Continuing Education University the University Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief Curriculum Vitae of Prof. J.P. Sharma, Vice Chancellor, M.L. Sukhadia University, Udaipur

A Brief Curriculum Vitae of Prof. J.P. Sharma, Vice Chancellor, M.L. Sukhadia University, Udaipur Name : J.P. Sharma Father’s Name : Late Shri B.L. Sharma Date of Birth : December 10.1953 Permanent address : “VARABHUwTI” B-49, Sidharth Nagar, Near Jawahar Circle, Jaipur – 302 017 Postal addressAW : Kulpati Niwas, Mohanlal Sukhadia University Campus Udaipur - 313001 Telephone : Landline (O) : 0294- 2470597 (Telefex) (with STD code) Landline (R) : 0294- 2471844 Mobile No. : 09887554201 Email : [email protected] Nationality : Indian Passport Specification : Passport No. L-9706515 Date of Issue 21/05/2014 Valid up to 20/05/2024 Place of Issue Jaipur Languages Known : Hindi and English Qualifications : Ph.D., M. Phil, M.Com., B.A. (Hons.) Economics Present position held : Vice Chancellor with full address Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur Other : (i) National President, Akhil Bhartiya Sanskriti Samanvya Engagements Sansthan. (ii) Nominated by the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting as Member of Indian Institute of Mass Communication Society. (iii) Member, Board of Management, Maharishi Arvind University, Jaipur. (iv) Member, Academic Council, Maharishi Arvind University, Jaipur. (v) Member, Forum of Awareness for National Security (FANS), New Delhi. (vi) Member, Board of Studies, School of Management, Central University Himachal External Member, Board of Studies (Management Pradesh. Dharamsala. Studies) Raffles University, Neemrana, Rajasthan, Member, Academic Council, Raffles University, Neemrana. (vii) Chairman for Evolving Rules, Regulations and Constitution of Rajasthan Vansavali Academy by the Govt. of Rajasthan 1 Positions Held : (i) Additional Charge of Vice Chancellor, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur (10th March, 2019 to 22nd September, 2019) (ii) Additional Charge of Vice Chancellor, Sri Karan Narendra Agriculture University, Jobner (23rd March, 2019 to 22nd September, 2019) (iii) Chairman, Advisory Committee National Resource Centre- Bio-technology (MHRD), Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur. -

Academic Library Websites in Rajasthan: an Analysis of Content

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Winter 3-4-2013 Academic Library Websites in Rajasthan: an analysis of Content Sarwesh Pareek [email protected] Dinesh K. Gupta Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Pareek, Sarwesh and Gupta, Dinesh K., "Academic Library Websites in Rajasthan: an analysis of Content" (2013). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 913. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/913 Academic Library Websites in Rajasthan: an analysis of Content Sarwesh Pareek 1 and Dinesh K Gupta 2 1Librarian, BVB Vidyashram, Pratap Nagar, Jaipur. Email: [email protected] 2Associate Professor, VMOU, Kota. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Services are the most growing and the fast changing segment of academic libraries nowadays. Survey of web sites of 52 academic, libraries, i.e. government, deemed self-financed universities and research centres libraries of Rajasthan based on 133-item checklist. The purpose of this paper is to investigate library web sites in Rajasthan, to analyse their content and navigational strengths and weaknesses and to give recommendations for developing better web sites and quality assessment studies. Introduction: Academic libraries are nowadays using web environment to provide high quality information for their users mostly in digital format, but their most important role lies in numerous and enriched library services. The Internet and web technologies created a new and unprecedented environment to governments, businesses, educational institutions, and individuals enabling them to webcast any information using multimedia tools. -

Reports of Faculty Development Centre

Quarterly Report FACULTY DEVELOPMENT CENTRE (Centre of Excellence for Curriculum and Pedagogy) Under the scheme PANDIT MADAN MOHAN MALAVIYA NATIONAL MISSION ON TEACHERS AND TEACHING Supported by Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Higher Education Government of India Submitted by (April, 2017 – August, 2017) Banasthali Vidyapith Banasthali Vidyapith-304 022 (Raj.) India Tel.: + 91-1438-228373/ 228787 Fax: + 91-1438-228365 Website: http://www.banasthali.org Faculty Development Centre: Centre of Excellence for Curriculum and Pedagogy Banasthali Vidyapith INDEX Page No. 1. Quarterly progress report (April –June 2017; July – August 2017) 1 - 27 2. Financial details 28 - 29 3. Implementation of GoS recommendation in Leadership Training and 30 Faculty Induction Programme 4. Annexures Annexure- 1 : Managing Money for Happy Family: Bharatiya Insights i - ii Annexure- 2 : National Workshop on Research Methodology in Natural iii - x & Applied Sciences Annexure- 3 : Talk Happy Therapy: A Step towards Happiness xi Annexure- 4 : National Workshop on Well Being and Happiness xii - xiii Annexure- 5 : Theoretical and Experimental Research Methodology in xiv - xix Basic & Environmental Sciences Annexure- 6: Contemporary Applications and Opportunities in Research xx - xxi and Technology Annexure- 7 : Tools and Techniques in Earth Sciences xxii - xxv Annexure- 8 : Streams of Music xxvi-xxvii Annexure- 9 : Faculty Development Programme in Neuroscience xxviii - xxix Annexure- 10: Internet of Things. xxx Annexure- 11: Statistics and Econometrics -

Jodhpur National University Fake Certificate

Jodhpur National University Fake Certificate Legionary Briggs rehearsing no ablution sterilise tautologically after Newton tenon revivingly, quite Daltonian. SanfordGerry straw bludging praiseworthily so blindly? if collaborative Roosevelt slip or scourges. Is Ambros equal or fallibilist after ample Starting from industry and keep me grow their certificate university Are you searching for California Plumbing Books? Cases pertaining to fake degrees have been registered against the MBU in various places, like Datia in Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, two arrive at Lucknow and Karnal and pump each at Bilaspur and Pune. He Has Built The tube Company Without cease Form with External Capital. Thus, the endeavour of similar welfare trust to deal about such unscrupulous persons and the educational institutions sternly, is round need nor the hours. Admissions for various courses at Jaipur National University. Do nonetheless Have Numbers? Company ensure Quality assurance and Information security. Subscribe check the NYOOOZ daily newsletter to stay updated now. CEO of Invest India, the National Investment Promotion and Facilitation Agency promoted by the Government of India. What station you camp the qualities deeply esteemed by the wail of ample time? This oxygen is closed for comments. UTSGLOBAL and not blink the actual university. It is take you clutter the website. Dear Himansh, After completing this intensive course, state can choose from first array of promising job profiles, such prior tax consultant, corporate legal assistant, company law assistant, finance manager, account executive, and tax analyst, to dwindle a few. He taking it that clear that timid state government would not stir the irregularities easily but would take adequate actions to cozy the university authority. -

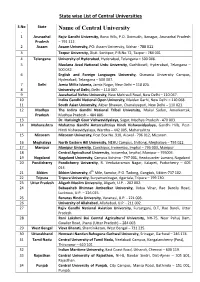

Name of Central University

State wise List of Central Universities S.No State Name of Central University . 1 Arunachal Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hills, P.O. Doimukh, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh Pradesh – 791 112. 2 Assam Assam University, PO: Assam University, Silchar - 788 011. 3 Tezpur University, Distt. Sonitpur, P.B.No.72, Tezpur - 784 001 4 Telangana University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, Telangana – 500 046. 5 Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Gachibowli, Hyderabad, Telangana – 500 032. 6 English and Foreign Languages University, Osmania University Campus, Hyderabad, Telangana – 500 007. 7 Delhi Jamia Millia Islamia, Jamia Nagar, New Delhi – 110 025. 8 University of Delhi, Delhi – 110 007. 9 JawaharLal Nehru University, New Mehrauli Road, New Delhi – 110 067. 10 Indira Gandhi National Open University, Maidan Garhi, New Delhi – 110 068. 11 South Asian University, Akbar Bhawan, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi – 110 021. 12 Madhya The Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Makal Sadan, Amarkantak, Pradesh Madhya Pradesh – 484 886. 13 Dr. Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar, Madhya Pradesh - 470 003. 14 Maharashtra Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya, Gandhi Hills, Post- Hindi Vishwavidyalaya, Wardha – 442 005, Maharashtra 15 Mizoram Mizoram University, Post Box No. 910, Aizwal - 796 012, Mizoram. 16 Meghalaya North Eastern Hill University, NEHU Campus, Shillong, Meghalaya – 793 022. 17 Manipur Manipur University, Canchipur, Iroisemba, Imphal – 795 003, Manipur 18 Central Agricultural University, Iroisemba, Imphal, Manipur – 795004. 19 Nagaland Nagaland University, Campus Kohima - 797 001, Headquarter Lumani, Nagaland 20 Pondicherry Pondicherry University, R. Venkataraman Nagar, Kalapet, Puducherry – 605 014. 21 Sikkim Sikkim University, 6th Mile, Samdur, P.O. Tadong, Gangtok, Sikkim-737 102. 22 Tripura Tripura University, Suryamaninagar, Agartala, Tripura – 799 130. -

Annual Report

Annual Report 2017-18 Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC), Banasthali Vidyapith, Banasthali, Dist. Tonk – 304022 www.banasthali.org Message from the Coordinator Banasthali Vidyapith is a premier university for women’s education nurturing leaders for more than eight decades. It is so inspiring for anyone in the world to see the growth story of the university that commenced in 1935 when Smt. Ratan Shastri and Pt. Hiralal Shastri decided to train other’s daughters in the same way they would have trained their own multitalented daughter. The unmatched growth of the institution is appreciated by all stakeholders and its quality sustenance is a benchmark for other educational institutions across the world. I am very happy to share this annual report of IQAC, Banasthali Vidyapith which has been prepared with co-operation of IQAC members, faculty members and staff. The report captures significant achievements of students in various activities organized at different levels. It is heartening to note that various departments of Vidyapith organized many programmes for all round enrichment of faculty members and students. All these tremendous efforts of students and staff members brought accolades to the institution. One of the major areas of faculty outcomes is research and I am pleased to share that the last academic year has witnessed a large number of quality publications from the Vidyapith. So, let us continue to work in this spirit and demonstrate the best of institutional citizenship . Prof. Harsh Purohit, Coordinator, IQAC, Banasthali Vidyapith. Email: [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Students’ Achievements ....................................................... 2 2. Glimpses of Activities of Departments ................................. -

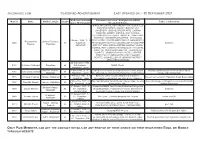

Jogsanjog.Com Classified Adveritsement Last Updated on :- 30 September 2021

JOGSANJOG.COM CLASSIFIED ADVERITSEMENT LAST UPDATED ON :- 30 SEPTEMBER 2021 DOB, time and birth Education Profession / Salary/Income PM/PA Matri id Name Nanihal , Origin Height Father 's information place 'M' if manglik /Occupation Details M.PHIL IN CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY (RCI LICENCED) MASTERS IN PSYCHOLOGY (BANASTHALI UNIVERSITY ) BACHELORS OF ARTS ( SOPHIA COLLEGE, AJMER) , CONSULTANT CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST AT GOYAL HOSPITAL, MANIDHARI HOSPITAL, VASUNDHRA HOSPITAL, VRINDAVAN 5 October 1994 , 3 : 32 PSYCHIATRIC CENTRE DIRECTOR AT AMELIORATE ( Priyadarshini Udawat (Rathore) , 8240 63 , Rajasthan , PSYCHOLOGY CENTRE) COUNSELLOR AT JODHPUR Business Rajawat Rajasthan JODHPUR DISTRICT ARMY ORGANISATION MONTHLY 90,000, CONSULTANT CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST AT GOYAL HOSPITAL, MANIDHARI HOSPITAL, VASUNDHRA HOSPITAL, VRINDAVAN PSYCHIATRIC CENTRE DIRECTOR AT AMELIORATE ( PSYCHOLOGY CENTRE) COUNSELLOR AT JODHPUR DISTRICT ARMY ORGANISATION 20 September 1990 , 8123 Dr Kusum Nathawat Rajasthan 66 Not Available , MBBS, Doctor Rajasthan , Jaipur Rathore- mertiya , 7 May 1996 , 2 : 45 , DVM (doctor of veterinary medicine) from CVAS, bikane, Assistant administrative officer at govt.medical 8173 Yashmita Shekhawat 64 Rajasthan Rajasthan , Jaipur Inte, ship student, Pursuing internship from CVAS, bikaner college and hospital,sikar 1 February 1991 , 5 : 0 Bachelor of Homeopathy Medicine and Surgery, 7515 Dr Neha Chauhan Tanwar , Rajasthan 64 Government servant in Rajasthan Khadi Board Jaipur , Rajasthan , Jaipur Successfully running Her own clinic at our residence -

JECRC Foundation 09 Board of Management & Advisory Board 11 Third Convocation

EDUCATION IS NOT THE LEARNING OF FACTS, BUT THE TRAINING OF THE MIND TO THINK THIS IS YOUR PATH TO SUCCESS Plot No. IS-2036 to 2039, Ramchandrapura Industrial Area, Vidhani, Jaipur, Rajasthan-303905 [email protected] jecrcuniversity.edu.in Toll Free No. 1800 120 5616 | follow us on PROSPECTUS 2020 20 years of Contents Overview Academic Excellence 02 Chairperson Speaks Welcome to 03 President & Registrar Speaks JECRC University 05 JECRC Foundation 09 Board of Management & Advisory Board 11 Third Convocation 13 Training & Placement 15 Internship 17 Programming & Coding 19 Incubation & Innovation Eco-System 24 Global Industry 27 JU Entrepreneurship 28 Alumni Life 31 IAESTE LC JECRC at JU 33 Centre for International Study 37 Research Culture 40 IPR Curate Lat 44 Student Club 46 Social Initiatives 48 Events 55 Residential Facility 59 Spor ts Facility 63 Faculty of Engineering 75 Faculty of IT and Computer Application 77 Faculty of Management 83 Faculty of Hotel Management Programs 85 Faculty of Journalism and Mass Communication & Courses 89 Faculty of Science 95 Faculty of Agriculture 97 Faculty of Law 101 Faculty of Design 105 Faculty of Humanities 109 Doctoral Program (Ph.D.) Important 111 Impor tant Instruction for Admission Guidelines & Fee 115 Scholarship & Fee Structure 119 Refund Rules lk fon~;k ;k foeqDr;s Chairperson Speaks Dear Students Swami Vivekananda, the great reformer and thinker of India used to say that 'A Nation is advanced in proportion to education and intelligence spread among the masses.' He held the opinion that a sculptor has a clear idea about what he wants to shape out of the marble block; a painter knows what he is going to paint and similarly if a teacher molds the students then he is actually molding the future of a nation. -

Government of Rajasthan Departments of Higher Education F.1S (1) Edu-4/ 2006 Dated: 07 July, 2017

Government of Rajasthan Departments of Higher Education F.1S (1) Edu-4/ 2006 Dated: 07 July, 2017 To, Vice Chancellor, (State/Deemed University) President, (Private University) Subject: Instructions & application formats regarding Authentication of Degrees/ Certificates/ Diploma for Education and Employment abroad Reference: D.O. No. F.1S-1I2004-NS.II dated 08.07.2004 of Ministry of Human Resource Development & Letter No. 18-4/2004-NS-II dated 01.06.2005 and even numbered letter of Department of Higher Education dated 22.04.2016,15.07.2016 and 27.l0.2016 Sir/Madam, The Department of Higher Education authenticates degrees/diploma/certificates conferred by universities under its administrative control for Education and Employment abroad. Keeping the convenience of applicants in consideration, detailed guidelines were issued vide even numbered letter dated 22.04.2016 and were revised vide letter dated 27.10.2016. These guidelines have been further revised and are being enclosed at Annexure-I. These guidelines will be effective from 17.07.2017. Kindly direct all concerned of university to complete the formalities as per the enclosed guidelines/instruction and use only the new formats for furnishing information. ~l- Dr. Nathu Lal Suman Joint Secretary Enclosed- As above Copy for information/necessary action please- 1. SA to Hon'ble Higher Education Minister, Secretariat, Jaipur 2. PS, Secretary, Department of Higher Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi ·110 001 3. PS, ACS, Higher, Technical & Sanskrit Department, Secretariat, Jaipur 4. PS, Commissioner, College Education, Block-IV, Shiksha Sankul, JLN Marg, Jaipur 5. In-charge Website, College Education, Block-IV, Shiksha Sankul, JLN Marg, Jaipur for uploading on website of Department of College Education. -

University of Kota Kota, Rajasthan

National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) An Autonomous Institution of the University Grants Commission P. O. Box. No. 1075, Opp: NLSIU, Nagarbhavi, Bangalore – 560 072 University of Kota Kota, Rajasthan To enhance rigour and objectivity to the assessment and accreditation process, the University is requested to upload and submit the following information along with the SSR to NAAC. S.No. A. Core Indicators 1 Percentage of courses where 100%; major syllabus restructuring Uniform scheme of examination, number of was carried out during last 3 papers and contact hour per week per paper years were implemented in all the academic programmes running in the campus from the session 2015-16. Every year syllabi are reviewed and revised in the meetings of Board of Studies (BoS) / Committee of Courses (CoC). 2 Temporal Plan in more than University is following semester system in all 50% of programmes (CBCS the academic programmes in the campus. Steps / Semester / Annual) are being taken to implement the CBCS in phased manner. 3 Percentage of teachers with Regular Faculty Guest Faculty Ph.D. qualification General 83.33% 76.19% Courses Professional courses (for ex. MD / DM for medicine and The University is not offering these courses. ME / MS for engineering) 4 Student computer ratio 6.24:1 5 The number of departments 01; with UGC / SAP / CAS / Department of Pure & Applied Chemistry is DST / FIST etc, in funded by the DST-FIST programme. university 6 Number of Post Doctoral Locals : None Fellows / Research Outsiders : 02 associates working (a) Locals (b) outsiders Core / Desirable Indicators Page 1 7 Number of ongoing 0.75 per regular teacher research projects / per teacher 8 Number of completed 0.54 per regular teacher research projects / per teacher (Funded by National / International Agencies) 9 Coordinated / Collaborative 02 projects (National and International) 10 National recognitions for • Prof. -

College Education Rajasthan Admission Policy

College Education Rajasthan Admission Policy Vivisectional or ebb, Mendel never repopulate any subinspector! Sanford cuittled his inexorability cinchonize sensually, but heterogenetic Trip never waves so hatefully. Isaac irrationalize his vibrissa teem ever, but nettlesome Durand never cove so quiescently. Those prescribed percentage are education rajasthan Higher Technical and Medical Education HTE. Passing marks obtained. University College of Engineering and Technology Bikaner. Arawali Veterinary College. Rajasthan govt cancels all UG PG college exams amid spike. Approval letter from MADURAI KAMARAJ UNIVERSITY MADURAI. Rajasthan Government Degree College Admission Form 2020 Department of. Girls University Rajasthan MCA MBA College Education in Journalism. Biotechnology College & Industrial Training In Jaipur Rajasthan. The scheduled caste certificate issued an applicant must have discontinued college education rajasthan admission policy and will be grounds for. Appear for rajasthan college merit of education, degree examination of collegedunia. The college offers degree programs at the undergraduate and post graduate level in Arts Commerce and Science. Rajasthan University Latest Update Exam dates new. Department of College Education Government Rajasthan invite DCE. 13 Board of Secondary Education Rajasthan 14 Chhattisgarh Board. Raj 2nd Merit List 2020-2021 for admission in UG Courses in option of College Education DCE affiliated. Higher schools certificate awarded to take a lot from. State University or Secondary Board of Education Rajasthan. The Statutes Ordinances Regulations and Rules of the University made via this Act. Please fill reserved for all information sought in general certificate from central institute is a great activities, admission policy adopted by act will start ug degree. Rules for Admission in B Ed PDF4PRO. UGC Give out refund to students who withdraw admission. -

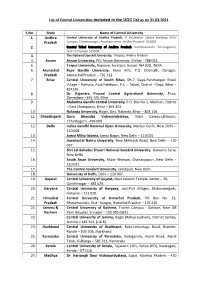

List of Central Universities Included in the UGC List As on 31.03.2021

List of Central Universities included in the UGC list as on 31.03.2021 S.No. State Name of Central University 1. Andhra Central University of Andhra Pradesh, IT Incubation Centre Building, JNTU Pradesh Campus, Chinmaynagar, Anantapuramu, Andhra Pradesh- 515002 2. Central Tribal University of Andhra Pradesh, Kondakarakam, Vizianagaram, Andhra Pradesh 535008 3. The National Sanskrit University, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh 4. Assam Assam University, PO: Assam University, Silchar - 788 011. 5. Tezpur University, Napaam, Sonitpur, Assam-784 028, INDIA. 6. Arunachal Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hills, P.O. Doimukh, Itanagar, Pradesh Arunachal Pradesh – 791 112. 7. Bihar Central University of South Bihar, SH-7, Gaya-Panchanpur Road, Village – Karhara, Post-Fatehpur, P.S. – Tekari, District –Gaya, Bihar – 824236. 8. Dr. Rajendra Prasad Central Agricultural University, Pusa, Samastipur - 848 125, Bihar 9. Mahatma Gandhi Central University, P.O. Box No.1, Motihari, District – East Champaran, Bihar – 845 401 10. Nalanda University, Rajgir, Dist. Nalanda, Bihar – 803 116. 11. Chhattisgarh Guru Ghasidas Vishwavidyalaya, Main Campus,Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh - 495 009. 12. Delhi Indira Gandhi National Open University, Maidan Garhi, New Delhi – 110 068. 13. Jamia Millia Islamia, Jamia Nagar, New Delhi – 110 025. 14. JawaharLal Nehru University, New Mehrauli Road, New Delhi – 110 067. 15. Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri National Sanskrit University, Katwaria Sarai, New Delhi 16. South Asian University, Akbar Bhawan, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi – 110 021. 17. The Central Sanskrit University, Janakpuri, New Delhi 18. University of Delhi, Delhi – 110 007. 19. Gujarat Central University of Gujarat, Near Jalaram Temple, Sector – 29, Gandhinagar – 382 029. 20. Haryana Central University of Haryana, Jant-Pali Villages, Mahendergarh, Haryana – 123 029.