The University of Oklahoma Graduate College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Bruneau and David Gordon Duke Jean Coulthard: a Life in Music

150 Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire de l’éducation BOOK REVIEWS / COMPTES RENDUS William Bruneau and David Gordon Duke Jean Coulthard: A Life in Music. Vancouver: Ronsdale, 2005. 216 pp. William J. Egnatoff She “made sense of life by composing.” (p. 146) “My aim is simply to write music that is good . to minister to human welfare . [A] composer’s musical language should be instinctive, personal, and natural to him.” (p. 157) Bruneau and Duke’s illuminating guide to the life and music of Vancouver composer Jean Coulthard (“th” pronounced as in “Earth Music” (‘cello, 1986) or “Threnody” (various choral and instrumental, 1933, 1947, 1960, 1968, 1970, 1981, 1986) con- tributes substantially and distinctively in form and detail to the growing array of biographical material on internationally-known Canadian composers of the twen- tieth century. Coulthard (1908–2000) began writing music in childhood and con- tinued as long as she could. Composition dates in the 428-page catalogue of the Coulthard manuscripts which can be found at the Web page http://www.library. ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/2007.06.27.cat.pdf, and was prepared by the authors to accompany the posthumous third accession to the composer’s archives, range from 1917 to 1997. The catalogue is housed at the University of British Columbia at the Web site http://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/coulth.html. Her works span all forms from delightful graded pieces for young piano students, through choral and chamber music, to opera and large orchestral scores. The book addresses students of Canadian classical music, women’s issues, and the performing arts. -

FEATURE | Pondering the Direction of Canadian Classical Music by Jennifer Liu on February 4, 2017

FEATURE | Pondering The Direction Of Canadian Classical Music By Jennifer Liu on February 4, 2017 150 Years of History, Another Good 150 of Innovation: A commemoration of classical music in Canada. [excerpt: see full article here: http://www.musicaltoronto.org/2017/02/04/feature-pondering-the-question- of-canadian-classical-music/] Step into the future, and we see pianist Darren Creech stepping on stage in tropical short shorts, glittery hair and a big grin on his face. But in fact, as his audiences from Montreal to Toronto have witnessed, Darren has already pulled off the dress code to rave reviews, including for his Master’s graduation recital (to which a jury panelist gushed “LOVE those legs!”) How does Darren project his many identities through music — from his Mennonite heritage, to identifying as queer, to experiences from his eclectic childhood on three continents? Darren was born in Ottawa before his family went on the move — first to Texas, then to France, then to Dakar, Senegal. There on the African continent, Darren sought out a local piano teacher who had studied with the venerable pedagogue Alfred Cortot. Thus Darren gained his entry into the authentic classical tradition: through his teachers in Dakar and eventually in Canada, he is the direct heir to the musical lineages of Chopin and Beethoven. But how does a disciple carry out their legacy for today’s audiences, whether in Africa or in North America? Here Darren counters with a question: “Why perpetuate classical music in the context of social disparity. What is its relevance?” That was the probing sentiment that instilled his spirit to search for answers — and self-made opportunities. -

Alliance for Canadian New Music Projects Presents

Alliance for Canadian New Music Projects presents Festival: November 23 - 25, 2018 Rooms 1-29, 2-28 & Studio 27, University of Alberta, Fine Arts Building Saturday, November 24, 2018 25th Anniversary Commission Classes, 6 - 8 pm Young Composers Program Final Concert, 8 pm Studio 27, University of Alberta, Fine Arts Building Gala Concert: Friday, November 30, 7:00 pm Muttart Hall, Alberta College, 10050 MacDonald Drive 3 4 ALLIANCE FOR CANADIAN Dear Contemporary Showcase Edmonton, NEW MUSIC PROJECTS Congratulations on your 25th Anniversary! This is a major milestone and you are celebrating it in a creative and memorable way. Edmonton has always been a vital Showcase centre, proudly and effectively promoting the teaching, performance and composition of Canadian Music. Throughout the years, we have marvelled at your expansion of musical activities including the establishment of your Young Composers Program and commissioning of works by Albertan composers. Performers from your centre have received many National Awards for their inspired performances which serves as a testament to the lasting impact of your presence. Thanks to the dedicated committee members, through this quarter century, contemporary Canadian music is thriving in Edmonton. We look forward to celebrating many more milestones with you in the years to come! Jill Kelman President ACNMP October 5, 2018 To: Edmonton Contemporary Showcase Congratulations on the 25th Anniversary of Edmonton Contemporary Showcase, a remarkable achievement in presenting this important mechanism for -

Burkholder/Grout/Palisca, Eighth Edition, Chapter 35 38 Chapter 35

38 17. After WW II, which group determined popular music styles? Chapter 35 Postwar Crosscurrents 18. (910) What is the meaning of generation gap? 1. (906) What is the central theme of Western music history since the mid-nineteenth century? 19. The music that people listened to affected their ____ and _______. 2. What are some of the things that pushed this trend? 20. What is the meaning of charts? 3. Know the definitions of the boldface terms. 21. What is another term for country music? What are its sources? 4. What catastrophic event occurred in the 1930s? 40s? 5. (907) Who are the existentialist writers? 22. (911) Why was it valued? 6. What political element took control of eastern Europe? 23. Describe the music. 7. What is the name of the political conflict? What are the names of the two units and who belongs to each? 24. What are the subclassifications? 8. What's the next group founded in 1945? 25. Name the stars. 9. What are the next wars? What is the date of the moon landing? 26. What's the capital? Theatre? 27. What's the new style that involves electric guitars? City? 10. TQ: What is a baby boom? G.I. Bill? Musician? 28. What phrase replaced "race music." 11. (908) Know the meaning of 78-rpm, LP, "45s." 12. Know transistor radio and disc jockey. 29. What comprised an R&B group? 13. When were tape recorders invented? Became common? 14. (909) When did India become independent? 30. What structure did they use? 15. Name the two figures important for the civil rights 31. -

Nadia Boulanger's Lasting Imprint on Canadian Music

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 06:24 Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Providing the Taste of Learning: Nadia Boulanger’s Lasting Imprint on Canadian Music Jean Boivin Musical Perspectives, People, and Places: Essays in Honour of Carl Résumé de l'article Morey Cet article retrace le riche héritage canadien de la grande personnalité de la Volume 33, numéro 2, 2013 musique française du XXe siècle qu’était Nadia Boulanger (1887–1979). À travers son enseignement auprès d’une soixantaine d’élèves canadiens, tant URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1032696ar francophones qu’anglophones, la célèbre pédagogue française a joué un rôle DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1032696ar important dans le développement de la musique de concert au Canada à partir des années 1920, en particulier à Montréal et à Toronto. Ses nombreux étudiants canadiens ont continué de se démarquer en tant que compositeurs, Aller au sommaire du numéro enseignants, artistes, musicologues, théoriciens, administrateurs, et producteurs de radio. En se basant sur une longue recherche dans les archives et les sources de première main, l’auteur démontre l’impact décisif qu’a eu Éditeur(s) Nadia Boulanger sur le développement de styles musicaux et de pratiques compositionnelles au Canada au cours du siècle dernier. Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 1911-0146 (imprimé) 1918-512X (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Boivin, J. (2013). Providing the Taste of Learning: Nadia Boulanger’s Lasting Imprint on Canadian Music. Intersections, 33(2), 71–100. https://doi.org/10.7202/1032696ar Copyright © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Reconsidering Pitch Centricity Stanley V

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 2011 Reconsidering Pitch Centricity Stanley V. Kleppinger University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Commons Kleppinger, Stanley V., "Reconsidering Pitch Centricity" (2011). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 63. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/63 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Reconsidering Pitch Centricity STANLEY V. KLEPPINGER Analysts commonly describe the musical focus upon a particular pitch class above all others as pitch centricity. But this seemingly simple concept is complicated by a range of factors. First, pitch centricity can be understood variously as a compositional feature, a perceptual effect arising from specific analytical or listening strategies, or some complex combination thereof. Second, the relation of pitch centricity to the theoretical construct of tonality (in any of its myriad conceptions) is often not consistently or robustly theorized. Finally, various musical contexts manifest or evoke pitch centricity in seemingly countless ways and to differing degrees. This essay examines a range of compositions by Ligeti, Carter, Copland, Bartok, and others to arrive at a more nuanced perspective of pitch centricity - one that takes fuller account of its perceptual foundations, recognizes its many forms and intensities, and addresses its significance to global tonal structure in a given composition. -

Filumena and the Canadian Identity a Research Into the Essence of Canadian Opera

Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final thesis for the Bmus-program Icelandic Academy of the Arts Music department May 2020 Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final Thesis for the Bmus-program Supervisor: Atli Ingólfsson Music Department May 2020 This thesis is a 6 ECTS final thesis for the B.Mus program. You may not copy this thesis in any way without consent from the author. Abstract In this thesis I sought to identify the essence of Canadian opera and to explore how the opera Filumena exemplifies that essence. My goal was to first establish what is unique about Canadian opera. To do this, I started by looking into the history of opera composition and performance in Canada. By tracing these two interlocking histories, I was able to gather a sense of the major bodies of work within the Canadian opera repertoire. I was, as well, able to deeper understand the evolution, and at some points, stagnation of Canadian opera by examining major contributing factors within this history. My next steps were to identify trends that arose within the history of opera composition in Canada. A closer look at many of the major works allowed me to see the similarities in terms of things such as subject matter. An important trend that I intend to explain further is the use of Canadian subject matter as the basis of the operas’ narratives. This telling of Canadian stories is one aspect unique to Canadian opera. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE CANADIAN MUSIC SINCE 1940: a QUESTION of NATIONALISM a Thesis Submitted in Partial Satis

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE CANADIAN MUSIC SINCE 1940: A QUESTION OF NATIONALISM A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music by Ronald Frederick Erin August, 1983 J:lhe Thesis of Ronald Frederick Erin is approved: California StD. te Universi tJr, Northridge ii PREFACE This thesis represents a survey of Canadian music since 1940 within the conceptual framework of 'nationalism'. By this selec- tive approach, it does not represent a conclusive view of Canadian music nor does this paper wish to ascribe national priorities more importance than is due. However, Canada has a unique relationship to the question of nationalism. All the arts, including music, have shared in the convolutions of national identity. The rela- tionship between music and nationalism takes on great significance in a country that has claimed cultural independence only in the last 40 years. Therefore, witnessed by Canadian critical res- ponse, the question of national identity in music has become an important factor. \ In utilizing a national focus, I have attempted to give a progressive, accumulative direction to the six chapters covered in this discussion. At the same time, I have attempted to make each chapter self-contained, in order to increase the paper's effective- ness as a reference tool. If the reader wishes to refer back to information on the CBC's CRI-SM record label or the Canadian League of Composers, this informati6n will be found in Chapter IV. Simi- larly, work employing Indian texts will be found in Chapter V. Therefore, a certain amount of redundancy is unavoidable when interconnecting various components. -

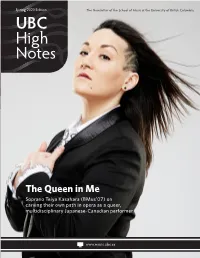

Spring 2020 Edition the Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia UBC High Notes

Spring 2020 Edition The Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia UBC High Notes The Queen in Me Soprano Teiya Kasahara (BMus’07) on carving their own path in opera as a queer, multidisciplinary Japanese-Canadian performer www.music.ubc.ca SPOTLIGHT LIBERATING THE QUEEN IN ME Photo: Takumi Hayashi/UBC In their new play The Queen in Me, soprano Teiya Kasahara (BMus’07) liberates one of opera’s most iconic villains — and challenges the industry’s centuries-old prejudices Photo: Tallulah By Tze Liew In The Queen in Me, the Queen of the Night at age 15, after seeing Ingmar Bergman’s film begins to sing her most iconic aria, “Der Hölle version of The Magic Flute. “I saw her perform For more than two centuries, the iconic Queen Rache,” like she would in any Magic Flute show. and was like, Oh God, I want to do that,” they of the Night from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte But midway through, she halts. “Stopp! Stopp remember. has been thrilling audiences with her vengeful die Musik!” she screams. Breaking the fourth spirit, bloodthirsty drive, and volatile high Fs. wall, she laments the stifling act everyone’s With this as their dream role, Kasahara dove Qualities that make her the ultimate villain, come to see; one she’s been trapped in for headfirst into voice training, made it into fated to eternal doom while the hero and over two centuries. the UBC Opera program, and honed their heroine, demure as lambs, skip off to enjoy craft for four years under the tutelage of their happy ending. -

The Piano Music of Jean Coulthard: an Historical Perspective

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiU indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 The Piano Music of Jean Couithard By Glenn David Colton B.Mus., Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1990 M.A. (Music Criticism), McMaster University, 1992 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Musicology) in the Department of Music We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard fl$r. -

October 8, 1982 Concert Program

NEW MUSIC CONCERTS 1982-83 CONTEMPORARY ENCOUNTERS. CANADIAN MUSIC. GOOD MUSIC. On Sale now from the Canadian Music Centre are: CMC 1 Canadian Electronic Ensemble. Music composed and performed by Grimes, Jaeger, Lake and Montgomery. CMC 0281 Spectra - The Elmer Iseler Singers. Choral music by Ford, Morawetz and Somers. CMC 0382 Sonics - Antonin Kubalek. Piano solo music by Anhalt, Buczynski and Dolin. CMC 0682 Washington Square - The London Symphony Orchestra. Ballet music by Michael Conway Baker. CMC 0582 ‘Private Collection - Philip Candelaria, Mary Lou Fallis, Monica Gaylord. The music of John Weinzweig. CMC 0482 Folia - Available October 1, 1982. Wind quintet music by Cherney, Hambraeus, Sherman and Aitken, performed by the York Winds. In production: Orders accepted now: CMC 0782 2x4- The Purcell String Quartet. Music by Pentland and Somers. CMC 0883 Viola Nouveau - Rivka Golani-Erdesz. Music by Barnes, Joachim, Prévost, Jaeger and Cherney. Write or phone to place orders, or for further information contact: The Canadian Music Centre 1263 Bay Street Toronto, Ontario MSR 2C!1 (416) 961-6601 NEW MUSIC CONCERTS Robert Aitken Artistic Director presents COMPOSERS: HARRY FREEDMAN LUKAS FOSS ALEXINA LOUIE BARBARA PENTLAND GUEST SOLOISTS: ERICA GOODMAN BEVERLEY JOHNSTON MARY MORRISON JOSEPH MACEROLLO October 8, 1982 8:30 P.M. Walter Hall, Edward Johnson Building, University of Toronto EER IONG..R AM REFUGE (1981) ALEXINA LOUIE JOSEPH MACEROLLO, accordion ERICA GOODMAN, harp BEVERLEY JOHNSTON, vibraphone COMMENTA (1981) BARBARA PENTLAND ERICA