Making It: Inside Perceptions on Success, Relapse, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PREA) Audit Report Adult Prisons & Jails

Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) Audit Report Adult Prisons & Jails ☐ Interim ☒ Final Date of Report January 15, 2021 Auditor Information Name: Darla P. O’Connor Email: [email protected] Company Name: PREA Auditors of America Mailing Address: 14506 Lakeside View Way City, State, Zip: Cypress, TX Telephone: 225-302-0766 Date of Facility Visit: December 1-2, 2020 Agency Information Name of Agency: Governing Authority or Parent Agency (If Applicable): Texas Department of Criminal Justice State of Texas Physical Address: 861-B I-45 North City, State, Zip: Huntsville, Texas 77320 Mailing Address: PO Box 99 City, State, Zip: Huntsville, Texas 77342 The Agency Is: ☐ Military ☐ Private for Profit ☐ Private not for Profit ☐ Municipal ☐ County ☒ State ☐ Federal Agency Website with PREA Information: https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/tbcj/prea.html Agency Chief Executive Officer Name: Bryan Collier Email: [email protected] Telephone: 936-437-2101 Agency-Wide PREA Coordinator Name: Cassandra McGilbra Email: [email protected] Telephone: 936-437-5570 PREA Coordinator Reports to: Number of Compliance Managers who report to the PREA Coordinator Honorable Patrick O’Daniel, TBCJ Chair 6 PREA Audit Report – V5. Page 1 of 189 Jester Complex, Richmond, TX Facility Information Name of Facility: Jester Complex Physical Address: 3 Jester Road City, State, Zip: Richmond, TX 77406 Mailing Address (if different from above): Jester 2 (Vance) 2 Jester Road City, State, Zip: Richmond, TX 77406 The Facility Is: ☐ Military ☐ Private for Profit ☐ Private not for Profit ☐ Municipal ☐ County ☒ State ☐ Federal Facility Type: ☒ Prison ☐ Jail Facility Website with PREA Information: https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/tbcj/prea.html Has the facility been accredited within the past 3 years? ☒ Yes ☐ No If the facility has been accredited within the past 3 years, select the accrediting organization(s) – select all that apply (N/A if the facility has not been accredited within the past 3 years): ☒ ACA ☐ NCCHC ☐ CALEA ☐ Other (please name or describe: Click or tap here to enter text. -

Texas Department of Criminal Justice Rehabilitation Programs Division Department Report August 2012

Texas Department of Criminal Justice Rehabilitation Programs Division Department Report August 2012 CHAPLAINCY Manager III Department or Program Head: Phone #: Marvin Dunbar Bill Pierce and Richard Lopez (936) 437-3028 MISSION The mission of the Chaplaincy Department of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) is to positively impact public safety and the reduction of recidivism through the rehabilitation and re-integration of adult felons into society. This is accomplished by the availability of comprehensive pastoral care, by the management of quality programming, and through the promotion of therapeutic religious community activities. It is the purpose of Chaplaincy to provide guidance and nurture to those searching for meaning in life and to those offenders who are in transition. Programs, activities, and community participation are prudently managed wherein individuals have an opportunity to pursue religious beliefs, reconcile relationships, and strengthen the nuclear family. AUTHORITY Administrative Directive: AD 07.30 (rev. 6) Chaplaincy services shall be provided within TDCJ operated units or contracted facilities in order to serve offenders who desire to practice elements of their religion. It is the policy of TDCJ to extend to offenders of all faiths, reasonable and equitable opportunities to pursue religious beliefs and participate in religious activities and programs that do not endanger the safe, secure and orderly operation of the Agency. Participation in all religious activities and attendance at religious services of worship is strictly voluntary. No employee, contractor or volunteer shall disparage the religious beliefs of any offender or compel any offender to make a change of religious preference. Chaplaincy services shall strive to assist offenders who desire to incorporate religious beliefs and practices into a process for positive change in personal behaviors by offering meaningful, rehabilitative religious programming as an important tool for successful reintegration into society. -

The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation National Honor Guard

CPO FAMILY Autumn 2017 A Publication of The CPO Foundation Vol. 27, No. 2 The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation National Honor Guard To see the CPOF National Honor Guard members “up close and personal,” go to pages 24-25. Bravery Above and Beyond the Call of Duty See page 20 for the inspiring stories of these three life-saving Corrections Professionals whose selfless acts of Sgt. Mark Barra bravery “off the job” Calipatria State Prison, CA earned them much- Lt. John Mendiboure Lt. Christopher Gainey deserved recognition at Avenal SP, CA Pender Correctional Project 2000 XXVIII. Institution, NC Inside, starting on page 4: PROJECT 2000 XXVIII ~ June 15-18, 2017, San Francisco, CA 1 Field Representatives CPO FAMILY Jennifer Donaldson Davis Alabama Carolyn Kelley Alabama The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation Ned Entwisle Alaska 1346 N. Market Blvd. • Sacramento, CA 95834 Liz Shaffer-Smith Arizona P. O. Box 348390 • Sacramento, CA 95834-8390 Annie Norman Arkansas 916.928.0061 • 800.800.CPOF Connie Summers California cpof.org Charlie Bennett California Guy Edmonds Colorado Directors of The CPO Foundation Kim Blakley Federal Glenn Mueller Chairman/National Director George Meshko Federal Edgar W. Barcliff, Jr. Vice Chairman/National Director Laura Phillips Federal Don Dease Secretary/National Director John Williams Florida Richard Waldo Treasurer/National Director Donald Almeter Florida Salvador Osuna National Director Jim Freeman Florida Jim Brown National Director Vanessa O’Donnell Georgia Kim Potter-Blair National Director Rose Williams -

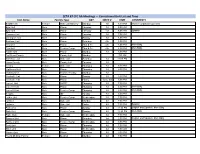

SETA 67 CFC AA Meetings -- Correctional Unit List and Time

SETA 67 CFC AA Meetings -- Correctional Unit List and Time Unit Name Facility Type DAY WEEK # TIME COMMENTS BAMBI Unit Female State Jail Nursery Monday All 6:30 PM Women only/babies present Byrd Unit Male Prison Tuesday All 6:00 PM Byrd Unit Male Prison Tuesday 1st 6:00 PM Spanish Clemens Unit Male Prison Tuesday All 7:00 PM Darrington Unit Male Prison Sunday All 6:00 PM Eastham Unit Male Prison Saturday 4th 3:00 PM Ellis Unit Male Prison Thur & Fri 4th 5:00 PM Main Bldg. Ellis Unit Male Trustee Camp Thur & Fri 4th 6:30 PM Main Bldg. Estelle Unit Male Prison Monday All 6:00 PM Fort Bend County Male County Jail Monday 930 AM Gist State Jail Male State Jail Saturday All 12:00 PM Harris County Male County Jail Tuesday All Henley Female State Jail Thursday All 7:30 PM Hightower Unit Male Prison Thursday All 6:00 PM Holliday Unit Male Transfer Facility Monday All Huntsville Unit Male Prison Sunday All 2:30 PM Huntsville Unit Male Prison Friday 1st & 3rd 6:00 PM Jester I Unit Male SAFPF Thursday All 7:00 PM Jester III Unit Male Prison Thursday All 6:30 PM Main Bldg Jester III Unit Male Trustee Camp Thursday All 6:30 PM Main Bldg. Kegans Male ISF Tueday All 6:30 PM Luther Unit Male Trustee Camp Wednesday All 7:00 PM Lychner Male State Jail Monday All 7:00 PM Lychner Male State Jail Friday All 7:00 PM Spanish Pack Unit Male Prison Sunday All 12:30 PM English and Spanish, Main Bldg. -

Texas Department of Criminal Justice

VOLUNTEER TRAINING SCHEDULE Please choose a training site that is most convenient to attend. You are required to contact the facility prior to the training to verify no schedule changes have occurred and to ensure you are on the Volunteer Training Roster. Please wear proper attire. You DO NOT need a letter from Volunteer Services to attend this training. Attending this training does not guarantee you will be approved. If you are concerned about your eligibility you are encouraged to contact Volunteer Services prior to attending. What to Bring: driver’s license, pen, completed Volunteer application For additional information regarding the TDCJ Volunteer Program contact Volunteer Services at 936-437-3026 ABILENE, TEXAS AUSTIN, TEXAS McConnell Unit BRYAN, TEXAS Middleton Transfer Facility Diocese of Austin Pastoral 3001 S. Emily Drive Hamilton Unit Visitation Room Center Beeville, TX 78102 PRTC Bldg. Room 119 13055 FM 3522 6225 Highway 290 E (361) 362-2300 200 Lee Morrison Lane Abilene, TX 79601 Austin, TX 78723 01/21/16 9:00am – 1:00pm Bryan, TX 77807 (325) 548-9075 (512) 926-4482 04/21/16 9:00am – 1:00pm (979) 779-1633 05/14/16 1:00pm – 5:00pm 01/09/16 12:00pm – 4:00pm 07/21/16 9:00am – 1:00pm 03/05/16 9:00am – 1:00pm 08/20/16 1:00pm – 5:00pm 04/09/16 12:00pm – 4:00pm 10/20/16 9:00am – 1:00pm 06/04/16 9:00am – 1:00pm 11/19/16 1:00pm – 5:00pm 07/16/16 12:00pm – 4:00pm 09/03/16 9:00am – 1:00pm BONHAM, TEXAS 12/03/16 9:00am – 1:00pm Robertson Unit St. -

Needs Related to Regional Medical Facilities for TDCJ

Needs Related to Regional Medical Facilities for TDCJ A Study Submitted in Response to Rider 78, TDCJ Appropriations, Senate Bill 1, 79th Legislature, 2005 Correctional Managed Health Care A Review of Needs Related to Regional Medical Facilities for TDCJ Contents Executive Summary ___________________________________________________________________________________ iv Introduction _________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Approach ___________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Key Considerations ___________________________________________________________________________________ 7 Classification and Security ____________________________________________________________________________________7 Facility Missions_____________________________________________________________________________________________9 Facility Physical Plant ________________________________________________________________________________________9 Geography__________________________________________________________________________________________________9 Current Health Care Facilities ________________________________________________________________________________10 Staffing and Support Resource Availability _____________________________________________________________________10 Key Service Population Characteristics __________________________________________________________________ 11 Inventory of Current Capabilities _______________________________________________________________________ -

ENTERED UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT February 28, 2017 SOUTHERN DISTRICT of TEXAS David J

Case 4:12-cv-01761 Document 252 Filed in TXSD on 02/28/17 Page 1 of 34 United States District Court Southern District of Texas ENTERED UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT February 28, 2017 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS David J. Bradley, Clerk HOUSTON DIVISION JAMES M. GUTHRIE, § § Plaintiff, § VS. § CIVIL ACTION NO. H-12-1761 § KOKILA NIAK, et al, § § Defendants. § MEMORANDUM AND ORDER Pending are Defendants Naik’s, Williams’s, Ahmad’s, and Dostal’s Motion for Summary Judgment (Docket Entry No. 249) and Defendants Hudspeth’s and Miller’s Motion for Summary Judgment (Docket Entry No. 251). Plaintiff James M. Guthrie has not filed a response to either motion. The Court has considered the motions, record, evidence, arguments of the parties, and applicable law, and concludes that the motions should be granted and this case should be dismissed. I. Background Plaintiff James M. Guthrie (“Plaintiff”), a former prisoner,1 filed two civil rights lawsuits under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 which have now been consolidated. See Guthrie v. Naik, Civ. A. No. H- 12-1761 (S.D. Tex. 2012) (consolidated with Guthrie v. Hudspeth, Civ. A. No. H-13-2774 (S.D. Tex. 2013)). Plaintiff claims in Naik that certain medical officials breached a settlement agreement arising out of a lawsuit Plaintiff filed in 2007 and that they violated his Eighth Amendment rights in connection with providing him medical care. Naik, Civ. A. No. H-12- 1 It is undisputed that Plaintiff is no longer incarcerated in any unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice nor under the care or control of any named Defendant. -

Area Support ID Card Stations

Texas Department of Criminal Justice Area Support ID Card Stations Below is a list of ID Card Stations providing area support. These stations shall be used only for replacement ID cards when a new photograph is required. See Section III.D.2.b.(2) of PD-03, “Employee ID Cards.” The units and offices to be supported by each station are less than 30 miles from the station. An employee shall hand carry an approved PERS 260, ID Card Issue Request to the appropriate station. The employee shall wear normal work attire when appearing at the station. ID Card Station Units and Offices Supported Human Resources Division TDCJ Headquarters 2 Financial Plaza, Suite #600 TDCJ-CID Headquarters Huntsville Windham School District Headquarters CID Region I Headquarters Byrd Eastham Ellis Estelle Ferguson Goree Holliday Huntsville Wynne Conroe Parole Office Huntsville Board of Pardons and Paroles Office Huntsville Parole Office Huntsville Institutional Parole Office Huntsville Victim Services Office TDCJ-CID Training Academy (Criminal Justice Center, Ellis and Eastham) Parole/Austin Area HR Office Austin Administrative Departments 8610 Shoal Creek TDCJ-Austin Headquarters Austin Parole HR Office TDCJ-PD Headquarters CID Region VI Headquarters TDCJ-CJAD Headquarters Austin Board of Pardons and Paroles Office Victim Services Division Headquarters Austin Parole Offices Georgetown Parole Office Travis County State Jail Kyle Unit Beeville Regional HR Office CID Region IV Headquarters Building 2040, 1st Floor TDCJ-CID Training Academy (Beeville) Chase Field Criminal -

Sunset Advisory Commission Staff Report, 1998

Sunset Advisory Commission Texas Department of Criminal Justice Board of Pardons and Paroles Correctional Managed Health Care Advisory Committee Staff Report 1998 SUNSET ADVISORY COMMISSION Members SENATOR J.E. "BUSTER" BROWN, CHAIR REPRESENTATIVE PATRICIA GRAY, VICE CHAIR Senator Chris Harris Representative Fred Bosse Senator Frank Madla Representative Allen Hightower Senator Judith Zaffirini Representative Brian McCall Robert Lanier, Public Member William M. Jeter III, Public Member Joey Longley Director In 1977, the Texas Legislature created the Sunset Advisory Commission to identify and eliminate waste, duplica- tion, and inefficiency in government agencies. The 10-member Commission is a legislative body that reviews the policies and programs of more than 150 government agencies every 12 years. The Commission questions the need for each agency, looks for potential duplication of other public services or programs, and considers new and innovative changes to improve each agency's operations and activities. The Commission seeks public input through hearings on every agency under Sunset review and recommends actions on each agency to the full Legis- lature. In most cases, agencies under Sunset review are automatically abolished unless legislation is enacted to continue them. TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE BOARD OF PARDONS AND PAROLES CORRECTIONAL MANAGED HEALTH CARE ADVISORY COMMITTEE SUNSET STAFF REPORT Table of Contents PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. -

Private Prisons in Texas

Texas Private Prisons / !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !?!? !? !?!? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !? !?!? !? 0 30 60 90 120 Miles !? !? !? !?!? Making Profit on Crime !? !? By Steve Ediger !? For Grassroots Leadership How to cite ETOPO1: Amante, C. and B. W. Eakins, ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute !? CGomlmoubniatyl E Rduecaltiieonf CMenotedrsel:!? ProCcoreredctiuonrse Cso,rp D. oaf Atmae rSicaources a!?nd ALanSalley Ssoiusth. wNesOt CAorArections !? GTEOe cGhronupical Memorand!?umM NanaEgeSmDenItS an dN TGrainDinCg C-o2rp4o,r a1tio9n p!?p, MLCaSr cChorrections 2009.<br>Hillshade visualization by J. Varner and!? E. ELmimera,l dC CoIRrreEctioSn,s University of Colorado at Boulder and NOAA/NGDC. Table of Contents and Credits Table of Contents Credits Front Cover Global Relief Introduction 1 • Amante, C. and B. W. Eakins, ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute Table of Counties/Facilities 2 Global Relief Model: Procedures, Data Sources and Angelina 6 Analysis. NOAA Technical Memorandum NESDIS Bexar 7 NGDC-24, 19 pp, March 2009 Bowie 8 • Hillshade visualization by J. Varner and E. Lim, Brooks 9 CIRES, University of Colorado at Boulder and Burnet 10 NOAA/NGDC. Caldwell 11 United States Census Bureau Concho 12 Goldberg DW. [Year]. Texas A&M University Dallas 13 Geoservices. Available online at Dickens 14 http://geoservices.tamu.edu. Ector 15 Last accessed 10/26/2012 Falls 16 Grassroots Leadership Fannin 17 United States Federal Bureau of Prisons Frio 18 Texas Department of Criminal Justice Garza 19 Harris 20 United -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

Project 2000 Xxx ~ June 6-9, 2019 Louisville, Kentucky

CPO FAMILY Autumn 2019 A Publication of The CPO Foundation Vol. 29, No. 2 PROJECT 2000 XXX ~ JUNE 6-9, 2019 LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY The 10 Fallen Officers honored at this year’s Project 2000 National Memorial Ceremony held in Louisville, Kentucky. Story starts on page four. 1 Field Representatives CPO FAMILY Jennifer Donaldson Davis Alabama Annie Norman Arkansas The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation Connie Summers California 1346 N. Market Blvd. • Sacramento, CA 95834 Charlie Bennett California P. O. Box 348390 • Sacramento, CA 95834-8390 Guy Edmonds Colorado 916.928.0061 • 800.800.CPOF Richard Loud Connecticut cpof.org Kim Blakley Federal George Meshko Federal Directors of The CPO Foundation Laura Phillips Federal Glenn Mueller Chairman/National Director Donald Almeter Florida Edgar W. Barcliff, Jr. Vice Chairman/National Director Jim Freeman Florida Don Dease Secretary/National Director Gerard Vanderham Florida Salvador Osuna National Director Vanessa O’Donnell Georgia Jim Brown Treasurer/National Director Rose Williams Georgia Kim Potter-Blair National Director Sue Davison Illinois Ronald Barnes National Director Adrain Brewer Indiana Wayne Bowdry Kentucky Chaplains of The CPO Foundation Vanessa Lee Mississippi Rev. Gary R. Evans Batesburg-Leesville, SC Ora Starks Mississippi Pastor Tony Askew Brundidge, AL Lisa Hunter Montana Tania Arguello Nevada Honor Guard Commanders of The CPO Foundation Nicholas Bunnell New Jersey Colonel/Commander Steve Dizmon (Ret.) California DOC Jay West New York Assistant Commander Raymond Gonsalves (Ret.)