DAN O'bannon's DYNAMIC STRUCTURE: a Course Outline for Instructors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Hero Reborn Alicia Vikander Talks Tomb Raider

MARCH/APRIL 2018 | VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 3 A HERO REBORN ALICIA VIKANDER TALKS TOMB RAIDER Inside JAMES MCAVOY KATE MARA PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 41619533 THE NINE MUST-SEE MOVIES OUT THIS SPRING & SUMMER, PAGE 38 CONTENTS MARCH/APRIL 2018 | VOL 19 | Nº3 COVER STORY 34 GAME ON! Oscar-winning actor Alicia Vikander unleashes her inner action hero to portray Lara Croft in Tomb Raider, the reboot of the videogame- based adventure series. Here the Swedish talent talks about her love of adventure movies and how her training as a ballerina helped prepare her for the physically demanding role BY MARNI WEISZ REGULARS 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 6 SNAPS 8 IN BRIEF 16 ALL DRESSED UP 18 IN THEATRES 44 RETURN ENGAGEMENT 46 CINEPLEX STORE 50 FINALLY… FEATURES BROS. PICTURES FRANK OCKENFELS/WARNER BY PHOTO COVER 14 HORSE POWER 28 COVER UP 32 LOVER & FIGHTER 38 MOVIE PREVIEW! Canadian Ajuawak Kapashesit Kate Mara talks about The star of Submergence, Nine must-see movies explains how The Revenant playing Mary Jo Kopechne, James McAvoy, reveals what hitting screens in May, steered him into acting and his the woman at the centre of it’s like to play a smitten lover June and July, beginning eventual part in this month’s Chappaquiddick’s scandalous, and a torture victim in the with the star-studded Marvel Indian Horse real-life tragedy same film pic Avengers: Infinity War BY INGRID RANDOJA BY BOB STRAUSS BY INGRID RANDOJA BY MARNI WEISZ MARCH/APRIL 2018 | CINEPLEX MAGAZINE | 3 EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHER SALAH BACHIR EDITOR MARNI WEISZ DEPUTY EDITOR INGRID RANDOJA CREATIVE DIRECTOR LUCINDA WALLACE GRAPHIC DESIGNER DARRYL MABEY VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION SHEILA GREGORY CONTRIBUTORS BOB STRAUSS ADVERTISING SALES FOR CINEPLEX MAGAZINE AND LE MAGAZINE CINEPLEX IS HANDLED BY CINEPLEX MEDIA. -

An Exploration of Zombie Narratives and Unit Operations Of

Acta Ludologica 2018, Vol. 1, No. 1 ABSTRACT: This document details the abstract for a study on zombie narratives and zombies as units and their translation from cinemas to interactive mediums. Focusing on modern zombie mythos and aesthetics as major infuences in pop-culture; including videogames. The main goal of this study is to examine the applications The Infectious Aesthetic of zombie units that have their narrative roots in traditional; non-ergodic media, in videogames; how they are applied, what are their patterns, and the allure of Zombies: An Exploration of their pervasiveness. of Zombie Narratives and Unit KEY WORDS: Operations of Zombies case studies, cinema, narrative, Romero, unit operations, videogames, zombie. in Videogames “Zombies to me don’t represent anything in particular. They are a global disaster that people don’t know how to deal with. David Melhart, Haryo Pambuko Jiwandono Because we don’t know how to deal with any of the shit.” Romero, A. George David Melhart, MA University of Malta Institute of Digital Games Introduction 2080 Msida MSD Zombies are one of the more pervasive tropes of modern pop-culture. In this paper, Malta we ask the question why the zombie narrative is so infectious (pun intended) that it was [email protected] able to successfully transition from folklore to cinema to videogames. However, we wish to look beyond simple appearances and investigate the mechanisms of zombie narratives. To David Melhart, MA is a Research Support Ofcer and PhD student at the Institute of Digital do this, we employ Unit Operations, a unique framework, developed by Ian Bogost1 for the Games (IDG), University of Malta. -

Application of the Public Advocates Office for Rehearing of Resolution E

BEFORE THE PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA FILED 05/19/21 04:59 PM Application of the Public Advocates Office A2105013 for Rehearing of Resolution E-5139. A.21-05- CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify that I have on this date served a copy of APPLICATION OF THE PUBLIC ADVOCATES OFFICE FOR REHEARING OF RESOLUTION E-5139 to all known parties by either United States mail or electronic mail, to each party named on the official service list attached in R.16-02-007. An electronic copy was sent to the assigned Administrative Law Judge. Executed on May 19, 2021 at San Francisco, California. /s/ Sara J. Powell Sara J. Powell 385030264 1 / 47 CPUC Home CALIFORNIA PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION Service Lists PROCEEDING: R1602007 - CPUC - OIR TO DEVELO FILER: CPUC LIST NAME: LIST LAST CHANGED: APRIL 13, 2021 Parties DAMON FRANZ DAVID LYONS DIR - POLICY & ELECTRICITY MARKETS ATTORNEY TESLA, INC. PAUL HASTINGS LLP EMAIL ONLY EMAIL ONLY EMAIL ONLY, CA 00000 EMAIL ONLY, CA 00000 FOR: TESLA, INC. (FORMERLY: SOLARCITY FOR: LA PALOMA GENERATING COMPANY,LLC CORPORATION) JEFFREY KEHNE JOHN W. LESLIE, ESQ. CHIEF DEVELOPMENT OFFICE / GEN.COUNSEL ATTORNEY MEGELLAN WIND LLC DENTONS US LLP EMAIL ONLY EMAIL ONLY EMAIL ONLY, DC 00000 EMAIL ONLY, CA 00000 FOR: MAGELLAN WIND LLC FOR: SHELL ENERGY NORTH AMERICA (U.S.), L.P. MATTHEW FREEDMAN MERRIAN BORGESON STAFF ATTORNEY SR. SCIENTIST THE UTILITY REFORM NETWORK NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL EMAIL ONLY EMAIL ONLY EMAIL ONLY, CA 00000 EMAIL ONLY, CA 00000 FOR: THE UTILITY REFORM NETWORK (TURN) FOR: NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL (NRDC) PETER T. -

"They're Us": Representations of Women in George Romero's 'Living

"They’re Us": Representations of Women in George Romero’s ‘Living Dead’ Series Stephen Harper In the opening scene of George Romero’s 1978 film Martin, a teenage sexual psychopath kills and drinks the blood of a young woman in her sleeper train compartment during a struggle that is protracted, messy and far from one-sided. Although women are often victims in Romero’s films, they are by no means passive ones. Indeed, Romero is seldom in danger of objectivising or pornographising his female characters; on the contrary, Romero’s women are typically resourceful and autonomous. This paper analyses some of Romero’s representations of women, with particular reference to the four ‘living dead’ films which Romero made over a period of more than thirty years. These are Night of the Living Dead (1968), Dawn of the Dead (1979), Day of the Dead (1985) and the 1990 remake of Night. [1] All of these films feature a group of human survivors in an America overrun by zombies. The survivors of Night hole up in a house; in Dawn the sanctuary is a shopping mall; while in Day, the darkest of the films, it is an underground military installation. Unsurprisingly, these savage and apocalyptic zombie films contain some of Romero’s most striking representations of active and even aggressive women. This in itself hints at a feminist approach. While Hollywood films typically eroticize and naturalise male violence and emphasise female passivity, Romero uses his zombies to undermine such assumptions. Romero’s female zombies are not only undead but virtually ungendered; for instance, they are responsible for as many acts of violence as their male counterparts. -

When Zombies Attack! Mathematical Modeling of an Outbreak Of

In: Infectious Disease Modelling Research Progress ISBN 978-1-60741-347-9 Editors: J.M. Tchuenche and C. Chiyaka, pp. 133-150 c 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 4 WHEN ZOMBIES ATTACK!: MATHEMATICAL MODELLING OF AN OUTBREAK OF ZOMBIE INFECTION Philip Munz1,∗ Ioan Hudea1,y Joe Imad2,z Robert J. Smith?3x 1School of Mathematics and Statistics, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6, Canada 2Department of Mathematics, The University of Ottawa, 585 King Edward Ave, Ottawa ON K1N 6N5, Canada 2Department of Mathematics and Faculty of Medicine, The University of Ottawa, 585 King Edward Ave, Ottawa ON K1N 6N5, Canada Abstract Zombies are a popular figure in pop culture/entertainment and they are usually portrayed as being brought about through an outbreak or epidemic. Consequently, we model a zombie attack, using biological assumptions based on popular zombie movies. We introduce a basic model for zombie infection, determine equilibria and their stability, and illustrate the outcome with numerical solutions. We then refine the model to introduce a latent period of zombification, whereby humans are infected, but not infectious, before becoming undead. We then modify the model to include the effects of possible quarantine or a cure. Finally, we examine the impact of regular, impulsive reductions in the number of zombies and derive conditions under which eradication can occur. We show that only quick, aggressive attacks can stave off the doomsday scenario: the collapse of society as zombies overtake us all. 1. Introduction A zombie is a reanimated human corpse that feeds on living human flesh [1]. -

Michał Zgorzałek* GEORGE A. ROMERO's

STUDIA HUMANISTYCZNE AGH Tom 15/2 • 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.7494/human.2016.15.2.43 Michał Zgorzałek* Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin GEORGE A. ROMERO’S DYSTOPIAS: THE REPRESENTATION OF DYSTOPIA IN THE UNIVERSE OF HIS ZOMBIE TRILOGY The present paper discusses dystopia in the genre of horror on the basis of George A. Romero’s zombie fi lms. Dystopia seems to be inextricably linked with the vision of the world in which the very structure of the society has been destroyed along with moral codes and the only remaining thing is the will to survive. In the Living Dead Trilogy Romero skilfully used the zombie apocalypse motif to portray both vices as virtues characteristic to American way of life. Moreover, in his motion pictures, he envisages what may be the implications of pos- sible dystopias arising from the ashes of destroyed human civilisation and, thus, gives the audiences, and the critics, an incredible resource for interpretation and further analysis. The methodology involves the paradigmatic analysis of the plots in order to show how the motif of zombie apocalypse is used to explore the notion of dystopia. Moreover, the mentioned analysis will also cover explicit, implicit and symptomatic meaning created by the analyzed fi lms. Keywords: dystopia, social critique, human holocaust, morality INTRODUCTION Throughout his career, George A. Romero has directed over sixteen pictures, trying his hand at such fi lm genres as the thriller, comedy, documentary and horror. And this last genre is the focus of this paper. The fi lms examined in this work are the so-called zombie movies directed, and also written, by Romero. -

Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media

Your Friendly Neighbourhood Zombie: Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media by Jessica Wind A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Jess Wind Abstract Our deepest social fears and anxieties are often communicated through the zombie, but these readings aren’t reflected in contemporary zombie media. Increasingly, we are producing a less scary, less threatening zombie — one that is simply struggling to navigate a society in which it doesn’t fit. I begin to rectify the gap between zombie scholarship and contemporary zombie media by mapping the zombie’s shift from “outbreak narratives” to normalized monsters. If the zombie no longer articulates social fears and anxieties, what purpose does it serve? Through the close examination of these “normalized” zombie media, I read the zombie as possessing a non- normative body whose lived experiences reveal and reflect tensions of identity construction — a process that is muddy, in motion, and never easy. We may be done with the uncontrollable horde, but we’re far from done with the zombie and its connection to us and society. !ii Acknowledgements I would like to start by thanking Sheryl Hamilton for going on this wild zombie-filled journey with me. You guided me as I worked through questions and gained confidence in my project. Without your endless support, thorough feedback, and shared passion for zombies it wouldn’t have been nearly as successful. Thank you for your honesty, deadlines, and coffee. I would also like to thank Irena Knezevic for being so willing and excited to read this many pages about zombies. -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: COMMUNICATING FEAR in FILM

ABSTRACT Title of Document: COMMUNICATING FEAR IN FILM MUSIC: A SOCIOPHOBIC ANALYSIS OF ZOMBIE FILM SOUNDTRACKS Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez Master of Arts, 2014 Directed By: Dr. Patrick Warfield, Musicology The horror film soundtrack is a complex web of narratological, ethnographic, and semiological factors all related to the social tensions intimated by a film. This study examines four major periods in the zombie’s film career—the Voodoo zombie of the 1930s and 1940s, the invasion narratives of the late 1960s, the post-apocalyptic survivalist fantasies of the 1970s and 1980s, and the modern post-9/11 zombie—to track how certain musical sounds and styles are indexed with the content of zombie films. Two main musical threads link the individual films’ characterization of the zombie and the setting: Othering via different types of musical exoticism, and the use of sonic excess to pronounce sociophobic themes. COMMUNICATING FEAR IN FILM MUSIC: A SOCIOPHOBIC ANALYSIS OF ZOMBIE FILM SOUNDTRACKS by Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2014 Advisory Committee: Professor Patrick Warfield, Chair Professor Richard King Professor John Lawrence Witzleben ©Copyright by Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez 2014 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS II INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 1 Introduction 1 Why Zombies? 2 Zombie Taxonomy 6 Literature Review 8 Film Music Scholarship 8 Horror Film Music Scholarship -

A Look Back Raceway, Floods, SR-36 Top List

www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELE RANSCRIPT Cowgirls clipped T by Lady Hawks in extra session See A6 BULLETIN January 3, 2006 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 112 NO. 64 50 cents 2005 A Look Back Raceway, floods, SR-36 top list When newspapers compile lists of top stories, they look to those events that impact the most people within their reader- ship areas. Such is the case with this year’s Tooele Transcript- Bulletin Top 20 stories for 2005. Business and residential devel- opers focused on Tooele County this year because the population continues to climb. It soared to an estimated 52,000 in 2005. Utah business mogul Larry H. Miller found enough open space in Tooele Valley and coopera- tion from county leaders to build his dream project. The develop- ment of Miller Motorsports Park ranked No. 1 on our list. Other growth-related stories include the completion of SR- 36 and other business projects throughout the county. The coun- ty’s ongoing negotiations with hazardous waste companies and changes soon to come to Deseret Chemical were big. Throughout the year, Utah’s leaders waged war with Private Fuel Storage in its efforts to store high-level nuclear waste in Skull Valley. Nature also played a big role this year by pounding Tooele with its biggest rainstorm ever. photography / Troy Boman Miller Motorsports Park earned the pole position in our list The deluge added to the wet of top 20 stories of 2005. Larry H. Miller (left) sits in one year overall, ending six years of of his restored and race-ready Ford Cobras. -

LCCC Thematic List

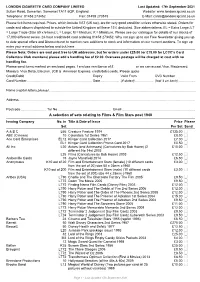

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

Andamios 259 Alma Delia Zamorano Rojas* Hemos Arribado Al Siglo XXI En Medio De Profundas Transformaciones En Todos Los Campos D

ASESINOS POR NATURALEZA: UNA LECTURA PRIMIGENIA DE LA VIOLENCIA EN EL CINE Alma Delia Zamorano Rojas* RESUMEN. El artículo analiza el problema de la violencia desde una de las respuestas que le ha dado la sociedad contemporánea: sirviéndose del filme de Oliver Stone, paradigmático en el tra tamiento de la agresión y la violencia. La autora analiza el tema, ensayando respuestas ante tópicos que van desde su cauce me diático y su trivialización, hasta sus alcances como crítica del poder. La investigación exhibe un recuento de causas que jus tifican el tratamiento de la violencia como una crítica fílmica de la percepción posmoderna de la realidad: ante la crisis del espíritu, la ciencia y la verdad. PALABRAS CLAVE. Posmodernidad, violencia, agresión, cine, Oliver Stone. HACIA UNA CONCEPTUALIZACIÓN DE CINE POSMODERNO Hemos arribado al siglo XXI en medio de profundas transformaciones en todos los campos de la cultura, habitamos un mundo centrado en la informática, regido por los medios de comunicación y basado en la lógica del consumo. La aceleración de los tiempos y sus cambios ver tiginosos acentúan la sensación de estar frente a una mutación social global cuyos alcances aún no nos resultan ni medianamente accesibles. Aunado a ello, los descubrimientos en la ciencia y la técnica, en su interacción recíproca y en sus secuelas sobre el modo de producción, así como las formas organizativas de la sociedad y los innovadores * Doctora en ciencias políticas y sociales por la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Profesorainvestigadora de tiempo completo en la Universidad Pana mericana. Correo electrónico: [email protected] Volumen 10, número 22, mayoagosto, 2013, pp.