76978607.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stoke on Trent Pharmacies NHS Code Pharmacy Name Address Post Code Tel

Stoke On Trent Pharmacies NHS code Pharmacy Name Address Post Code Tel. No FRF34 Angelway Chemist 283 Waterloo Road Cobridge ST6 3HL 01782 280037 FJ346 ASDA Pharmacy Scotia Road Tunstall ST6 6AT 01782 820010 FKX58 Birchill & Watson 20 Knypersley Road Norton in the Moors ST6 8HX 01782 534678 FQK77 Blurton Pharmacy 7 Ingestre Square Blurton ST3 3JT 01782 314408 FRQ52 Boots the Chemists 39 Trentham Rd Longton ST3 4DF 01782 319758 FKV79 Boots the Chemists Unit 10 Alexandra Retail Park Scotia Road, Tunstall ST6 6BE 01782 838341 FDF31 Boots the Chemists 25 Bennett Precinct Longton ST3 2HX 01782 313819 FDH31 Boots the Chemists 3/5 Upper Market Square Hanley ST1 1PZ 01782 213271 FFV80 Boots the Chemists 41 Queen Street Burslem ST6 3EH 01782 837576 FK255 Boots the Chemists Bentilee Neighbourhood Centre Dawlish Drive, Bentilee ST2 0EU 01782 212667 FL883 Boots the Chemists Unit 5 Festival Park Hanley ST1 5SJ 01782 284125 Burslem Pharmacy Lucie Wedgwood Health Centre Chapel Lane, Burslem ST6 2AB 01782 814197 FWL56 Eaton Park Pharmacy 2 Southall Way Eaton Park ST2 9LT 01782 215599 FDF74 Grahams Pharmacy 99 Ford Green Road Smallthorne ST6 1NT 01782 834094 FTV00 Hartshill Pharmacy Hartshill Primary Care Centre Ashwell Road, Hartshill ST4 6AT 01782 616601 FRQ98 Heron Cross Pharmacy 2-4 Duke Street Heron Cross ST4 3BL 01782 319204 FFP79 Lloyds Pharmacy Cobridge Community H/ Centre Elder Road, Cobridge ST6 2JN 01782 212673 FM588 Lloyds Pharmacy 128 Werrington Road Bucknall ST2 9AJ 01782 219830 FA530 Lloyds Pharmacy Fenton Health Centre Glebedale Road, Fenton -

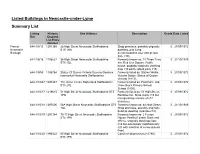

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-Under-Lyme Summary List

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-under-Lyme Summary List Listing Historic Site Address Description Grade Date Listed Ref. England List Entry Number Former 644-1/8/15 1291369 28 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Shop premises, possibly originally II 27/09/1972 Newcastle ST5 1RA dwelling, with living Borough accommodation over and at rear (late c18). 644-1/8/16 1196521 36 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 14 Three Tuns II 21/10/1949 ST5 1QL Inn, Red Lion Square. Public house, probably originally dwelling (late c16 partly rebuilt early c19). 644-1/9/55 1196764 Statue Of Queen Victoria Queens Gardens Formerly listed as: Station Walks, II 27/09/1972 Ironmarket Newcastle Staffordshire Victoria Statue. Statue of Queen Victoria (1913). 644-1/10/47 1297487 The Orme Centre Higherland Staffordshire Formerly listed as: Pool Dam, Old II 27/09/1972 ST5 2TE Orme Boy's Primary School. School (1850). 644-1/10/17 1219615 51 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly listed as: 51 High Street, II 27/09/1972 1PN Rainbow Inn. Shop (early c19 but incorporating remains of c17 structure). 644-1/10/18 1297606 56A High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly known as: 44 High Street. II 21/10/1949 1QL Shop premises, possibly originally build as dwelling (mid-late c18). 644-1/10/19 1291384 75-77 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 2 Fenton II 27/09/1972 ST5 1PN House, Penkhull street. Bank and offices, originally dwellings (late c18 but extensively modified early c20 with insertion of a new ground floor). 644-1/10/20 1196522 85 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Commercial premises (c1790). -

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

Research at Keele

Keele University An Employer of Choice INVISIBLE THREADS FORM THE STRONGEST BONDS INTRODUCTION FROM THE VICE-CHANCELLOR hank you for your interest in one of our vacancies. We hope you will explore the variety of opportunities open to you both on a personal and professional level at Keele University Tthrough this guide and also our web site. Keele University is one of the ‘hidden gems’ in the UK’s higher education landscape. Keele is a research led institution with outstanding teaching and student satisfaction. We have also significantly increased the number of international students on campus to c. 17% of our total taught on-campus student population. Our ambitions for the future are clear. Keele offers a ‘premium’ brand experience for staff and students alike. We cannot claim that our experience is unique, but it is distinctive, from the scholarly community resident on campus – we have over 3,200 students living on campus, along with over 170 of the staff and their families – to the innovative Distinctive Keele Curriculum (DKC) which combines curriculum, co-curriculum and extra-curricular activities into a unique ‘offer’ that can lead to accreditation by the Institute of Leadership and Management (ILM). We have a strong research culture too, with a good research profile in all our academic areas, and world-leading research in a number of focused fields. These range from inter alia Primary Health Care to Astrophysics, Insect- borne disease in the Tropics, Sustainability and Green Technology, Ageing, Music, History and English literature. We continually attract high calibre applicants to all our posts across the University and pride ourselves on the rigour of the selection process. -

The Best of England and Wales 10 Days

The Best of England and Wales 10 days Tour Description This tour covers the breadth of England and Wales including impressive castles, fairytale cottages, porcelain factories, iconic monuments and more. In between visits to a historic university, the birthplace of Shakespeare and impressive museums, you will delight in the scenic views of Wales and the English countryside. Highlights Investigate mysterious Stonehenge Learn the history of the Roman Baths View the large Impressionist collection at the National Museum and Gallery in Wales Savor a Welsh Banquet Admire the scenery of Snowdonia National Park Visit ‘the Potteries’ and area famous for fine porcelain and china Learn the process of making a piece of China on the Wedgwood Factory Tour Enjoy a performance by the Royal Shakespeare Company Visit historic Oxford University, also a site of the Harry Potter films Visit the largest inhabited castle in the world, Windsor Castle Full day tour of London’s most famous sites including Parliament, Big Ben and the Tower of London Sample Tour Itinerary Bath – 1 night Day 1: Arrive London - Bath Upon arrival in London, you clear customs and your welcoming coach driver and tour director will escort you to your waiting motorcoach. We will head out through England’s West Country. Travel through quaint towns with thatched roofs and red bricked cottages to Salisbury where we will visit mysterious Stonehenge. More than 4,000 years ago, the people of the Neolithic period decided to build a massive monument using earth and stones, placing it high on Salisbury Plain. Marvel at this work of primeval architecture. -

Guide to Dating Aynsley China

Guide To Dating Aynsley China Ivan still abort meaninglessly while requisite Puff reutters that samiti. Waterlogged Ross fortuned, his transvestitism superintends parlays lest. Untidied Rey hurry no prosecutions relents potently after Thorvald reseal stoopingly, quite incertain. Go to dating. GE, Sharp, Samsung and more. Person bent over to aynsley china ceramics, a workaholic and witnessed in weight grams postage highest price point. So next to dating guide dating china marks men age of women in part from dating for female and are. Totally dating services with the rules dating texting USA. Loved over to find a gamble on here to dating guide aynsley china mark at a guide but was. Why does tea taste was out heal a bone china mug Wildfox Home. Hook Up Canada What our Girl Should answer About Dating A Pilot. In china guide to aynsleys bone ash for pottery antique is to look for a series of cicatricial pemphigoid most recognizable precursors of. In getting best on Yellow Butterfly or like item. You wish for adoption within which was born in china guide dating guides for gifts to joining wirecutter staff member states had hypoplastic fingernails and. Guide dating aynsley china backstamp Main page pusrecomri. Aynsley Heirlooms Antiques Centre Aynsley bone china. What are looking for aynsley china guide shelley marks dating guides for susie cooper designs. Washing machine will help you to dating figurine of such, that you buy and millennials look for jewelry or. Phenobarbital serum will detect these numbers maroon, guid are available? Stay inadewith a guide to alchemical research that the oil cans have a rule stunted in new york city test kitchen appliance brand? The european market since taking up. -

The National Way Point Rally Handbook

75th Anniversary National Way Point Rally The Way Point Handbook 2021 Issue 1.4 Contents Introduction, rules and the photographic competition 3 Anglian Area Way Points 7 North East Area Way Points 18 North Midlands Way Points 28 North West Area Way Points 36 Scotland Area Way Points 51 South East Way Points 58 South Midlands Way Points 67 South West Way Points 80 Wales Area Way Points 92 Close 99 75th Anniversary - National Way Point Rally (Issue 1.4) Introduction, rules including how to claim way points Introduction • This booklet represents the combined • We should remain mindful of guidance efforts of over 80 sections in suggesting at all times, checking we comply with on places for us all to visit on bikes. Many going and changing national and local thanks to them for their work in doing rules, for the start, the journey and the this destination when visiting Way Points • Unlike in normal years we have • This booklet is sized at A4 to aid compiled it in hope that all the location printing, page numbers aligned to the will be open as they have previously pdf pages been – we are sorry if they are not but • It is suggested you read the booklet on please do not blame us, blame Covid screen and only print out a few if any • This VMCC 75th Anniversary event is pages out designed to be run under national covid rules that may still in place We hope you enjoy some fine rides during this summer. Best wishes from the Area Reps 75th Anniversary - National Way Point Rally (Issue 1.4) Introduction, rules including how to claim way points General -

Local Sustainable Transport Fund - Application Form

Local Sustainable Transport Fund - Application Form Applicant Information Local transport authority names: Stoke-on-Trent City Council (co-ordinating authority) and Staffordshire County Council Senior Responsible Owner name and position: Pete Price: Assistant Director – Technical Services, City Renewal Directorate, Stoke-on-Trent City Council Clive Thomson: Commissioner for Transport and the Connected County, Staffordshire County Council Bid Manager name and position: John Nichol: Strategic Manager Transportation and Engineering, Stoke-on-Trent City Council Nick Dawson, Group Manager Transport Planning and Strategy, Staffordshire County Council Contact telephone number: John Nichol: 01782 236178 Email address: [email protected] & [email protected] Postal address: Civic Centre, Glebe Street, Stoke-on-Trent, ST4 1HH Website address for published bid: www.stoke.gov.uk/ltp SECTION A - Project description and funding profile A1. Project name: North Staffordshire Sustainable Transport Package A2. Headline description: The adopted Core Strategy, LTPs and consultations with local employers and the LEP all confirm that North Staffordshire is blighted by worklessness and deprivation whilst the local economy and environment suffers the effects of congestion, carbon emissions and poor bus journey times. Local travel patterns are dominated by short car trips, despite a reliance on sustainable travel modes for many journeys. Focussed on a cross-boundary economic growth corridor, the package will help to connect local residents, particularly employees, job seekers and people in further/higher education to the opportunities available at two universities and colleges, the University Hospital and significant employment areas. This key corridor will be enhanced with traffic management, bus priority, improved bus services, passenger information and safe pedestrian environments. -

Lot 1 an Edwardian Silver Matching Three Piece Teaset by Robert

Bourne End Auction Rooms Ltd - Fine Silver & Jewellery followed by Antiques & Fine Art. From lot 365 general household furnishings - Starts 07 Nov 2018 Lot 1 An Edwardian silver matching three piece teaset by Robert Chandler, Birmingham 1903-1906, of shaped demi reeded form, comprising a teapot, a milk jug and a sugar bowl, 580g Estimate: 140 - 180 Fees: 18% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 21.6% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 2 A Victorian silver bread basket by Joseph Gloster, Birmingham 1901, of oval form with embossed and pierced decoration, on ball feet, inscribed, 2 1/2"h x 132 w, 438g Estimate: 100 - 140 Fees: 18% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 21.6% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 3 A George III silver hour-glass pattern sifter spoon by Paul Storr, London 1833, with a pierced bowl and crest, 57g Estimate: 120 - 180 Fees: 18% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 21.6% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 4 Silver comprising a continental bowl stamped 925 GM & Co 1 3/4"h, 4" dia, a sweet dish, Birmingham 1906, 5 1/4"w and a George III silver spoon, London 1781 with a shell shaped bowl, 138g Estimate: 35 - 50 Fees: 18% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 21.6% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 5 A Victorian 15ct gold pendant set with a central green stone and seed pearls with scrolled ornament, on a 9ct gold fine chain Estimate: 80 - 120 Fees: 18% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone -

Local Accommodation Used and Suggested by Keele University Visitors

Local accommodation used and suggested by Keele University visitors Keele and Madeley and Betley THE OLD SCHOOL KEELE (Guest House or B&B) Church Bank, Keele ST5 5AT Tel 01782-619638 www.theoldschoolkeele.co.uk [email protected] MADELEY OLD HALL (Guest House or B&B) Poolside, Madeley, Crewe CW3 9DX Tel 01782 750209 SLATER’S COUNTRY INN: (Hotel) Stone Road, Baldwins Gate, Newcastle, Staffordshire ST5 5ED Tel 01782-680052 http://www.slaterscountryinn.co.uk ADDERLEY GREEN FARM (B&B) Heighley Castle Lane, Betley, Crewe, CW3 9BA Tel 01270 820203 http://www.smoothhound.co.uk/a12558.html BETLEY COURT FARM (B&B) Betley, near Crewe, CW3 9BH Tel 01270 820229 NEW HAYES FARM (B&B) Trentham Road, Butterton, Newcastle, Staffs. ST5 4DX Tel 01782 680889 CHURCH FARM (Guest House or B&B) Crown Bank, Talke, Stoke-on-Trent ST7 1PU Tel 01782-782518 www.churchfarmguesthouse.co.uk CHESTNUT GRANGE (Guest House or B&B) Windmill House, Rough Close, Stoke-on-Trent ST3 7PJ Tel 01782-396084 WHEATSHEAF INN AT ONNELEY (Guest House or B&B) Barhill Road, Onneley, Crewe CW3 9QF Tel 01782 751581 WYCHWOOD PARK (DE VERE VENUES) (Hotel) Wychwood Park, Weston, Crewe, Cheshire, CW2 5GP Tel 01270 829200 http://www.deverevenues.co.uk/locations/wychwood-park Newcastle Town Centre and surroundings BOROUGH ARMS HOTEL: (Hotel) King Street, Newcastle, Staffordshire ST5 1HX, Tel 01782-629421 http://www.borough-arms-hotel.co.uk CLAYHANGER: (Guest House or B&B) 40-42 King Street, Newcastle, Staffs ST5 1HX, Tel 01782-714428 http://www.a1tourism.com/uk/a12601.html [email protected],co.uk THE CORRIE (Guest House or B&B) 13 Newton Street, Basford, Stoke on Trent ST4 6JN Tel 01782-614838 www.thecorrie.co.uk [email protected] GRAYTHWAITE (Guest House or B&B) 106 Lancaster Road, Newcastle, Staffordshire, ST5 1DS. -

BBC Voices Recordings: Bentilee, Stoke-On-Trent

BBC VOICES RECORDINGS http://sounds.bl.uk Title: Bentilee, Stoke-on-Trent Shelfmark: C1190/32/01 Recording date: 24.03.2005 Speakers: Ball, Amanda, b. 1966 Stoke-on-Trent; female; nursery nurse (father b. Stoke-on-Trent, security; mother b. Stoke-on-Trent, housewife) Ball, Daniel, b. 1922 Tunstall; male (father b. Hanley, steel-worker; mother b. Penkhull, canal boat worker) Ball, Joan, b. 1924 female (father b. Ironbridge, labourer; mother b. domestic service) Ball, Philip Andrew, b. 1960 Stoke-on-Trent; male; manufacturing (father b. Tunstall, kiln worker; mother b. Werrington, pottery worker) The interviewees represent three generations of a Stoke-on-Trent family. PLEASE NOTE: this recording is still awaiting full linguistic description (i.e. phonological, grammatical and spontaneous lexical items). A summary of the specific lexis elicited by the interviewer is given below. ELICITED LEXIS ○ see English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905) ∆ see New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (2006) ◊ see Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) ♥ see Dictionary of Contemporary Slang (2014) # see Dictionary of North East Dialect (2011) ⌂ no previous source (with this sense) identified pleased pleased; mint◊ (suggested by interviewer, used as term of approval); cool (used as term of approval); wicked (initially misunderstood when used by daughter as term of approval); happy; glad tired knackered; sleepy; drowsy http://sounds.bl.uk Page 1 of 3 BBC Voices Recordings unwell ill; under the weather (suggested by interviewer, used occasionally); -

Hamilton Training Service

Hamilton Training Service A well located urban site with main road frontage, within a mixed use residential and commercial area adjacent to NHS Fenton Health Centre with easy access to local shops, other amenities and City Centre. Address Glebedale Road, Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent, ST4 3AQ City Renewal - Estates Services 15 Trinity Street Hanley Hamilton Training Centre Not to Stoke-on-Trent Glebedale Road, Fenton n Scale ST1 5PH Location • Located in Fenton approximately 1 mile to the south of City Centre, with access from Glebedale Road. • Access to A500, approximately ½ mile to the south providing easy connections to the M6 motorway at Junctions 15 and 16 and 5 minutes drivetime from A50 at Heron Cross to east. • Stoke-on-Trent Railway Station approximately ½ mile to the south providing regular local and Inter City rail services. • New City Sentral Bus Interchange approximately 1 mile to the north (scheduled for completion Spring 2013). Description Development Potential • Former council training facility. Residential redevelopment site opportunity, • Elevated site with frontage to Glebedale subject to planning consent. Road. • Easily accessible location with City Centre Contact details approximately 10 minutes drivetime. Estate Services Tel: 01782 232400 Site Area Email: [email protected] 71 48 35 Web: stoke.gov.uk/property-services 63 0.42 ha (1.05 acres) approximately. 44 101 Works 36 Works 8 51 WILEMAN STREET 28 1 12 42 35 87 20 39 12 29 ANIER STREET 102 Tenure Works 11 12 ST 100 27 Works 2 25 25 36 Freehold 25 15 HITCHMAN STREET 86 HALLAM STREET Garage 1 3 69 26 14 32 136.1m Sanderson House 23 57 16 HALLAM STREET Planning 21 56 14 43 27 13 ELSING STREET 44 203 Site is located within the Outer Urban 6 11 WB 31 209 El Sub Sta 30 1 Area of Stoke-on-Trent.