6 Lessons from Karachi: the Role of Demonstration, Documentation, Mappi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools JUL 0 2 2003

Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri B.S. Architecture Studies University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2001 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2003 JUL 0 2 2003 Copyright@ 2003 Mahjabeen Quadri. Al rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Mahjabeen Quadri Departm 4t of Architecture, May 19, 2003 Certified by:- Reinhard K. Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Julian Beinart Departme of Architecture Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students ROTCH Thesis Committee Reinhard Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Edith Ackermann Visiting Professor Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Anna Hardman Visiting Lecturer in International Development Planning Department of Urban Studies and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Hashim Sarkis Professor of Architecture Aga Khan Professor of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism Harvard University Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 23, 2003 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies Abstract Pakistan's greatest resource is its children, but only a small percentage of them make it through primary school. -

SEF Assisted Schools (SAS)

Sindh Education Foundation, Govt. of Sindh SEF Assisted Schools (SAS) PRIMARY SCHOOLS (659) S. No. School Code Village Union Council Taluka District Operator Contact No. 1 NEWSAS204 Umer Chang 3 Badin Badin SHUMAILA ANJUM MEMON 0333-7349268 2 NEWSAS179 Sharif Abad Thari Matli Badin HAPE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE ASSOCIATION 0300-2632131 3 NEWSAS178 Yasir Abad Thari Matli Badin HAPE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE ASSOCIATION 0300-2632131 4 NEWSAS205 Haji Ramzan Khokhar UC-I MATLI Matli Badin ZEESHAN ABBASI 0300-3001894 5 NEWSAS177 Khan Wah Rajo Khanani Talhar Badin HAPE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE ASSOCIATION 0300-2632131 6 NEWSAS206 Saboo Thebo SAEED PUR Talhar Badin ZEESHAN ABBASI 0300-3001894 7 NEWSAS175 Ahmedani Goth Khalifa Qasim Tando Bago Badin GREEN CRESCENT TRUST (GCT) 0304-2229329 8 NEWSAS176 Shadi Large Khoski Tando Bago Badin GREEN CRESCENT TRUST (GCT) 0304-2229329 9 NEWSAS349 Wapda Colony JOHI Johi Dadu KIFAYAT HUSSAIN JAMALI 0306-8590931 10 NEWSAS350 Mureed Dero Pat Gul Mohammad Johi Dadu Manzoor Ali Laghari 0334-2203478 11 NEWSAS215 Mureed Dero Mastoi Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION AND REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 12 NEWSAS212 Nabu Birahmani Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION & REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 13 NEWSAS216 Phullu Qambrani Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION AND REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 14 NEWSAS214 Shah Dan Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION AND REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 15 RBCS002 MOHAMMAD HASSAN RODNANI -

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

The BCCI Affair

The BCCI Affair A Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate by Senator John Kerry and Senator Hank Brown December 1992 102d Congress 2d Session Senate Print 102-140 This December 1992 document is the penultimate draft of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee report on the BCCI Affair. After it was released by the Committee, Sen. Hank Brown, reportedly acting at the behest of Henry Kissinger, pressed for the deletion of a few passages, particularly in Chapter 20 on "BCCI and Kissinger Associates." As a result, the final hardcopy version of the report, as published by the Government Printing Office, differs slightly from the Committee's softcopy version presented below. - Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists This report was originally made available on the website of the Federation of American Scientists. This version was compiled in PDF format by Public Intelligence. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF INVESTIGATION ............................................................................... 21 THE ORIGIN AND EARLY YEARS OF BCCI .................................................................................................... 25 BCCI'S CRIMINALITY .................................................................................................................................. 49 BCCI'S RELATIONSHIP WITH FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS CENTRAL BANKS, AND INTERNATIONAL -

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

Malir-Karachi

Malir-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Malir Karachi Gadap Town NA 408180381 GBLSS - HUSSAIN BLAOUCH Middle Boys 14,324 2,865 8,594 5,729 2,865 11,459 45,836 11,459 57,295 2 Malir Karachi Gadap Town NA 408180436 GBELS - HAJI IBRAHIM BALOUCH Elementary Mixed 24,559 4,912 19,647 4,912 4,912 19,647 78,588 19,647 98,236 3 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180426 GBELS - HASHIM KHASKHELI Elementary Boys 42,250 8,450 33,800 8,450 8,450 33,800 135,202 33,800 169,002 4 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180434 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.3 OLD Elementary Mixed 35,865 7,173 28,692 7,173 7,173 28,692 114,769 28,692 143,461 5 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180435 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.3 NEW Elementary Mixed 24,882 4,976 19,906 4,976 4,976 19,906 79,622 19,906 99,528 6 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 2-Darsano Channo 408180073 GBELS - AL-HAJ DUR MUHAMMAD BALOCH Elementary Boys 36,374 7,275 21,824 14,550 7,275 29,099 116,397 29,099 145,496 7 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 2-Darsano Channo 408180428 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.1 Elementary Mixed 33,116 6,623 26,493 6,623 6,623 26,493 105,971 26,493 132,464 8 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 3-Gujhro 408180441 GBELS - SIRAHMED VILLAGE Elementary Mixed 38,725 7,745 30,980 7,745 7,745 30,980 123,919 -

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

Be Where the Growth Is Be Where the Growth Is

Be Where the Growth is Small & Mid Cap Large Cap Gold Debt Visual is for illustration purpose only. Nippon India Asset Allocator FOF (An open ended fund of funds scheme investing in equity oriented schemes, debt oriented schemes and gold ETF of Nippon India Mutual Fund) Performance of various Asset Classes and Sub Asset Classes keep changing over time. Even the best of minds cannot always predict which asset class will do well. But we have a solution for you! Nippon India Asset Allocator FoF invests across Equity oriented schemes, Debt oriented schemes and Gold ETF of Nippon India Mutual Fund with the help of an in-house proprietary model. This model decides allocation across Large Cap, Mid Cap, Small Cap, Short Term Debt, Long Term Debt and Gold ETF. This dynamic framework uses a robust set of Macro, Micro & Market Indicators with an aim to deliver superior risk adjusted returns. This ensures that you are always invested in the asset classes where the growth is most likely to be! NFO Opens On:18th January'21 | NFO Closes On:1st February'21 For more information, contact your mutual fund distributor or visit: mf.nipponindiaim.com Investors will be bearing the recurring expenses of the scheme in addition to the expenses of underlying schemes. Nippon India Asset Allocator FoF (An open ended fund of funds scheme investing in equity oriented schemes, debt oriented schemes and gold ETF of Nippon India Mutual Fund) Nippon India Asset Allocator FoF is suitable for investors who are seeking*: • Long term capital growth • An open ended fund of funds scheme investing in equity oriented schemes, debt oriented schemes and Gold ETF of Nippon India Mutual Fund Investors understand that their principal *Investors should consult their financial advisors if in doubt about whether the product is suitable for them. -

Services for the Urban Poor a People-Centred Approach by George Mcrobie

Services for the Urban Poor A People-centred Approach by George McRobie George McRobie was educated in Scotland. At the age Contents of 17 he began to work in the coal mines. He studied as an evening student and earned a degree at London Preface 4 School of Economics in his 20s. In 1956 he became assistant to E.F. Schumacher, then Acknowledgements 4 Economic Adviser to the National Coal Board, and 10 1 Introduction 4 years later helped him form the Intermediate Technol- Problem 4 ogy Group in London. He left the Coal Board to work Method 5 on small industry development in India, and during his Organization of the Report 5 three years there, started the Appropriate Technology Development Association of India. In 1968 he returned 2 General Considerations 5 to London as an executive Director of the Intermediate The Urban Poor and Health 5 Technology Group. On Schumacher’s death in 1977, Different Strategies for Providing Services 6 McRobie became Chairman of the Group and published Appropriate Technologies for Service Provision 7 Small is Possible, a sequel to Schumacher’s Small is Water Supply 7 Beautiful. Sanitation 8 He has worked for many years as a consultant on ap- Household Garbage 10 propriate technology and rural development in Africa, Costs of Service Options 11 Asia and Latin America. He serves on the governing bodies of Intermediate Technology, the India Develop- 3 Recommendations 12 ment Group, the New Economics Foundation and the Community Involvement and the Role of Soil Association, and two non-profit companies promot- Government 12 ing appropriate technologies in Europe and the Third Design of a Community-Based Programme 13 World, Technology Exchange and the Bureau of Knowl- Implementation of a Community- edge and Finance. -

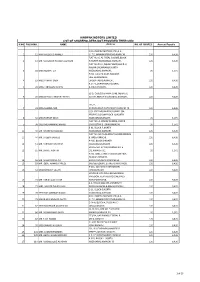

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR.