and reduced mouth opening due to this Table 1: Patient demographic and airway assessment data fixed flexion deformity of the neck. Securing the Case Age ASA BMI IID MP CL CL airway in a timely and effective manner is a priority (years) physical (kg/m2) (cm) view M view A in these patients. The options are limited, and range status from awake fibreoptic to release of contractures under 1 38 I 23.76 3.8 II III I 2 44 II 21.05 2.9 III III I ketamine anaesthesia.[1] Certain newer airway devices 3 22 II 19.02 3.5 II II I are presently available and have been used to facilitate 4 23 I 23.60 3.4 III IV I airway management in difficult situations. There has 5 28 I 21.64 3.0 II IV I been no case series available on the use of Airtraq BMI – Body mass index; IID – Inter incisor distance; MP – Mallampatti class; CL view M – Cormack Lehane View with MacIntosh Blade; CL view in post-burn contractures of the neck and face. -

Is the Airtraq Optical Laryngoscope Effective in Tracheal Intubation by Novice Personnel?

Korean J Anesthesiol 2010 July 59(1): 17-21 Clinical Research Article DOI: 10.4097/kjae.2010.59.1.17 Is the Airtraq optical laryngoscope effective in tracheal intubation by novice personnel? Sang-Jin Park, Won Ki Lee, and Deok Hee Lee Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, College of Medicine, Yeungnam University, Daegu, Korea Background: Macintosh laryngoscopic intubation is a lifesaving procedure, but a difficult skill to learn. The Airtraq optical laryngoscope (AOL) is a novel intubation device with advantages over the direct laryngoscope for untrained personnel in a manikin study. We compared the effectiveness of AOL with Macintosh laryngoscope for tracheal intubation by novice personnel. Methods: We selected 37 medical students with no prior tracheal intubation experience and educated them on using both laryngoscopes. Seventy-four patients were randomly divided into two groups (group A: AOL, group M: Macintosh laryngoscope). We recorded the tracheal intubation success rate, intubation time, number of attempts, intubation difficulty scale, and adverse effects. Results: The total success rate was similar in the two groups, but the success rate at first attempt was higher in group A (P < 0.01). Group A also showed reduced duration and attempts at intubation, as well as adverse effects such as oral cavity injury. Additionally, participant reports indicated that using the AOL was easier than the Macintosh laryngoscope (P < 0.01). Conclusions: The AOL is a more effective instrument for tracheal intubation than Macintosh laryngoscope when used by novice personnel. (Korean J Anesthesiol 2010; 59: 17-21) Key Words: Airtraq optical laryngoscope, Intubation, Macintosh laryngoscope. Received: March 24, 2010.