Boston: the Red Sox, the Celtics, and Race, 1945-1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red Sox Game Notes Page 2 TODAY’S STARTING PITCHER 19-JOSH BECKETT, RHP 2-4, 5.97 ERA, 6 Starts 2012: 2-4, 5.97 ERA (23 ER/34.2 IP) in 6 GS 2011 Vs

BOSTON RED SOX (16-19) vs. SEATTLE MARINERS (16-21) Tuesday, May 15, 2012 • 4:05 p.m. ET • Fenway Park, Boston, MA RHP Josh Beckett (2-4, 5.97) vs. RHP Blake Beavin (1-3, 4.32) Game #36 • Home Game #20 • TV: NESN • Radio: WEEI 93.7 FM/850 AM, WWZN 1510 AM (Spanish) FOUR IN HAND: The Red Sox began a 2-game series with THANKS, WAKE DAY: Today the Red Sox honor Tim Wake- the Mariners last night with a 6-1 victory for the club’s 4th fi eld in a pre-game ceremony expected to begin at approxi- RED SOX RECORD BREAKDOWN Overall ......................................... 16-19 straight win...Boston has won 4 straight games for the 1st mately 3:30 p.m....The knuckleballer won more games at AL East Standing ................ 5th, -5.5 GB time since a season-high 6-game win streak from 4/23-28. Fenway Park than any pitcher in history and played 19 years At Home ......................................... 8-11 This 4-game stretch is Boston’s longest home win streak in the Majors, including 17 with Boston...He announced his On Road ........................................... 8-8 of the season and the club’s longest overall since a 9-game retirement on 2/17 at JetBlue Park at Fenway South. In day games .................................. 4-10 home win streak from 7/5-24/11. In night games ............................... 12-9 The Red Sox have outscored opponents 29-8 during the VS. THE MARINERS: Boston and Seattle meet 9 times in April ............................................. 11-11 4-game run, including 22-3 over the last 3 tilts...Red Sox 2012...The current 2-game set is their only series at Fenway May ................................................. -

Iplffll. Tubeless Or Tire&Tube

THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. M Billy Meyer Dead at 65; Lead Stands Up MONDAY. APBIL 1, 1957 A-17 Long Famous in Baseball , i Gonzales Quitting Pro Tour . - May Injured - ' • •• As 'v Palmer Wins mEBIIHhhS^^s^hESSHSI KNOXVILLE, Term., April. 1 ¦ In to Heal Hand V9T (VP).—Death has claimed William MONTREAL, April 1 (VP).—Big : wall to pro to give Adam (Billy) Meyer, major turn Gonzales Oonzales, king of profes- some competition, avail- league “manager of the year” Pancho ¦ was not Azalea Tourney sional tennis, today decided to -1 able for comment but it could ; with the underdog Pittsburgh quit Kramer’s troupe after : as any surprise Pirates in 1948 and of the Jack not have come one WILMINGTON, N. C.. April 1 May . best-known minor league man- Its last American match 26. to him. (VP).—Although he outshot only Plagued by a cyst on his racket ; When the American segment ! agers of all time. four of the 24 other money win- hand, Gonzales said: of the tour opened in New Yorl The 65-yfear-old veteran of 46 ners in the Azalea Open golf “Ineed a rest. I’ve been play- February 17, Gonzales was ljl years player, ¦ as manager, scout tournament’s final round, Arnold ing continuously for 18 months > pain and he said that if this and “trouble shooter” died in a Palmer’s 54-hole lead stood up and I want to give my hand a injury not heal, he miglit and i did hospital yesterday of a heart and ” he eased out with a one- chance to heal.” have to quit. -

Kings Boston

Location factfile: Kings Boston In this factfile: Explore Boston Explore Kings Boston School facilities Local map Courses available Accommodation options School life and community Activities and excursions Clubs and societies Enrichment opportunities Kings Boston Choose Kings Boston 1 One of the great sports and music cities 2 American culture, European style 3 Downtown living and learning Location factfile: Kings Boston Explore Boston Boston is one of the great American cities, and the perfect place to be an international student. World-renowned as one of the great capitals of learning, Boston is home to over 50 universities and colleges. This is a city with a rich history but also has a modern, dynamic centre with a wealth of entertainment options — offering something for everyone! Key facts: Boston Location: Massachusetts, north east USA Population: 640,000 Nearest airports: Boston Logan International Airport Nearest cities: New York, Providence Boston highlights The Freedom Trail Sports Learn all about the history of the American Revolution through the Enjoy world-famous sports teams in action such as the Boston Red unique collection of museums, churches, meeting houses, parks Sox (baseball) and New England Patriots (American football) in this and ships that make up The Freedom Trail. great sporting city Shopping Museums and galleries Explore and enjoy the city’s many shopping opportunities — try the Take time out to visit some of the city’s many art exhibitions, such as Prudential Center and open-air Faneuil Hall Marketplace, and the at the Institute of Contemporary Art, The Museum of Fine Arts as numerous boutiques along Newbury and Charles Streets. -

Liv E Auction Live Auction

Live Auction 101 Boston Celtics “Travel with the Team” VIP Experience $10,000 This is the chance of a lifetime to travel with the Boston Celtics and see them on the road as a Celtics VIP! You and a guest will fly with the Boston Celtics Live Auction Live on their private charter plane on Friday, January 5, 2018 to watch them battle the Brooklyn Nets on Saturday, January 6, 2018. Your VIP experience includes first-class accommodations at the team hotel, two premium seats to the game at the Barclays Center—and some extra special surprises! Travel must take place January 5-6, 2018. At least one guest must be 21 or older. Compliments of The Boston Celtics Shamrock Foundation 102 The Ultimate Fenway Concert Experience $600 You and three friends will truly feel like VIPs at the concert of your choice in 2018 at Fenway Park! Before the show, enjoy dinner in the exclusive EMC Club at Fenway Park. Then, you’ll head down onto the historic ball park’s field to take in the concert from four turf seats. Also includes VIP parking for one car. Although the full concert schedule for 2018 is yet to be announced, the Foo Fighters “Concrete and Gold Tour” plays at Fenway Park on July 21 and 22, 2018. Past performers have included Billy Joel, James Taylor, Lady Gaga and Pearl Jam. Valid for 2018 only and must be scheduled for a mutually agreeable date. Compliments of the Boston Red Sox 103 Street Hockey with Patrice Bergeron and Brad Marchand $5,000 Give your favorite young hockey stars a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to play with the best—NHL All-Stars and Boston Bruins forwards, Patrice Bergeron and Brad Marchand! Your child and 19 friends will play a 60-minute game of street hockey with Bergeron and Marchand at your house. -

Harlem Globetrotters Adrian Maher – Writer/Director 1

Unsung Hollywood: Harlem Globetrotters Adrian Maher – Writer/Director 1 UNSUNG HOLLYWOOD: Writer/Director/Producer: Adrian Maher HARLEM GLOBETROTTERS COLD OPEN Tape 023 Ben Green The style of the NBA today goes straight back, uh, to the Harlem Globetrotters…. Magic Johnson and Showtime that was Globetrotter basketball. Tape 030 Mannie Jackson [01:04:17] The Harlem Globetrotters are arguably the best known sports franchise ….. probably one of the best known brands in the world. Tape 028 Kevin Frazier [16:13:32] The Harlem Globetrotters are …. a team that revolutionized basketball…There may not be Black basketball without the Harlem Globetrotters. Tape 001 Sweet Lou Dunbar [01:10:28] Abe Saperstein, he's only about this tall……he had these five guys from the south side of Chicago, they….. all crammed into ….. this one small car. And, they'd travel. Tape 030 Mannie Jackson [01:20:06] Abe was a showman….. Tape 033 Mannie Jackson (04:18:53) he’s the first person that really recognized that sports and entertainment were blended. Tape 018 Kevin “Special K” Daly [19:01:53] back in the day, uh, because of the racism that was going on the Harlem Globetrotters couldn’t stay at the regular hotel so they had to sleep in jail sometimes or barns, in the car, slaughterhouses Tape 034 Bijan Bayne [09:37:30] the Globetrotters were prophets……But they were aliens in their own land. Tape 007 Curly Neal [04:21:26] we invented the slam dunk ….., the ally-oop shot which is very famous and….between the legs, passes Tape 030 Mannie Jackson [01:21:33] They made the game look so easy, they did things so fast it looked magical…. -

History Book.Indd

HHISTORYISTORY & RRECORDSECORDS CCALVINALVIN MMURPHYURPHY VS.VS. BUFFALOBUFFALO IINN TTHEHE ‘TAPS’‘TAPS’ GALLAGHERGALLAGHER CENTERCENTER DDURINGURING THETHE 1969-701969-70 SEASONSEASON All-Time Scorers 1. Calvin Murphy, 1966-70 .....................................2,548 28. Manny Leaks, 1964-68 ........................................1,243 55. Richie Veith, 1955-59 ............................................858 2. Juan Mendez, 2001-05.........................................2,210 29. Anthony Nelson, 2007-11 ..................................1,215 56. Joe Maddrey, 1959-63 ............................................847 3. Antoine Mason, 2010-14 ...................................1,934 30. Alvin Cruz, 2001-05 ............................................1,207 57. John Spanbauer, 1948-52 ......................................843 4. Tyrone Lewis, 2006-10 .......................................1,849 31. Demond Stewart, 1999-01 .................................1,195 58. Gary Bossert, 1983-87 .......................................... 833 5. Charron Fisher, 2004-08 ...................................1,799 32. Zeke Sinicola, 1947-51 ........................................1,188 59. Eldridge Moore, 1985-89...................................... 829 6. Tremmell Darden, 2000-04 ................................1,729 33. Vern Allen, 1974-78.............................................1,183 60. Fred Schwab, 1942-43, 45-48 ...............................827 7. Chris Watson, 1993-97 ........................................1,711 34. Ken Glenn, 1959-63 ............................................1,177 -

2006 Media Guide.Indd

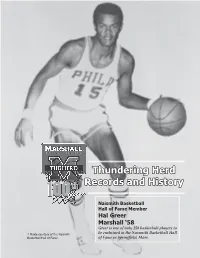

TThunderinghundering HerdHerd RRecordsecords aandnd HHistoryistory Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame Member Hal Greer Marshall ‘58 Greer is one of only 258 basketball players to * Photo courtesy of the Naismith be enshrined in the Naismith Basketball Hall Basketball Hall of Fame. of Fame in Springfi eld, Mass. 9977 r “Consistency,” Hal Hal Greer was named one of the NBA’s Top e Greer once told the e 50 Players in the late 90’s. He averaged 19 r Philadelphia Daily points, fi ve rebounds, and four assists in his G News. “For me, that was l NBA career. a the thing … I would like H Hal Greer to be remembered as a great, consistent player.” Over the course of rebounds and 4.4 assists per contest. With injuries limiting the 15 NBA seasons Schayes to 56 games, Greer took over the team’s scoring turned in by the slight, mantle. He ranked 13th in the NBA in scoring and ninth soft -spoken Hall of in free-throw percentage (.819). In the 1962 NBA All-Star Fame guard from West Game, Greer racked up a team-high nine assists - one more Virginia, consistency than the legendary Bob Cousy - and hauled in 10 rebounds, was indeed the thing. just two fewer than another legend, Bill Russell. Greer led He turned in quality the Nationals to the playoff s, where they fell to Warriors in performances almost every night, scoring 19.2 points the Eastern Division Semifi nals. per game during his career, playing in 1,122 games, and The smooth guard broke into the ranks of the top 10 racking up 21,586 points (14th on the all-time list). -

Bill Russell to Speak at University of Montana December 3

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 11-25-1969 Bill Russell to speak at University of Montana December 3 University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "Bill Russell to speak at University of Montana December 3" (1969). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 5342. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/5342 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMMEDIATELY $ 13 O r t S herrin/js ____ ___ ___________________________ 11/ 25/69 state + cs Information Services • University of montana • missoula, montana 59801 • (406) 243-2522 BILL RUSSELL TO SPEAK AT UM DEC. 3 MISSOULA-- Bill Russell, star basketball player-coach for the Boston Celtics, will speak at the University of Montana Dec. 3. Russell, the first Negro to manage full-time in a major league of any sport, will lecture in the University Center Ballroom at 8:15 p.m. Dec. 3. His appearance, which is open to the public without charge, is sponsored by the Program Council of the Associated Students at UM. Russell's interests are not confined to the basketball court. -

Ucla Men's Basketball

UCLA MEN’S BASKETBALL March 25, 2006 Bill Bennett/Marc Dellins /310-206-7870 For Immediate Release UCLA Men’s Basketball/NCAA Between Game Notes NO. 7 UCLA PLAYS NO. 4 MEMPHIS IN NCAA REGIONAL FINAL IN OAKLAND ON SATURDAY, WINNER ADVANCES TO “FINAL FOUR” IN INDIANAPOLIS; BRUINS EDGE GONZAGA 73-71 ON THURSDAY IN “SWEET 16” CONTEST No. 7/No. 8 UCLA (30-6/Pac-10 14-4, Regular Season, Tournament Champions/No. 2 Seed) vs. No. 4/No. 3 MEMPHIS (33-3/Conference USA 13-1, Regular Season, Tournament Champions/No. 1 Seed) - Saturday, March 25/Oakland, CA/Oakland Arena/4:05 p.m. PT/TV- CBS, Gus Johnson and Len Elmore/Radio-570AM, with Chris Roberts and Don MacLean. Tentative UCLA Starters F- 21 Cedric Bozeman 6-6, Sr., 7.8, 3.2 F-23 Luc Richard Mbah a Moute 6-8, Fr., 9.1, 8.1 C- 15 Ryan Hollins 7-01/2, Sr., 6.7, 4.5 G-1 Jordan Farmar 6-2, So., 13.6, 2.5 G-4 Arron Afflalo 6-4, So., 16.2, 4.3 UCLA vs. Memphis – The Tigers advanced with an 80-64 victory over Bradley, led by Rodney Carney’s 23 points. Memphis has won 22 of its last 23 games and has a seven-game winning streak. This will be the team’s second meeting this season – on Nov. 23 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden, Memphis defeated UCLA 88-80 in an NIT Season Tip-Off semifinal. Last Meeting - Nov. 23 – No. 11 Memphis 88, No. -

Downtrodden Yet Determined: Exploring the History Of

DOWNTRODDEN YET DETERMINED: EXPLORING THE HISTORY OF BLACK MALES IN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL AND HOW THE PLAYERS ASSOCIATION ADDRESSES THEIR WELFARE A Dissertation by JUSTIN RYAN GARNER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, John N. Singer Committee Members, Natasha Brison Paul J. Batista Tommy J. Curry Head of Department, Melinda Sheffield-Moore May 2019 Major Subject: Kinesiology Copyright 2019 Justin R. Garner ABSTRACT Professional athletes are paid for their labor and it is often believed they have a weaker argument of exploitation. However, labor disputes in professional sports suggest athletes do not always receive fair compensation for their contributions to league and team success. Any professional athlete, regardless of their race, may claim to endure unjust wages relative to their fellow athlete peers, yet Black professional athletes’ history of exploitation inspires greater concerns. The purpose of this study was twofold: 1) to explore and trace the historical development of basketball in the United States (US) and the critical role Black males played in its growth and commercial development, and 2) to illuminate the perspectives and experiences of Black male professional basketball players concerning the role the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA), collectively considered as the Players Association for this study, played in their welfare and addressing issues of exploitation. While drawing from the conceptual framework of anti-colonial thought, an exploratory case study was employed in which in-depth interviews were conducted with a list of Black male professional basketball players who are members of the Players Association. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Letter to collector and introduction to catalog ........................................................................................ 4 Auction Rules ............................................................................................................................................... 5 January 31, 2018 Major Auction Top Ten Lots .................................................................................................................................................. 6-14 Baseball Card Sets & Lots .......................................................................................................................... 15-29 Baseball Card Singles ................................................................................................................................. 30-48 Autographed Baseball Items ..................................................................................................................... 48-71 Historical Autographs ......................................................................................................................................72 Entertainment Autographs ........................................................................................................................ 73-77 Non-Sports Cards ....................................................................................................................................... 78-82 Basketball Cards & Autographs ............................................................................................................... -

The NCAA News

VOL. 11 l NO. 1 JANUARY 1, 1974 ROBERT S. DORSEY ROBERT B. MeCURRY, Jr. Dr. ROBERT J. ROBINSON EUGENE T. ROSSIDES HOWARD H. CALLAWAY IOf Engine Expel-l Chrysler Executive Georgim Pastor Washingfon Aftorney socref.ary of rho Army Varied Careers Represented on Silver Anniversary List The Secretary of the Army, a third district of Georgia in 196% moved up the ladder to his cur- first black elected to Tau Beta Pi, and the F-86 fighters to the GE% lawyer, a minister, an engineer 66 and was the Republican can- rent position. He started as a dls- the National Engineering Honor which will power the giant super- and a business executive are the didate for the Governor of Geor- trict sales manager for Dodge in Society. He currently serves as sonic transports of the future. He National Collegiate Athletic As- gia in 1966. Green Bay, Wise. Manager of Evaluation Technol- is credited with developing a sociation’s 1974 Silver Anniver- McCurry is on the Board of ogy and Methods Development in complex computer simulation sary winners in the College Ath- ROBERT B. McCURRY, JR. Directors of the Fellowship of the Flight Propulsion Division of technique to predict the eflect of letics Top Ten. McCurry is the Vice-President Christian Athletes and the Michi- the General Electric Company in tolerances on engines and their The five honorees are Secretary of TJ. S. Automotive Sales and gan State University School of Evendale, Ohio. He specializes in inner parts. of the Army Howard H. Callaway Service for Chrysler Corporation Business. He is also on the Board jet engine design and test pro- He has received numerous hon- of Washington, D.C.: Chrysler in Detroit.