First Day of Battle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Position Was Finely Adapted to Its Use...”

"...Our Position Was Finely Adapted To Its Use...” The Guns of Cemetery Hill Bert H. Barnett During the late afternoon of July 1, 1863, retiring Federals of the battered 1st and 11th corps withdrew south through Gettysburg toward Cemetery Hill and began to steady themselves upon it. Following the difficult experiences of the first day of battle, many officers and men were looking to that solid piece of ground, seeking all available advantages. A number of factors made this location attractive. Chief among them was a broad, fairly flat crest that rose approximately eighty feet above the center of Gettysburg, which lay roughly three-quarters of a mile to the north. Cemetery Hill commanded the approaches to the town from the south, and the town in turn served as a defensive bulwark against organized attack from that quarter. To the west and southwest of the hill, gradually descending open slopes were capable of being swept by artillery fire. The easterly side of the hill was slightly lower in height than the primary crest. Extending north of the Baltimore pike, it possessed a steeper slope that overlooked low ground, cleared fields, and a small stream. Field guns placed on this position would also permit an effective defense. It was clear that this new position possessed outstanding features. General Oliver Otis Howard, commanding the Union 11th Corps, pronounced it “the only tenable position” for the army.1 As the shadows began to lengthen on July 1, it became apparent that Federal occupation of the hill was not going to be challenged in any significant manner this day. -

The Gettysburg Address Was Written in 1863

Four score and seven years ago… A “score” is 20 years. Four score equals 80 years. Four score and seven years would be 87 years. The Gettysburg Address was written in 1863. 87 years before that was 1776, the year of the Declaration of Independence. Therefore Lincoln is asking his audience to look back at the ideals written in the Declaration of Independence. This image is courtesy of archives.gov. …our fathers… This painting shows the committee to draft the Declaration of Independence. The “Founding Fathers” who made up this committee are from left to right: Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston, John Adams, and Roger Sherman. The original black and white drawing, titled “Drafting the Declaration of Independence” was completed by Alonzo Chappel (1882-1887) circa 1896. The colorized version is courtesy of brittanica.com. …brought forth… This painting by John Trumbull (1756-1843) depicts the moment in 1776 when the first draft of the Declaration of Independence was presented to the Second Continental Congress. This painting was completed in 1818 and placed in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol in 1826. …on this continent… This is a map of the continent of North America. It is called a “political map” because the outline of countries, states, and provinces are outlined. This image is courtesy of datemplate.com. …a new nation… The “new nation” brought forth on this continent was the United States of America. This image is courtesy of datemplate.com and mrhousch.com. …conceived in liberty… To “conceive” means to form an idea of. The United States was formed with the idea of liberty. -

The Influence of Local Remembrance on National Narratives of Gettysburg During the 19Th Century

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Contested Narratives: The Influence of Local Remembrance on National Narratives of Gettysburg During The 19th Century Jarrad A. Fuoss Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Fuoss, Jarrad A., "Contested Narratives: The Influence of Local Remembrance on National Narratives of Gettysburg During The 19th Century" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7177. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7177 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contested Narratives: The Influence of Local Remembrance on National Narratives of Gettysburg During The 19th Century. Jarrad A. Fuoss Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Science at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in 19th Century American History Jason Phillips, Ph.D., Chair Melissa Bingman, Ph.D. Brian Luskey, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2018 Keywords: Gettysburg; Civil War; Remembrance; Memory; Narrative Creation; National Identity; Citizenship; Race; Gender; Masculinity; Veterans. -

John Fulton Reynolds

John Fulton Reynolds By COL. JOHN FULTON REYNOLDS SCOTT ( U. S. Army, retired ) Grand-nephew of General Reynolds I CAME here to give a talk on John Fulton Reynolds, and as I have sat here this evening I really feel superfluous. The stu- dents of this school have certainly outdone themselves in their essays on that subject, and I feel that what I may add is more or less duplication. For the sake of the record I will do my best to make a brief talk, and to try to fill in some of the gaps in Reynolds' life which have been left out because some of them have not yet been published. As you have heard, John Reynolds was the second son of the nine children of John Reynolds and Lydia Moore. Lydia Moore's ancestry was entirely Irish. Her father came from Rathmelton, Ireland, served as a captain at Brandywine with the 3rd Penn- sylvania. Infantry of the Continental Line, where he was wounded; also served at Germantown and at Valley Forge, and was then retired. Her mother was Irish on both sides of her family, and the Reynolds family itself was Irish, but, of course, the Huguenot strain came in through John Reynolds' own mother, who was a LeFever and a great-granddaughter of Madam Ferree of Paradise. Our subject was born on September 21, 1820, at 42 West King Street, Lancaster, and subsequently went to the celebrated school at Lititz, conducted by the grandfather of the presiding officer of this meeting, Dr. Herbert H. Beck. I have a letter written by John F. -

Lee's Mistake: Learning from the Decision to Order Pickett's Charge

Defense Number 54 A publication of the Center for Technology and National Security Policy A U G U S T 2 0 0 6 National Defense University Horizons Lee’s Mistake: Learning from the Decision to Order Pickett’s Charge by David C. Gompert and Richard L. Kugler I think that this is the strongest position on which Robert E. Lee is widely and rightly regarded as one of the fin- to fight a battle that I ever saw. est generals in history. Yet on July 3, 1863, the third day of the Battle — Winfield Scott Hancock, surveying his position of Gettysburg, he ordered a frontal assault across a mile of open field on Cemetery Ridge against the strong center of the Union line. The stunning Confederate It is my opinion that no 15,000 men ever arrayed defeat that ensued produced heavier casualties than Lee’s army could for battle can take that position. afford and abruptly ended its invasion of the North. That the Army of Northern Virginia could fight on for 2 more years after Gettysburg was — James Longstreet to Robert E. Lee, surveying a tribute to Lee’s abilities.1 While Lee’s disciples defended his decision Hancock’s position vigorously—they blamed James Longstreet, the corps commander in This is a desperate thing to attempt. charge of the attack, for desultory execution—historians and military — Richard Garnett to Lewis Armistead, analysts agree that it was a mistake. For whatever reason, Lee was reti- prior to Pickett’s Charge cent about his reasoning at the time and later.2 The fault is entirely my own. -

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015 Marker Text One-quarter mile south of this marker is the home of General Solomon A. Meredith, Iron Brigade Commander at Gettysburg. Born in North Carolina, Meredith was an Indiana political leader and post-war Surveyor-General of Montana Territory. Report The Bureau placed this marker under review because its file lacked both primary and secondary documentation. IHB researchers were able to locate primary sources to support the claims made by the marker. The following report expands upon the marker points and addresses various omissions, including specifics about Meredith’s political service before and after the war. Solomon Meredith was born in Guilford County, North Carolina on May 29, 1810.1 By 1830, his family had relocated to Center Township, Wayne County, Indiana.2 Meredith soon turned to farming and raising stock; in the 1850s, he purchased property near Cambridge City, which became known as Oakland Farm, where he grew crops and raised award-winning cattle.3 Meredith also embarked on a varied political career. He served as a member of the Wayne County Whig convention in 1839.4 During this period, Meredith became concerned with state internal improvements: in the early 1840s, he supported the development of the Whitewater Canal, which terminated in Cambridge City.5 Voters next chose Meredith as their representative to the Indiana House of Representatives in 1846 and they reelected him to that position in 1847 and 1848.6 From 1849-1853, Meredith served -

R-456 Page 1 of 1 2016 No. R-456. Joint Resolution Supporting The

R-456 Page 1 of 1 2016 No. R-456. Joint resolution supporting the posthumous awarding of the Congressional Medal of Honor to Civil War Brigadier General George Jerrison Stannard. (J.R.H.28) Offered by: Representatives Turner of Milton, Hubert of Milton, Johnson of South Hero, Krebs of South Hero, Devereux of Mount Holly, Branagan of Georgia, Jerman of Essex, and Troiano of Stannard Whereas, Civil War Brigadier General George Jerrison Stannard, a native of Georgia, Vermont, commanded the Second Vermont Brigade, and Whereas, the Second Vermont Brigade (Stannard’s Brigade), untested in battle, reached Gettysburg on July 1, 1863 at the end of the first day’s fighting, and Whereas, Stannard’s Brigade fought ably late on the battle’s second day, helping to stabilize the threatened Union line, and earning it a place at the front of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, and Whereas, on the battle’s final day, in perhaps the most memorable Confederate maneuver of the Civil War that became known as Pickett’s Charge, the Confederate troops approached the Union line, but they suddenly shifted their direction northward, leaving no enemy troops in front of the Vermonters, and Whereas, General Stannard recognized this unexpected opportunity and ordered the Brigade’s 13th and 16th regiments to “change front forward on first company,” sending 900 Vermonters in a great wheeling motion to the front of the Union lines, and Whereas, Stannard’s men hit the exposed right flank of Pickett’s Charge in an attack the Confederates did not expect, inflicting hundreds of casualties, and Whereas, Major Abner Doubleday, commanding the Army of the Potomac’s I Corps, in which the Vermonters served, commented that General Stannard’s strategy helped to ensure, if not guarantee, the Union’s victory at Gettysburg, and Whereas, Confederate General Robert E. -

Battle of Gettysburg Day 1 Reading Comprehension Name: ______

Battle of Gettysburg Day 1 Reading Comprehension Name: _________________________ Read the passage and answer the questions. The Ridges of Gettysburg Anticipating a Confederate assault, Union Brigadier General John Buford and his soldiers would produce the first line of defense. Buford positioned his defenses along three ridges west of the town. Buford's goal was simply to delay the Confederate advance with his small cavalry unit until greater Union forces could assemble their defenses on the three storied ridges south of town known as Cemetery Ridge, Cemetery Hill, and Culp's Hill's. These ridges were crucial to control of Gettysburg. Whichever army could successfully occupy these heights would have superior position and would be difficult to dislodge. The Death of Major General Reynolds The first of the Confederate forces to engage at Gettysburg, under the Command of Major General Henry Heth, succeeded in advancing forward despite Buford's defenses. Soon, battles erupted in several locations, and Union forces would suffer severe casualties. Union Major General John Reynolds would be killed in battle while positioning his troops. Major General Abner Doubleday, the man eventually credited with inventing the formal game of baseball, would assume command. Fighting would intensify on a road known as the Chambersburg Pike, as Confederate forces continued to advance. Jubal Early's Successful Assault Meanwhile, Union defenses positioned north and northwest of town would soon be outflanked by Confederates under the command of Jubal Early and Robert Rodes. Despite suffering severe casualties, Early's soldiers would break through the line under the command of Union General Francis Barlow, attacking them from multiple sides and completely overwhelming them. -

(NPS) Law Enforcement Incident Reports at Gettysburg National Military Park, 04-July-2020 Through 29-July-2020

Description of document: Each National Park Service (NPS) law enforcement incident reports at Gettysburg National Military Park, 04-July-2020 through 29-July-2020 Requested date: 20-July-2020 Release date: 11-August-2020 Posted date: 17-August-2020 Source of document: FOIA Request National Park Service 1100 Ohio Drive, SW Washington, DC 20242 Fax: Call 202-619-7485 (voice) for options The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site, and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Interior Region 1- National Capital Area llOO Ohio Drive, S.W. -

Lincoln's Role in the Gettysburg Campaign

LINCOLN'S ROLE IN THE GETTYSBURG CAMPAIGN By EDWIN B. CODDINGTON* MOST of you need not be reminded that the battle of Gettys- burg was fought on the first three days of July, 1863, just when Grant's siege of Vicksburg was coming to a successful con- clusion. On July 4. even as Lee's and Meade's men lay panting from their exertions on the slopes of Seminary and Cemetery Ridges, the defenders of the mighty fortress on the Mississippi were laying down their arms. Independence Day, 1863, was, for the Union, truly a Glorious Fourth. But the occurrence of these two great victories at almost the same time raised a question then which has persisted up to the present: If the triumph at Vicksburg was decisive, why was not the one at Gettysburg equally so? Lincoln maintained that it should have been, and this paper is concerned with the soundness of his supposition. The Gettysburg Campaign was the direct outcome of the battle of Chancellorsville, which took place the first week in May. There General Robert E. Lee won a victory which, according to the bookmaker's odds, should have belonged to Major General "Fight- ing Joe" Hooker, if only because Hooker's army outnumbered the Confederates two to one and was better equipped. The story of the Chancel'orsville Campaign is too long and complicated to be told here. It is enough to say that Hooker's initial moves sur- prised his opponent, General Lee, but when Lee refused to react to his strategy in the way he anticipated, Hooker lost his nerve and from then on did everything wrong. -

Rediscovered

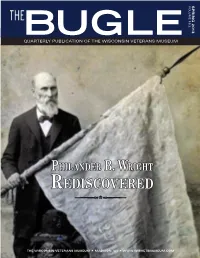

VOLUME 19:2 2013 SPRING QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM PHILANDER B. WRIGHT REDISCOVERED THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM MADISON, WI WWW.WISVETSMUSEUM.COM FROM THE SECRETARY sure there was strong support Exhibit space was quickly for the museum all around the filled, as relics from those state, from veterans and non- subsequent wars vastly veterans alike. enlarged our collections and How the Wisconsin Veterans the museum became more Museum came to be on the and more popular. By the Capitol Square in its current 1980s, it was clear that our incarnation is best answered museum needed more space by the late Dr. Richard Zeitlin. for exhibits and visitors. Thus, As the former curator of the with the support of many G.A.R. Memorial Hall Museum Veterans Affairs secretaries, in the State Capitol and the Governor Thompson and Wisconsin War Museum at the many legislators, we were Wisconsin Veterans Home, he able to acquire the space and was a firsthand witness to the develop the exhibits that now history of our museum. make the Wisconsin Veterans Zeitlin pointed to a 1901 Museum a premiere historical law that mandated that state attraction in the State of officials establish a memorial Wisconsin. WDVA SECRETARY JOHN SCOCOS dedicated to commemorating The Wisconsin Department Wisconsin’s role in the Civil of Veterans Affairs is proud FROM THE SECRETARY War and any subsequent of our museum and as we Greetings! The Wisconsin war as a starting point for commemorate our 20th Veterans Museum as you the museum. After the State anniversary in its current know it today opened on Capitol was rebuilt following location, we are also working June 6, 1993. -

PICKETT's CHARGE Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT

PICKETT’S CHARGE I Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT PROGRAM U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Pickett's Charge A Student Education Program at Gettysburg National Military Park TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 How To Use This Booklet ••••..••.••...• 3 Section 2 Program Overview . • . • . • . • . 4 Section 3 Field Trip Day Procedures • • • . • • • . 5 Section 4 Essential Background and Activities . 6 A Causes ofthe American Civil War ••..•...... 7 ft The Battle ofGettysburg . • • • . • . 10 A Pi.ckett's Charge Vocabulary •............... 14 A Name Tags ••.. ... ...........• . •......... 15 A Election ofOfficers and Insignia ......•..•.. 15 A Assignm~t ofSoldier Identity •..••......... 17 A Flag-Making ............................. 22 ft Drill of the Company (Your Class) ........... 23 Section 5 Additional Background and Activities .••.. 24 Structure ofthe Confederate Army .......... 25 Confederate Leaders at Gettysburg ••.•••.••• 27 History of the 28th Virginia Regiment ....... 30 History of the 57th Virginia Regiment . .. .... 32 Infantry Soldier Equipment ................ 34 Civil War Weaponry . · · · · · · 35 Pre-Vtsit Discussion Questions . • . 37 11:me Line . 38 ... Section 6 B us A ct1vities ........................• 39 Soldier Pastimes . 39 Pickett's Charge Matching . ••.......•....... 43 Pickett's Charge Matching - Answer Key . 44 •• A .•. Section 7 P ost-V 1s1t ctivities .................... 45 Post-Visit Activity Ideas . • . • . • . • . 45 After Pickett's Charge . • • • • . • . 46 Key: ft = Essential Preparation for Trip 2 Section 1 How to Use This Booklet Your students will gain the most benefit from this program if they are prepared for their visit. The preparatory information and activities in this booklet are necessary because .. • students retain the most information when they are pre pared for the field trip, knowing what to expect, what is expected of them, and with some base of knowledge upon which the program ranger can build.