Clarifying the Complexity and Ambivalence of the Cultural Industries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eco-Trend As a New Tendency in the Fashion Industry and Its Influence on Modern Design

THE ECO-TREND AS A NEW TENDENCY IN THE FASHION INDUSTRY AND ITS INFLUENCE ON MODERN DESIGN AUTHORSHIP INTRODUCTION Svitlana Oborska Global environmental problems have become Docent, Associate Professor of the Department of Event one of the reasons for the formation of a new Management and Leisure Industry Kyiv National University of the Culture and Arts, Associate Professor of the Department of Event concept in design. In the fashion industry, the Management and Leisure Industry, Kyiv National University of the Culture and Arts. term "environmental sustainability" or "conscious fashion" - the safe use of the ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3148-6325 E-mail: [email protected] planet's natural resources and ensuring Liudmyla Bilozub environmental and social safety - is becoming increasingly common. Professor assistant, PhD in History of Arts, Zaporizhzhia National University. It is known that clothes should not only ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2384-827X aesthetic, but also have a direct physiological E-mail: [email protected] impact on people, so clothing design has Oksana Minenko rapidly responded to the need for a conscious Associate Professor at the Department of Design of the Faculty of approach to environmental issues. The search Art and Design, Candidate of Art and Criticism, Department of Design of the Faculty of Art and Design, Municipal Institution of for new materials, new methods of natural Higher Education "Khortytsia National Educational Rehabilitation dyeing of fabrics, the use of recycled fibers in Academy" of Zaporizhzhia Regional Council. weaving, the restoration of traditional crafts ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4210-5778 that are used in clothing production - all this E-mail: [email protected] has grown from an unpopular theory to a Oleksandra Penchuk stable and generally applied practical activity Candidate of Technical Sciences, Associate Professor, under the general definition of eco-design. -

Introduction

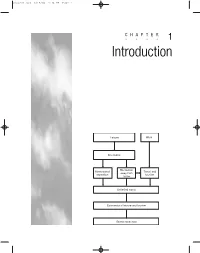

Chap-01.qxd 8/17/04 3:34 PM Page 1 CHAPTER •••• 1 Introduction Leisure Work Recreation Recreation Home-based Travel and away from recreation tourism home Unlimited wants Economics of leisure and tourism Scarce resources Chap-01.qxd 8/17/04 3:34 PM Page 2 The Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism Objectives and learning outcomes • How important are recreation, leisure and tourism to national economies? • Why do these industries provide so many new jobs? • What is the globalization of recreation and leisure? • Are recreation, leisure and tourism shares good investments? • Is the growth of recreation, leisure and tourism sustainable? This book will help you investigate these issues. The objectives of this chapter are to define and integrate the areas of study of this book. First the scope of recreation, leisure and tourism will be discussed, and second the scope and techniques of economics will be outlined. The final part of the chapter explains how the study area of recreation, leisure and tourism can be analysed using economic techniques. By studying this chapter students will be able to: • understand the scope of recreation, leisure and tourism and their interrelationship; • explain the basic economic concerns of scarcity, choice and opportunity costs; • outline the allocation of resources in different economic systems; • explain the methodology of economics; • understand the use of models in economics; • understand the use of economics to analyse issues in recreation, leisure and tourism; • access sources of information. Definition and scope of recreation, leisure and tourism Like all definitions, those pertaining to recreation, leisure and tourism encounter some problems. -

A Study on the Fashion Styles of the Wellness Kin in the Contemporary Fashion

Journal of Fashion Business Vol. 6, No. 6, pp.19~33(2002) A Study on the Fashion Styles of the Wellness Kin in the Contemporary Fashion Kan, Ho-Sup* and Park, Na-Na Assoc. Prof., Dept. of Fashion Design, Dongduk Women’s University* M.A., Dept. of Fashion Design, Dongduk Women’s University Abstract In the middle of economic and mental riches in the 21st century, the importance of well being and the pursuit of happiness are emerging as the new trend. Thus the lifestyle that values comfortable and practical naturalness and intrinsic merits has come to influence the human life rather than the old showing-off and formal desire. In addition to this, the spread of the five day week has given more leisure time, which has led to the increasing interest in health and leisure. The interest in sports has skyrocketed since the successful holding of the 2002 Korea and Japan World Cup event. All these changes to the lifestyle have contributed to the fusion of luxury wear and sports wear. As the result of the consumers in the 21st century having more classified and upgraded way of living thanks to the settlement of the above-mentioned lifestyle and the enlargement of the leisure sports culture, there has appeared the wellness kin, who value the importance of life and the nature and believe in the idea that they can reconstruct the environment in the way they can enjoy their lifestyle and pursue happiness. They favor healthy fashion items and think much of exercise, nutrition, and rest. They pursue the natural and comfortable style, whose ideas came from simple exercises such as health training and yoga and the easy and comfortable look observed at resorts. -

GCSE Leisure and Tourism 2009 Unit1.Pdf

GCSE Leisure & Tourism – Investigating Leisure & Tourism in a chosen area 2.1.2 A Introduction to Leisure and Tourism Leisure Every person has things that they have to do. Many adults have to go to work; someone has to do the shopping, prepare meals, and clean the house and so on. Students and children have to go to school or college and may have homework projects to do after school has finished. Also, every person has to sleep, wash and shower usually for somewhere between 6 to 8 hours each night. When all these things have been completed there is time left over, and this time is a person’s leisure time. During this time, people choose to do what they enjoy doing rather than what they have to do. Put another way: Leisure time is the opportunity available to a person after completing the immediate necessities of life. During this time the person has the freedom to choose what activities to take part in. Another term used is a person’s free time. Some people choose to do very little in their leisure time and may watch television, listen to music or read a newspaper. All of these are very popular leisure activities. They are all things which many people choose to do because they can be done at home and cost very little money. Also, they are activities which people can enjoy on their own. Each person can decide what to do in their leisure time and there are many factors which influence this choice, including the age of the person, their family and friends, their religion and culture, the money they have to spend on leisure and where they live. -

Constructive Suggestions on the Development of Leisure Sports

6th International Conference on Electronic, Mechanical, Information and Management (EMIM 2016) Constructive Suggestions on the Development of Leisure Sports Industry in Ganzhou Renzhuo Zhang School of Science, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, Ganzhou, China [email protected] Keywords: Ganzhou; Leisure sports; Industry; Suggestion Abstract. This article studies the current situation of leisure sports industry in Ganzhou by using literature consultation, interview method and field research method. And through relevant researches on the current situation, problems existing in the development of leisure sports industry had been found, and thus corresponding suggestions were proposed: create good leisure sports environment to attract tourists from various places and promote further development of this industry; then enhance propaganda, and establish scientific leisure sports values, the development of leisure sports should be connected with the nationwide fitness campaign tightly; the school should establish new educational philosophy; pay more attention on cultivating social sports instructors, popularize red sports to boost the development of leisure sports industry. Introduction Leisure time is an inevitable rules for social development, “the coming of the leisure time” would provide opportunity for the development of leisure sports development, and as a cultural, scientific and healthy ways of life, it could help people gain spiritual motivations for life at the same time of promoting healthy development of both the body and the mind, it plays an important role in increasing the overall quality of people; also, has significant effect on promoting the development of industrial economy and the society and interpersonal communication, the vitality of the sports cause and the perfection of the life-long education system. -

Local Communities' Incentives for Forest Conservation

LOCAL COMMUNITIES’ INCENTIVES FOR FOREST CONSERVATION: CASE OF KAKAMEGA FOREST IN KENYA By Paul Guthiga1* and John Mburu1 A Paper Presented at the 11th Biannual Conference of International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP) Bali, Indonesia June 19th to June 23rd 2006 Survival of the Commons: Mounting Challenges and New Realities 1Center for Development Research (ZEF), University of Bonn, Walter-Flex-Str. 3, D53113 Bonn, Germany * Corresponding author: Tel +49-228-731731, Fax +49-228-731869, E-mail: [email protected] The authors would like to express their grateful appreciation to the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) for providing funding for this study through the Biodiversity Analysis Transect for Africa (BIOTA)-East project. ABSTRACT The study is based on a biodiversity-rich remnant of a tropical rainforest located in western Kenya under immense threat of survival. The forest is located in a densely populated area inhabited by poor farming communities. Currently the forest is managed by three management regimes each carrying out its function in a different manner. The study identifies, describes and where possible quantifies the various conservation incentives (both economic and non-economic) offered by the three management regimes. Further, the study analyses local people’s perception of management regimes by generating management satisfaction rankings; both overall and for specific management aspects. The findings of the study indicate that extraction of direct forest products is the main incentive offered by two of the regimes. The local people obtain substantial financial benefits in the form of products they extract from the forest. Satisfaction ranking showed that the strictest regime among the three was ranked highest overall for it performance. -

Study on the New Pathway of Ecological Poverty Alleviation an Forest Health Industry Integrated Development

American Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering 2020; 4(4): 70-74 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajese doi: 10.11648/j.ajese.20200404.14 ISSN: 2578-7985 (Print); ISSN: 2578-7993 (Online) Study on the New Pathway of Ecological Poverty Alleviation an Forest Health Industry Integrated Development Weitao Xu 1, Heding Shen 1, Liqiang Zhang 1, Laicheng Yang 2, *, An Mao 2, *, Yifu Yuan 2, * 1Planning and Design Institute of Forest Products Industry of National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Beijing, China 2College of Forestry, Shandong Agricultural University, Taian, China Email address: *Corresponding author To cite this article: Weitao Xu, Heding Shen, Liqiang Zhang, Laicheng Yang, An Mao, Yifu Yuan. Study on the New Pathway of Ecological Poverty Alleviation an Forest Health Industry Integrated Development. American Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering . Vol. 4, No. 4, 2020, pp. 70-74. doi: 10.11648/j.ajese.20200404.14 Received : December 4, 2020; Accepted : December 14, 2020; Published : December 22, 2020 Abstract: Forest has the function of nourishing body and mind, promoting health, enhancing human immunity, which is of great significance to improve health index. Forest health care can give full play to the advantages of forest landscape, environment, space and culture, and extend forest functions. It is a new industry integrating forestry, health services, tourism and leisure industry, and is a new trend of sustainable development of forestry. Ecological poverty alleviation is a kind of poverty alleviation -

The Leisure Consumer 2021 Emerging from the Pandemic June 2021 the Leisure Consumer 2021 | Emerging from the Pandemic

The Leisure Consumer 2021 Emerging from the pandemic June 2021 The Leisure Consumer 2021 | Emerging from the pandemic Content Foreword ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 04 Infographic ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 05 A recovery in consumer confidence 06 Will COVID-19 have a lasting impact on the behaviours of leisure consumers? 09 Beyond COVID-19: Four leisure consumer profiles ����������������������������������������������������������� 13 Conclusion �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Authors and Contacts ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 20 2 The Leisure Consumer 2021 | Emerging from the pandemic The consumer data featured in this About this report: report is based on a survey carried out by independent market research agency, YouGov, on Deloitte’s behalf. This survey was conducted online with a nationally representative sample of more than 3,000 UK adults aged 18+ between 19 and 23 March. Some of the figures in this report show the results in the form of a net balance. This is calculated by subtracting the proportion of respondents that reported doing less of something from the proportion that reported doing -

Government of India Ministry of Tourism and Culture Department of Tourism Market Research Division

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF TOURISM AND CULTURE DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM MARKET RESEARCH DIVISION Final Report On 20 YEAR PERSPECTIVE PLAN FOR SUSTAINABLE TOURISM DEVLOPMENT IN UNION TERRITORY OF CHANDIGARH March 2003 Submitted by India Tourism Development Corporation TLC Marketing Pvt. Ltd. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India Private Limited 20 year Perspective Tourism Master Plan for Chandigarh Contents for the 20 Year perspective Tourism Master Plan 1. Executive Summary 1 2. The approach a. Guidelines for developing 20 year perspective Master Plans as issued by the Department of Tourism, Government of India 6 b. Background of Consortium partners 11 i. ITDC ii. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu iii. TLC Marketing Pvt Ltd c. Approach 15 d. Approach to Environmental Impact Assessment 19 3. Background on the State 21 a. History b. Physical features, Flora and Fauna c. Current infrastructure i. Access – Road, Rail, Air ii. Water & Sewage iii. Power – Electricity iv. Industrial Estates – list of major corporates d. Demographics versus other Northern States District Profiles e. Chandigarh Headquartered Corporate Houses 4. Current Tourism scenario in the State 38 a. Current Chandigarh Tourism Policy b. Inventory of Accommodation c. Current Tourism Statistics 1 20 year Perspective Tourism Master Plan for Chandigarh i. By city ii. Comparative with other Indian States – employment, project spends d. Taxes on Tourism activities e. Fairs & Festivals f. Roles of relevant bodies i. State Tourism Development ii. Urban Development & Town Planning iii. Industrial Development g. Tourism activities of contiguous States 5. Assessment of Tourism Attractions of the State 65 a. How other “City States” have developed tourism b. Inventory of attractions i. -

JUNE 3–5, 2018New York Marriott Marquis •

40TH ANNUAL NYU INTERNATIONAL HOSPITALITY INDUSTRY INVESTMENT CONFERENCE JUNE 3–5, 2018 New York Marriott Marquis • NYC Conference Chair Conference Host Jonathan M. Tisch Dennis Di Lorenzo Chairman and CEO of Loews Harvey J. Stedman Dean Hotels & Co. and Co-Chairman of NYU School of Professional Studies the Board of Loews Corporation Conference Vice Chair Conference Co-Host Jeffrey Stewart Nicolas Graf Founder, Walnut Hill Advisors Associate Dean NYU School of Professional Studies Jonathan M. Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism PARTICIPANT LIST CONFERENCE ATTENDEES Received and processed as of May 21, 2018 JONATHAN M. TISCH CENTER FOR HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM @nyuhospitality #nyuhospitality sps.nyu.edu/hospitalityconference Last Name First Name MI Title Company Work Addr 1 Work Addr 2 Work City Work State Work Zip Work Country E-mail Address Aboudou Jenny L. Canopy by Hilton Brand Management & Development Hilton 7930 Jones Branch Drive McLean VA 22102 USA [email protected] Acosta Dax Vice President, Acquisitions & Development Montage International 3 Ada Parkway Suite 100 Irvine CA 92618 USA [email protected] Acosta Luis C. Vice President Development Wischermann Partners, Inc. 40 Truffula Trail Orono MN 55356 USA [email protected] Adams Rick D. Chief Operating Officer Chesapeake Lodging Trust 4300 Wilson Boulevard Suite 625 Arlington VA 22203-4167 USA [email protected] Adamson Kirk P. Senior Vice President KSL Capital Partners 100 St Paul Suite 800 Denver CO 80206 USA [email protected] Adler Arthur Chairman, Americas, Hotels and Hospitality Group JLL Hotels & Hospitality 330 Madison Avenue 4th Floor New York NY 10017 USA [email protected] Advani Gurmit Principal General Hospitality Services 216 Centerview Drive Suite 155 Brentwood TN 37027 USA [email protected] Advani Nikheel Chief Operating Officer and Principal Grace Bay Resorts Unit 57 Saltmills Plaza Grace Bay Road Providenciales TKCA 1ZZ Turks and Caicos [email protected] Advani Prahlad S. -

Chapter 13 Future Perspectives of Recreation and Leisure

81590_CH13_FINAL.qxd:McLean 1/4/11 10:05 AM Page 389 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER 13 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR FUTURESALE OR DISTRIBUTION PERSPECTIVESNOT FOR SALE OF OR DISTRIBUTION RECREATION AND LEISURE © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION ᭜᭜᭜ Definition of Future: The future has always had a very special place in philoso- phy and, in general, in the human mind. This is true largely because human ©beings Jones often & want Bartlett a forecast Learning, of events that LLC will occur. It is perhaps possible© Jones to & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOTargue FORthat the SALE evolution OR of theDISTRIBUTION human brain is in great part an evolutionNOT in cog- FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION nitive abilities necessary to forecast the future, i.e., abstract imagination, logic, and induction. Imagination permits us to “see” (i.e., predict) a plausible model of a given situation without observing it, therefore mitigating risks. Logical rea- soning allows one to predict inevitable consequences of actions and situations © Jones & Bartlettand therefore Learning, gives useful LLC information about future ©events. Jones Induction & Bartlett permits Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEthe ORassociation DISTRIBUTION of a cause with consequences, a fundamentalNOT FOR notion SALE for every OR DISTRIBUTION forecast of future time.1 ᭜᭜᭜ © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION INTRODUCTIONNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION The remarkable growth of organized recreation, parks, and leisure services is docu- mented throughout this text. -

The Definition of Cultural Industries

The Definition of ‘Cultural Industries’ Dr. Justin O’Connor Director Manchester Institute for Popular Culture (www.mmu.ac.uk/h-ss/mipc) Manchester Metropolitan University Introduction The definition of the cultural industries has been the subject of intense debate over the last few years, especially within the framework of local, national and European policy development. This debate has been particularly frustrating. Though there is great and growing interest in this subject there are currently few real theoretical or policy models available. European conferences on this issue are the most frustrating, where arguments are primarily rhetorical and definitions made incommensurable by the most unimaginative empiricism. This situation of course reflects deeper conflicts and uncertainties with the concept, indicated by the complete absence of any policy paper from the EC on the subject. A policy framework for the cultural industries does present real organisational and administrative problems, but many of these stem from conceptual and definitional problems, reflecting profound transformations in the role of ‘culture’ in contemporary economy and society. The necessary uncertainty around these transformations have made make the full implications of the cultural industries debate unclear; but these implications have been treated more in terms of rhetoric than conceptual analysis because policy debates are also positional struggles. This can been seen in the way in which the debate very quickly turns to the ‘value’ of culture – constantly shifting between economic, social and aesthetic understandings of ‘value’. Couching discussion around the ‘value’ or ‘benefits’ of culture has been a major theme in the world of publicly funded arts and culture since the growing threat of budgetary cuts in the 1980s (though it has always been there).