Edward Sorin'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When People Recognize Truth, They Become Peacemakers, Says Pope

50¢ January 8, 2006 Volume 80, No. 2 www.diocesefwsb.org/TODAY Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend ’’ TTODAYODAY SS CCATHOLICATHOLIC Religious life A look at life from the When people recognize truth, they seminary to the vocation Pages 9-15 become peacemakers, says pope God’s loving gaze BY CINDY WOODEN and concern on unborn life VATICAN CITY (CNS) — When people recognize the truth that they are all children of God and that Pope speaks of moral law exists for the benefit of all, they become peacemakers, Pope Benedict XVI said. embryonic life “Peace — this great aspiration in the heart of Page 3 every man and woman — is built day by day with the support of everyone,” the pope said Jan. 1 as he celebrated Mass for the feast of Mary, Mother of God and for World Peace Day. The Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica and the recitation Bishop blesses of the Angelus afterward in St. Peter’s Square fea- tured people from around the world dressed in their radio station native costumes. Many carried peace banners. During the Mass, the offertory gifts were given to Catholic radio station Pope Benedict by two boys and a girl from Germany is first in northeast Indiana dressed as the Magi and participants from Mexico, Peru, Pakistan, Vietnam and Democratic Republic of Page 6 Congo. In the prayers — read in Russian, Chinese, Arabic, Polish, Spanish and Portuguese — the con- gregation asked God to help the churches of the East and West work together for peace and asked God to Sound and bless international organizations committed to peacemaking. -

Campus Throughout Their Lives Lives Their Throughout Campus to Back Come Also Alumni These Of

home to the Hagerty Family Café, Modern Market, and Star Ginger. Star and Market, Modern Café, Family Hagerty the to home attended the University. the attended s parent whose students ) ( Open to the public, the Duncan Student Center is is Center Student Duncan the public, the to Open 1254 4F FAST FOOD. FOOD. FAST family. About one-quarter of undergraduate students are “legacy” “legacy” are students undergraduate of one-quarter About family. POINTS OF INTEREST —places like the Notre Notre the like —places area metropolitan the throughout places weddings and baptisms, and for other reasons tied to the Notre Dame Dame Notre the to tied reasons other for and baptisms, and weddings Subway, Taco Bell/Pizza Hut, and a mini-mart. a and Hut, Bell/Pizza Taco Subway, Notre Dame’s presence extends to to extends presence Dame’s Notre south. the to miles two about for reunions, football weekends, spiritual milestones such as as such milestones spiritual weekends, football reunions, for Center is open to the public and houses Smashburger, Starbucks, Starbucks, Smashburger, houses and public the to open is Center neighbors and neighborhoods. South Bend’s downtown is is downtown Bend’s South neighborhoods. and neighbors BASILICA OF THE SACRED HEART. 3E basilica.nd.edu GROTTO OF OUR LADY OF LOURDES. 3E of these alumni also come back to campus throughout their lives lives their throughout campus to back come also alumni these of Open seven days a week, LaFortune Student Student LaFortune week, a days seven Open 1012 4E FAST FOOD. FOOD. FAST Our life as a community is integrated with the life of our our of life the with integrated is community a as life Our Consecrated in 1888, this is the center of Catholic liturgy and worship A 1/7-scale replica of the renowned Marian apparition site in France, participate in a worldwide network of Notre Dame clubs. -

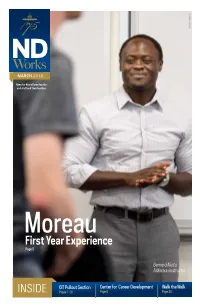

First Year Experience Page 5

NOTRE DAME NOTRE DAME NOTRE DAME NOTRE DAME BARBARA JOHNSTON NDND MARCH 2018 News for Notre Dame faculty and staff and their families Moreau First Year Experience Page 5 Bernard Akatu A Moreau instructor OIT Pullout Section Center for Career Development Walk the Walk INSIDE Pages 7-10 Page 6 Page 16 2 | NDWorks | March 2018 NEWS MATT CASHORE MATT MATT CASHORE MATT PHOTO PROVIDED BARBARA JOHNSTON BRIEFS BARBARA JOHNSTON WHAT’S GOING ON ICEALERT SIGN INSTALLED BY Nucciarone Corcoran Seabaugh Haenggi Kamat STAIRS IN GRACE/VISITOR LOT A color-changing IceAlert sign, intended to make pedestrians aware areas of the University, including innovation in creating or facilitating pastoral leadership development of of icy or slick conditions on the Notre Dame Research, the IDEA outstanding inventions that have CAMPUS NEWS lay ministers early in their careers. stairs, walkway or parking lot, has Center, University Relations and made a tangible impact on quality of been installed along the staircase to the Office of Public Affairs and Com- life, economic development and wel- BREITMAN AND BREITMAN- NANOVIC INSTITUTE AWARDS the Grace Hall/Visitor parking lot munications, to positively affect both fare of society.” JAKOV NAMED 2018 DRIEHAUS LAURA SHANNON PRIZE TO south of Stepan Center. The color on the South Bend-Elkhart region and PRIZE LAUREATES ‘THE WORK OF THE DEAD’ the University. the sign transitions from gray to blue CORCORAN APPOINTED Marc Breitman and Nada The Nanovic Institute for Euro- whenever temperatures dip below EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF Breitman-Jakov, Paris-based architects pean Studies has awarded the 2018 freezing. NUCCIARONE TO SERVE ON THE KROC INSTITUTE known for improving cities through Laura Shannon Prize in Contempo- HIGHER EDUCATION Erin B. -

Blessed Father Basil Moreau Takes Place in Diocese Pages 10-13 Holy Cross Religious Gather in France for Beatification of Their Founder

50¢ September 30, 2007 Volume 81, No. 35 Red Mass www.diocesefwsb.org/TODAY Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend TTODAYODAY’’SS CCATHOLICATHOLIC Mass for legal professionals Blessed Father Basil Moreau takes place in diocese Pages 10-13 Holy Cross religious gather in France for beatification of their founder BY SISTER MARGIE LAVONIS, CSC Indulgence LE MANS, FRANCE — A spirit of joyful anticipation Jubilee Year plenary permeated the environment when hundreds of Holy indulgence extended Cross religious and their colleagues from around the world gathered in Le Mans, France, from Sept. 14-16 Page 2, 4 to celebrate the beatification of their founder, Father Basil Anthony Moreau. The beatification festivities began on Sept. 14, the feast of the Exultation of the Holy Cross. Members of the Holy Cross family and other guests gathered in Memorial feast day front of the parish church in Laigné-en-Belin, the birth- place of Father Moreau. In his opening comments, Oct. 3 dedicated to Holy Cross Father Jean-Guy Vincent, from the St. Mother Theodore Guérin Canadian province of Holy Cross, said, “What could be more fitting for us, the sons and daughters of Basil Page 5 Moreau to gather here to launch the beatification cele- bration?” He spoke of the 60 years that the four congregations of Holy Cross worked to present his cause and said that “after a long and careful examination of the life, activ- Voice from ity and writings of Father Moreau, he was declared venerable by Pope John Paul II, April 12, 2003, and on the congress April 28, 2006, Pope Benedict XVI announced the Eucharistic Congress beatification for Sept. -

Bibliography of Holy Cross Sources

Bibliography of Holy Cross Sources General Editor: Michael Connors, C.S.C. University of Notre Dame [email protected] Contributors: Sean Agniel Jackie Dougherty Marty Roers Updated June 2007 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO LOCATION OF ITEMS iii EDITOR’S FOREWORD iv I. FOUNDERS 1-12 A. JACQUES DUJARÍE 1 B. BASIL MOREAU 3 C. MARY OF THE SEVEN DOLORS (LEOCADIE GASCOIN) 12 II. BLESSED 13-20 A. ANDRE (ALFRED) BESSETTE 13 B. MARIE LEONIE PARADIS 20 III. BIOGRAPHIES 21-42 A. BROTHERS 21 B. PRIESTS 30 C. SISTERS 38 D. OTHERS 42 IV. GENERAL HISTORIES 43-60 A. GENERAL ADMINISTRATION` 43 B. INDIVIDUAL COUNTRIES and REGIONS 45 V. PARTICULAR HISTORIES 61-96 A. UNITED STATES 61 B. WORKS OF EDUCATION 68 C. PASTORAL WORKS 85 D. HEALTH CARE SERVICES 89 E. OTHER MINISTRIES 91 VI. APPENDIX OF INDIVIDUAL BIOGRAPHY NAMES 97-99 ii iii KEY TO LOCATION OF ITEMS: CF = Canadian Brothers’ Province Archives CP = Canadian Priests’ Province Archives EB = Eastern Brothers' Province Archives EP = Eastern Priests' Province Archives IP = Indiana Province Archives KC = King’s College Library M = Moreau Seminary Library MP = Midwest Province Archives MS = Marianite Sisters’ Province Archives, New Orleans, LA ND = University of Notre Dame Library SC = Stonehill College Library SE = St. Edward's University Library SHCA = Sisters of the Holy Cross Archives SM = St. Mary’s College Library SW = South-West Brothers’ Province Archives UP = University of Portland Library iii iv EDITOR’S FOREWORD In 1983 I compiled a “Selected Bibliography, Holy Cross in the U.S.A.,” under the direction of Fr. -

Notre Dame Interest

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID NOTRE DAME, IN PERMIT NO. 10 NOTRE DAME INTEREST UNIVERSITY OF 2020 NOTRE CONNECT WITH US ON: DAME Visit us online at: undpress.nd.edu PRESS UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME PRESS The University of Notre Dame A History Thomas E. Blantz C.S.C. Summary Thomas Blantz’s monumental The University of Notre Dame: A History tells the story of the renowned Catholic university’s growth and development from a primitive grade school and high school founded in 1842 by the Congregation of Holy Cross in the wilds of northern Indiana to the acclaimed undergraduate and research institution it became by the early twenty-first century. Its growth was not always smooth—slowed at times by wars, financial challenges, fires, and illnesses. It is the story both of a successful institution and of the men and women who made it so: Father Edward Sorin, the twenty-eight-year-old French priest and visionary founder; Father William Corby, later two-term Notre Dame president, who gave absolution to the soldiers of the Irish Brigade at the Battle of Gettysburg; the hundreds of Holy Cross brothers, sisters, and priests whose faithful service in classrooms, student residence halls, and 9780268108212 across campus kept the university progressing through difficult years; a dedicated lay Pub Date: 8/31/2020 faculty teaching too many classes for too few dollars to assure the university would $49.00 survive; Knute Rockne, a successful chemistry teacher but an even more successful Hardcover football coach, elevating Notre Dame to national athletic prominence; Father Theodore 752 Pages M. -

Congregation of Holy Cross United States Province of Priests and Brothers

Congregation of Holy Cross United States Province of Priests and Brothers Name Title Address City State Zip Phone Fax E-Mail Please add my address to your mailing list. Please sign me up to receive the bi-monthly Update e-mail newsletter to stay connected to Holy Cross. (Your email address will only be used by Holy Cross; we do not share your information with other organizations.) I’m interested in learning more about: A vocation with Holy Cross International missions Ministries in the United States Thank you for your interest in the Congregation of Holy Cross. Visit us online at HolyCrossUSA.org. Ave Crux Spes Unica Hail the Cross, Our Only Hope The motto of the congregation is Ave Crux, Spes Unica, which means “Hail the Cross, Our Only Hope” — calling on the community to “learn how even the Cross can be borne as a gift.” The symbolic cross and anchors are a “coat of arms” which embodies the ancient Christian symbol of hope, the anchor, with the Cross, creating a simple but powerful representation of our motto. Office of Development P.O. Box 765 Notre Dame, IN 46556-0765 (574) 631-6731 [email protected] HolyCrossUSA.org Office of Development P.O. Box 765 Notre Dame, IN 46556-0765 (574) 631-6731 [email protected] HolyCrossUSA.org Who We Are Fr. StephenKoeth,C.S.C.,NateWills,andPeterPacini,C.S.C. Educators The United States Province of Holy Cross Priests and Brothers is a family of about 500 religious – including men in formation. We live and work in communities large and in the Faith small. -

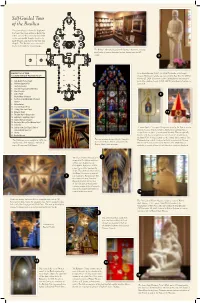

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13 This tour takes you from the baptismal 14 font near the main entrance, down the 12 center aisle to the sanctuary, then right to the east apsidal chapels, back to the 16 15 11 Lady Chapel, and then to the west side chapels. The Basilica museum may be 18 17 7 10 reached through the west transept. 9 The Bishops’ Museum, located in the Basilica’s basement, contains pontificalia of various American bishops, dating from the 19th century. 11 6 5 20 19 8 4 3 BASILICA OF THE Saint André Bessette, C.S.C. (1845-1937), founder of St. Joseph’s SACRED HEART FLOOR PLAN Oratory, Montréal, Canada, was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI on October 17, 2010. The statue of Saint André Bessette was designed 1. Font, Ambry, Paschal Candle by the Rev. Anthony Lauck, C.S.C. (1985). Saint André’s feast day is 2. Holtkamp Organ (1978) 8 January 6. 3. Sanctuary Crossing 2 4. Seal of the Congregation of Holy Cross 1 5. Altar of Sacrifice 6. Ambo (Pulpit) 9 7. Original Altar / Tabernacle 8. East Transept and World War I Memorial Entrance 9. Tintinnabulum 10. St. Joseph Chapel (Pietà) 11. St. Mary / Bro. André Chapel 2 12. Reliquary Chapel 17 13. The Lady Chapel / Baroque Altar 14. Holy Angels / Guadalupe Chapel 15. Mural of Our Lady of Lourdes 16. Our Lady of Victory / Basil Moreau Chapel 17. Ombrellino 18. Stations of the Cross Chapel / Tomb of A “minor basilica” is a special designation given by the Pope to certain John Cardinal O’Hara, C.S.C. -

Notre Dame Athletics Department

NOTRE DAME WELCOME TO NOTRE DAME The interior of the golden-domed Main Building on the Notre Dame campus was closed for the 1997-99 academic years as it underwent a renovation. The facility was rededicated in ceremonies in August of ’99. It also underwent a $5 million exterior renovation, which included the cleaning and repair of the 4.2 million bricks of the facility, in 1996. The University of Notre Dame decided, however, was precisely the type of institution Notre Dame would become. How could this small Midwestern school without endowment and without ranks of well-to-do alumni hope to compete with firmly established private universities and public-sup- ported state institutions? As in Sorin’s day, the fact that the University pursued this lofty and ambitious vision of its future was testimony to the faith of its leaders — leaders such as Father John Zahm, C.S.C. As Schlereth describes it: “Zahm… envisioned Notre Dame as potentially ‘the intellectual center of the American West’; an institu- tion with large undergraduate, graduate, and profes- sional schools equipped with laboratories, libraries, and research facilities; Notre Dame should strive to become the University that its charter claimed it was.” Zahm was not without evidence to support his faith in Notre Dame’s potential. On this campus in 1899, Jerome Green, a young Notre Dame scientist, became Notre Dame’s founding can perhaps best be charac- University’s academic offerings. While a classical col- the first American to transmit a wireless message. At terized as an outburst -

Ordinations 2012 2 CHOICES Putting the Work of Building God’S Kingdom First Fr

CHOICESFROM THE CONGREGATION OF HOLY CROSS OFFICE OF VOCATIONS VOLUME 33, ISSUE 2 IN THIS ISSUE: Ordinations 2012 2 CHOICES Putting the Work of Building God’s Kingdom First Fr. Matthew C. Kuczora, C.S.C. Ever since he became a deacon, and now a priest, Fr. Matthew The Holy Cross Vocations Team: Fr. Jim Gallagher, C.S.C., and Fr. Drew Gawrych, C.S.C. Kuczora’s fantasy football team has For many years now, we in Holy Cross have celebrated the Ordinations of taken a serious dive. many of our priests on Easter Saturday, placing this special event in the He is on the staff of life of our community right in the midst of the Church’s celebration of the a parish in México, so Sunday has become a busy day resurrection of our Savior, Jesus Christ. Our celebration, then, is not merely for him. His work with seminarians in México also about men receiving the Sacrament of Holy Orders (a reason for rejoicing means that he gets up early and goes to bed late. He in its own right); it becomes a part of the Church’s greater celebration of just does not have the time and energy to follow the the saving mystery of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection. NFL like he once did. For the one receiving the Sacrament of Holy Orders, it is a moment in And it is not only Ray Lewis that he misses from which he continues the offer made in his Final Vows to place his life in his life as a college student. -

Ain^Cbolastlc

.{:i.::^:;c'->- •^•.... ain^cbolastlc .>:5: ,^<x DISCEQUASISEMPER-VICTVRVS VIVE-QUASI-CRASMORITVRVS VOL. LI. NOTRE DAME, INDIANA, SEPTEMBER 29, 1917 No I. [This issue of the "Scholastic" contains, besides the spirit to admiring auditors, and looked as if a special articles on the Diamond Jubilee, a number of century was not too much for his present vitality. excerpts from letters, telegrams, and comments of the. Press on that occasion, too numerous and lengthy to People made a distinction in talking about him.; ptiblish complete.] When they said "the Cardinal," they meant James Gibbons. Other Cardinals were meuT Digmcnd Jubilee of Notre Dame University. tioned by their siu-names. Two ordinary alumnf of Notre Dame were watching the procession BY JOHN TALBOT SMITH. into the Church on Sunday, June 10, and were deeply interested in the spectacle of Cardinal <^f^HE great advantage of Notre Dame. Gibbons walking under the canopy arotmd the in its public celebrations is the noble grounds on his way to the solemn pontifical il extent and gracious character of its Mass. When the procession had :vanished location. No nobler stage could be within the portals one alumnus said to the found as the setting of a noble drama. other: k The immense quadrangle fronting the main •'Grand old man. outlived everybody. buildings, with trees and shrubs in abun- eighty-three this month,^and walks all over the. I" dance, is only one feature of the scene. Left grounds fasting, and has to say Mass yet, k and right are other quadrangles and spacious and sit out the whole ceremony, and looks as- 1/ lawns'; in the rear and to the west lie the. -

Christian Education by Bl. Basil Moreau

Christian Education By Blessed Basil Anthony M. Moreau The Holy Cross Institute AT ST. EDWARD’S UNIVERSITY Editor’s Note First published in 1856, Christian Education is a manuscript by Reverend Basil Anthony M. Moreau, founder of the Congregation of Holy Cross. In this manuscript, Father Moreau attempted to outline the ideals and the goals of a Holy Cross education as he saw them. These ideals were used in setting up the school in Le Mans, France, that bore the name Our Lady of Holy Cross. Part One of the original text, Teachers and Students, is presented in its entirety. Part Two, dealing with the establishment of a school in the France of Father Moreau’s day, provides practical guidelines for maintaining a school and directives regarding content and instruction. This edition includes brief excerpts from the final part (the only difference from the earlier version), which deals with the teaching of religion and the Christian formation of students. Grateful acknowledgement is made to the South-West Province, Congregation of Holy Cross for making Christian Education available in English to the Congregation, and in particular to Brother Edmund Hunt, CSC, for the initial translation, completed in 1986. That edition was ably edited by Brother Franklin Cullen, CSC, and Brother Donald Blauvelt, CSC. The new excerpts included in this edition are from a subsequent translation of Christian Education by Sister Anna Teresa Bayhouse, CSC, completed in December 2002. To this sesquicentennial edition of Christian Education are appended a readers’ guide and materials for further reflection. Grateful acknowledgement goes to the contributions of Brother Joel Giallanza, CSC, Brother Thomas Dziekan, CSC, and Brother Robert Lavelle, CSC, in the preparation of these latter materials.