How to Avoid Solipsism While Remaining an Idealist: Lessons from Berkeley and Dharmakīrti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leibniz, Bayle and the Controversy on Sudden Change Markku Roinila (In: Giovanni Scarafile & Leah Gruenpeter Gold (Ed.), Paradoxes of Conflicts, Springer 2016)

Leibniz, Bayle and the Controversy on Sudden Change Markku Roinila (In: Giovanni Scarafile & Leah Gruenpeter Gold (ed.), Paradoxes of Conflicts, Springer 2016) Leibniz’s metaphysical views were not known to most of his correspondents, let alone to the larger public, until 1695 when he published an article in Journal des savants, titled in English “A New System of the Nature and Communication of Substances, and of the Union of the Soul and Body” (henceforth New System).1 The article raised quite a stir. Perhaps the most interesting and cunning critique of Leibniz’s views was provided by a French refugee in Rotterdam, Pierre Bayle (1647−1706) who is most famous for his Dictionnaire Historique et Critique (1697). The fascinating controversy on Leibniz’s idea of pre-established harmony and a number of other topics lasted for five years and ended only when Bayle died. In this paper I will give an overview of the communication, discuss in detail a central topic concerning spontaneity or a sudden change in the soul, and compare the views presented in the communication to Leibniz’s reflections in his partly concurrent New Essays on Human Understanding (1704) (henceforth NE). I will also reflect on whether the controversy could have ended in agreement if it would have continued longer. The New System Let us begin with the article that started the controversy, the New System. The article starts with Leibniz’s objection to the Cartesian doctrine of extension as a basic way of explaining motion. Instead, one should adopt a doctrine of force which belongs to the sphere of metaphysics (GP IV 478). -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Mind Body Problem and Brandom's Analytic Pragmatism

The Mind-Body Problem and Brandom’s Analytic Pragmatism François-Igor Pris [email protected] Erfurt University (Nordhäuserstraße 63, 99089 Erfurt, Germany) Abstract. I propose to solve the hard problem in the philosophy of mind by means of Brandom‟s notion of the pragmatically mediated semantic relation. The explanatory gap between a phenomenal concept and the corresponding theoretical concept is a gap in the pragmatically mediated semantic relation between them. It is closed if we do not neglect the pragmatics. 1 Introduction In the second section, I will formulate the hard problem. In the third section, I will describe a pragmatic approach to the problem and propose to replace the classical non-normative physicalism/naturalism with a normative physicalism/naturalism of Wittgensteinian language games. In subsection 3.1, I will give a definition of a normative naturalism. In subsection 3.2, I will make some suggestions concerning an analytic interpretation of the second philosophy of Wittgenstein. In the fourth section, I will propose a solution to the hard problem within Brandom‟s analytic pragmatism by using the notion of the pragmatically mediated semantic relation. In the fifth section, I will make some suggestions about possible combinatorics related to pragmatically mediated semantic relations. In the sixth section, I will consider pragmatic and discursive versions of the mind-body identity M=B. In the last section, I will conclude that the explanatory gap is a gap in a pragmatically mediated semantic relation between B and M. It is closed if we do not neglect pragmatics. 2 The Hard Problem The hard problem in the philosophy of mind can be formulated as follows. -

KNOWLEDGE ACCORDING to IDEALISM Idealism As a Philosophy

KNOWLEDGE ACCORDING TO IDEALISM Idealism as a philosophy had its greatest impact during the nineteenth century. It is a philosophical approach that has as its central tenet that ideas are the only true reality, the only thing worth knowing. In a search for truth, beauty, and justice that is enduring and everlasting; the focus is on conscious reasoning in the mind. The main tenant of idealism is that ideas and knowledge are the truest reality. Many things in the world change, but ideas and knowledge are enduring. Idealism was often referred to as “idea-ism”. Idealists believe that ideas can change lives. The most important part of a person is the mind. It is to be nourished and developed. Etymologically Its origin is: from Greek idea “form, shape” from weid- also the origin of the “his” in his-tor “wise, learned” underlying English “history.” In Latin this root became videre “to see” and related words. It is the same root in Sanskrit veda “knowledge as in the Rig-Veda. The stem entered Germanic as witan “know,” seen in Modern German wissen “to know” and in English “wisdom” and “twit,” a shortened form of Middle English atwite derived from æt “at” +witen “reproach.” In short Idealism is a philosophical position which adheres to the view that nothing exists except as it is an idea in the mind of man or the mind of God. The idealist believes that the universe has intelligence and a will; that all material things are explainable in terms of a mind standing behind them. PHILOSOPHICAL RATIONALE OF IDEALISM a) The Universe (Ontology or Metaphysics) To the idealist, the nature of the universe is mind; it is an idea. -

A Cardinal Sin: the Infinite in Spinoza's Philosophy

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Philosophy Honors Projects Philosophy Department Spring 2014 A Cardinal Sin: The nfinitI e in Spinoza's Philosophy Samuel H. Eklund Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/phil_honors Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Eklund, Samuel H., "A Cardinal Sin: The nfinitI e in Spinoza's Philosophy" (2014). Philosophy Honors Projects. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/phil_honors/7 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Cardinal Sin: The Infinite in Spinoza’s Philosophy By: Samuel Eklund Macalester College Philosophy Department Honors Advisor: Geoffrey Gorham Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without my advisor, Professor Geoffrey Gorham. Through a collaborative summer research grant, I was able to work with him in improving a vague idea about writing on Spinoza’s views on existence and time into a concrete analysis of Spinoza and infinity. Without his help during the summer and feedback during the past academic year, my views on Spinoza wouldn’t have been as developed as they currently are. Additionally, I would like to acknowledge the hard work done by the other two members of my honors committee: Professor Janet Folina and Professor Andrew Beveridge. Their questions during the oral defense and written feedback were incredibly helpful in producing the final draft of this project. -

Descartes' Influence in Shaping the Modern World-View

R ené Descartes (1596-1650) is generally regarded as the “father of modern philosophy.” He stands as one of the most important figures in Western intellectual history. His work in mathematics and his writings on science proved to be foundational for further development in these fields. Our understanding of “scientific method” can be traced back to the work of Francis Bacon and to Descartes’ Discourse on Method. His groundbreaking approach to philosophy in his Meditations on First Philosophy determine the course of subsequent philosophy. The very problems with which much of modern philosophy has been primarily concerned arise only as a consequence of Descartes’thought. Descartes’ philosophy must be understood in the context of his times. The Medieval world was in the process of disintegration. The authoritarianism that had dominated the Medieval period was called into question by the rise of the Protestant revolt and advances in the development of science. Martin Luther’s emphasis that salvation was a matter of “faith” and not “works” undermined papal authority in asserting that each individual has a channel to God. The Copernican revolution undermined the authority of the Catholic Church in directly contradicting the established church doctrine of a geocentric universe. The rise of the sciences directly challenged the Church and seemed to put science and religion in opposition. A mathematician and scientist as well as a devout Catholic, Descartes was concerned primarily with establishing certain foundations for science and philosophy, and yet also with bridging the gap between the “new science” and religion. Descartes’ Influence in Shaping the Modern World-View 1) Descartes’ disbelief in authoritarianism: Descartes’ belief that all individuals possess the “natural light of reason,” the belief that each individual has the capacity for the discovery of truth, undermined Roman Catholic authoritarianism. -

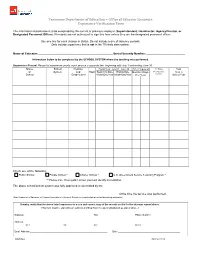

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Brains and Behavior Hilary Putnam

2 Brains and Behavior Hilary Putnam Once upon a time there was a tough- ism appeared to exhaust the alternatives. minded philosopher who said, 'What is all Compromises were attempted ('double this talk about "minds", "ideas", and "sen- aspect' theories), but they never won sations"? Really-and I mean really in the many converts and practically no one real world-there is nothing to these so- found them intelligible. Then, in the mid- called "mental" events and entities but 1930s, a seeming third possibility was dis- certain processes in our all-too-material covered. This third possibility has been heads.' called logical behaviorism. To state the And once upon a time there was a nature of this third possibility briefly, it is philosopher who retorted, 'What a master- necessary to recall the treatment of the piece of confusion! Even if, say, pain were natural numbers (i.e. zero, one, two, perfectly correlated with any particular three ... ) in modern logic. Numbers are event in my brain (which I doubt) that identified with sets, in various ways, de- event would obviously have certain prop- pending on which authority one follows. erties-say, a certain numerical intensity For instance, Whitehead and Russell iden- measured in volts-which it would be tified zero with the set of all empty sets, senseless to ascribe to the feeling of pain. one with the set of all one-membered sets, Thus, it is two things that are correlated, two with the set of all two-membered not one-and to call two things one thing sets, three with the set of all three-mem- is worse than being mistaken; it is utter bered sets, and so on. -

PHI 110 Lecture 2 1 Welcome to Our Second Lecture on Personhood and Identity

PHI 110 Lecture 2 1 Welcome to our second lecture on personhood and identity. We’re going to begin today what will be two lectures on Rene Descartes’ thoughts on this subject. The position that is attributed to him is known as mind/body dualism. Sometimes it’s simply called the dualism for short. We need to be careful, however, because the word dualism covers a number of different philosophical positions, not always dualisms of mind and body. In other words, there are other forms of dualism that historically have been expressed. And so I will refer to his position as mind/body dualism or as Cartesian dualism as it’s sometimes also called. I said last time that Descartes is not going to talk primarily about persons. He’s going to talk about minds as opposed to bodies. But I think that as we start getting into his view, you will see where his notion of personhood arises. Clearly, Descartes is going to identify the person, the self, with the mind as opposed to with the body. This is something that I hoped you picked up in your reading and certainly that you will pick up once you read the material again after the lecture. Since I’ve already introduced Descartes’ position, let’s define it and then I’ll say a few things about Descartes himself to give you a little bit of a sense of the man and of his times. The position mind/body that’s known as mind/body dualism is defined as follows: It’s the view that the body is a physical substance — a machine, if you will — while the mind is a non-physical thinking entity which inhabits the body and is responsible for its voluntary movements. -

Is Plato a Perfect Idealist?

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 3, Ver. V (Mar. 2014), PP 22-25 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Is Plato a Perfect Idealist? Dr. Shanjendu Nath M. A., M. Phil., Ph.D. Associate Professor Rabindrasadan Girls’ College, Karimganj, Assam, India. Abstract: Idealism is a philosophy that emphasizes on mind. According to this theory, mind is primary and objective world is nothing but an idea of our mind. Thus this theory believes that the primary thing that exists is spiritual and material world is secondary. This theory effectively begins with the thought of Greek philosopher Plato. But it is Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) who used the term ‘idealism’ when he referred Plato in his philosophy. Plato in his book ‘The Republic’ very clearly stated many aspects of thought and all these he discussed from the idealistic point of view. According to Plato, objective world is not a real world. It is the world of Ideas which is real. This world of Ideas is imperishable, immutable and eternal. These ideas do not exist in our mind or in the mind of God but exist by itself and independent of any mind. He also said that among the Ideas, the Idea of Good is the supreme Idea. These eternal ideas are not perceived by our sense organs but by our rational self. Thus Plato believes the existence of two worlds – material world and the world of Ideas. In this article I shall try to explore Plato’s idealism, its origin, locus etc. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it.