Brander.Dissertation.July 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Azharos-Piyuttim Unique to Shavuos

dltzd z` oiadl Vol. 10 No. 17 Supplement b"ryz zereay zexdf`-miheit Unique To zereay The form of heit known as dxdf` is recited only on the holiday of 1zereay. An dxdf` literary means: a warning. As a form of heit, an dxdf` represents a poem in which the author weaves into the lines of the poem references to each of the zeevn b"ixz. Why did this form of heit become associated with the holiday of zereay? Is there a link between the zexdf` and the zexacd zxyr? To answer that question, we need to ask some additional questions. Should we be reciting the zexacd zxyr as part of our zelitz each day and why do we not? In truth, we should be reciting the zexacd zxyr as part of our zelitz. Such a recital would represent an affirmation that the dxez was given at ipiq xd and that G-d’s revelation occurred at that time. We already include one other affirmation in our zelitz; i.e. z`ixw rny. The devn of rny z`ixw is performed each day for two reasons; first, because the words in rny z`ixw include a command to recite these words twice each day, jakya jnewae, and second, because the first verse of rny z`ixw contains an affirmation; that G-d is the G-d of Israel and G-d is the one and only G-d. The recital of that line constitutes the Jewish Pledge of Allegiance. Because of that, some mixeciq include an instruction to recite the first weqt of rny z`ixw out loud. -

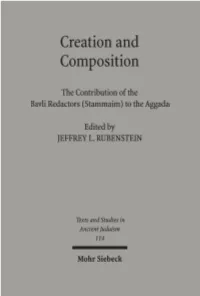

Creation and Composition

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Martin Hengel und Peter Schäfer 114 ARTIBUS ,5*2 Creation and Composition The Contribution of the Bavli Redactors (Stammaim) to the Aggada Edited by Jeffrey L. Rubenstein Mohr Siebeck Jeffrey L. Rubenstein, born 1964. 1985 B.A. at Oberlin College (OH); 1987 M.A. at The Jewish Theological Seminary of America (NY); 1992 Ph.D. at Columbia University (NY). Professor in the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, New York University. ISBN 3-16-148692-7 ISSN 0721-8753 (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2005 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen, printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Preface The papers collected in this volume were presented at a conference sponsored by the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies of New York University, February 9-10, 2003.1 am grateful to Lawrence Schiffman, chairman of the de- partment, for his support, and to Shayne Figueroa and Diane Leon-Ferdico, the departmental administrators, for all their efforts in logistics and organization. -

SHEMA YISRAEL II After the First Pasuk, We Recite “Baruch Shem Kevod Malchuso Leolam Vaed - Blessed Is the Name of His Glorious Kingdom for All Eternity

*Please respond describing if and how these Tefillah Tips are disseminated to members. Thank you* SHEMA YISRAEL II After the first pasuk, we recite “Baruch Shem Kevod Malchuso Leolam Vaed - Blessed is the Name of His glorious kingdom for all eternity. The simple understanding as to why we don’t say Baruch Shem out loud is because unlike the rest of the Shema, Baruch Shem is nowhere to be found in the written Torah and interrupts two Biblical sentences. It is however mentioned in the Talmud in tractate Pesachim 56A that our Father, Jacob said this sentence to his children before passing away (see last week’s edition). Therefore the Talmud concludes it should be said in an undertone. The Shema continues with the words “Veahavta Et Hashem Elokecha - And you shall love the Lord your G-d”. How exactly are you to express your love unto Him? “Bechol Levavecha, uvechol nafshecha, uvechol meodecha - with all of your heart, your soul, and your possessions”. The commentators ask, “How can the Torah command us to emote”?! We are commanded to don Tefillin, to eat kosher, and to observe the Shabbat, but to love G-d? Emotions are triggered and experienced but are not necessarily accessible at will. How then shall we understand - “Veahavta Et Hashem - You Shall love G-d”? HaRav Baruch HaLevi Epstein zt”l (1860-1941) in his work on the Siddur, The Baruch Sheamar advances two approaches to understanding this verse. The first approach maintains the literal translation of Veahavta – You shall love Him. He explains that the commandment of “Veahavta” must be seen in light of the previous prayer in the Siddur - “Ahava Rabbah”. -

Lincoln Square Synagogue for As Sexuality, the Role Of

IflN mm Lincoln Square Synagogue Volume 27, No. 3 WINTER ISSUE Shevat 5752 - January, 1992 FROM THE RABBI'S DESK.- It has been two years since I last saw leaves summon their last colorful challenge to their impending fall. Although there are many things to wonder at in this city, most ofthem are works ofhuman beings. Only tourists wonder at the human works, and being a New Yorker, I cannot act as a tourist. It was good to have some thing from G-d to wonder at, even though it was only leaves. Wondering is an inspiring sensation. A sense of wonder insures that our rela¬ tionship with G-d is not static. It keeps us in an active relationship, and protects us from davening or fulfilling any other mitzvah merely by rote. A lack of excitement, of curiosity, of surprise, of wonder severs our attachment to what we do. Worse: it arouses G-d's disappointment I wonder most at our propensity to cease wondering. None of us would consciously decide to deprive our prayers and actions of meaning. Yet, most of us are not much bothered by our lack of attachment to our tefilot and mitzvot. We are too comfortable, too certain that we are living properly. That is why I am happy that we hosted the Wednesday Night Lecture with Rabbi Riskin and Dr. Ruth. The lecture and the controversy surrounding it certainly woke us up. We should not need or even use controversy to wake ourselves up. However, those of us who were joined in argument over the lecture were forced to confront some of the serious divisions in the Orthodox community, and many of its other problems. -

Salvation and Redemption in the Judaic Tradition

Salvation and Redemption in the Judaic Tradition David Rosen In presenting Judaic perspectives on salvation and redemption, distinction must be made between the national dimensions on the one hand and the personal on the other, even though the latter is of course seen as related to the national whole, for better or worse (see TB Kiddushin 40b). Individual Salvation Biblical Teachings Redemption and salvation imply the need for deliverance from a particular situation, condition, or debt. The Hebrew word for redemption, gəʾullāh, implies “the prior existence of obligation.” This word is used in Leviticus to describe the nancial redemption of ancestral land from another to whom it has been sold (see Leviticus 25:25); the nancial redemption of a member of one family bound in servitude to another family because of debt (see Leviticus 25:48–49); and the redemption of a home, eld, ritually impure animal, or agricultural tithe that had been dedicated to the sanctuary by giving its nancial value plus one-fth in lieu thereof (see Leviticus 27). In the case of a male who died childless, his brothers assumed an obligation to “redeem” the name of the deceased —that is, to save it from extinction by ensuring the continuity of his seed, lands, and lial tribute (see Deuteronomy 25:5–10; Ruth 4:1–10). In a case of murder, the gôʾēl was the blood avenger who sought to requite the wrong by seeking blood for blood, redeeming thereby, if not the “wandering soul” of the deceased, certainly the honor that had been desecrated (see Numbers 35:12–29; cf. -

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract Julius Theodor (1849–1923)

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract This article is a biography of the prominent scholar of Aggadic literature, Rabbi Dr Julius Theodor (1849–1923). It describes Theodor’s childhood and family and his formative years spent studying at the Breslau Rabbinical Seminary. It explores the thirty one years he served as a rabbi in the town of Bojanowo, and his final years in Berlin. The article highlights The- odor’s research and includes a list of his publications. Specifically, it focuses on his monumental, pioneering work preparing a critical edition of Bereshit Rabbah (completed by Chanoch Albeck), a project which has left a deep imprint on Aggadic research to this day. Der folgende Artikel beinhaltet eine Biographie des bedeutenden Erforschers der aggadischen Literatur Rabbiner Dr. Julius Theodor (1849–1923). Er beschreibt Theodors Kindheit und Familie und die ihn prägenden Jahre des Studiums am Breslauer Rabbinerseminar. Er schil- dert die einunddreissig Jahre, die er als Rabbiner in der Stadt Bojanowo wirkte, und seine letzten Jahre in Berlin. Besonders eingegangen wird auf Theodors Forschungsleistung, die nicht zuletzt an der angefügten Liste seiner Veröffentlichungen ablesbar ist. Im Mittelpunkt steht dabei seine präzedenzlose monumentale kritische Edition des Midrasch Bereshit Rabbah (die Chanoch Albeck weitergeführt und abgeschlossen hat), ein Werk, das in der Erforschung aggadischer Literatur bis heute nachwirkende Spuren hinterlassen hat. Julius Theodor (1849–1923) is one of the leading experts of the Aggadic literature. His major work, a scholarly edition of the Midrash Bereshit Rabbah (BerR), completed by Chanoch Albeck (1890–1972), is a milestone and foundation of Jewish studies research. His important articles deal with key topics still relevant to Midrashic research even today. -

Wertheimer, Editor Imagining the Seth Farber an American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B

Imagining the American Jewish Community Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor For a complete list of books in the series, visit www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSAJ.html Jack Wertheimer, editor Imagining the Seth Farber An American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B. Murray Zimiles Gilded Lions and Soloveitchik and Boston’s Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to Maimonides School the Carousel Ava F. Kahn and Marc Dollinger, Marianne R. Sanua Be of Good editors California Jews Courage: The American Jewish Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe “How Committee, 1945–2006 Goodly Are Thy Tents”: Summer Hollace Ava Weiner and Kenneth D. Camps as Jewish Socializing Roseman, editors Lone Stars of Experiences David: The Jews of Texas Ori Z. Soltes Fixing the World: Jewish Jack Wertheimer, editor Family American Painters in the Twentieth Matters: Jewish Education in an Century Age of Choice Gary P. Zola, editor The Dynamics of American Jewish History: Jacob Edward S. Shapiro Crown Heights: Rader Marcus’s Essays on American Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Jewry Riot David Zurawik The Jews of Prime Time Kirsten Fermaglich American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares: Ranen Omer-Sherman, 2002 Diaspora Early Holocaust Consciousness and and Zionism in Jewish American Liberal America, 1957–1965 Literature: Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth Andrea Greenbaum, editor Jews of Ilana Abramovitch and Seán Galvin, South Florida editors, 2001 Jews of Brooklyn Sylvia Barack Fishman Double or Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed editors Women and American Marriage Judaism: Historical Perspectives George M. -

Community Celebrates Together Reflections on a Famous Grandfather – Marc Chagall Japan and Israel Establish Closer Ties

UJF 2014 Honor Roll Non-profit Organization U.S. POSTAGE PAID United Jewish Federation of Greater Permit # 184 Stamford, New Canaan and Darien Watertown, NY is pleased to publish its 2014 Honor Roll to publicly thank the individuals, families, foundations and businesses who have made gifts to the 2014 Bet- ter Together Annual Community Campaign and Special Programs to help fund the important Jewish causes supported by UJF. Please turn to insert. march 2015/Adar-nisan 5775 a publication of United jewish federation of Volume 17, Number 2 Greater Stamford, New Canaan and Darien Reflections on a Famous Community Celebrates Grandfather – Marc Chagall Together By Elissa Kaplan chair, who was a collector of Art historian, costume and art, especially Jewish folk art. Shabbat Across Stamford mask creator, and floral de- Temple Sinai is a co-sponsor By Marcia Lane “Words That Hurt, Words That Heal: signer Bella Meyer will speak of the program. “On March 13, the Stamford Jewish Choosing Words Wisely.” He is the about her grandfather, Marc Throughout her life, Mey- community will do something ordinary author of novels and screenplays, and Chagall, as part of the Jewish er has been immersed in the and something extraordinary,” said UJF is widely acknowledged to be one of Historical Society of Fairfield world of art and has always Executive Director James Cohen. “We our greatest (and most entertaining) County’s March Featured painted. She was born in Paris will gather to celebrate Shabbat, as Jews Jewish speakers and teachers. His pre- Program. Meyer recalls her and raised in Switzerland. She do every Friday evening in every place sentation will be followed by a dessert earliest memory of her grand- left Switzerland the day she around the globe. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

Chief Rabbi Joseph Herman Hertz

A Bridge across the Tigris: Chief Rabbi Joseph Herman Hertz Our Rabbis tell us that on the death of Abaye the bridge across the Tigris collapsed. A bridge serves to unite opposite shores; and so Abaye had united the opposing groups and conflicting parties of his time. Likewise Dr. Hertz’s personality was the bridge which served to unite different communities and bodies in this country and the Dominions into one common Jewish loyalty. —Dayan Yechezkel Abramsky: Eulogy for Chief Rabbi Hertz.[1] I At his death in 1946, Joseph Herman Hertz was the most celebrated rabbi in the world. He had been Chief Rabbi of the British Empire for 33 years, author or editor of several successful books, and champion of Jewish causes national and international. Even today, his edition of the Pentateuch, known as the Hertz Chumash, can be found in most centrist Orthodox synagogues, though it is often now outnumbered by other editions. His remarkable career grew out of three factors: a unique personality and capabilities; a particular background and education; and extraordinary times. Hertz was no superman; he had plenty of flaws and failings, but he made a massive contribution to Judaism and the Jewish People. Above all, Dayan Abramsky was right. Hertz was a bridge, who showed that a combination of old and new, tradition and modernity, Torah and worldly wisdom could generate a vibrant, authentic and enduring Judaism. Hertz was born in Rubrin, in what is now Slovakia on September 25, 1872.[2] His father, Simon, had studied with Rabbi Esriel Hisldesheimer at his seminary at Eisenstadt and was a teacher and grammarian as well as a plum farmer. -

SEASONS CORPORATE LLC, Et Al., Debtors.1

Case 1-18-45284-nhl Doc 471 Filed 12/21/20 Entered 12/21/20 15:06:15 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re: Chapter 11 SEASONS CORPORATE LLC, et al., Case No. 18-45284 (nhl) Debtors.1 Jointly Administered ORDER CONFIRMING DEBTORS’ AND COMMITTEE’S JOINT PLAN OF LIQUIDATION The Debtors and the Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors (the “Committee”) having filed a Joint Plan of Liquidation, dated August 17, 2020 (ECF #417), together with an accompanying Disclosure Statement of even date (ECF #418); and the Debtors and the Committee having thereafter filed an Amended Joint Plan of Liquidation, dated October 30, 2020 (the “Plan”) (ECF #438), together with an accompanying Amended Disclosure Statement of even date (the “Disclosure Statement”) (ECF #437); and the Bankruptcy Court having entered an Order (ECF #440), approving the Disclosure Statement and scheduling a telephonic hearing to consider confirmation of the Plan on December 8, 2020 (the “Confirmation Hearing”); and the Plan and Disclosure Statement having been transmitted to all creditors and other parties-in- interest as evidenced by the affidavit of service on file with the Court (ECF #446); and no objections to confirmation of the Plan having been filed; and the Confirmation Hearing having been held on December 8, 2020, at which appeared Nathan Schwed (Counsel to Debtors), Kevin Nash (Counsel to Creditors Committee), Rachel Wolf (U.S. Trustee), Joel Getzler (Debtors’ 1 The Debtors in these Chapter 11 cases, together with the last four digits of their federal tax identification numbers, are as follows: Blue Gold Equities LLC (7766), Central Avenue Market LLC (7961), Am sterdam Avenue Market LLC (7988), Wilmot Road Market LLC (8020), Seasons Express Inwood LLC (1703), Sea sons Lakewood LLC (0295), Seasons Maryland LLC (1895), Seasons Clifton LLC (3331), Seasons Cleveland LLC (7367), Lawrence Supermarket LLC (8258), Upper West Side Supermarket LLC (8895), Seasons Property Management LLC (2672) and Seasons Corporate LLC (2266) (collectively the “Debtors”). -

Presenter Profiles

PRESENTER PROFILES RABBI KENNETH BRANDER Rabbi Kenneth Brander is Vice President for University and Community Life at Yeshiva University. He served as the inaugural David Mitzner Dean of Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future. Prior to his work at Yeshiva University, Rabbi Brander served for 14 years as the Senior Rabbi of the Boca Raton Synagogue. He oversaw its explosive growth from 60 families to over 600 families. While Senior Rabbi of the Boca Raton Synagogue (BRS), he became the founding dean of The Weinbaum Yeshiva High School, founding dean of the Boca Raton Judaic Fellows Program – Community Kollel and founder and posek of the Boca Raton Community Mikvah. He helped to develop the Hahn Judaic Campus on which all these institutions reside and as co-chair of Kashrut organization of the Orthodox Rabbinical Board of Broward & Palm Beach Counties (ORB). Rabbi Brander also served for five years as a Member of the Executive Board of the South Palm Beach County Jewish Federation, as a Board member of Jewish Family Services of South Palm Beach County, and actively worked with other lay leaders in the development of the Hillel Day School. Rabbi Brander is a 1984 alumnus of Yeshiva College and received his ordination from the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1986. During that time he served as a student assistant to the esteemed Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik. He also received an additional ordination from Rav Menachem Burstein the founder and dean of Machon Puah and from the Chief Rabbi, Mordechai Eliyahu, in the field of Jewish Law and Bioethics with a focus on reproductive technology, He is currently a PhD candidate (ABD) in general philosophy at Florida Atlantic University (FAU).