A Type Theory for Memory Allocation and Data Layout ∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECSS-E-TM-40-07 Volume 2A 25 January 2011

ECSS-E-TM-40-07 Volume 2A 25 January 2011 Space engineering Simulation modelling platform - Volume 2: Metamodel ECSS Secretariat ESA-ESTEC Requirements & Standards Division Noordwijk, The Netherlands ECSS‐E‐TM‐40‐07 Volume 2A 25 January 2011 Foreword This document is one of the series of ECSS Technical Memoranda. Its Technical Memorandum status indicates that it is a non‐normative document providing useful information to the space systems developers’ community on a specific subject. It is made available to record and present non‐normative data, which are not relevant for a Standard or a Handbook. Note that these data are non‐normative even if expressed in the language normally used for requirements. Therefore, a Technical Memorandum is not considered by ECSS as suitable for direct use in Invitation To Tender (ITT) or business agreements for space systems development. Disclaimer ECSS does not provide any warranty whatsoever, whether expressed, implied, or statutory, including, but not limited to, any warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose or any warranty that the contents of the item are error‐free. In no respect shall ECSS incur any liability for any damages, including, but not limited to, direct, indirect, special, or consequential damages arising out of, resulting from, or in any way connected to the use of this document, whether or not based upon warranty, business agreement, tort, or otherwise; whether or not injury was sustained by persons or property or otherwise; and whether or not loss was sustained from, or arose out of, the results of, the item, or any services that may be provided by ECSS. -

CSE 220: Systems Programming

Memory Allocation CSE 220: Systems Programming Ethan Blanton Department of Computer Science and Engineering University at Buffalo Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary Allocating Memory We have seen how to use pointers to address: An existing variable An array element from a string or array constant This lecture will discuss requesting memory from the system. © 2021 Ethan Blanton / CSE 220: Systems Programming 2 Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary Memory Lifetime All variables we have seen so far have well-defined lifetime: They persist for the entire life of the program They persist for the duration of a single function call Sometimes we need programmer-controlled lifetime. © 2021 Ethan Blanton / CSE 220: Systems Programming 3 Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary Examples int global ; /* Lifetime of program */ void foo () { int x; /* Lifetime of foo () */ } Here, global is statically allocated: It is allocated by the compiler It is created when the program starts It disappears when the program exits © 2021 Ethan Blanton / CSE 220: Systems Programming 4 Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary Examples int global ; /* Lifetime of program */ void foo () { int x; /* Lifetime of foo () */ } Whereas x is automatically allocated: It is allocated by the compiler It is created when foo() is called ¶ It disappears when foo() returns © 2021 Ethan Blanton / CSE 220: Systems Programming 5 Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary The Heap The heap represents memory that is: allocated and released at run time managed explicitly by the programmer only obtainable by address Heap memory is just a range of bytes to C. -

Bidirectional Typing

Bidirectional Typing JANA DUNFIELD, Queen’s University, Canada NEEL KRISHNASWAMI, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom Bidirectional typing combines two modes of typing: type checking, which checks that a program satisfies a known type, and type synthesis, which determines a type from the program. Using checking enables bidirectional typing to support features for which inference is undecidable; using synthesis enables bidirectional typing to avoid the large annotation burden of explicitly typed languages. In addition, bidirectional typing improves error locality. We highlight the design principles that underlie bidirectional type systems, survey the development of bidirectional typing from the prehistoric period before Pierce and Turner’s local type inference to the present day, and provide guidance for future investigations. ACM Reference Format: Jana Dunfield and Neel Krishnaswami. 2020. Bidirectional Typing. 1, 1 (November 2020), 37 pages. https: //doi.org/10.1145/nnnnnnn.nnnnnnn 1 INTRODUCTION Type systems serve many purposes. They allow programming languages to reject nonsensical programs. They allow programmers to express their intent, and to use a type checker to verify that their programs are consistent with that intent. Type systems can also be used to automatically insert implicit operations, and even to guide program synthesis. Automated deduction and logic programming give us a useful lens through which to view type systems: modes [Warren 1977]. When we implement a typing judgment, say Γ ` 4 : 퐴, is each of the meta-variables (Γ, 4, 퐴) an input, or an output? If the typing context Γ, the term 4 and the type 퐴 are inputs, we are implementing type checking. If the type 퐴 is an output, we are implementing type inference. -

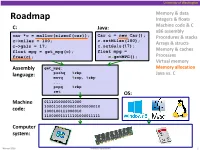

Memory Allocation Pushq %Rbp Java Vs

University of Washington Memory & data Roadmap Integers & floats C: Java: Machine code & C x86 assembly car *c = malloc(sizeof(car)); Car c = new Car(); Procedures & stacks c.setMiles(100); c->miles = 100; Arrays & structs c->gals = 17; c.setGals(17); float mpg = get_mpg(c); float mpg = Memory & caches free(c); c.getMPG(); Processes Virtual memory Assembly get_mpg: Memory allocation pushq %rbp Java vs. C language: movq %rsp, %rbp ... popq %rbp ret OS: Machine 0111010000011000 100011010000010000000010 code: 1000100111000010 110000011111101000011111 Computer system: Winter 2016 Memory Allocation 1 University of Washington Memory Allocation Topics Dynamic memory allocation . Size/number/lifetime of data structures may only be known at run time . Need to allocate space on the heap . Need to de-allocate (free) unused memory so it can be re-allocated Explicit Allocation Implementation . Implicit free lists . Explicit free lists – subject of next programming assignment . Segregated free lists Implicit Deallocation: Garbage collection Common memory-related bugs in C programs Winter 2016 Memory Allocation 2 University of Washington Dynamic Memory Allocation Programmers use dynamic memory allocators (such as malloc) to acquire virtual memory at run time . For data structures whose size (or lifetime) is known only at runtime Dynamic memory allocators manage an area of a process’ virtual memory known as the heap User stack Top of heap (brk ptr) Heap (via malloc) Uninitialized data (.bss) Initialized data (.data) Program text (.text) 0 Winter 2016 Memory Allocation 3 University of Washington Dynamic Memory Allocation Allocator organizes the heap as a collection of variable-sized blocks, which are either allocated or free . Allocator requests pages in heap region; virtual memory hardware and OS kernel allocate these pages to the process . -

Unleashing the Power of Allocator-Aware Software

P2126R0 2020-03-02 Pablo Halpern (on behalf of Bloomberg): [email protected] John Lakos: [email protected] Unleashing the Power of Allocator-Aware Software Infrastructure NOTE: This white paper (i.e., this is not a proposal) is intended to motivate continued investment in developing and maturing better memory allocators in the C++ Standard as well as to counter misinformation about allocators, their costs and benefits, and whether they should have a continuing role in the C++ library and language. Abstract Local (arena) memory allocators have been demonstrated to be effective at improving runtime performance both empirically in repeated controlled experiments and anecdotally in a variety of real-world applications. The initial development and subsequent maintenance effort of implementing bespoke data structures using custom memory allocation, however, are typically substantial and often untenable, especially in the limited timeframes that urgent business needs impose. To address such recurring performance needs effectively across the enterprise, Bloomberg has adopted a consistent, ubiquitous allocator-aware software infrastructure (AASI) based on the PMR-style1 plug-in memory allocator protocol pioneered at Bloomberg and adopted into the C++17 Standard Library. In this paper, we highlight the essential mechanics and subtle nuances of programing on top of Bloomberg’s AASI platform. In addition to delineating how to obtain performance gains safely at minimal development cost, we explore many of the inherent collateral benefits — such as object placement, metrics gathering, testing, debugging, and so on — that an AASI naturally affords. After reading this paper and surveying the available concrete allocators (provided in Appendix A), a competent C++ developer should be adequately equipped to extract substantial performance and other collateral benefits immediately using our AASI. -

P1083r2 | Move Resource Adaptor from Library TS to the C++ WP

P1083r2 | Move resource_adaptor from Library TS to the C++ WP Pablo Halpern [email protected] 2018-11-13 | Target audience: LWG 1 Abstract When the polymorphic allocator infrastructure was moved from the Library Fundamentals TS to the C++17 working draft, pmr::resource_adaptor was left behind. The decision not to move pmr::resource_adaptor was deliberately conservative, but the absence of resource_adaptor in the standard is a hole that must be plugged for a smooth transition to the ubiquitous use of polymorphic_allocator, as proposed in P0339 and P0987. This paper proposes that pmr::resource_adaptor be moved from the LFTS and added to the C++20 working draft. 2 History 2.1 Changes from R1 to R2 (in San Diego) • Paper was forwarded from LEWG to LWG on Tuesday, 2018-10-06 • Copied the formal wording from the LFTS directly into this paper • Minor wording changes as per initial LWG review • Rebased to the October 2018 draft of the C++ WP 2.2 Changes from R0 to R1 (pre-San Diego) • Added a note for LWG to consider clarifying the alignment requirements for resource_adaptor<A>::do_allocate(). • Changed rebind type from char to byte. • Rebased to July 2018 draft of the C++ WP. 3 Motivation It is expected that more and more classes, especially those that would not otherwise be templates, will use pmr::polymorphic_allocator<byte> to allocate memory. In order to pass an allocator to one of these classes, the allocator must either already be a polymorphic allocator, or must be adapted from a non-polymorphic allocator. The process of adaptation is facilitated by pmr::resource_adaptor, which is a simple class template, has been in the LFTS for a long time, and has been fully implemented. -

Programming with Gadts

Chapter 8 Programming with GADTs ML-style variants and records make it possible to define many different data types, including many of the types we encoded in System F휔 in Chapter 2.4.1: booleans, sums, lists, trees, and so on. However, types defined this way can lead to an error-prone programming style. For example, the OCaml standard library includes functions List .hd and List . tl for accessing the head and tail of a list: val hd : ’ a l i s t → ’ a val t l : ’ a l i s t → ’ a l i s t Since the types of hd and tl do not express the requirement that the argu- ment lists be non-empty, the functions can be called with invalid arguments, leading to run-time errors: # List.hd [];; Exception: Failure ”hd”. In this chapter we introduce generalized algebraic data types (GADTs), which support richer types for data and functions, avoiding many of the errors that arise with partial functions like hd. As we shall see, GADTs offer a num- ber of benefits over simple ML-style types, including the ability to describe the shape of data more precisely, more informative applications of the propositions- as-types correspondence, and opportunities for the compiler to generate more efficient code. 8.1 Generalising algebraic data types Towards the end of Chapter 2 we considered some different approaches to defin- ing binary branching tree types. Under the following definition a tree is either empty, or consists of an element of type ’a and a pair of trees: type ’ a t r e e = Empty : ’ a t r e e | Tree : ’a tree * ’a * ’a tree → ’ a t r e e 59 60 CHAPTER 8. -

The Slab Allocator: an Object-Caching Kernel Memory Allocator

The Slab Allocator: An Object-Caching Kernel Memory Allocator Jeff Bonwick Sun Microsystems Abstract generally superior in both space and time. Finally, Section 6 describes the allocator’s debugging This paper presents a comprehensive design over- features, which can detect a wide variety of prob- view of the SunOS 5.4 kernel memory allocator. lems throughout the system. This allocator is based on a set of object-caching primitives that reduce the cost of allocating complex objects by retaining their state between uses. These 2. Object Caching same primitives prove equally effective for manag- Object caching is a technique for dealing with ing stateless memory (e.g. data pages and temporary objects that are frequently allocated and freed. The buffers) because they are space-efficient and fast. idea is to preserve the invariant portion of an The allocator’s object caches respond dynamically object’s initial state — its constructed state — to global memory pressure, and employ an object- between uses, so it does not have to be destroyed coloring scheme that improves the system’s overall and recreated every time the object is used. For cache utilization and bus balance. The allocator example, an object containing a mutex only needs also has several statistical and debugging features to have mutex_init() applied once — the first that can detect a wide range of problems throughout time the object is allocated. The object can then be the system. freed and reallocated many times without incurring the expense of mutex_destroy() and 1. Introduction mutex_init() each time. An object’s embedded locks, condition variables, reference counts, lists of The allocation and freeing of objects are among the other objects, and read-only data all generally qual- most common operations in the kernel. -

Scala by Example (2009)

Scala By Example DRAFT January 13, 2009 Martin Odersky PROGRAMMING METHODS LABORATORY EPFL SWITZERLAND Contents 1 Introduction1 2 A First Example3 3 Programming with Actors and Messages7 4 Expressions and Simple Functions 11 4.1 Expressions And Simple Functions...................... 11 4.2 Parameters.................................... 12 4.3 Conditional Expressions............................ 15 4.4 Example: Square Roots by Newton’s Method................ 15 4.5 Nested Functions................................ 16 4.6 Tail Recursion.................................. 18 5 First-Class Functions 21 5.1 Anonymous Functions............................. 22 5.2 Currying..................................... 23 5.3 Example: Finding Fixed Points of Functions................ 25 5.4 Summary..................................... 28 5.5 Language Elements Seen So Far....................... 28 6 Classes and Objects 31 7 Case Classes and Pattern Matching 43 7.1 Case Classes and Case Objects........................ 46 7.2 Pattern Matching................................ 47 8 Generic Types and Methods 51 8.1 Type Parameter Bounds............................ 53 8.2 Variance Annotations.............................. 56 iv CONTENTS 8.3 Lower Bounds.................................. 58 8.4 Least Types.................................... 58 8.5 Tuples....................................... 60 8.6 Functions.................................... 61 9 Lists 63 9.1 Using Lists.................................... 63 9.2 Definition of class List I: First Order Methods.............. -

An Ontology-Based Semantic Foundation for Organizational Structure Modeling in the ARIS Method

An Ontology-Based Semantic Foundation for Organizational Structure Modeling in the ARIS Method Paulo Sérgio Santos Jr., João Paulo A. Almeida, Giancarlo Guizzardi Ontology & Conceptual Modeling Research Group (NEMO) Computer Science Department, Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES) Vitória, ES, Brazil [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract—This paper focuses on the issue of ontological Although present in most enterprise architecture interpretation for the ARIS organization modeling language frameworks, a semantic foundation for organizational with the following contributions: (i) providing real-world modeling elements is still lacking [1]. This is a significant semantics to the primitives of the language by using the UFO challenge from the perspective of modelers who must select foundational ontology as a semantic domain; (ii) the and manipulate modeling elements to describe an Enterprise identification of inappropriate elements of the language, using Architecture and from the perspective of stakeholders who a systematic ontology-based analysis approach; and (iii) will be exposed to models for validation and decision recommendations for improvements of the language to resolve making. In other words, a clear semantic account of the the issues identified. concepts underlying Enterprise Modeling languages is Keywords: semantics for enterprise models; organizational required for Enterprise Models to be used as a basis for the structure; ontological interpretation; ARIS; UFO (Unified management, design and evolution of an Enterprise Foundation Ontology) Architecture. In this paper we are particularly interested in the I. INTRODUCTION modeling of this architectural domain in the widely- The need to understand and manage the evolution of employed ARIS Method (ARchitecture for integrated complex organizations and its information systems has given Information Systems). -

Fast Efficient Fixed-Size Memory Pool: No Loops and No Overhead

COMPUTATION TOOLS 2012 : The Third International Conference on Computational Logics, Algebras, Programming, Tools, and Benchmarking Fast Efficient Fixed-Size Memory Pool No Loops and No Overhead Ben Kenwright School of Computer Science Newcastle University Newcastle, United Kingdom, [email protected] Abstract--In this paper, we examine a ready-to-use, robust, it can be used in conjunction with an existing system to and computationally fast fixed-size memory pool manager provide a hybrid solution with minimum difficulty. On with no-loops and no-memory overhead that is highly suited the other hand, multiple instances of numerous fixed-sized towards time-critical systems such as games. The algorithm pools can be used to produce a general overall flexible achieves this by exploiting the unused memory slots for general solution to work in place of the current system bookkeeping in combination with a trouble-free indexing memory manager. scheme. We explain how it works in amalgamation with Alternatively, in some time critical systems such as straightforward step-by-step examples. Furthermore, we games; system allocations are reduced to a bare minimum compare just how much faster the memory pool manager is to make the process run as fast as possible. However, for when compared with a system allocator (e.g., malloc) over a a dynamically changing system, it is necessary to allocate range of allocations and sizes. memory for changing resources, e.g., data assets Keywords-memory pools; real-time; memory allocation; (graphical images, sound files, scripts) which are loaded memory manager; memory de-allocation; dynamic memory dynamically at runtime. -

Effective STL

Effective STL Author: Scott Meyers E-version is made by: Strangecat@epubcn Thanks is given to j1foo@epubcn, who has helped to revise this e-book. Content Containers........................................................................................1 Item 1. Choose your containers with care........................................................... 1 Item 2. Beware the illusion of container-independent code................................ 4 Item 3. Make copying cheap and correct for objects in containers..................... 9 Item 4. Call empty instead of checking size() against zero. ............................. 11 Item 5. Prefer range member functions to their single-element counterparts... 12 Item 6. Be alert for C++'s most vexing parse................................................... 20 Item 7. When using containers of newed pointers, remember to delete the pointers before the container is destroyed. ........................................................... 22 Item 8. Never create containers of auto_ptrs. ................................................... 27 Item 9. Choose carefully among erasing options.............................................. 29 Item 10. Be aware of allocator conventions and restrictions. ......................... 34 Item 11. Understand the legitimate uses of custom allocators........................ 40 Item 12. Have realistic expectations about the thread safety of STL containers. 43 vector and string............................................................................48 Item 13. Prefer vector