Someday We'll Look Back on This and Laugh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bossypants? One, Because the Name Two and a Half Men Was Already Taken

Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully thank: Kay Cannon, Richard Dean, Eric Gurian, John Riggi, and Tracy Wigfield for their eyes and ears. Dave Miner for making me do this. Reagan Arthur for teaching me how to do this. Katie Miervaldis for her dedicated service and Latvian demeanor. Tom Ceraulo for his mad computer skills. Michael Donaghy for two years of Sundays. Jeff and Alice Richmond for their constant loving encouragement and their constant loving interruption, respectively. Thank you to Lorne Michaels, Marc Graboff, and NBC for allowing us to reprint material. Contents Front Cover Image Welcome Dedication Introduction Origin Story Growing Up and Liking It All Girls Must Be Everything Delaware County Summer Showtime! That’s Don Fey Climbing Old Rag Mountain Young Men’s Christian Association The Windy City, Full of Meat My Honeymoon, or A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again Either The Secrets of Mommy’s Beauty Remembrances of Being Very Very Skinny Remembrances of Being a Little Bit Fat A Childhood Dream, Realized Peeing in Jars with Boys I Don’t Care If You Like It Amazing, Gorgeous, Not Like That Dear Internet 30 Rock: An Experiment to Confuse Your Grandparents Sarah, Oprah, and Captain Hook, or How to Succeed by Sort of Looking Like Someone There’s a Drunk Midget in My House A Celebrity’s Guide to Celebrating the Birth of Jesus Juggle This The Mother’s Prayer for Its Daughter What Turning Forty Means to Me What Should I Do with My Last Five Minutes? Acknowledgments Copyright * Or it would be the biggest understatement since Warren Buffett said, “I can pay for dinner tonight.” Or it would be the biggest understatement since Charlie Sheen said, “I’m gonna have fun this weekend.” So, you have options. -

DK Reinemer Agency Contact: [email protected] (503) 780-7555

DK Reinemer Agency Contact: [email protected] (503) 780-7555 www.ActorsInAction.com Height: 5’10” Eye Color: Green Shoes: 10.5 Weight: 180 Hair: Blonde Clothing Size: M Acting: Television/Film Chelsea Netflix Co-star Netflix Dark Darkness (Pilot) Lead D4 Productions Bad Cop (sketch) Lead LaughsTV Silver Reef Casino Lead HandCrank Films Web Flerp Films (Ep. 1 & 2) Lead Various Sketches Dark Darkness Ronald Web Series Butte’re Model Funny or Die! ATM Guy Funny or Die! The Neighborhood Chad Channel 101 Live Stage Help! I’m American Actor/Writer National Tour 100% Stuff (House sketch team) Actor/Writer Pack Theater DK and Morgan Show (Int. Tour Co.) Actor/Writer SF Sketchfest Ryan Stiles and Friends Ensemble Ryan Stiles 48 hour Sketch Fest Actor/Writer iO West NoHo Comedy ShowHo Host/Writer ACME NoHo Training: UCB: Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre Los Angeles - Advanced Improv/Musical improv - Teachers: Alex Berg, Johnny Meeks, Joel Spence, Will Hines, Will McClaughlin, Tara Copeland, Rebecca Drysdale The Pack Theatre - Advanced Improv/Sketch Writing - Teachers: Miles Stroth, Eric Moneypenny, Heather Anne Campbell, Sam Brown, Brian O’Connell, Fairhaven College Western Washington University - BA Writing/Film/Acting - Social Justice/The Individual in Society Special Skills Guitar, improv, sketch comedy, juggling, soccer, baseball, basketball, football, swimming, yoga, knitting, hiking, camping, golf, chef, dance, sing, painting, swimming, running, weightlifting, card games, massage, meditation, driving stick shift, carpentry, construction, lawn care, snowboarding, skiing, sledding, fishing, bicycle riding.. -

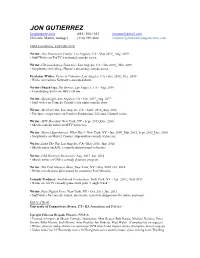

JON GUTIERREZ Jongutierrez.Com (845) 300-1683 [email protected] Christine Martin, Manager (310) 919-4661 [email protected]

JON GUTIERREZ Jongutierrez.com (845) 300-1683 [email protected] Christine Martin, manager (310) 919-4661 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Writer, This Functional Family, Los Angeles, CA • May 2019_ Aug. 2019 • Staff Writer on TruTV’s animated comedy series. Writer, Ultramechatron Team Go!, Los Angeles, CA • Jan. 2019_ Mar. 2019 • Scriptwriter on College Humor’s streaming comedy series. Freelance Writer, Victor & Valentino, Los Angeles, CA • Oct. 2018_ Dec. 2018 • Writer on Cartoon Network’s animated show. Writer (Punch Up), The Detour, Los Angeles, CA • Aug. 2018 • Contributing writer on TBS’s sitcom. Writer, @midnight, Los Angeles, CA • Feb. 2017_Aug. 2017 • Staff writer on Comedy Central’s late night comedy show. Writer, My Crazy Sex, Los Angeles, CA • April. 2016_Aug. 2016 • Freelance script writer on Painless Productions’ Lifetime Channel series. Writer, MTV Decoded, New York, NY • Sept. 2015_Dec. 2016 • Sketch comedy writer on MTV webseries. Writer, Marvel Superheroes: What The!?, New York, NY • Jan. 2009_May 2012, Sept. 2015_Dec. 2016 • Scriptwriter on Marvel Comics’ stop-motion comedy webseries. Writer, Land The Gig, Los Angeles, CA • May 2016_June 2016 • Sketch writer on AOL’s comedy/instructional webseries. Writer, CBS Diversity Showcase • Aug. 2015_Jan. 2016 • Sketch writer on CBS’s comedy diversity program. Writer, The Paul Mecurio Show, New York, NY • May 2014_Oct. 2014 • Writer on talk show pilot hosted by comedian Paul Mecurio. Comedy Producer, NorthSouth Productions, New York, NY • Apr. 2013_ May 2013 • Writer on TruTV comedy game show pilot “Laugh Truck.” Writer, Fuse Digital News, New York, NY • Oct. 2011_Jan. 2013 • Staff writer for comedy videos, interviews, news hits and promos for online and onair. -

Cast List, Bios & Reels

Cast List, Bios & Reels Adrian Frimpong A willing participant Bio Adrian’s a Ghanaian-American comedian based out of New York. He has written and performed comedy at San Francisco Sketchfest, Portland Sketchfest, and Out of Bounds in Austin. He’s also been seen in ComedyCentral’s Mini Mocks, and NBC’s Bring the Funny, as well as a bit role on Late Night with Seth Meyers. Website, Social, Reels, Etc. Website | IMDB | Instagram Alex Song-Xia Doing better, thanks Bio Alex is a writer, actor, and comedian based in New York and has written for TV shows including The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, It's Personal with Amy Hoggart, and HBO’s Night of Too Many Stars. As an actor, Alex can be seen in The Week Of (Netflix), starring Adam Sandler and Chris Rock, and High Maintenance (HBO). Alex trained at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre, where she was a house team performer and writer, member of the UCB Touring Company, and co-host and producer of the variety show Asian AF, and the William Esper Studio in New York. Website, Social, Reels, Etc. Website | Reel | IMDB | Photos | Instagram | Twitter Dan Fox Brings the fun(ny) Bio Dan Fox is a comedian based in Brooklyn, New York. He spent the last decade performing at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre, both as an actor on Maude Night and as a writer/actor/creator of An Evening With The Trumpet Boys, a show The New York Times called, "...a hilarious night of sketch comedy." Dan has interviewed celebrities for Yahoo! Movies, written a children's book about the dangers of phone addiction, and hosts his very own talk show called The Late Afternoon Show. -

Upright Citizens of the Digital Age: Podcasting and Popular Culture in an Alternative Comedy Scene

Upright Citizens of the Digital Age: Podcasting and Popular Culture in an Alternative Comedy Scene BY Copyright 2010 Vince Meserko Submitted to the graduate degree program in Communication Studies and the Graduate Faculty at the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts ________Dr. Jay Childers, PhD____________ Chairperson _____ Dr. Nancy Baym, PhD____________ ______ Dr. Suzy D’Enbeau, PhD____________ Committee members Date Defended: ____August 1, 2010___ ii The Thesis Committee for Vince Meserko certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Upright Citizens of the Digital Age: Podcasting and Popular Culture in an Alternative Comedy Scene _____Dr._Jay Childers, PhD____ Chairperson Date approved:___August 1, 2010 _______ iii Abstract In this thesis I look at how one of our newest communication mediums, the podcast, is being used by a group of Los Angeles-based comedians loosely assembled under the “alternative comedy” label. Through the lens of critical and medium theory, I identify two primary functions of the podcast for this community: 1) as a space for comedy performance involving character- based sketches and stream-of-consciousness conversation and 2) as a meditation on the nature of stand-up comedy that often confronts tensions between popular and folk culture. I argue that these two functions have become generic hallmarks of the alternative comedy podcasting community. As such, they provide important insight into how subcultures reinforce, reinterpret, and manage artistic value in new media environments. Further, the podcast offers an object lesson in the ways that creative artists have exercised a new sense of agency in controlling the direction of their careers. -

Lesley Tsina Web Resume 2012

Lesley Tsina SAG-AFTRA [email protected] Television Funny or Die Presents: Designated Driver Co-Star HBO/Dir. Jason Woliner New Media Asperger’s High Lead Dir. Jason Axinn Scary Girl with Chloe Moretz Supporting Dir. Ryan Perez Prime Suspect: The Hat Lead Dir. Lowell Meyer Murder List Lead Dir. Ryan Perez Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Trailer Supporting Dir. Aaron Greenberg Kate Plus 8 College Years Supporting Dir. Robert Mercado Elevator (webseries) Supporting Dir. Woody Tondorf Election 2008 Ground Zero Supporting Dir. Tom Gianas Craigslist Penis Photographer Featured Dir. Eric Appel Funeral Sex Supporting Dir. Jason Axinn Comedy CBS Diversity Showcase 2012 Sketch Performer CBS/Rick Najera Ask a Hedge Fund Manager (sketch) Sketch Performer NPR - Marketplace Maude Night Sketch Team Member Upright Citizens Brigade Harold Night Improv Team Member Upright Citizens Brigade Lord of the Files Solo Performer Comedy Central Stage Tournament of Nerds Sketch Performer Upright Citizens Brigade Extreme Tambourine Sketch Performer Comedy Central Stage Slave Leia Improv Team Member IO West – Mainstage SF Sketchfest – Extreme Tambourine Sketch Performer Dark Room, SF San Francisco Improv Festival Improv Performer Eureka Theatre, SF Comedy Death-Ray Stand-up Comic Upright Citizens Brigade Hothouse Comedy Show Stand-up Comic RZO/Hothouse Tomorrow Show Stand-up Comic Steve Allen Theatre Commercials Conflicts available upon request. Training Improv Comedy Upright Citizens Brigade: Matt Besser, Matt Walsh, Ian Roberts, Andy Daly, Dannah Feinglass, Seth Morris IO West: Derek Miller, Dave Hill On-Camera Margie Haber Studios: Saxon Trainor, Annie Grindlay Acting Risa Bramon-Garcia Commercial Khristopher Kyer, Jill Alexander Political Musical Theatre San Francisco Mime Troupe Workshop B.A. -

Download Upright Citizens Brigade Comedy Improvisation Manual PDF

Download: Upright Citizens Brigade Comedy Improvisation Manual PDF Free [248.Book] Download Upright Citizens Brigade Comedy Improvisation Manual PDF By Matt Walsh, Ian Roberts, Matt Besser Upright Citizens Brigade Comedy Improvisation Manual you can download free book and read Upright Citizens Brigade Comedy Improvisation Manual for free here. Do you want to search free download Upright Citizens Brigade Comedy Improvisation Manual or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #Upright Citizens Brigade Comedy Improvisation Manual | #13370 in Books | 2013 | PDF # 1 | File type: PDF | 384 pages | |0 of 0 people found the following review helpful.| Received a somewhat worn copy, but luckily I have low standards! | By Sara |I ordered this from UCB improv for a gift. Unfortunately the book shows signs of wear, including a bent corner on the back cover and several scratches and indentations on the front. The spine seems intact and the pages seem well preserved, though, so I'm not going to return it. It's not a huge deal, and I' The Upright Citizens Brigade Comedy Improvisation Manual is a comprehensive guide to the UCB style of long form comedy improvisation. Written by UCB founding members Matt Besser, Ian Roberts, and Matt Walsh, the manual covers everything from the basics of two person scene work (with a heavy emphasis on finding "the game" of the scene), to the complexities of working within an ensemble to perform long form structures, such as "The Harold" and "The Movie". -

Downloadable Résumé

ILIANA INOCENCIO SAG-AFTRA Height: 5’3 | Eyes: Brown | Hair: Black th Legit & Literary: Take 3 Talent Agency 646.289.3915 • 1411 Broadway, 16 Floor, New York, NY 10018 Management: MultiEthnic Talent 917.689.8459 • Commercial: Ingber and Associates 212.889.9450 www.ilianainocencio.com FILM & TELEVISION The Iliza Shlesinger Sketch Show Recurring Netflix The Tonight Show w/ Jimmy Fallon Recurring NBC Kal Penn Approves this Message Co-Star Freeform/Hulu The Other Two Co-Star Comedy Central New Amsterdam Co-Star NBC/Dir: Don Scardino Orange is the New Black Co-Star Netflix Girl Code Co-star MTV THEATER Broadway Bares XXII Singer/Dancer Roseland Ballroom/ Dir: Jerry Mitchell Story Pirates Company Actor Symphony Space/Various AzN PoP! Baby Rice/Co-creator Joe’s Pub at The Public Theater A Christmas Carol Fred’s Sister Ford’s Theater/Dir: Matt August Hair Tribe ReVision Theater The King and I Ensemble The Ogunquit Playhouse Bernstein’s Mass Latin Chorus Kennedy Center/Dir: Murray Sidlin Asian and…(Reading) Lead The Cherry Lane Theatre NEW MEDIA Women at Work Lead Bustle Chip and Dean Lead FrankenMel Productions Baby Shower Rebellion Lead Refinery29 Flying High w/ Charlie Lead OutliciousTV COMEDY Decoded w. Francesca Ramsey Season 2 Writer MTV NBC/UCB Diversity Showcase Original Characters NBC/Upright Citizens Brigade NBC/PIT Diversity Showcase Original Characters NBC/The People’s Improv Theater IFC Comedy Showcase AzN PoP! IFC AzN PoP! Live in Concert! Baby Rice/Co-Creator Upright Citizens Brigade NY/LA Maude Night (UCB House Team) Company -

Ele Woods Sag, Aea-E

ELE WOODS SAG, AEA-E Seeking Representation Hair: Brown Eyes: Green/Hazel _______________________________________________________________________________________ FILM Unlovable Supporting Director, Suzi Yoonessi Rivergreaser Lead Director, Nick Rasmussen TELEVISION Brews Brothers Guest Star Director, Rob Cohen/Netflix American Princess Recurring Director, Various/ Lifetime Jimmy Kimmel Live Day Player Director, Various/ABC Still Laugh-In Featured Performer Various/ Netflix Will Vs. The Future Guest Star Director, Joe Nussbaum/Amazon The Good Place CoStar Director, Dean Holland/NBC Adam Ruins Everything CoStar Director, Matthew Pollack/TruTV The 2016 MTV Movie Awards Featured Performer Director, Glenn Weiss/MTV NEW MEDIA You and Your Best Friend Star Director, Michael Shaubauch, Snapchat Turnt Up With the Taylors Series Regular Director, Danny Daneau/ Facebook Do You Want to See a Dead BodyGuest Star Director, Nicolas Jasenovec/YoutubeRed Hot Tipz w/ Chris Kattan Day Player Director, Fax Bahr/FunnyorDie CollegeHumor Day Player Director, Various/CollegeHumor Drive Share Guest Star Director, Paul Scheer & Rob Huebel/VGo90 Take My Wife Recurring Dir. Sam Zwiebleman & Ingrid Jungermann UCB Show Day Player Director, Matt Besser/ Seeso THEATRE Maude Night House Team Performer Upright Citizen’s Brigade, Los Angeles Bachelor the Musical Lauren M Various, Los Angeles Victory! Nell Gwynn Atlantic Theatre, New York City Hairspray Velma VonTussle Town Hall Theatre, VT TRAINING Independent Shakespeare Company of Los Angeles - Ongoing training, Joseph Culliton Upright Citizens Brigade - Since 2008: Advanced Study Program, Diversity Program alumni. The Groundlings -Annie Sertich, Jordan Black (Advanced Lab) BA in Theatre from Middlebury College Clowning - Cirque Troc, Reignier France. SPECIAL SKILLS Improv, Var. Dance, Clowning, Roller skating/blading, Dodgeball, Snowboarding, Basketball, Soprano/Alto, Stage combat trained. -

Rob Reese Playwright

hellorobreese.com ROB REESE [email protected] Playwright /Librettist Musical & Opera (representative): Murder In the Key of Death (librettist) Opera On Tap New York, NY Miranda (co librettist w/ Kamala Sankaram) HERE Arts Center New York, NY Yahweh’s Follies (Book & Lyrics) Ars Nova New York, NY Theater (representative): 101 Reasons to Thank God for Donald J Trump, The Brick Theater New York, NY Vladmir J Putin, & My Dad Who’s a Dick. The Black Hole The Flea Theater New York, NY Survivor: Vietnam!* ‡ The People’s Improv Theater New York, NY Keanu Reeves Saves the Universe The Basement Theatre Auckland, NZ Keanu Reeves Saves the Universe The Red Room New York, NY Frankenstein** ‡ The Actor’s Studio Kuala Lumpur, MY Frankenstein**‡ Pelican Theater New York, NY Tad Granite: Private Eyeball – The Radio Plays The People’s Improv Theater New York, NY Invasion of the Yellow Menace Stir Friday Night Productions Los Angeles, CA Pantheon of Convenience B.S. Int’l Improv Fest. Austin, TX Birth of the Yellow Menace Stir Friday Night Productions Chicago, IL Return of the Yellow Menace Stir Friday Night Productions Chicago, IL The Game The “O” Theater Chicago, IL The Camp Strawdog Theatre Chicago, IL Television / Video / Short Film Make Your Move Phoenix Public Television Phoenix, AZ Sundays @ The Parkside Online Serial Amnesia Wars: Small Content Video Projects Small Content Video Keanu Reeves Saves the Universe: Special Reunion Special Short Film Publications: ‡Indie Theatre Now: Frankenstein and Survivor: Vietnam! each available on-demand at http://www.indietheaternow.com/ **Playing with Canons: Explosive New Works from Great Literature by America's Indie Playwrights Anthology includes Frankenstein *Plays and Playwrights 2004 Anthology includes Survivor: Vietnam! Awards / Grants: Miranda received the 2012 Innovative Theater Award for Outstanding Production of a Musical. -

A Look at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre and Hidden Collections of Improv Comedy

Never Done Before, Never Seen Again: A Look at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre and Hidden Collections of Improv Comedy By Caroline Roll A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program Department of Cinema Studies New York University May 2017 1 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Chapter 1: A History of Improv Comedy ...……………………………………………………... 5 Chapter 2: Improv in Film and Television ...…………………………………………………… 20 Chapter 3: Case Studies: The Second City, The Groundlings, and iO Chicago ...……………... 28 Chapter 4: Assessment of the UCB Collection ……………..………………………………….. 36 5: Recommendations ………..………………………………………………………………….. 52 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………………... 57 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………………………… 60 Acknowledgements …...………………………………………………………………………... 64 2 Introduction All forms of live performance have a certain measure of ephemerality, but no form is more fleeting than an improvised performance, which is conceived in the moment and then never performed again. The most popular contemporary form of improvised performance is improv comedy, which maintains a philosophy that is deeply entrenched in the idea that a show only happens once. The history, principles, and techniques of improv are well documented in texts and in moving images. There are guides on how to improvise, articles and books on its development and cultural impact, and footage of comedians discussing improv in interviews and documentaries. Yet recordings of improv performances are much less prevalent, despite the fact that they could have significant educational, historical, or entertainment value. Unfortunately, improv theatres are concentrated in major cities, and people who live outside of those areas lack access to improv shows. This limits the scope for researchers as well. -

Vacaville Performing Arts Theatre 1010 Ulatis Drive Vacaville, CA 95687 Box Office (707) 469-4013

Vacaville Performing Arts Theatre 1010 Ulatis Drive Vacaville, CA 95687 Box Office (707) 469-4013 For Immediate Release Contact: Desiree Tinder January 6, 2014 707-469-4015 Vacaville Performing Arts Theatre Chases the Winter Blues With Upright Citizens Brigade Touring Company Laugh your way into the New Year at Vacaville Performing Arts Theatre with the greatest producer of comedians in America, the Upright Citizens Brigade, whose touring troupe brings its hilarious improv and sketch comedy to clubs and theaters across the nation and now to Vacaville. Named “Hot Farm Team” by Rolling Stone and a wellspring of some of the funniest actors and writers on Saturday Night Live, The Office and The Daily Show, Upright Citizens Brigade Touring Company brings down the house and perhaps the whole city with its outrageous sketch comedy. Comedian Conan O’Brien quips that this is “… the type of manic, original, inventive stuff I’m always interested in.” The Upright Citizens Brigade Touring Company’s performance takes place at 8 p.m. Thursday, January 30. The Upright Citizens Brigade Touring Company show lasts about 90 minutes and consists of two hilarious halves of the freshest, longform improv the nation has to offer. The Touring Company cast is hand-picked from the best improv comedians in New York City and Los Angeles; these performers are the “next wave” of comedy superstars from the theatre that introduced comedian greats such as Amy Poehler, Horatio Sanz (Saturday Night Live), Rob Corddry (The Daily Show), Ed Helms (The Daily Show, The Office), Rob Riggle (Saturday Night Live, The Daily Show), Paul Scheer & Rob Huebel (Best Week Ever) and many more to the lexicon of household comedy names.