Investi^Gitions Recorded in His Mode of Work and in His General Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

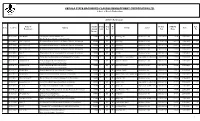

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Athirapally Hydel Electric Project

Athirapally Hydel Electric Project drishtiias.com/printpdf/athirapally-hydel-electric-project Why in News Recently, the Kerala government has approved the proposed Athirapally Hydro Electric Project (AHEP) on the Chalakudy river in Thrissur district of the state. There are already five dams for power and one for irrigation and it will be the seventh along the 145 km course of the Chalakudy river. Chalakudy River It originates in the Anamalai region of Tamil Nadu and is joined by its major tributaries Parambikulam, Kuriyarkutti, Sholayar, Karapara and Anakayam in Kerala. The river flows through Palakkad, Thrissur and Ernakulam districts of Kerala. It is the 4th longest river in Kerala and one of very few rivers of Kerala, which is having relics of riparian vegetation in substantial level. A riparian zone is the interface between land and a river or stream. Plant habitats and communities along the river margins and banks are called riparian vegetation, characterized by hydrophilic plants. It is the richest river in fish diversity perhaps in India as it contains 85 species of freshwater fishes out of the 152 species known from Kerala only. The famous waterfalls, Athirappilly Falls and Vazhachal Falls, are situated on this river. It merges with the Periyar River near Puthenvelikkara in Ernakulam district. Key Points 1/3 The total installed capacity of AHEP is 163 MW and the project is supposed to make use of the tail end water coming out of the existing Poringalkuthu Hydro Electric Project that is constructed across the Chalakudy river. AHEP envisages diverting water from the Poringalkuthu project as well as from its own catchment of 26 sq km. -

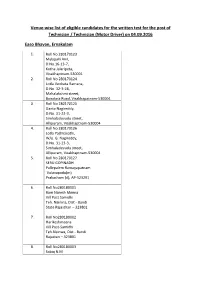

(Motor Driver) on 04.09.2016

Venue-wise list of eligible candidates for the written test for the post of Technician / Technician (Motor Driver) on 04.09.2016 Easo Bhavan, Ernakulam 1. Roll No 280170123 Mylapalli Anil, D.No.16-13-7, Kotha Jalaripeta, Visakhaptnam-530001 2. Roll No 280170124 Lotla Venkata Ramana, D.No. 32-3-28, Mahalakshmi street, Bowdara Road, Visakhapatnam-530004 3. Roll No 280170125 Ganta Nagireddy, D.No. 31-23-3, Simhaladevudu street, Allipuram, Visakhaptnam-530004 4. Roll No 280170126 Lotla Padmavathi, W/o. G. Nagireddy, D.No. 31-23-3, Simhaladevudu street, Allipuram, Visakhaptnam-530004 5. Roll No 280170127 SERU GOPINADH Pallepalem Ramayapatnam Vulavapadu(m) Prakasham (d), AP-523291 6. Roll No280180001 Ram Naresh Meena Vill Post Samidhi Teh. Nainina, Dist - Bundi State Rajasthan – 323801 7. Roll No280180002 Harikeshmeena Vill Post-Samidhi Teh.Nainwa, Dist - Bundi Rajastan – 323801 8. Roll No280180003 Sabiq N.M Noor Mahal Kavaratti, Lakshadweep 682555 9. Roll No280180004 K Pau Biak Lun Zenhanglamka, Old Bazar Lt. Street, CCPur, P.O. P.S. Manipur State -795128 10. Roll No280180005 Athira T.G. Thevarkuzhiyil (H) Pazhayarikandom P.O. Idukki – 685606 11. Roll No280180006 P Sree Ram Naik S/o P. Govinda Naik Pedapally (V)Puttapathy Anantapur- 517325 12. Roll No280180007 Amulya Toppo Kokkar Tunki Toli P.O. Bariatu Dist - Ranchi Jharkhand – 834009 13. Roll No280180008 Prakash Kumar A-1/321 Madhu Vihar Uttam Nagar Newdelhi – 110059 14. Roll No280180009 Rajesh Kumar Meena VPO Barwa Tehsil Bassi Dist Jaipur Rajasthan – 303305 15. Roll No280180010 G Jayaraj Kumar Shivalayam Nivas Mannipady Top P.O. Ramdas Nagar Kasargod 671124 16. Roll No280180011 Naseefahsan B Beathudeen (H) Agatti Island Lakshasweep 17. -

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 14 Points of Jinnah (March 9, 1929) Phase “II” of CDM

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 1 www.teachersadda.com | www.sscadda.com | www.careerpower.in | Adda247 App General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Contents General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................ 3 Indian Polity for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 3 Indian Economy for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ........................................................................................... 22 Geography for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 23 Ancient History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 41 Medieval History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .......................................................................................... 48 Modern History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 58 Physics for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .........................................................................................................73 Chemistry for AFCAT II 2021 Exam.................................................................................................... 91 Biology for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ....................................................................................................... 98 Static GK for IAF AFCAT II 2021 ...................................................................................................... -

Ac Name Ac Addr1 Ac Addr2 Ac Addr3 K C Joy Kallely

AC_NAME AC_ADDR1 AC_ADDR2 AC_ADDR3 K C JOY KALLELY HOUSE NEAR WEST CHURCH ANGAMALY.P.O SAMUEL K I ANDOOR HOUSE P O BOX 621 U C COLLEGE P.O, ALWAYE 683102 ARUN PAUL AMBOOKEN HOUSE ANAPPARA ANNALLOOR P O THRESSIAMMA THOMAS PUTHENVEETIL HOUSE PALAYAMPARAMBU MADHAVAN NAIR P ROOM NO.74,SAIBABA NAGAR, SHELL COLONY ROAD,CHEMBUR, MUMBAI-71. SAGIR KHAN C/O.ACHELAL S.JAYSWAL K-7,1/3.SHIVNERI NAGAR W.T.PATIL MARG.,N.R.ACHARYA OUSEPH C D MALIAKKAL CHETTAKA HOUSE CHALAKUDY TCR DT ASHARAF P H PARUVINGAL HOUSE KUNNATHERY CHALISSERY P O SUSAMMA . KOSHY PRINCE BHAVAN MANAPUZA PO KOLLAM DIST THOMASKUTTY KOCHUKOSHY SUBHA COTTAGE PUTHOOR PO SAHADEVAN K PEDARAPLAVU, THAMARAKKULAM, CHARUMOODU.P.O. ST JOSEPHS CHURCH PARISH PRIEST KAIKARAN BISHOP OF KOLLAM ARUMUGHAN K.P S/O PERUMAL PILLAI SALAIPUDUR GOPAL R S/O RAMASAMY CONTRACTOR SOLAKALIPALAYAM SELVARAJ S/OPALANISAMY 58,VELAYUDANPALAYAM EZHUNOOTHIMANGALAM CHANDRAMATHY VELAYUDHAN KAITHOLIL EZHACHERRY USHA BINNY KALISSERIL HOUSE CHINGAVANAM PO KOTTAYAM PARUKUTTY AMMA T M W/O KARUNAKARA PANIKKAR THEKKEMARIYIL HOUSE PRUTHIPULLY SANTHOSH K S . KAVATHIKODE HOUSE KOTTAYI P O PALAKKAD KUNHALAVI K S/O AHAMMED KUTTY KUTTIPPALA VIA EDARIKODE 676501 MALAPPURAM DISTRICT ITTIYARA K P BLESS BHAVAN KANIPAYOOR PRADEEP P V S/O VASU THEKKEPURAKKAL HOUSE P.O.PERAKAM,POOKODE,THRISSUR MURALEEDHARAN K B S/O BALAN PANICKER KOOTTALA KALARICKAL P O ARIMBUR MUHAMMEDISHAK V P S/O MUHAMMEDKUTTY VAITHALAPARAMBAN HOUSE KAMBALAKAD P O KALPETTA VIA SIDHIQ C S/O ENU CHENATH HOUSE MARANCHRY MANOHARAN K S KATTIKULAM HOUSE PORATHUSSERY HOUSE IRINJALAKUDA PRABHATH P NAIR SREEVILASAM CHITTADY P O GRACE ANDREWS OLAKKENGIL HOUSE, P.O.PAVARATTY. -

Geochemical Modeling of Groundwater in Chinnar River Basin: a Source Identification Perspective

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Aquatic Procedia 4 ( 2015 ) 986 – 992 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON WATER RESOURCES, COASTAL AND OCEAN ENGINEERING (ICWRCOE 2015) Geochemical Modeling of Groundwater in Chinnar River Basin: A Source Identification Perspective Suma CS*, Srinivasamoorthy K, Saravanan K, Faizalkhan A, Prakash R, Gopinath S Pondicherry University, Department of Earth sciences, Pondicherry, India -605014 Abstract Understanding the geochemical evolution of groundwater is an essential part of the performance assessment and safety analysis of the geological system. Geochemical modeling techniques using PHREEQCI will aid in demarcating the main factors and mechanisms controlling the chemistry of groundwater. An attempt has been made in hard rock terrain of Chinnar basin, Dharmapuri district of Tamilnadu, India to interpret the processes and factors controlling hydrogeochemistry of groundwater. The area is made up of rock units belonging to Charnockite and Granitic Gneiss. Groundwater chemistry has been attempted + + 2+ 2+ - - - - based on laboratory observations of major cations like Na , K , Ca and Mg and anions like Cl , HCO3 , NO3 , F , 2- 3- SO4 and PO4 . Piper diagram reveals higher bicarbonate, calcium and magnesium along the recharge zones and tend to decrease along the flow path and vice versa for ions like sodium, potassium and chloride. Two flow paths based on piper and saturation index were identified for two major lithounits. The granitic terrain shows precipitation of calcium and sulfate minerals and dissolution of silicate minerals. The charnockite terrain shows precipitation of silicates and dissolution of calcium and sulfate minerals. From initial to final solution slight variation in calcium and sulfate stability were identified but drastic change with reference to silicate minerals stability due to effective dissolution of silicate minerals from the litho units of the study area. -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology. -

UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Country: India

1 UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Country: India PROJECT DOCUMENT Project Title: India High Range Landscape Project - Developing an effective multiple-use management framework for conserving biodiversity in the mountain landscape of the High Ranges, the Western Ghats, India. UNDAF Outcome(s)/ Indicator(s): Inclusive and equitable growth policies and poverty reduction strategies of the Government are strengthened to ensure that most vulnerable and marginalized people in rural and urban areas have greater access to productive assets, decent employment, skill development, social protection and sustainable livelihoods. UNDP Strategic Plan Primary Outcome: Mainstreaming biodiversity conservation and sustainable use into production landscapes. Expected CPAP Outcome(s) /Output/Indicator(s): Sustainable management of biodiversity and land resource is enhanced. Executing Entity/ Implementing Partner: UNDP India Country Office Implementing Entity/ Responsible Partner: Department of Forests and Wildlife, Government of Kerala Brief description: The project will put in place a cross-sectoral land use management framework, and compliance monitoring and enforcement system to ensure that development in production sectors such as tea, cardamom and tourism is congruent with biodiversity conservation needs – to achieve the long term goal of conserving globally significant biological diversity in the High Ranges of the Western Ghats. It will seek to establish a conservation compatible mosaic of land uses, anchored in a cluster of protected areas, by -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kollam City District from 21.06.2020To27.06.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kollam City district from 21.06.2020to27.06.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Address of Cr. No & Sec Police father of which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex Accused of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr.2120/2020 U/S 269, 188, SHEMEERA 270 IPC & MANZIL, 4(2)(a) r/w 5 MUHAMMED Male, 1 SABU PEOPELES NAGAR Kadappakkada 21.06.2020 of Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail HANEEFA Age:37 337, Epidemic KADAPPAKKADA Disease Ordinance 2020 Cr.2121/2020 U/S 269, 188, ANUGRAHA 270 IPC & NAGAR 190, 4(2)(a) r/w 5 Male, 2 JOSE VARGEESE PALLITHOTTAM, Kadappakkada 21.06.2020 of Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail Age:27 KOLLAM EAST Epidemic Police Station Disease Ordinance 2020 Cr.2122/2020 U/S 269, 188, 270 IPC & BHDRADEEPAM, 4(2)(a) r/w 5 Male, 3 GLEN MARY DALE, Kadappakkada 21.06.2020 of Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail CHRISTPHER Age:32 NrVANCHKOVIL Epidemic Disease Ordinance 2020 Cr.2123/2020 U/S 269, 188, PEROOR 270 IPC & VADAKKATHIL, 4(2)(a) r/w 5 Male, 4 SHEFEEK SHARAFUDE VALANTHUNGAL, Pulimoodu 21.06.2020 of Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail Age:31 EN ERAVIPURAM Epidemic Police Station Disease Ordinance 2020 Cr.2125/2020 U/S 269, 188, PUTHUVAL 270 IPC & PURAYIDOM, 4(2)(a) r/w 5 Male, 5 NISHAD RAJU BEECH NAGAR58 Mundakkal 21.06.2020 of Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail Age:20 MUNDAKKAL, Epidemic KOLLAM Disease Ordinance -

Distribution of Mammals and Birds in Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary

KFRI Research Report 131 DISTRIBUTION OF MAMMALS AND BIRDS IN CHINNAR WILDLIFE SANCTUARY P. Vijayakumaran Nair K.K. Ramachandran E.A. Jayson KERALA FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE PEECHI, THRISSUR December 1997 Pages: 31 CONTENTS Page File Abstract r.131.2 1 Introduction 1 r.131.3 2 Methods 4 r.131.4 3 Results and Discussion 7 r.131.5 4 References 24 r.131.6 5 Appendices 27 r.131.7 ABSTRACT A study was conducted during 1990-1992 in Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary ( 10" 15' to 10" 22' N latitude and 77" 05' to 77" 17' E longitude) of Kerala State to gather information on the distribution of mammals and birds in the area. The study revealed the occurrence of 17 larger mammals. A total of 59 elephants were recorded from the area. Age-sex composition of the herds were similar to that in other populations. Forty three individuals of sambar were sighted, the herd size and composition is comparable with that of other places. This pattern was applicable to the spotted deer also. Other animals include the wild pig, gaur, bonnet macaque, hanuman langur, leopard, wilddog. etc. Hundred and forty three species of birds from thirty four families were recorded from the study area. The birds found in the study area is compared with distribution in other wild life sanctuaries in Kerala. Few birds are peculiar to the Chinnar area, few birds common in other parts of Kerala are rare in the area. The riverine forests in the area is important for the survival of the endangered grizzled giant squirrel, Ratuf'a macroura.