The Roadrunner in Fact and Folk-Lore 13 3 James T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Kit | Expansion 2022

PRESS KIT | EXPANSION 2022 1 CONTENTS HISTORY OF EXCELLENCE ............................. 2 WAC DIGITAL NETWORK ................................ 4 OUR FUTURE BEGINS TODAY ......................... 6 2022-23 WAC MEMBERS ................................ 8 WAC MEN’S SPORTS ..................................... 15 WAC WOMEN’S SPORTS ............................... 16 2022-23 WAC NAMING GUIDE ...................... 17 SHARE THE EXCITEMENT OF THE WAC WITH YOUR COMMUNITY ............ 18 A TIMELINE OF ACCOMPLISHMENTS .......... 20 CONTACTS ..................................................... 22 1 A HISTORY OF EXCELLENCE FIVE GENERATIONS OF SUCCESS CONTINUED COMMITMENT TO ACHIEVEMENT After completing its 58th year of intercollegiate The WAC has experienced tremendous success over the competition, the Western Athletic Conference continues to years. In men’s basketball, the WAC has sent at least evolve and feature some of the nation’s best programs. One two teams to the NCAA Tournament in 28 of the past thing that remains unchanged is the persistent nature of 45 seasons. In baseball, the WAC has boasted two WAC’s student-athletes work to the institutions in the WAC to advance their programs and national champions since 2003. In women’s basketball, contend at the top levels of the NCAA. the conference has had at least two teams qualify for the achieve the highest levels of success NCAA Tournament 10 times in 28 seasons, with a record with the academic support of their The WAC provides its student-athletes the chance to travel five teams in 1998. The WAC also sent teams to three BCS to scenic destinations and gain exposure in some of the football bowl games from 2007-10. respective institutions. nation’s most diverse markets and largest metropolitan cities. In addition, the WAC’s student-athletes work to achieve the highest levels of success with the academic support of their respective institutions. -

The Developmental Process of the Thread That Snapped

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Theses Theses and Dissertations 9-1-2020 DIVING INTO ONE’S PAINFUL PAST AND DARKEST INTERNAL FEARS: THE DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESS OF THE THREAD THAT SNAPPED Austin Brian Harrison Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Harrison, Austin Brian, "DIVING INTO ONE’S PAINFUL PAST AND DARKEST INTERNAL FEARS: THE DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESS OF THE THREAD THAT SNAPPED" (2020). Theses. 2732. https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/theses/2732 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIVING INTO ONE’S PAINFUL PAST AND DARKEST INTERNAL FEARS: THE DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESS OF THE THREAD THAT SNAPPED by Austin Harrison M.A., Louisiana Tech University, 2017 B.S., Louisiana Tech University, 2015 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Fine Arts Degree Department of Theatre in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2020 Copyright by Austin Harrison, 2020 All Rights Reserved THESIS APPROVAL DIVING INTO ONE’S PAINFUL PAST AND DARKEST INTERNAL FEARS: THE DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESS OF THE THREAD THAT SNAPPED by Austin Harrison A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in the field of Theatre Approved by: Dr. Jacob Juntunen, Chair Mark Varns Segun Ojewuyi Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 10, 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Austin Harrison, for the Master of Fine Arts degree in Theatre, presented on April 10, 2020, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

American Indian Law Journal

American Indian Law Journal Volume III, Issue II • Spring 2015 “The Spirit of Justice” by Artist Terrance Guardipee Supported by the Center for Indian Law & Policy SPIRIT OF JUSTICE Terrence Guardipee and Catherine Black Horse donated this original work of art to the Center for Indian Law and Policy in November 2012 in appreciation for the work the Center engages in on behalf of Indian and Native peoples throughout the United States, including educating and training a new generation of lawyers to carry on the struggle for justice. The piece was created by Mr. Guardipee, who is from the Blackfeet Tribe in Montana and is known all over the country and internationally for his amazing ledger map collage paintings and other works of art. He was among the very first artists to revive the ledger art tradition and in the process has made it into his own map collage concept. These works of art incorporate traditional Blackfeet images into Mr. Guardipee’s contemporary form of ledger art. He attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Sante Fe, New Mexico. His work has won top awards at the Santa Fe Market, the Heard Museum Indian Market, and the Autrey Museum Intertribal Market Place. He also has been featured a featured artists at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., along with the Museum of Natural History in Hanover, Germany, and the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College. American Indian Law Journal Editorial Board 2014-2015 Editor-in-Chief Jocelyn McCurtain Managing Editor Callie Tift Content Editor Executive Editor Jillian Held Nancy Mendez Articles Editors Writing Competition Chair Events Coordinator Jessica Buckelew Nick Major Leticia Hernandez Jonathan Litner 2L Staffers Paul Barrera - Jessica Barry J. -

City Secretary City of Amarillo, Texas

CITY SECRETARY CITY OF AMARILLO, TEXAS EXECUTIVE SEARCH PROVIDE BY The Community marillo sits at the crossroads of America, almost equidistant from both coasts, with a population of 199,000 Aresidents and covering 100 square miles. Amarillo is the 14th largest city in Texas in terms of population. Located in Potter and Randall counties in the Texas Panhandle, it is the county seat of Potter County. Amarillo is situated at the intersection of Interstate 40 and Interstate 27, approximately 120 miles north of Lubbock, 360 miles northwest of Dallas-Fort Worth, and centered approximately 275 miles from both Albuquerque and Oklahoma City. The City of Amarillo and the associated region have a quality of life that makes living and working in the area very attractive. Amarillo has an ample workforce and low property taxes. Amarillo is the regional center for emergency management and homeland security coordination, hospitals, medical facilities, higher education, shopping, and entertainment for the 26 counties of the upper Panhandle of Texas and communities in Oklahoma, New Mexico, and southern portions of Kansas and Colorado. Amarillo has a diversified economy. Two mainlines of the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway intersect at Amarillo and provide direct service to 11 major locations. Local businesses and industries include energy research and development, beef processing, agriculture, copper refining, wholesale distribution, fiberglass production, defense contracting, aviation assembly and maintenance, metal machining and finishing, and oil and gas production. The medical community is very important to the Amarillo economy. Texas Tech Health Sciences Center, located in Amarillo, has a consolidated 20-acre medical center comprising the schools of medicine, pharmacy, and allied health. -

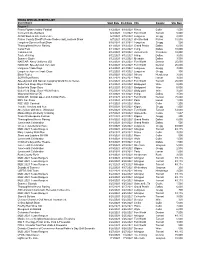

EMPLOYERS RECRUITED by EMPLOYER RELATIONS COORDINATOR a to Z Tire AAA of Texas – 2X Academy Sports Adequan Affiliated Foods A

EMPLOYERS RECRUITED BY EMPLOYER RELATIONS COORDINATOR A to Z Tire Childress Regional Medical Center AAA of Texas – 2X CHS Lubricants Academy Sports Cimarron Feeders Adequan Cintas -5X Affiliated Foods – 2X Cisco Systems Alstom Power City of Midland Alvey Law & Tax Service City of Midland Parks and Recreation Ama Techtel Communications – 2X Claude ISD Amarillo Chamber of Commerce Coca-Cola of Amarillo – 4X Amarillo Country CLub Collingsworth General Hospital – 2X Amarillo Gear Conoco Phillips – 3X Amarillo Grain Exchange Country Barn Steak House Amarillo ISD - 2X Covenant Health Systems Amarillo National Bank Crop Production Services Amarillo Town Club – 2X CrownQuest Operating – 2X Amarillo VA Health System – 2X Cudd Energy Services – 2X Americold Logistics Dallam Hartley County Hospital American Quarter Horse Association Dallas Area Rapid Transit Police Department American Tire Distributors DeBruce Grain – 3X Andrews ISD Dillards – 6X ASARCO Dirkson Buildings Asco Downtown Athletic Club Athletic Edge Dumas ISD Atmos Energy – 3X Education Credit Union -4X Attebury Grain Edward Jones B&W Pantex – 5X Enterprise Rent-A-Car – 2X Baldwin Distribution Ernst & Young Bank of Commerce Excel Manufacturing Baptist Community Services – 2X Exterran Bar S Feeds Farnum Basic Energy Services – 2X Fidelity Investments – 3X Beef Products Inc – 2X Financial Freedom and Futures Bell Helicopter – 3X First Bank Southwest – 5X Ben E Keith Foods – 3X First Capital Bank Big Texas Steak House First United Bank BJ Services Floydada ISD BNSF Friona Feedyards Borger -

Texas-Special-Events

TEXAS SPECIAL EVENTS LIST Event Name Start Date End Date City County Site Size Region 1 Frisco Fighters Indoor Football 3/12/2021 6/19/2021 Frisco Collin 1,500 Concert in the Gardens 6/4/2021 7/4/2021 Fort Worth Tarrant 5,000 ACSD Student Life Conference 6/7/2021 6/10/2021 Longview Gregg 2,000 Parker County Sheriff's Posse Rodeo and Livestock Show 6/7/2021 6/12/2021 Weatherford Parker 10,000 Longview Summer Boat Show 6/10/2021 6/13/2021 Longview Gregg 500 Thoroughbred Horse Racing 6/11/2021 6/13/2021 Grand Prairie Dallas 6,000 Canal Fest 6/11/2021 6/12/2021 Irving Dallas 10,000 Tomato Fest 6/12/2021 6/19/2021 Jacksonville Cherokee 10,000 Taste of Irving 6/12/2021 6/12/2021 Irving Dallas 3,000 Summer Sizzle 6/12/2021 6/12/2021 Mesquite Dallas 3,500 NASCAR: Alsco Uniforms 250 6/12/2021 6/12/2021 Fort Worth Denton 25,000 NASCAR: SpeedyCash.com 220 6/12/2021 6/12/2021 Fort Worth Denton 25,000 Longview Trade Days 6/12/2021 6/13/2021 Longview Gregg 3,000 Longview Jaycees Trade Days 6/12/2021 6/13/2021 Longview Gregg 300 Black Rodeo 6/12/2021 6/12/2021 Athens Henderson 3,000 SOBA Boat Races 6/12/2021 6/14/2021 Paris Lamar 3,000 SpeedyCash 400 Nascar Camping World Truck Series 6/12/2021 6/12/2021 Fort Worth Tarrant 25,000 Butterfield Stage Days Parade 6/12/2021 6/12/2021 Bridgeport Wise 8,000 Butterfield Stage Days 6/12/2021 6/12/2021 Bridgeport Wise 6,500 Butterfield Stage Days PRCA Rodeo 6/12/2021 6/12/2021 Bridgeport Wise 3,500 Wounded Warrior 5K 6/13/2021 6/13/2021 Irving Dallas 3,500 NASCAR: All-Star Open and All-Star Race 6/13/2021 6/13/2021 -

2015 UTSA Roadrunners Football Media Supplement Table of Contents

2015 UTSA ROADRUNNERS FOOTBALL MEDIA SUPPLEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION Lynn Hickey ______________________________________ 46 Quick Facts _______________________________________ 2 Dr. Ricardo Romo _________________________________ 47 Schedule __________________________________________ 2 NCAA Compliance ________________________________ 48 Timeline __________________________________________ 3 Future Schedules ___________________________________ 3 PLAYERS Athletics Communications Staff _______________________ 4 Player Bios ____________________________________ 50-68 Media Policy _____________________________________4-5 Alamodome Directions & Parking _____________________ 6 SEASON REVIEW Local Media Directory ______________________________ 7 Individual Honors _________________________________ 70 Roadrunners Sports Network _________________________ 7 Schedule/Results __________________________________ 71 Opponents Quick Facts ____________________________8-9 Team Statistics ____________________________________ 71 Conference USA _______________________________ 10-11 Record Breakdown ________________________________ 71 Conference USA Composite Schedule ________________ 12 UTSA Game-by-Game Statistics _____________________ 72 Conference USA Championship Game _______________ 13 Opponent Game-by-Game Statistics _________________ 73 Bowl Synopsis _________________________________ 14-16 Individual Statistics _____________________________ 74-75 Starters Summary _________________________________ 75 SEASON OUTLOOK Defensive Statistics ________________________________ -

Bandits Football Career Team Game Records

Bandits Football Career Team Game Records Most carries Most rushing TDs scored 1. 42 - Fairbanks Grizzlies; 6/13/2009 1. 7 - Amarillo Venom; 6/13/2015 2. 38 - at Dodge City Law; 6/6/2015 7 - Evansville Bluecats; 6/18/2005 3. 37 - Sioux Falls Storm; 8/14/2005 7 - at Johnstown Jackyls; 5/20/2000 37 - Bloomington Edge; 6/8/2013 4. 6 - Springfield Wolfpack; 4/28/2012 5. 36 - at Peoria Roughriders; 6/3/2006 6 - at Erie; 7/8/2000 6. 35 - Sioux Falls Storm; 7/15/2005 6 - at LINCOLN LIGHTNING; 7/15/2000 35 - at Sioux Falls Storm; 6/9/2001 6 - at Dodge City Law; 6/6/2015 35 - Texas Revolution; 6/20/2015 6 - at Kansas Koyotes; 6/1/2013 35 - at River City Rage; 6/21/2008 6 - Salina Bombers; 6/14/2014 10. 34 - at Omaha Beef; 4/24/2015 6 - Texas Revolution; 6/20/2015 34 - Tenn. Valley Raptors; 8/6/2005 6 - at Springfield Wolfpack; 3/31/2012 12. 33 - at Omaha Beef; 4/22/2006 6 - Omaha Beef; 5/10/2014 33 - Billings; 6/2/2001 6 - Omaha Beef; 5/16/2015 33 - at Sioux Falls Storm; 6/25/2005 14. 5 - at Omaha Beef; 4/9/2005 33 - at Kansas Koyotes; 5/24/2014 5 - Colorado Lightning; 4/14/2012 5 - Wichita Warlords; 4/21/2000 Most net yards rushing 5 - Peoria Rough Riders; 4/23/2005 1. 238 - Bloomington Edge; 6/8/2013 5 - at Black Hills Red Dogs; 4/30/2005 2. 216 - at River City Rage; 6/21/2008 5 - Omaha Beef; 2/28/2015 3. -

Texas A&M-Kingsville Javelinas

2018 DIGITAL PROGRAM Lone Star Conference Basketball Championship | March 1-4, 2018 Dear Basketball Fans, Thank you for attending the 2018 Lone Star Conference Men’s and Women’s Basketball Championship. We’re excited to partner with Visit Frisco and Dr Pepper Arena to bring LSC basketball to Frisco, home of the Dallas Stars, Dallas Cowboys, FC Dallas, the Texas Legends and now…the LSC! With 11 member institutions in Texas, New Mexico and Oklahoma, the LSC seeks to provide student-athletes with a first-class experience. We believe the LSC Basketball Championship does just that, while highlighting the outstanding basketball being played in our Conference and giving our member schools a chance to reconnect with former students and recruit future students in the North Texas area. I hope you will have a great time and enjoy the games this week. As you cheer on your favorite team, I request your assistance in helping to create a positive game environment for all attendees. I encourage enthusiastic support for your team, but I also ask that you respect all participants by treating players, coaches, officials and fellow fans with respect. Thank you for your support in creating a great championship experience for our student-athletes. Enjoy the games! Respectfully, Jay Poerner @LoneStarConf | #LSCmbb | #LSCwbb 3 Lone Star Conference Basketball Championship | March 1-4, 2018 LONE Star CONFERENCE Long known as a leader in intercollegiate athletics, the Lone Star Conference™ (LSC) is an innovative athletics conference that aims to provide a superior competitive experience for member institutions and to allow for comprehensive development of student-athletes through academic services and life skills programming. -

Elizabeth A. Schor Collection, 1909-1995, Undated

Archives & Special Collections UA1983.25, UA1995.20 Elizabeth A. Schor Collection Dates: 1909-1995, Undated Creator: Schor, Elizabeth Extent: 15 linear feet Level of description: Folder Processor & date: Matthew Norgard, June 2017 Administration Information Restrictions: None Copyright: Consult archivist for information Citation: Loyola University Chicago. Archives & Special Collections. Elizabeth A. Schor Collection, 1909-1995, Undated. Box #, Folder #. Provenance: The collection was donated by Elizabeth A. Schor in 1983 and 1995. Separations: None See Also: Melville Steinfels, Martin J. Svaglic, PhD, papers, Carrigan Collection, McEnany collection, Autograph Collection, Kunis Collection, Stagebill Collection, Geary Collection, Anderson Collection, Biographical Sketch Elizabeth A. Schor was a staff member at the Cudahy Library at Loyola University Chicago before retiring. Scope and Content The Elizabeth A. Schor Collection consists of 15 linear feet spanning the years 1909- 1995 and includes playbills, catalogues, newspapers, pamphlets, and an advertisement for a ticket office, art shows, and films. Playbills are from theatres from around the world but the majority of the collection comes from Chicago and New York. Other playbills are from Venice, London, Mexico City and Canada. Languages found in the collection include English, Spanish, and Italian. Series are arranged alphabetically by city and venue. The performances are then arranged within the venues chronologically and finally alphabetically if a venue hosted multiple productions within a given year. Series Series 1: Chicago and Illinois 1909-1995, Undated. Boxes 1-13 This series contains playbills and a theatre guide from musicals, plays and symphony performances from Chicago and other cities in Illinois. Cities include Evanston, Peoria, Lake Forest, Arlington Heights, and Lincolnshire. -

Chadron State.Indd

22012012 WWestest TTexasexas AA&M&M GGameame NNotesotes 22012012 WWestest TTexasexas AA&M&M BBuffalouffalo FFootballootball LLSCSC CHHAMPIONSAMPIONS • 11986986 • 22005005 • 22006006 • 22007007 • 22012012 NNCAACAA PLLAYOFFAYOFF APPPEARANCESPEARANCES 22005005 • 22006006 • 22007007 • 22008008 • 22010010 • 22012012 Kit Strief • West Texas A&M Assistant A.D. for Media Relations Offi ce • 806.651.4430 | Cell • 515.490.4627 | Fax • 806.651.4409 Email • [email protected] | www.GoBuffsGo.com GGameame DDayay IInformationnformation GAAMEME 1122 - ##1616 WEESTST TEEXASXAS AA&M&M AATT ##2020 CHHADRONADRON STTATEATE - SAATT..,, NOOVV. 117,7, 22012012 Date: Saturday, November 17, 2012 Kickoff: 1 p.m. CT No. 6-Seed West Texas A&M Buffaloes No. 3-Seed Chadron State Eaglesg Location: Chadron, Neb. 2012 Record (LSC): 9-2 (7-1) 2012 Record (RMAC): 9-2 (8-1) Stadium: Elliott Field at Don Beebe Stadium Head Coach: Don Carthel Head Coach: Jay Long Capacity: 3,800 Career Record: 122-67-1 Career Record: 24-17 (4th season) Television: KCIT FOX-TV WTAMU Record: 76-21 Chadron State Record: 9-2 Radio: KGNC-710 AM 2012 Leaders: 2012 Leaders: Internet Streaming/Stats: www.gobuffsgo.com Dustin Vaughan (JR-QB, 260-401-7, 35 TD, 3552 Yds) G. Clinton (RB, 208 att., 1302 Yds., 7 TD, 118.4 Ypg.) Series: Chadron State leads 1-0 Torrence Allen (JR-WR, 49 Rec., 966 Yds, 9 TD) J. McLain (QB, 207-313-6, 28 TD, 2275 Yds, 206.8 Ypg.) Last Meeting: CSC 43-17, Nov. 25, 2006 (A) Khiry Robinson (SR-RB, 134 att., 1015 Yds, 11 TD) N. Ross (WR, 46 Rec., 729 Yds, 9 TD, 66.3 Ypg.) Taylor McCuller (JR-LB, 118 Tackles, 3.5 Sacks, 8.0 TFL) K. -

Historical Theater Programs Collection MS-87 Wright State

Historical Theater Programs Collection (MS-87) Guide This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 21, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Wright State University Libraries, Special Collections and Archives Special Collections and Archives 3640 Colonel Glenn Hwy Dayton, OH 45435-0001 [email protected] URL: http://www.libraries.wright.edu/special Historical Theater Programs Collection (MS-87) Guide Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents ...................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement ............................................................... .................................................................. 3 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................... 4 Collection Inventory ............................................................... ...................................................... 4 Series 1: Plays and Musicals ............................................................... ....................................... 4 Series 2: Animal Shows & Races ............................................................................................. 29 Series 3: Concerts ............................................................... .....................................................