'Visible Minority' Mpps in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto to Have the Canadian Jewish News Area Canada Post Publication Agreement #40010684 Havdalah: 7:53 Delivered to Your Door Every Week

SALE FOR WINTER $1229 including 5 FREE hotel nights or $998* Air only. *subject to availabilit/change Call your travel agent or EL AL. 416-967-4222 60 Pages Wednesday, September 26, 2007 14 Tishrei, 5768 $1.00 This Week Arbour slammed by two groups National Education continues Accused of ‘failing to take a balanced approach’ in Mideast conflict to be hot topic in campaign. Page 3 ognizing legitimate humanitarian licly against the [UN] Human out publicly about Iran’s calls for By PAUL LUNGEN needs of the Palestinians, we regret Rights Council’s one-sided obses- genocide.” The opportunity was Rabbi Schild honoured for Staff Reporter Arbour’s repeated re- sion with slamming there, he continued, because photos 60 years of service Page 16 sort to a one-sided Israel. As a former published after the event showed Louise Arbour, the UN high com- narrative that denies judge, we urge her Arbour, wearing a hijab, sitting Bar mitzvah boy helps missioner for Human Rights, was Israelis their essential to adopt a balanced close to the Iranian president. Righteous Gentile. Page 41 slammed by two watchdog groups right to self-defence.” approach.” Ahmadinejad was in New York last week for failing to take a bal- Neuer also criti- Neuer was refer- this week to attend a UN confer- Heebonics anced approach to the Arab-Israeli cized Arbour, a former ring to Arbour’s par- ence. His visit prompted contro- conflict and for ignoring Iran’s long- Canadian Supreme ticipation in a hu- versy on a number of fronts. Co- standing call to genocide when she Court judge, for miss- man rights meeting lumbia University, for one, came in attended a human rights conference ing an opportunity to of the Non-Aligned for a fair share of criticism for invit- in Tehran earlier this month. -

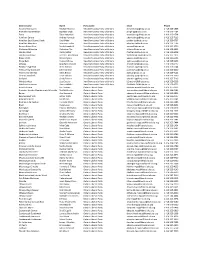

District Name

District name Name Party name Email Phone Algoma-Manitoulin Michael Mantha New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1938 Bramalea-Gore-Malton Jagmeet Singh New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1784 Essex Taras Natyshak New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0714 Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-7116 Hamilton East-Stoney Creek Paul Miller New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0707 Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1796 Kenora-Rainy River Sarah Campbell New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2750 Kitchener-Waterloo Catherine Fife New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6913 London West Peggy Sattler New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6908 London-Fanshawe Teresa J. Armstrong New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1872 Niagara Falls Wayne Gates New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 212-6102 Nickel Belt France GŽlinas New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-9203 Oshawa Jennifer K. French New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0117 Parkdale-High Park Cheri DiNovo New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0244 Timiskaming-Cochrane John Vanthof New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2000 Timmins-James Bay Gilles Bisson -

Renew Your 2013 Membership Or Join Paac Today!

www.publicaffairs.ca RENEW YOUR 2013 MEMBERSHIP OR JOIN PAAC TODAY! March 2013 By becoming a member of PAAC, you will gain the skills and connections you need to excel in your field. We offer meaningful membership benefits that can benefit you at all stages of your career, no matter your sector, job level or location. Membership benefits include access to the online PAAC membership directory, sizable event discounts and the cachet of belonging to Canada's premier public affairs association. View 2013 Membership Information Upcoming Events The Big Shift - The Seismic Change in PAAC Annual Conference - The Art & Whether it’s a conference, Canadian Politics, Business, and Science of Public Affairs: Tactics for seminar or social function, PAAC Culture and What it Means for Today and Tomorrow events have something for Our Future everyone. March 25, 2013 - Toronto, ON June 4, 2013 - Toronto, ON 8:00am – 9:30am View Details Details Coming Soon! New Ontario Liberal Leadership – and a Changed Political Landscape? Toronto, ON – On February 14, the PAAC welcomed representatives from the campaigns of candidates who sought to replace Dalton McGuinty as leader of the Ontario Liberal Party and Premier of Ontario. In front of a crowd of over 70 people and moderated by PAAC President John Capobianco, participants candidly discussed the challenges faced and strategies incorporated during the recently completed leadership campaign. Participants also provided those in attendance with an insider’s perspective from the Ontario Liberal Leadership Convention, offering seldom heard critical analysis of what resulted in an exciting and unpredictable finish. March 2013 ● Public Affairs Association of Canada (PAAC) ● www.publicaffairs.ca Page | 1 The PAAC would like to thank the following participants: Tom Allison – Campaign Manager – Kathleen Wynne Leadership Bid Bruce Davis – Campaign Manager – Eric Hoskins Leadership Bid Suzanne M. -

Harris Disorder’ and How Women Tried to Cure It

Advocating for Advocacy: The ‘Harris Disorder’ and how women tried to cure it The following article was originally commissioned by Action Ontarienne contre la violence faite aux femmes as a context piece in training material for transitional support workers. While it outlines the roots of the provincial transitional housing and support program for women who experience violence, the context largely details the struggle to sustain women’s anti-violence advocacy in Ontario under the Harris regime and the impacts of that government’s policy on advocacy work to end violence against women. By Eileen Morrow Political and Economic Context The roots of the Transitional Housing and Support Program began over 15 years ago. At that time, political and economic shifts played an important role in determining how governments approached social programs, including supports for women experiencing violence. Shifts at both the federal and provincial levels affected women’s services and women’s lives. In 1994, the federal government began to consider social policy shifts reflecting neoliberal economic thinking that had been embraced by capitalist powers around the world. Neoliberal economic theory supports smaller government (including cuts to public services), balanced budgets and government debt reduction, tax cuts, less government regulation, privatization of public services, individual responsibility and unfettered business markets. Forces created by neoliberal economics—including the current worldwide economic crisis—still determine how government operates in Canada. A world economic shift may not at first seem connected to a small program for women in Ontario, but it affected the way the Transitional Housing and Support Program began. Federal government shifts By 1995, the Liberal government in Ottawa was ready to act on the neoliberal shift with policy decisions. -

Back in the Tower Again

MUNICIPAL UPDATE Back In The Tower Again Angela Drennan THE SWEARING IN Toronto City Council was sworn in on December 4, 2018 to a Council Chamber full of family, friends and staff. The new Council is comprised of 25 Members including the Mayor, making it 26 (remember this now means to have an item passed at Council a majority +1 is needed, i.e. 14 votes). Councillor stalwart Frances Nunziata (Ward 5 York South Weston) was re-elected as the Speaker, a position she has held since 2010 and Councillor Shelley Carroll (Ward 17 Don Valley North) was elected as Deputy Speaker. The ceremonial meeting moved through the motions of pomp and circumstance with measured fanfare and Councillors, old and new, looking eager to get down to “real” work the next day during the official first meeting of City Council. Mayor Tory, during his first official address, stressed the need for Council consensus, not dissimilar to the previous term and reiterated his campaign positions on the dedication to build more affordable housing, address gun violence through youth programming and build transit, specifically the downtown relief line. Tory did suggest that the City still needs to take a financially prudent approach to future initiatives, as financial streams such as the land transfer tax have lessened due to a slower real estate market environment, a signal that cuts, reallocations or revenue tools will likely need to be revisited for debate during the term (the uploading of the TTC will help with the City’s financial burden, but isn’t enough). THE MAYOR’S OFFICE There have been some notable staff changes in Mayor John Tory’s Office, here are a few: We say goodbye to Vic Gupta, Tory’s Principal Secretary, who will be greatly missed but we say hello to Vince Gasparro, Liberal, Tory’s Campaign Co-Chair and longtime friend of the firm, who has taken over that position. -

Recent Immigration and the Formation of Visible Minority Neighbourhoods in Canada’S Large Cities

Catalogue no. 11F0019MIE — No. 221 ISSN: 1205-9153 ISBN: 0-662-37031-7 Research Paper Research Paper Analytical Studies Branch research paper series Recent immigration and the formation of visible minority neighbourhoods in Canada’s large cities By Feng Hou Business and Labour Market Analysis Division 24-F, R.H. Coats Building, Ottawa, K1A 0T6 Telephone: 1 800 263-1136 This paper represents the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Statistics Canada. Recent immigration and the formation of visible minority neighbourhoods in Canada’s large cities by Feng Hou 11F0019MIE No. 221 ISSN: 1205-9153 ISBN: 0-662-37031-7 Business and Labour Market Analysis Division 24-F, R.H. Coats Building, Ottawa, K1A 0T6 Statistics Canada How to obtain more information : National inquiries line: 1 800 263-1136 E-Mail inquiries: [email protected] July 2004 A part of this paper was presented at the conference on Canadian Immigration Policy for the 21st Century, October 18-19, 2002, Kingston, Ontario. Many thanks to Eric Fong, Mike Haan, John Myles, Garnett Picot, and Jeff Reitz for their constructive comments and suggestions. This paper represents the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Statistics Canada. Published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada © Minister of Industry, 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission from Licence Services, Marketing Division, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0T6. -

The Ideology of a Hot Breakfast

The ideology of a hot breakfast: A study of the politics of the Harris governent and the strategies of the Ontario women' s movement by Tonya J. Laiiey A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Studies in confonnity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada May, 1998 copyright 8 Tonya J. Lailey. 1998 National Library Bibl&th$aue nationaie of Canada du Cana uisitions and Acquisitions et "iBb iographk SeMces services bibliographiques 395 Wdîîngton Street 305, nie Wellington OttamON KlAONI OttawaON K1AW Canada Cenada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibiiotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, clistriiute or sel reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retahs ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This is a study of political strategy and the womn's movement in the wake of the Harris govemment in Ontario. Through interviewhg feminist activists and by andyzhg Canadian literature on the women's movement's second wave, this paper concludes that the biggest challenge the Harris govenunent pnsents for the women's movement is ideological. -

George Committees Party Appointments P.20 Young P.28 Primer Pp

EXCLUSIVE POLITICAL COVERAGE: NEWS, FEATURES, AND ANALYSIS INSIDE HARPER’S TOOTOO HIRES HOUSE LATE-TERM GEORGE COMMITTEES PARTY APPOINTMENTS P.20 YOUNG P.28 PRIMER PP. 30-31 CENTRAL P.35 TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR, NO. 1322 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2016 $5.00 NEWS SENATE REFORM NEWS FINANCE Monsef, LeBlanc LeBlanc backs away from Morneau to reveal this expected to shed week Trudeau’s whipped vote on assisted light on deficit, vision for non- CIBC economist partisan Senate dying bill, but Grit MPs predicts $30-billion BY AbbaS RANA are ‘comfortable,’ call it a BY DEREK ABMA Senators are eagerly waiting to hear this week specific details The federal government is of the Trudeau government’s plan expected to shed more light on for a non-partisan Red Cham- Charter of Rights issue the size of its deficit on Monday, ber from Government House and one prominent economist Leader Dominic LeBlanc and Members of the has predicted it will be at least Democratic Institutions Minister Joint Committee $30-billion—about three times Maryam Monsef. on Physician- what the Liberals promised dur- The appearance of the two Assisted ing the election campaign—due to ministers at the Senate stand- Suicide, lower-than-expected tax revenue ing committee will be the first pictured at from a slow economy and the time the government has pre- a committee need for more fiscal stimulus. sented detailed plans to reform meeting on the “The $10-billion [deficit] was the Senate. Also, this is the first Hill. The Hill the figure that was out there official communication between Times photograph based on the projection that the the House of Commons and the by Jake Wright economy was growing faster Senate on Mr. -

REPORT of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada

Canada REPORT OF THE Chief Electoral Officer of Canada Following the June 30, 2014, By-elections Held in Fort McMurray–Athabasca, Macleod, Scarborough–Agincourt and Trinity–Spadina and the November 17, 2014, By-elections Held in Whitby–Oshawa and Yellowhead EC 94366 (03/2015) Canada REPORT OF THE Chief Electoral Officer of Canada Following the June 30, 2014, By-elections Held in Fort McMurray–Athabasca, Macleod, Scarborough–Agincourt and Trinity–Spadina and the November 17, 2014, By-elections Held in Whitby–Oshawa and Yellowhead For enquiries, please contact: Public Enquiries Unit Elections Canada 30 Victoria Street Gatineau, Quebec K1A 0M6 Tel.: 1-800-463-6868 Fax: 1-888-524-1444 (toll-free) TTY: 1-800-361-8935 www.elections.ca SE1-2/2014-3E-PDF 978-1-100-25733-4 © Chief Electoral Officer of Canada, 2015 All rights reserved Printed in Canada Le directeur général des élections • The Chief Electoral Officer March 31, 2015 The Honourable Andrew Scheer, M.P. Speaker of the House of Commons Centre Block House of Commons Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6 Dear Mr. Speaker: I have the honour to provide my report following the by-elections held on June 30, 2014, in the electoral districts of Fort McMurray–Athabasca, Macleod, Scarborough–Agincourt and Trinity–Spadina, and on November 17, 2014, in the electoral districts of Whitby–Oshawa and Yellowhead. I have prepared the report in accordance with subsection 534(2) of the Canada Elections Act, S.C. 2000, c. 9. Under section 536 of the Act, the Speaker shall submit this report to the House of Commons without delay. -

VISIBLE MINORITIES — Equity and Inclusion Lens

Diversity Snapshot VISIBLE MINORITIES — Equity and Inclusion Lens Diversity Snapshot VISIBLE MINORITIES We are diverse, and the fastest-growing population sector in Ottawa. One third of us are Canadians by birth and our families have been part of building Ottawa for more than a century. We are grouped together for being nonwhite, but in reality, we are a rich mix of ethnic origins and cultures from as many as 100 different nationalities. 1. Who we are . 3 2. Contributions we make . 4 3. Barriers and inequities. 5 1) Attitudes. 5 2) Stereotypes. 5 3) Denial of racism. 6 4) Income . 6 5) Employment . 7 6) Advancement opportunities. 7 7) Workplace harassment . 7 8) Racial profiling. 8 9) Housing and neighbourhood . 9 10) Civic and political engagement. 9 4. We envision – a racism-free city. 10 What can I do?. 10 5. Council mandates and legislation. 11 6. What’s happening in Ottawa. 11 7. Relevant practices in other cities. 12 8. Sources. 12 9. Definitions. 13 10. Acknowledgements . 15 This document is one of 11 Diversity Snapshots that serve as background information to aid the City of Ottawa and its partners in implementing the Equity and Inclusion Lens. To access, visit Ozone or contact us at [email protected]. A City for Everyone — 2 Diversity Snapshot VISIBLE MINORITIES — Equity and Inclusion Lens 1. Who we are IN OTTAWA We are diverse, and the fastest-growing population sector in Ottawa (SPC 2008-a). Many of us (32.8 per Ottawa has the second cent) are Canadians by birth and our families have been highest proportion of visible part of building Ottawa for over 100 years (SPC 2008-b). -

Curriculum Vitae Graham White

CURRICULUM VITAE GRAHAM WHITE Professor Emeritus of Political Science University of Toronto Mississauga Revised October 2015 Department of Political Science University of Toronto at Mississauga Mississauga, Ontario L5L 1C6 (905) 569-4377/ (416) 978-6021 FAX: (905-569-4965)/ (416) 978-5566 e-mail: [email protected] Education B.A. Economics and Political Science, York University, 1970 M.A. Political Science, McMaster University, 1971 Ph.D. Political Science, McMaster University, 1979 Thesis: “Social Change and Political Stability in Ontario: Electoral Forces 1867-1977” (Supervisor: Prof. H.J. Jacek) Work 1970-74 Teaching Assistant, McMaster University Experience 1974-76 Part-time sessional lecturer, York University 1976-77 Ontario Legislative Intern 1977-78 Visiting Assistant Professor, Glendon College 1978-84 Assistant Clerk, Legislative Assembly of Ontario 1984-92 Assistant Professor, Erindale College, University of Toronto 1992-95 Associate Professor, Erindale College, University of Toronto 1995-2015 Professor, University of Toronto Mississauga 2015 - Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Mississauga Appointed to graduate faculty 1985 Awarded tenure 1992 Languages: English: fluent French: limited Curriculum Vitae - Graham White – October 2015 2 GRANTS 2015-20 Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Partnership Grant, “Tradition and Transition among the Labrador Inuit” (Co-investigator with Professor Christopher Alcantara, Western University), $120,000. 2008-12 Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council -

Federation of Ontario Public Libraries, CEO's Report to Members, June, 2012

CEO’s Report to Members June 2012 This report outlines the activities of the Federation over the past four months. Meetings with Government Officials The Federation continues to meet with various politicians and bureaucrats to address our key advocacy issues. During the past few months, meetings were held with: Mike Maka, Special Assistant on Policy to Harinder Takhar, Minister of Government Seervices (16Feb2012) David Black, Senior Policy Advisor to Bob Chiarelli, Minister of Infrastructure & Transportation (21Feb2012) Paul Miller, MPP for Hamilton East-Stoney Creek and NDP Culture Critic (23Feb2012) Melanie Wright, Senior Policy Advisor to Dwight Duncan, Minister of Finance (23Feb2012) Brad Duguid, Minister of Economic Development & Innovation (23Mar2012) Emilee Irwin, Senior Policy Advisor to Laurel Broten, Minister of Education (11Apr2012) Taki Sarantakis, Assistant Deputy Minister, Policy & Communications Branch of Infrastructure Canada (06Jun2012) Ontario and Federal Budgets There was no specific mention of public libraries in the Ontario Budget announced on March 27, 2012. However, the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport, like most ministries, is planning to reduce spending over the next three years. The Ministry is planning to cut $11 million ($3.0 M in 2012/13, $4.0 M in 2013/14, and $4.0 in 2014/15) by removing overlap and duplication. This will largely come from consolidating four existing grant programs (ie. Museum and Technology Fund, International Cultural Initiatives Fund, Creative Communities Prosperity Fund, and Cultural Strategic Investment Fund). The Ministry is planning additional unspecified reductions of $14.4 million ($0.5 M in 2012/13, $1.5 M in 2013/14, and $12.4 M in 2014/15) by undertaking efficiency measures across various programs, including those arising as a result of the merger of the Sport program.