January 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cloudburstcloudburst

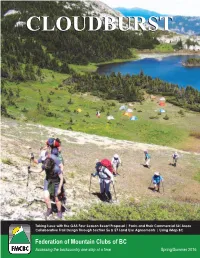

CLOUDBURSTCLOUDBURST Taking Issue with the GAS Four Season Resort Proposal | Parks and their Commercial Ski Areas Collaborative Trail Design Through Section 56 & 57 Land Use Agreements | Using iMap BC Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC Accessing the backcountry one step at a time Spring/Summer 2016 CLOUDBURST Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC Published by : Working on your behalf Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC PO Box 19673, Vancouver, BC, V5T 4E7 The Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC (FMCBC) is a democratic, grassroots organization In this Issue dedicated to protecting and maintaining access to quality non-motorized backcountry rec- reation in British Columbia’s mountains and wilderness areas. As our name indicates we are President’s Message………………….....……... 3 a federation of outdoor clubs with a membership of approximately 5000 people from 34 Recreation & Conservation.……………...…… 4 clubs across BC. Our membership is comprised of a diverse group of non-motorized back- Member Club Grant News …………...………. 11 country recreationists including hikers, rock climbers, mountaineers, trail runners, kayakers, Mountain Matters ………………………..…….. 12 mountain bikers, backcountry skiers and snowshoers. As an organization, we believe that Club Trips and Activities ………………..…….. 15 the enjoyment of these pursuits in an unspoiled environment is a vital component to the Club Ramblings………….………………..……..20 quality of life for British Columbians and by acting under the policy of “talk, understand and Some Good Reads ……………….…………... 22 persuade” we advocate for these interests. Garibaldi 2020…... ……………….…………... 27 Membership in the FMCBC is open to any club or individual who supports our vision, mission Executive President: Bob St. John and purpose as outlined below and includes benefits such as a subscription to our semi- Vice President: Dave Wharton annual newsletter Cloudburst, monthly updates through our FMCBC E-News, and access to Secretary: Mack Skinner Third-Party Liability insurance. -

The Use of Alpine Habitats by Migratory Birds in B.C. Parks 1998 Summary

The Use of Alpine Habitats by Migratory Birds in B.C. Parks 1998 Summary Dr. Kathy Martin Centre for Applied Conservation Biology University of British Columbia Forest Sciences Centre University of British Columbia 2424 Main Mall Vancouver, B.C. V6T 1Z4 phone: (604) 822-9695 fax: (604) 822-9102 email: [email protected] Report compiled by: Steve Ogle Cite as: Martin, K. and S. Ogle. 2000. The Use of Alpine Habitats by Migratory Birds in B.C. Parks: 1998 Summary. Unpublished report, Department of Forest Sciences, Univ. of British Columbia and Canadian Wildlife Service, Pacific and Yukon Region. 15 p. http://www.forestry.ubc.ca/alpine/docs/alpmig-2.pdf Background and objectives Our investigation is aimed at determining the relative importance of high-elevation habitats to migratory birds in southwestern British Columbia. Both altitudinal (moving upslope) and latitudinal (traveling south) migrant birds are thought to take advantage of abundant resources that occur in alpine habitats during late summer. This seasonal resource may play a significant role in the survival of many individuals of various species. Although many high-elevation habitats are protected in parks and reserves, climatologists believe that these areas could be adversely influenced by even minor climatic changes. In southwestern B.C., alpine areas form the headwaters of all major watersheds, and monitoring of avian abundance may help to model the health of downstream water resources. In general, little is known about the ecology of alpine and sub-alpine habitats and we hope that this study will broaden the understanding and awareness of these fragile ecosystems. -

Stanley Park Ecological Action Plan

Date: January 10, 2011 TO: Board Members – Vancouver Park Board FROM: General Manager – Parks and Recreation SUBJECT: Stanley Park Ecological Action Plan RECOMMENDATION A. That the Board approve the recommended actions identified in this report and summarized in Appendix E to improve the ecological integrity of Stanley Park in the following five priority areas of concern: Beaver Lake’s rapid infilling; Lost Lagoon’s water quality; invasive plant species; fragmentation of habitat; and Species of Significance. B. That the Board approve a consultancy to develop a vision and implementation strategy for Beaver Lake in 2011 to ensure the lake’s long-term viability, to be funded from the 2011 Capital Budget. POLICY The Park Board’s Strategic Plan 2005 – 2010 includes five strategic directions, one of which is Greening the Park Board. The plan states that that the “preservation and enhancement of the natural environment is a core responsibility of the Park Board" and that the Board “will develop sustainable policies and practices that achieve environmental objectives while meeting the needs of the community”. It includes actions relevant to the ecological integrity of Stanley Park, such as: advocate for a healthy urban environment, integrate sustainability concepts into the design, construction and maintenance of parks, preserve existing native habitat and vegetation and promote and improve natural environments. The Stanley Park Forest Management Plan, approved on June 15, 2009, includes relevant Goals and Management Emphasis Areas. It identifies Wildlife Emphasis Areas, areas of the forest as having high importance to the ecological integrity of the park, and recommends facilitating projects that protect or enhance wildlife and their habitats. -

Summer/Fall 2018 • Issue 385

Summer/Fall 2018 • Issue 385 PipelineBritish Columbia Council Super Cookie Challenge Ideas New! BC Crest Contest Sisterhood of Guiding It’s time for a new provincial crest! Three members, three viewpoints 2019 Sponsored Travel Events Editorial BC Council Contact Table of Contents and Information Editor’s Note PC’s Page ................................................3 107-252 Esplanade W. Greetings from the editorial team. We took North Vancouver, BC V7M 0E9 Upcoming Events ....................................4 advantage of being in Vancouver at the same Phone: Membership/Events/ time, in May for the BC Council AGM, to Letter to the Editor ...................................5 General Information 604-714-6636 meet in person, some of us for the first time. It’s always nice to put faces to names, and Fax: 604-714-6645 PR Grants for Districts and Areas ..........5 Pipeline’s readers may like to do the same PC Office: 604-714-6643 with this photo of the editorial team. E-mail: [email protected] BC’s 2018 Bursary, Grant and Scholarship Recipients ...................... 6–8 Check out the BC Guiding website at BC Crest Contest ....................................9 www.bc-girlguides.org Send your comments to 2019 Sponsored Travel Events .......10 –11 [email protected] Sisterhood of Guiding .....................12–13 E-mail addresses: [email protected] Alberta Girls’ Parliament 2018 ........14–16 [email protected] Gone Home ...........................................16 Left to right: Katrina Petrik, Robyn So, Linda Hodgkin, [email protected] (Safe Guide) Ruth Seabloom, Ming Berka. Not pictured: Helen [email protected] Varga and Pipeline’s designer, Patti Zazulak. Awards ................................................... 17 [email protected] Our team welcomes new members, whether [email protected] Super Cookie Challenge ............... -

A B C D ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 255 See also separate subindexes for: 5 EATING P000P259 6 DRINKING & NIGHTLIFE P000P260 3 ENTERTAINMENT P261P000 7 SHOPPING P261P000 4 2 SPORTS SLEEPING & ACTIVITIESP000 P262 Index 4 SLEEPING P262 Sunset Beach 70, 42-3 Burrard Bridge 66 Commercial Drive 47, a Third Beach 54 bus travel 245 117-30, 117, 276 Abbott & Cordova 241 Wreck Beach 167-8 business hours 251 drinking & nightlife accommodations 15, Beacon Hill Park (Victoria) Butchart Gardens (Victoria) 118, 122-5 209-20, see also 189 189, 192 entertainment 126-8 individual neighborhoods Beaty Biodiversity Museum food 118, 119-22 activities 20-4, 40-1, see 167 highlights 117-18 also Sports & Activities beer 10, 232, see also c shopping 118, 128-30 subindex, individual Canada Place 57 breweries sights 119 activities Capilano River Hatchery 180 bicycle travel, see cycling sports & activities air travel 244 Capilano Suspension Bridge airports 244 Bill Reid Gallery of 130 n orthwest Coast Art 57 12, 179, 12, 78 accommodations 211 transportation 118 bird watching 150 car travel 245, 247 Amantea, Gisele 133 walks 123, 123 Bloedel Conservatory 148, Carr, Emily 53, 240 ambulance 250 18 Contemporary Art Gallery boat travel 246, see also Carts of Darkness 222 animals 150 58 ferries Catriona Jeffries 134 apples 174 costs 14, 210, 249-52 books 222, 231 cell phones 14, 252 Aquabus 107 Craigdarroch Castle bookstores 39, see also Ceperley Meadows 53-4 (Victoria) 189 aquariums 10, 53 Shopping subindex chemists 251 credit cards 251 Arden, Roy 55 breweries 13, 125, -

IND EX Abbotsford International Air Show 15 Accommodations 189-200

© Lonely Planet Publications INDEX helicopters 223 in Vancouver 226-7 children, travel with 228 See also separate to/from airport 224 to/from Vancouver 224 activities 180 indexes for: Alcan Dragon Boat Festival books, see also literature, arts 170 Arts p248 14 Shopping subindex attractions 88 Drinking p248 ambulance 230 cookbooks 135 Vancouver International Eating p249 antiques, see Shopping environment 58 Children’s Festival 13 Nightlife p250 subindex history 22 Chinatown 76-9, 77, 5 Shopping p250 aquariums 52, 53 local authors 30 food 135-6, 5 INDEX Sights p251 architecture 33-5 Bowen Island 217-18 Night Market 115, 5 Sleeping p252 area codes, see inside front breweries, see Sights shopping 115-16 Sports & cover subindex walking tour 78-9, 78 bridges 35, see also Sights Activities p253 art galleries, see Shopping Chinese New Year 12 subindex Top Picks p253 & Sights subindexes choral music 171-2, see also arts 26-33, see also Arts Buddhist temple 106 Arts subindex Buntzen Lake 216-17 subindex, cinema, dance, Choy, Wayson 29 bus travel A literature, music, theater, Christ Church Cathedral 47 tours 233 Abbotsford International TV, visual arts Christmas Carolship in Vancouver 226 Air Show 15 courses 229 Parade 17 to/from Vancouver 224-5 accommodations 189-200, cinema 31-2, see also film ATMs 232 business hours 228, see also see also Sleeping subindex City Farm Boy 61 inside front cover airport hotels 199 Clark, Rob 130 B bars 148 B&Bs 190 classical music 28, 166-7, B&Bs 190, see also Sleeping coffeehouses 148 costs 191 see also Arts subindex -

NEWLY CLASSIFIED OR UPDATED FACILITIES Facilities Classified in 2007

NEWLY CLASSIFIED OR UPDATED FACILITIES Facilities Classified in 2007 Facility No Facility Name Classification / Level City/Province 1508 0713887 BC Ltd. Small Wastewater System SWWS-M Scotch Creek, BC 1588 Alexandria 3A - Alexandria First Nation Small Water System SWS Quesnel, BC 1555 Anacla 12 - Huu-Ay-Aht First Nation Small Water System SWS Bamfield, BC 598 Apex Mountain Resort (1997) Ltd. Wastewater Treatment Facility MWWT I Penticton, BC 1540 Ashcroft First Nation Small Water System SWS Ashcroft, BC 1392 Aurora Estates Small Wastewater System SWWS-M Moyie Lake, BC 1608 Barclay Crescent Wastewater Collection System WWC I , BC 1546 Barnston Island 3 - Katzie First Nation Small Water System SWS Surrey, BC 972 BC Hydro - GMS Generating Station Water Treatment Facility WT II Hudson's Hope, BC 1591 Beddis Water District Small Water System SWS Salt Spring Island, BC 1551 Bendixon Community Small Wastewater System SWWS-L Prince George, BC 1539 Bonaparte 3 - Bonaparte First Nation Small Water System SWS Cache Creek, BC 1635 Bowen Bay Small Water System SWS Bowen Island, BC 1615 Bralorne Small Wastewater System SWWS-M Bralorne, BC 1614 Bralorne Small Water System SWS Bralorne, BC 448 Bridal Falls Travel Centre Small Wastewater System SWWS-M Rosedale, BC 1510 Britannia Mine Water Treatment Facility WT IV Britannia Beach, BC 1616 Buckhorn Community Small Wastewater System SWWS-L Prince George, BC 1611 Bugaboo Lodge Small Wastewater System SWWS-M Invermere, BC 1631 Burrard Inlet 3 - Burrard First Nation Small Water System SWS North Vancouver, -

Land for LEASE

Partnership. Performance. Image Source: Google River Road 1611 Patrick Street 0.912 acres (39,727 SF) Patrick Street Savage Road 1600 Savage Road 1.305 acres (56,846 SF) LAND FOR LEASE Opportunity 1600 SAVAGE ROAD & To lease two properties totalling 1611 PatrICK STREET approximately 2.22 acres of fenced RICHMonD, BC yard area in North Richmond Ryan Kerr*, Principal Angus Thiele, Associate 604.647.5094 604.646.8386 [email protected] [email protected] *Ryan Kerr Personal Real Estate Corporation 1600 SAVAGE ROAD & 1611 PatrICK StrEET RICHMonD, BC Location Property Details The subject properties provide the opportunity to lease up to 2.22 acres of fenced and secured yard space conveniently located off of River Road between Available Land Area Savage Road and Patrick Street, east of No. 6 Road, in north Richmond, BC. This site boasts a central location, with convenient access to Vancouver and the rest 1600 Savage Road 1.305 acres (56,846 SF) of the Lower Mainland via major arterials such as Knight Street, SW Marine Drive, 1611 Patrick Street 0.912 acres (39,727 SF) Highway 91, and Highway 99. Total 2.22 acres (96,573 SF)* Zoning *Approximately I-L (Light Impact Industrial Zone) is intended to accommodate and regulate Lease Rate the development of light impact industry, transportation industry, warehouses, $2.25 PSF Net distribution centres and limited office and service uses. Access Each property has one (1) point of access & Property Features egress • 1600 Savage Road is fenced and paved Available Immediately • 1611 Patrick Street is fenced and compacted gravel • Rare opportunity to lease yard of this size in Richmond Ryan Kerr*, Principal 604.647.5094 DriveD riveTime MapTimes Map [email protected] To Snug Cove To Langdale *Ryan Kerr Personal Real Estate Corporation Cypress Provincial Park ture Bay) par Horseshoe o (De Bay aim Nan To Whytecli HORSESHOE BAY Park Ferry Terminal Whytecli Lynn Headwaters MARINE DR. -

Trees in Metro Vancouver

Trees in The Lower Mainland In 2001, the Botany Section of Nature Vancouver, published a brochure titled Trees in The Lower Mainland. Following is the revised and updated (March, 2018) text of the original brochure. Public arboretums, Urban Forests and Tree walks in Metro Vancouver · Your Invitation to: Visit, Learn, Support and Enjoy · Trees: Grace our Streets, Parks and Gardens · Trees: Sustain Other Living Forms · Trees: Basic in our Economy Arboretums and Botanical Gardens: · Riverview Arboretum, Coquitlam. Guided tours organized by Riverview Horticultural Centre Society, http://rhcs.org · Queen Elizabeth Arboretum. 33rd and Cambie St.,Vancouver. Native and exotic trees. · Stanley Park, Vancouver. Native and exotic trees. Stanley Park Ecological Society, http://www.stanleyparkecology.ca · VanDusen Botanical Garden, 37th and Oak St. Vancouver. http://vandusengarden.org · University of B.C. Botanical Garden, Vancouver. http://botanicalgarden.ubc.ca. · University of B.C. Grounds, Vancouver. S.W. Marine Drive and West Mall Plant Operations · Redwood Park. 20th Ave, between 176 & 180 St., Surrey. Mainly Giant Sequoias. · Cypress Provincial Park, West Vancouver. Subalpine trees. · Park and Tilford Gardens. 440 - 333 Brooksbank Ave, North Vancouver. http://parkandtilford.com · Green Timbers and Forest Arboretum. B.C. Forest Service Reserve, 14255-96th Ave, Surrey. http://www.surrey.ca/culture-recreation/2104.aspx. · Research Station Arboretum, Agassiz. Canada Agriculture, 6947 Highway No. 1. Urban Forests and Tree Walks: · Pacific Spirit Regional Park, Vancouver. · Lower Seymour Demonstration Forest, North Vancouver. · UBC Research Forest, Maple Ridge. · Sunnyside Urban Forest, Surrey. · Stanley Park, Vancouver. · Central Park, Burnaby. · Lighthouse Park, West Vancouver. · Minnekhada Regional Park Coquitlam. · Campbell Valley Regional Park Langley. -

Trailblaze Guide

Contents British Columbia and Yukon..………………………………………………………….……….. Page 2 Vancouver Island…………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 8 Northern Alberta…………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 13 Southern Alberta…………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 15 Saskatchewan……………………………………………………………………..………………….. Page 19 Manitoba……………………………………………………………………..…………………….…… Page 21 Eastern Ontario……………………………………………………………………..………..……… Page 23 Toronto and Central Ontario…………………………………………………………………… Page 25 Southwestern Ontario…………………………………………………………………………..… Page 30 Quebec……………………………………………………………………..………………………..….. Page 33 New Brunswick……..……………………………………………………………..…………….….. Page 35 Nova Scotia……………….......……………………………………………………..…………..…... Page 37 Prince Edward Island..……………………………………………………..……………….…….. Page 39 Newfoundland and Labrador...………..……………………………………..……………….. Page 42 1 WWW.TRAILBLAZEFORWISHES.CA BRITISH COLUMBIA & YUKON Stanley Park Seawall Trail Region: Lower Mainland Location: Vancouver Length: 9.3 KM Website: https://www.alltrails.co m/trail/canada/british- columbia/stanley-park- seawall-trail Photo from:https://www.alltrails.com/trail/canada/british-columbia/stanley- park- seawall-trail Dog Mountain Trail - Mount Seymour Provincial Park Region: Lower Mainland Location: North Vancouver Length: 5.6 KM Website: https://www.alltrails.com/trail/ca nada/british-columbia/dog- mountain-trail Photo from: https://www.vancouvertrails.com/trails/dog-mountain/ 2 WWW.TRAILBLAZEFORWISHES.CA West Dyke Trail & Garry Point Park Region: Lower Mainland Location: Richmond Length: -

Lower Fraser Valley Streams Strategic Review

Lower Fraser Valley Streams Strategic Review Lower Fraser Valley Stream Review, Vol. 1 Fraser River Action Plan Habitat and Enhnacement Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada 360 - 555 W. Hastings St. Vancouver, British Columbia V6B 5G3 1999 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Lower Fraser Valley streams strategic review (Lower Fraser Valley stream reveiw : vol. 1) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-662-26167-4 Cat. no. Fs23-323/1-1997E 1. Stream conservation -- British Columbia --Fraser River Watershed. 2. Stream ecology -- British Columbia -- Fraser River Watershed. 3. Pacific salmon fisheries -- British Columbia --Fraser River Watershed. I. Precision Identification Biological Consultants. II. Fraser River Action Plan (Canada) III. Canada. Land Use Planning, Habitat and Enhancement Branch. IV. Series. QH541.5S7L681997 333.91’6216’097113 C97-980399-3 Strategic Review – Preface PREFACE The Lower Fraser Valley Streams Strategic Review provides an overview of the status and management issues on many of the salmon bearing streams in the Lower Fraser Valley. This information has been compiled to assist all concerned with Goals for Sustainable Fisheries managing and protecting this important public resource. Fisheries and Oceans Canada has This includes federal, provincial and local governments, identified seven measurable and achievable goals for sustainable community groups, and individuals. fisheries. These are as follows: While the federal government, specifically Fisheries and 1. Avoid irreversible human induced Oceans Canada, is responsible for managing fish and fish alterations to fish habitat. Alterations to fish habitat that reduce habitat (goals included in sidebar), this important public its capacity to produce fish resource is completely dependent upon land and water to populations which cannot be reversed within a human generation are to be produce and sustain its habitat base. -

COUNCIL REPORT Westvancouver

COUNCIL A GENDA Date: EYI’np ifl( tern: Director DISTRICT OF WEST VANCOUVER 750 17TH STREET, WEST VANCOUVER SC V7V 3T3 COUNCIL REPORT Date: May 25, 2020 —__________________________ From: Stephen Mikicich, Manager, Economic Development I Subject: Update on Economic Development Plan Implementation and Local Economic Recovery File: 2580-1 0-2020 RECOMMENDATION THAT 1. The report dated May 25, 2020 providing an update on Economic Development Plan implementation and local economic recovery be * received for information; and 2. A Council representative be appointed to the Economic Recovery Task Force, as described in Appendix ‘A’ to this report. 1.0 Purpose The purpose of this report is to update Council on the ongoing implementation of the Economic Development Plan and refinements made to the District’s economic development role since July 2019; and to describe District actions to support local businesses during the Provincial government’s COVID-19 response through May 2020, and BC’s Restart Plan over the next 18 months. 2.0 Executive Summary This report provides an update on Economic Development Plan implementation through spring 2020. It also describes District support for local businesses since the declaration of the COVID-1 9 pandemic, and in response to a series of Provincial health orders and the introduction of economic supports by senior levels of government. This report outlines current District efforts to expand outdoor retail space and restaurant seating for local businesses facing reduced sales volumes due to ongoing social distancing requirements under Phase II of the Province’s Restart Plan which began in mid-May 2020. While much remains uncertain during this pandemic, the District must continue its support for local economic recovery and a more resilient community.