Telling the Nauvoo Story 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Book of Mormon Keystone of My Life!

The Book of Mormon Keystone of my life! ¾ Keystone of Our Religion We all know the Book of Mormon is the keystone of our religion. As the Prophet Joseph Smith stated on the introduction page, “…. I told the brethren that the Book of Mormon was the most correct of any book on the earth, and the keystone of our religion, and a man (or woman) would get nearer to God by abiding by its precepts, than by any other book.” In October Conference 1986, Elder Boyd K. Packer stated, “…true doctrine understood, changes attitudes and behavior. The study of the doctrines of the Gospel will improve behavior quicker than a study of behavior will improve behavior.” ¾ A Remarkable Difference As I have grown in the gospel and also watched my children grow in the gospel I have noticed a remarkable difference as we have studied the Book of Mormon. Any study of Christ and his life will bring you closer to the Lord, but there is a power in the Book of Mormon like no other book. In 1980, when we were young parents Marion G. Romney in his April conference address said, “....I believe that if, in our homes, parents will read from the Book of Mormon prayerfully and regularly, both by themselves and with their children, the spirit of that great book will come to permeate our homes and all who dwell therein. The spirit of reverence will increase; mutual respect and consideration for each other will grow. The spirit of contention will depart. Parents will counsel their children in greater love and wisdom. -

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work PROFESSIONAL TRACK 2009-present Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 2003-2009 Associate Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1997-2003 Assistant Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1994-99 Faculty, Department of Ancient Scripture, BYU Salt Lake Center 1980-97 Department Chair of Home Economics, Jordan School District, Midvale Middle School, Sandy, Utah EDUCATION 1997 Ed.D. Brigham Young University, Educational Leadership, Minor: Church History and Doctrine 1992 M.Ed. Utah State University, Secondary Education, Emphasis: American History 1980 B.S. Brigham Young University, Home Economics Education HONORS 2012 The Harvey B. Black and Susan Easton Black Outstanding Publication Award: Presented in recognition of an outstanding published scholarly article or academic book in Church history, doctrine or related areas for Against the Odds: The Life of George Albert Smith (Covenant Communications, Inc., 2011). 2012 Alice Louise Reynolds Women-in-Scholarship Lecture 2006 Brigham Young University Faculty Women’s Association Teaching Award 2005 Utah State Historical Society’s Best Article Award “Non Utah Historical Quarterly,” for “David O. McKay’s Progressive Educational Ideas and Practices, 1899-1922.” 1998 Kappa Omicron Nu, Alpha Tau Chapter Award of Excellence for research on David O. McKay 1997 The Crystal Communicator Award of Excellence (An International Competition honoring excellence in print media, 2,900 entries in 1997. Two hundred recipients awarded.) Research consultant for David O. McKay: Prophet and Educator Video 1994 Midvale Middle School Applied Science Teacher of the Year 1987 Jordan School District Vocational Teacher of the Year PUBLICATIONS Authored Books (18) Casey Griffiths and Mary Jane Woodger, 50 Relics of the Restoration (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Press, 2020). -

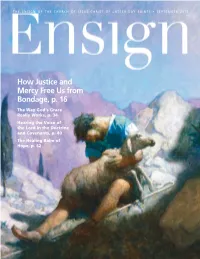

September 2013 Ensign

THE ENSIGN OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • SEPTEMBER 2013 How Justice and Mercy Free Us from Bondage, p. 16 The Way God’s Grace Really Works, p. 34 Hearing the Voice of the Lord in the Doctrine and Covenants, p. 40 The Healing Balm of Hope, p. 62 “But whosoever drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst; but the water that I shall give him shall be in him . springing up into everlasting life.” John 4:14 Contents September 2013 Volume 43 • Number 9 FEATURES 16 The Justice and Mercy of God Elder Jeffrey R. Holland If we can repent of our sins and be charitable with the sins of others, the living Father of us all will reach down to bear us up. 22 Take My Yoke upon You A useful tool for harnessing animals became a central image in the Savior’s invitation to come unto Him. 24 Today’s Young Men Need Righteous Role Models Hikari Loftus Having worked through his own troubled youth, Todd Sylvester strives to reach out to today’s young men. 4 28 Still a Clarion Call “The Family: A Proclamation to the World” acts as a modern title of liberty, providing clarity and MESSAGES guidance to families. FIRST PRESIDENCY MESSAGE 30 Christlike Mercy 30 Randy L. Daybell 4 Saints for All Seasons These scriptural President Dieter F. Uchtdorf accounts from the Savior’s life can teach us VISITING TEACHING MESSAGE ways to be merciful. 7 Self-Reliance 34 His Grace Is Sufficient Brad Wilcox The miracle of Christ’s grace is not just that we can return to heaven but ON THE COVER that we can change so The e nsign of T he ChurC h of Jesus ChrisT of LaTTer-day s ainT s • s epT ember 2013 Front: The Lost Lamb, we feel at home there. -

Dominicus Carter

DOMINICUS CARTER LATTER-DAY PIONEER By Barton L. Carter Dedicated to – and in memory of – his great-grandson, John Deloy Carter, who was always proud of his Carter heritage. The question was once asked of me. “Why should I be concerned with the lives of ancestors beyond my memory or out of my experience?” Why, indeed, should anyone concern himself with those long dead? Said Helaman to his sons, Nephi and Lehi: “Behold, my sons, . I have given unto you the names of our first parents who came out of the land of Jerusalem; and this I have done that when you remember your names ye may remember them; and when ye remember them ye may remember their works; and when ye remember their works ye may know how that it is said, and also written, that they were good. “Therefore, my sons, I would that ye should do that which is good, that it may be said of you, and also written, even as it has been said and written of them.” Book of Mormon, Helaman 5:6-7 ©1997 by Barton L. Carter, 2599 East Hidden Canyon Lane Sandy, Utah 84092 Dominicus Carter, our great progenitor, was one of the tens of thousands who a hundred and fifty years ago came to these valleys to claim the Zion that nobody else wanted. We have but few of his words and thoughts but his works stand as testimony of his great faith and unfailing zeal for the establishment of Zion and the Kingdom of God. He was the friend of the prophets of the restoration. -

The First Mormons of Western Maine 1830--1890

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Winter 2010 Western Maine saints: The first Mormons of western Maine 1830--1890 Carole A. York University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation York, Carole A., "Western Maine saints: The first Mormons of western Maine 1830--1890" (2010). Master's Theses and Capstones. 140. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/140 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 44 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI WESTERN MAINE SAINTS: THE FIRST MORMONS OF WESTERN MAINE 1830-1890 By CAROLE A. YORK BA, University of Redlands, 1963 MSSW, Columbia University, 1966 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History December, 2010 UMI Number: 1489969 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Letter from David Whitmer to Nathan West Concerning Caldwell County, Missouri, Property Once Owned by King Follett

Scott H. Faulring: David Whitmer Letter 127 Letter from David Whitmer to Nathan West Concerning Caldwell County, Missouri, Property Once Owned by King Follett Scott H. Faulring Filed away in the David Whitmer Collection at the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS) Archives is an inconspicuous, handwritten copy of a November 1849 letter from David Whitmer to Nathan A. West.1 In this carefully worded letter, Whitmer responded to West’s inquiry about a legal title to land once owned by the late Mormon elder King Follett.2 One senses from reading the letter that although David was trying to be helpful to his friend, he wanted to distance himself legally from liability in a decade-old property question. This letter is historically significant and interesting for a variety of rea- sons. First, there are few surviving letters from David Whitmer written dur- ing the first ten to fifteen years after he separated himself from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.3 Second, this retained copy, and most probably the dispatched original, was handwritten by Oliver Cowdery—just a little more than three months before he died. As such, it is the last-known handwriting of Mormonism’s Second Elder.4 Third, the letter’s cautious, legalistic wording is not from the mind of David Whitmer but was composed by Oliver Cowdery, the lawyer. As such, it is the only example of his legal writing from his fourteen-month stay in Richmond.5 Fourth, the items dis- cussed in the letter evidence the confused state of affairs existing in Far West, Missouri, at the time the Latter-day Saints were forced to flee the state in 1839.6 SCOTT H. -

The Kirtland Economy Revisited: a Market Critique of Sectarian Economics

The Kirtland Economy Revisited: A Market Critique of Sectarian Economics Marvin S. Hill, C. Keith Rooker, and Larry T. Wimmer Acknowledgements Our indebtedness to others is unusually great. In addition to those who have read, criticized, and helped improve our manuscript, we have received suggestions which could have resulted in articles for the authors themselves but for their unselfish contributions to our work. In a real sense, this study is the result of a group effort beyond the three authors listed. Questions raised by Mr. Paul Sampson while working on a graduate history paper provided the immediate impetus for the study. He also generously provided us with all of his notes and bibliographic work. Initial encouragement and the financial support was provided by Professors Leonard J. Arrington and Thomas G. Alexander, direc- tors of the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at Brigham Young University. Our two research assistants, Michael Cleverley and Maureen Arce- neaux, were extraordinarily helpful. Not only did they perform the bur- densome task of gathering and manipulating an enormous amount of data with great skill, but they also made several suggestions which led to innovative and fruitful areas of research. For example, the procedure used to estimate annual population from a combination of census and annual tax records was suggested by Mr. Cleverley. Professor Peter Crawley of the Mathematics Department at Brigham Young University suggested the procedure used to estimate the circula- tion of Kirtland notes, provided us with lists of serial numbers for those notes which he has collected over the years, and made other helpful suggestions regarding the bank. -

Narrating Jane: Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Arrington Annual Lecture Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures 9-24-2015 Narrating Jane: Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman Quincy D. Newell Hamilton College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_lecture Part of the History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Newell, Quincy D., "Narrating Jane: Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman" (2015). 21st annual Arrington Lecture. This Lecture is brought to you for free and open access by the Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arrington Annual Lecture by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEONARD J. ARRINGTON MORMON HISTORY LECTURE SERIES No. 21 Narrating Jane Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman by Quincy D. Newell September 24, 2015 Sponsored by Special Collections & Archives Merrill-Cazier Library Utah State University Logan, Utah Newell_NarratingJane_INT.indd 1 4/13/16 2:56 PM Arrington Lecture Series Board of Directors F. Ross Peterson, Chair Gary Anderson Philip Barlow Jonathan Bullen Richard A. Christenson Bradford Cole Wayne Dymock Kenneth W. Godfrey Sarah Barringer Gordon Susan Madsen This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-1-60732-561-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60732-562-8 (ebook) Published by Merrill-Cazier Library Distributed by Utah State University Press Logan, UT 84322 Newell_NarratingJane_INT.indd 2 4/13/16 2:56 PM Foreword F. -

The Mormon Mission in Herefordshire and Neighbouring Counties, 1840 to 1841

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs The Mormon Mission in Herefordshire and Neighbouring Counties, 1840 to 1841 Student Dissertation How to cite: Davis, Hilary Anne (2019). The Mormon Mission in Herefordshire and Neighbouring Counties, 1840 to 1841. Student dissertation for The Open University module A826 MA History part 2. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Redacted Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk The Mormon Mission in Herefordshire and Neighbouring Counties, 1840 to 1841 Hilary Anne Davis BA (Hons.) Humanities with Religious Studies (Open) A dissertation submitted to The Open University for the degree of MA in History January 2019 WORD COUNT: 15,533 Hilary Anne Davis Dissertation ABSTRACT This study focusses on the Mormon mission to Britain in the nineteenth century, specifically the time spent in Herefordshire and on the borders of Worcestershire and Gloucestershire in 1840 to 1841. This mission was remarkable because of the speed with which an estimated 1800 rural folk were ready to be baptised into a new form of Christianity and because of the subsequent emigration of many of them to America. This investigation examines the religious, social and economic context in which conversion and emigration were particularly attractive to people in this area. -

Show Notes & Transcripts

“For the Salvation of Zion” Show Notes & Transcripts Podcast General Description: Follow Him: A Come, Follow Me Podcast with Hank Smith & John Bytheway Do you ever feel that preparing for your weekly Come, Follow Me lesson falls short? Join hosts Hank Smith and John Bytheway as they interview experts to make your study for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Come, Follow Me course not only enjoyable but original and educational. If you are looking for resources to make your study fresh, faithful, and fun--no matter your age--then join us every Sunday. Podcast Episode Descriptions: Part 1: Have you ever received an assignment yet didn’t have the skills to complete it? Join Dr. Susan Easton Black as we discuss Joseph, Hyrum, and others who were chastened for not building a temple and how the pattern for becoming like the Lord is established. Also, Dr. Black teaches how the temple amplifies our spiritual gifts and how the Saints can stop living beneath our privileges. Part 2: Were the early Saints required to observe their covenants by sacrifice? Dr. Black returns to explain how the Saints are preparing for temple covenants and how the Lord tempers their expectations of Zion. We also discuss how the Lord is anxious to bless the Saints with temple blessings, power, and protection. Timecodes: Part 1 ● 00:00 Welcome to followHIM with Hank Smith and John Bytheway ● 00:54 Introduction of Dr. Susan Easton Black ● 02:49 Background to Sections 94-97 ● 03:39 Kirtland Temple Building Committee established ● 07:23 Printing to happen in -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005

Journal of Mormon History Volume 31 Issue 3 Article 1 2005 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2005) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 31 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol31/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES • --The Case for Sidney Rigdon as Author of the Lectures on Faith Noel B. Reynolds, 1 • --Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith: Genealogical Applications Ugo A. Perego, Natalie M. Myres, and Scott R. Woodward, 42 • --Lucy's Image: A Recently Discovered Photograph of Lucy Mack Smith Ronald E. Romig and Lachlan Mackay, 61 • --Eyes on "the Whole European World": Mormon Observers of the 1848 Revolutions Craig Livingston, 78 • --Missouri's Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons Stephen C. LeSueur, 113 • --Artois Hamilton: A Good Man in Carthage? Susan Easton Black, 145 • --One Masterpiece, Four Masters: Reconsidering the Authorship of the Salt Lake Tabernacle Nathan D. Grow, 170 • --The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism Ronald W. Walker, 198 • --Kerstina Nilsdotter: A Story of the Swedish Saints Leslie Albrecht Huber, 241 REVIEWS --John Sillito, ed., History's Apprentice: The Diaries of B. -

Susan Easton Balck, Ed., Stories from the Early Saints: Converted by the Book of Mormon

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 4 Number 1 Article 40 1992 Susan Easton Balck, ed., Stories from the Early Saints: Converted by the Book of Mormon Daniel C. Peterson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Peterson, Daniel C. (1992) "Susan Easton Balck, ed., Stories from the Early Saints: Converted by the Book of Mormon," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 40. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol4/iss1/40 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Author(s) Daniel C. Peterson Reference Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 4/1 (1992): 13–19. ISSN 1050-7930 (print), 2168-3719 (online) Abstract Review of Stories from the Early Saints: Converted by the Book of Mormon (1992), edited by Susan Easton Black. Susan Easton Black, ed. Stories from the Early Saints: Converted by the Book 0/ Mormon. Salt Lake City: Bookeraft, 1992. xiii + 104 pp. $9.95. Reviewed by Daniel C. Peterson This volume represents a decade's of collecting stories concerning people who joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in its early days because of the Book of Mormon. Like Eugene England's fine earlier anthology, Converted to Christ through the Book of Mormon, its completion was inspired by the October 1988 conference address in which President Ezra Taft Benson "challenge[d] our Church writers, teachers, and leaders to tell us more Book of Mormon conversion stories that will strengthen our faith and prepare great missionaries."1 Fittingly, each book is dedicated to President Benson, a prominent and prophetic advocate of the Book of Mormon.