Corsham Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to the Stars of the Screen

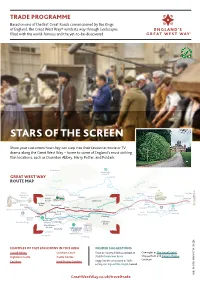

TRADE PROGRAMME Based on one of the first Great Roads commissioned by the Kings of England, the Great West Way® winds its way through landscapes filled with the world-famous and the yet-to-be-discovered. STARS OF THE SCREEN Show your customers how they can step into their favourite movie or TV drama along the Great West Way – home to some of England’s most striking film locations, such as Downton Abbey, Harry Potter, and Poldark. Cheltenham BLENHEIM PALACE GREAT WEST WAY Oxford C otswolds ns ROUTE MAP ter hil C e Th Clivedon Clifton Marlow Big Ben Suspension Westonbirt Malmesbury Windsor Paddington Bridge Swindon Castle Henley Castle LONDON Combe Lambourne on Thames wns Eton Dyrham ex Do ess College BRISTOL Park Chippenham W rth Windsor Calne Avebury No Legoland Marlborough Hungerford Reading KEW Brunel’s SS Great Britain Heathrow GARDENS Corsham Bowood Runnymede Ascot Richmond Lacock Racecourse Bristol BATH Newbury ROMAN Devizes Pewsey BATHS Bradford Highclere Cheddar Gorge on Avon Trowbridge Castle Ilford Manor Gardens Westbury STONEHENGE & AVEBURY Longleat WORLD HERITAGE SITE Stourhead Salisbury EXAMPLES OF FILM LOCATIONS IN THIS AREA INSIDER SUGGESTIONS Lacock Abbey Corsham Court Feast on hearty British pub food at Overnight at The Angel Hotel, Highclere Castle Castle Combe stylish Carnarvon Arms Chippenham and Guyers House, Corsham Corsham Iford Manor Gardens Enjoy fine British cuisine at 15th- centry inn Sign of the Angel, Lacock GreatWestWay.co.uk/traveltrade SCREEN MAMMOTH MAIN PHOTO: DAY ONE DAY TWO LACOCK & HIGHCLERE CASTLE CORSHAM & CASTLE COMBE Drive four miles west of Lacock to Corsham, a market town complete with honey-stone buildings and cobbled high street. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 a DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY In Trade: Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Emma Goldsmith EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2017 2 Abstract This dissertation provides an account of the richest people in Glasgow and Liverpool at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. It focuses on those in shipping, trade, and shipbuilding, who had global interests and amassed large fortunes. It examines the transition away from family business as managers took over, family successions altered, office spaces changed, and new business trips took hold. At the same time, the family itself underwent a shift away from endogamy as young people, particularly women, rebelled against the old way of arranging marriages. This dissertation addresses questions about gentrification, suburbanization, and the decline of civic leadership. It challenges the notion that businessmen aspired to become aristocrats. It follows family businessmen through the First World War, which upset their notions of efficiency, businesslike behaviour, and free trade, to the painful interwar years. This group, once proud leaders of Liverpool and Glasgow, assimilated into the national upper-middle class. This dissertation is rooted in the family papers left behind by these families, and follows their experiences of these turbulent and eventful years. 3 Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the advising of Deborah Cohen. Her inexhaustible willingness to comment on my writing and improve my ideas has shaped every part of this dissertation, and I owe her many thanks. -

Newsletter 214 May 2019

The Furniture History Society Newsletter 214 May 2019 In this issue: A South German Drawing for a Cupboard with Auricular Carving for the Rijksmuseum | Society News | A Tribute | Future Society Events | Occasional and Overseas Visits | Other Notices | Book Reviews | Reports on the Society’s Events | Publications | Grants A South German Drawing for a Cupboard with Auricular Carving for the Rijksmuseum hen a group from the Furniture contribution to the Rijksmuseum’s WHistory Society visited Amsterdam in Decorative Art Fund. Fittingly, this has July 2018 on the occasion of the exhibition been deployed towards the purchase of a ‘Kwab, Dutch Design in the Age of German drawing showing a cupboard with Rembrandt’ at the Rijksmuseum, they ‘kwab’, or rather Ohrmuschelstil, carvings. spent an afternoon in the museum’s print room studying a selection of drawings showing furniture designs. This was no self-evident part of the programme: until recently, the Rijksmuseum had no collection of drawn designs for the decorative arts to speak of, although some fine examples have long been kept among the general holdings of Old Master drawings. However, in order to remedy this situation as best as possible, in 2013 the Rijksmuseum Decorative Art Fund was established by private benefactors, with the express purpose of purchasing European design drawings from 1500–1900.1 Over the past six years, a considerable number have been acquired, and, although the collection is still in its infancy, it was possible to put together a display of about thirty-five furniture drawings, ranging from a late sixteenth-century Parisian design for a cupboard to some late nineteenth-century Fig. -

Capability Brown

Capability Brown Out of the 170 Capability Brown worked on, some of the most well-known gardens created include: - Blenheim Palace - Oxfordshire Set in the Oxfordshire Cotswolds, Blenheim Palace is considered to be one of the finest baroque houses in the country. It was a gift from Queen Anne and a grateful nation to John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, in recognition of his famous victory over the French at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. It is now the home of the 11th Duke of Marlborough and is lived in and cared for by the family for whom it was built. Inside the Palace can be found a superb collection of tapestries, paintings, porcelain and furniture in the magnificent State Rooms. In 1764, the 4th Duke brought Lancelot “Capability” Brown to make major changes to Palace Park and Gardens. Brown transformed the park by making the canal into a serpentine lake, naturalising woods, designing a cascade and placing clumps in strategic positions. - Stowe - Buckinghamshire Stowe was created by a family once so powerful they were richer than the king. The scale, grandeur and beauty of Stowe is shown through over forty temples and monuments, gracing an inspiring backdrop of lakes and valleys with an endless variety of walks and trails. In the 1741, Lancelot “Capability” Brown was appointed head gardener. He worked with Kent until the latter's death in 1748 and his own departure in 1751. - Audley End House - Essex Once amongst the largest and most opulent in Jacobean England, today Audley End House is set in a tranquil landscape with stunning views across the unspoilt Essex countryside. -

A Guide to Walking in North West Wiltshire

TRADE PROGRAMME Based on one of the first Great Roads commissioned by the Kings of England, the Great West Way® winds its way through landscapes filled with the world-famous and the yet-to-be-discovered. ParticularlyFIT/self-drive suitable tours for WALKING IN NORTH WEST WILTSHIRE Enable your customers discover some of England’s prettiest villages and little towns on a walking break among the glorious mellow landscapes of North West Wiltshire. Cheltenham BLENHEIM PALACE GREAT WEST WAY Oxford C otswolds ns ROUTE MAP ter hil C e Th Clivedon Clifton Marlow Big Ben Suspension Westonbirt Malmesbury Windsor Paddington Bridge Swindon Castle Henley Castle LONDON Combe Lambourne on Thames wns Eton Dyrham ex Do ess College BRISTOL Park Chippenham W rth Windsor Calne Avebury No Legoland Marlborough Hungerford Reading KEW Brunel’s SS Great Britain Heathrow GARDENS Corsham Bowood Runnymede Ascot Richmond Lacock Racecourse Bristol BATH Newbury ROMAN Devizes Pewsey BATHS Bradford Highclere Cheddar Gorge on Avon Trowbridge Castle GREAT WEST WAY Ilford Manor Gardens Westbury STONEHENGE GWR DISCOVERER PASS & AVEBURY Longleat WORLD HERITAGE SITE Journey along the Great West Way on Stourhead Salisbury the bus and rail network using the Great West Way GWR Discoverer pass. Includes PLACES OF INTEREST IN INSIDER unlimited Off-Peak train travel from London Paddington to Bristol via Reading with Feast on fine British cuisine NORTH WEST WILTSHIRE SUGGESTIONS options to branch off to Oxford, Kemble at the Queens Head and Corsham Court Kennet & Avon Enjoy traditional English tea and Salisbury via Westbury (or London The Peppermill Lacock Abbey Canal at Lacock Stables Café and Waterloo to Salisbury with South Western and Fox Talbot Devizes Wharf Courtyard Tea-room, and Overnight in Chippenham Railway). -

A Guide to English Landscapes

Based on one of the first Great Roads commissioned by the Kings of England, the Great West Way winds its way through landscapes filled with the world-famous and the yet-to-be-discovered. GUIDE TO ENGLISH LANDSCAPES Get an insight into an English art form on a 3-day self-drive tour of the Great West Way visiting several genius landscapes created by some of the country’s greatest outdoor architects Cheltenham BLENHEIM PALACE GREAT WEST WAY Oxford C otswolds ROUTE MAP ns ter hil C e Th Clivedon Clifton Marlow Big Ben Suspension Westonbirt Malmesbury Windsor Paddington Bridge Swindon Castle Henley Castle LONDON Combe Lambourne on Thames wns Eton Dyrham ex Do ess College BRISTOL Park Chippenham W rth Windsor Calne Avebury No Legoland Marlborough Hungerford Reading KEW Brunel’s SS Great Britain Heathrow GARDENS Corsham Bowood Runnymede Ascot Richmond Lacock Racecourse Bristol BATH Newbury ROMAN Devizes Pewsey BATHS Bradford Highclere Cheddar Gorge on Avon Trowbridge Castle Ilford Manor Gardens Westbury STONEHENGE & AVEBURY Longleat WORLD HERITAGE SITE Stourhead Salisbury EXAMPLE OF GREAT ENGLISH LANDSCAPES IN THIS AREA PLACES TO EAT PLACES TO STAY Bowood House Great Chalfield Manor Bowood’s Treehouse Cafe Beechfield House Hotel Dyrham Park Lacock Abbey The Flemish Weaver Guyers House Hotel Corsham Court Dyrham Park tearoom The Crown GreatWestWay.co.uk DAY ONE DAY TWO BOWOOD HOUSE & GARDENS CORSHAM You’ll be wowed by Corsham Town to the north west. It’s another of the Great West Way’s glorious timewarp places. Make for Corsham Court whose grounds were largely devised by ‘Capability’ Brown and then extended by Humphry Repton, another Corsham Court acclaimed landscape architect who is often regarded as the successor to Brown. -

University Microfilms 300 North Zaeb Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Corsham Court

www.bathspa.ac.uk B a t h S p a University Studying at Bath Spa University Choose which course to study Corsham Court Centre Find out what it’s like to live in From Design to Creative Corsham/Wiltshire/SN13 0BZ the beautiful city of Bath and Writing – a full guide to all Postgraduate Newton Park Campus study at our environmentally of our courses to help you Newton St Loe/Bath/BA2 9BN award winning campuses choose the right subject for Sion Hill Campus where high quality teaching you and your future career. Prospectus Lansdown/Bath/BA1 5SF and research are priorities. 2012 Tel +44 (0)1225 875 875 Bath Spa University Introduction www.bathspa.ac.uk C o n t e n ts Welcome 02 School of Art and Design 16 School of Education 28 School of Humanities School of Science Reasons to choose Curatorial Practice 18 Initial Teacher Education (PGCE) 30 and Cultural Industries 40 Society and Management 56 Bath Spa University 03 Design 19 Lifelong Learning 31 Creative Writing 41 Business and Management 58 Why Bath Spa University? 04 Design: Brand Development 20 Professional Practice Feature Filmmaking 42 Biology: Graduate Certificate Bath–A World Heritage Design: Ceramics 21 in Higher Education 32 Heritage Management 43 City 90 minutes from London 07 and Diploma 60 Design: Fashion and Textiles 22 Professional Master’s Programme 34 Literature and Landscape 44 The campuses: Corsham Geography: Graduate Certificate Design: Investigation Fashion Design 23 Counselling and Scriptwriting 45 and Diploma 61 Court, Newton Park and Sion Hill 08 Psychotherapy Practice -

The Ashbury Plot 116 Park Place

The Ashbury Plot 116 Park Place Corsham The Ashbury Plot 116 Park Place Corsham SN13 9LA A delightful detached family home with five bedrooms, two reception rooms, utility room and double garage. • Brand New Home • Detached • Five bedrooms • Two Reception Rooms • Kitchen/Family Room • Bathroom & Two En-suites • Double Garage & Parking • • Asking Price £625,000 Description Situation Park Place is but a stone's throw from the quintessential historic market town of Corsham, with its historic high street character buildings and yet providing a full range of everyday facilities, including a wide range of shops, pubs, restaurants etc. It is home to the heritage of Corsham Court, an English country house in a park designed by Capability Brown, notable for its spectacular gardens and fine art collection. Situated just on the fringe of the scenic Cotswolds, Corsham offers a range of countryside pursuits right on your doorstep with the Corsham lakes nearby providing a number of local walks. It is rightly highly regarded for its primary and secondary schools and of course there are plenty of sporting, social and cultural activities to suit all needs and tastes. Corsham is just 10 miles by car from bath and 5 miles to the M4 motorway network at Chippenham, which also has its direct rail connection to Reading and London, which, with the arrival of Crossrail, will make the journey to London, whether for work or pleasure, quick and efficient. Directions From our Corsham office turn right onto Pickwick Road and continue over the next two roundabouts. At the next roundabout turn left onto the A4 and left again at the next roundabout into Park Lane. -

98963783.Pdf

10,000 FAMOUS FREEMASONS B y WILLIAM R. DENSLOW Volume III K - P Foreword by HARRY S. TRUMAN, P.G.M. Past Master, Missouri Lodge of Research Published by Macoy Publishing & Masonic Supply Co., Inc. Richmond, Virginia Copyright, I957, William R. Denslow K Carl Kaas Norwegian lawyer and grand master of the Grand Lodge of Norway since 1957. b. in 1884. He played an important part in securing the return of the many valuable articles and library belonging to the grand lodge which had been removed by the Germans during WWII. Harry G. Kable (1880-1952) President of Kable Bros. 1931-49. b. July 15, 1880 in Lanark, Ill. He was with the Mount Morris News and Gospel Messenger, Mount Morris, Ill. from 1896-98. In 1898 with his twin brother, Harvey J., purchased the Mount Morris Index. Since 1905 it has specialized in the printing of periodicals and magazines. Member of Samuel H. Davis Lodge No. 96, Mt. Morris, Ill. 32° AASR (NJ) and Shriner. d. July 2, 1952. Howard W. Kacy President of Acacia Mutual Life Ins. Co. b. Sept. 19, 1899 in Huntington, Ind. Graduate of U. of Indiana. Admitted to the bar in 1921. He has been with Acacia Mutual since 1923, successively as counsel, general counsel, vice president, 1st vice president, executive vice president, and president since 1955. Director since 1935. Mason and member of DeMolay Legion of Honor. Benjamin B. Kahane Motion picture executive. b. in Chicago in 1891. Graduate of Chicago Kent Coll. of Law in 1912, and practiced in Ill. until 1919. -

FRIENDS of LYDIARD TREGOZ Report No. 34

ISSN: 0308-6232 FRIENDS OF LYDIARD TREGOZ CONTENTS 3 An Elizabethan Girdle Book: An unnoticed feature of the portrait of Lucy Hungerford at Lydiard Tregoze Janet Backhouse 6 The Battle of Ellandun and Lydiard Tregoze Tony Spicer 11 Giles Daubeney (1796-1877), the Cricketing Rector of Lydiard Tregoze Joe Gardner 16 Memories of Shaw, 199-1919 IreneJay 26 Elliot G. Woolford, labourer and farmer, and the House of Bolingbroke Douglas J. Payne 34 The Decline and Fall of the St Johns of Lydiard Tregoze Brian Carne 56 Corrigenda inReport 56 Shorter Notes: New Member of the Committee ‘Thank-you’s and Presentations 57 Swindon Borough Council Newsletter Sarah Finch-Crisp 58 The Friends of Lydiard Tregoz Officers, Membership, and Accounts Report no. 34 The FRIENDS OF LYDIARD TREGOZ was formed in 1967 with the approval and full support of St.Mary’s Church and the Borough of Swindon. The objects of the society are to: - foster interest in the Church, the House, and the Parish as a whole. - hold one meeting in the House annually, usually in mid-May, with a guest speaker. The meeting is followed by tea in the dining room and Evensong in the Parish Church. (The meeting in 1997 was held at Battersea.) - produce annually Report, a magazine of articles which are concerned in the broadest way with the history of the parish, its buildings and people, the St.John family and their antecedents as well as more locally-based families, and the early years of the Sir Walter St.John School in Battersea. Copies of Report are deposited with libraries and institutions in England, Wales, and the United States of America.