Sport and Play for All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Sports Tourism on Small Scale Business Development in Sri Lanka: International Cricket Match

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 3, Issue 10, October 2016, PP 33-38 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) The Impact of Sports Tourism on Small Scale Business Development in Sri Lanka: International Cricket Match Vimukthi Charika Wickramaratne Senior Lecturer, Department of Sports Sciences and Physical Education, University of Kelaniya J.A.Prasansha Kumari Senior Lecturer, Department of Economics, University of Kelaniya ABSTRACT Sports tourism refers to travel which involves either observing or participating in a sporting event apart from their usual environment. Sports tourism in a fast growing sector of the Sri Lankan travelling industry since Cricket are more popular sports game in the country. This study intends to analyze the impact of these popular sports events for creating and developing small scale business in the country. Primary data gathered from 150 small entrepreneurs around Keththarama Cricket Ground in Sri Lanka. Collected data analyzed using descriptive research methods. The study revealed that local and international visitors for cricket games had impacted on small scale business activities such as retail, handicraft, transports, vehicle parking, small restaurant, hotels, foods and beverage industry. In addition, it was identified that these type of small business are sessional income generating activities for the short period. Keywords: Sports Tourism, Small Scale Business, Cricket, entrepreneurs INTRODUCTION Tourism is an important sector for economic development in a country. People usually travel for many reasons. Sport is one of the important reason for promoting tourist industry. With the development of the society and improvement of people living standard, sports tourism gradually becomes one of the faster growing industry. -

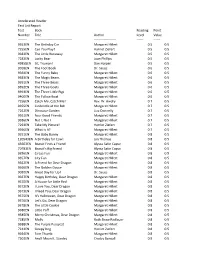

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------- ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------ ------ 9353EN The Birthday Car Margaret Hillert 0.5 0.5 7255EN Can You Play? Harriet Ziefert 0.5 0.5 9382EN The Little Runaway Margaret Hillert 0.5 0.5 7282EN Lucky Bear Joan Phillips 0.5 0.5 49858EN Sit, Truman! Dan Harper 0.5 0.5 9018EN The Foot Book Dr. Seuss 0.6 0.5 9364EN The Funny Baby Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9383EN The Magic Beans Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9391EN The Three Bears Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9392EN The Three Goats Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9393EN The Three Little Pigs Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9400EN The Yellow Boat Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 7256EN Catch Me, Catch Me! Rev. W. Awdry 0.7 0.5 9355EN Cinderella at the Ball Margaret Hillert 0.7 0.5 7262EN Dinosaur Garden Liza Donnelly 0.7 0.5 9361EN Four Good Friends Margaret Hillert 0.7 0.5 9386EN Not I, Not I Margaret Hillert 0.7 0.5 7293EN Take My Picture! Harriet Ziefert 0.7 0.5 9396EN What Is It? Margaret Hillert 0.7 0.5 9351EN The Baby Bunny Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 120543EN A Birthday for Cow! Jan Thomas 0.8 0.5 43663EN Biscuit Finds a Friend Alyssa Satin Capuc 0.8 0.5 70783EN Biscuit's Big Friend Alyssa Satin Capuc 0.8 0.5 9356EN Circus Fun Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 9357EN City Fun Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 9362EN A Friend for Dear Dragon Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 9366EN The Golden Goose Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 9020EN Great Day for Up! Dr. -

POLO+10 World 02/2020

WOR L D POLO+10 WORLD – The Polo Magazine • Est. 2004 • Published Worldwide I I/ 2020, Volume 9 • No 25 100,00 AED 1.500,00 ARS 35,00 AUD 10,00 BHD 25,00 CHF 165,00 CNY 20,00 EUR 30,00 GBP 190,00 HKD 1.700,00 INR 2.700,00 JPY 90,00 QAR 1.600,00 RUB 35,00 SGD 25,00 USD 350,00 ZAR 1972 DPV + EDITORIAL POLO 10 WORLD II / 2020 3 D . V E . U E T S D C N H A ER RB POLO VE DEAR FRIENDS OF POLO+10, DEAR POLO FRIENDS, the Covid-19 pandemic and its consequences influence our everyday life during these weeks. The first concern of course is for our families and friends. Protecting their health and limiting the spread of the virus still is our grea- test common obligation. We are all asked to adapt to the current circumstances, follow the restrictions in our sport and the advice for per- sonal distancing where necessary. And we can see that in following official advice we are successfully fighting Covid-19. As a result in more and more countries the strict measures will be eased in the upcoming weeks, a return to limited training slowly is possible. Polo clubs and stables affected from the restric- tions have mastered the special challenges very well. Des- pite the sometimes limiting possibilities, the care for the horses was and is always upheld. And fortunately the good and close cooperation with the authorities has made it possible to quickly implement individual training plans. -

Prevention of Sports Injuries in Sri Lanka: What Do We Know About Injuries in Our Athletes?

Gamage J.P. et al. SLJSEM, 2019/2020, 2:1 DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/sljsem.v2i1.12 REVIEW ARTICLE Prevention of sports injuries in Sri Lanka: what do we know about injuries in our athletes? Prasanna J. Gamage1, Alex Kountouris2, Caroline F. Finch1, Lauren V. Fortington1 Abstract In terms of safeguarding the health and well-being of athletes in Sri Lanka, a primary focus has always been toward the treatment of injuries after they have occurred and promoting rehabilitation back into sport. There has been little attention towards the primary prevention of injuries in Sri Lankan sports. As a developing sporting nation, the benefits of injury prevention are immense: from a public health and financial perspective, through to individual benefits for athletes’ physical, psychological and social health. Understanding the reasons behind the lack of motive towards sports injury prevention in the country, and challenges in developing and implementing injury prevention measures in the field is useful so that these reasons can be addressed and overcome. Based on recent experience in conducting injury prevention research among Sri Lankan junior cricketers, this article discusses injury prevention principles in sport and provides directions for future sport injury prevention research in Sri Lanka. Keywords: Injury prevention, Cricket, Athletic injuries Introduction In addition to the health benefits, participation in The prevalence of overweight and obese sports and physical activity comes with abundant individuals has increased over the last three social and psychological benefits [3]. This is true decades, and is projected to rise to an estimated particularly for adolescent and youth, as social 58% of the world's adult population by 2030 [1]. -

Caught Between Nationalism and Fair Reporting, the Hoot, Pp

Deakin Research Online This is the published version: Rodrigues, Usha M. 2008, Caught between nationalism and fair reporting, The Hoot, pp. 1-1. Available from Deakin Research Online: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30051462 Every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that permission has been obtained for items included in Deakin Research Online. If you believe that your rights have been infringed by this repository, please contact [email protected] Copyright : 2008, Thehoot.org Caught between nationalism and fair reporting http://www.thehoot.org/web/home/story.php?storyid=2885 Caught between nationalism and fair reporting The oxymoron of 'fair sports coverage' is on stark display during this crisis in the contest between India and Australia. USHA M RODRIGUES on the Australian media's responses to the cricket controversies Down Under. Posted/Updated Tuesday, Jan 08 16:06:48, 2008 The hot controversy of banning the Indian cricketer Harbhajan Singh from three test matches two days ago, and the falling out between the Australian and Indian cricket teams have caught the Australian media by surprise. The oxymoron of 'fair sports coverage' is on stark display during this crisis in the International cricket contest between India and Australia. There are a number of issues plaguing the current cricket sports coverage from Sydney and elsewhere of the crisis, where Indian cricket team has threatened to abandon the Australian tour after two test matches. The Indian cricket players are incensed by the 'unfair' ruling on one of their players, when Australian players continue to play the game 'hard' and allegedly indulge in sledging more than any other cricket team. -

Introduction

Introduction The 2012-2013 school year saw our first drop in participation in 6 years. We went from an all- time high of 55 clubs down to 54, the product of losing a couple of clubs before gaining one. Additionally, our participation numbers reflected this slight downward trend. This was perhaps the only area though where we saw regression. Our clubs continue to perform at the levels we have become accustomed to and events per club continue to increase yearly. Our biggest areas of growth though were on the marketing and programming fronts. Under the guidance of our Club Sports Council and dedicated marketing team we hosted two successful events in the form of dodgeball and broomball tournaments bringing a diverse range of clubs together in spirited competition and community building. Proceeds from the events were put towards Hurricane Sandy relief and the continuation of our Carbon Off-Set Initiative. Additionally our outreach through digital and social media outlets continues to grow. The following report includes a snapshot of Club Sports this past academic year. In addition to statistics surrounding participation, a brief assessment of our marketing and programming efforts is included. We did not assess leadership outcomes this year as we participated in the Student Life initiative exploring them on a larger scale. A discussion of emerging trends and a list of or club’s numerous accomplishments concludes the report. Thank you for supporting our Club Sports and all the students whose lives at UVM are enriched through their participation. -

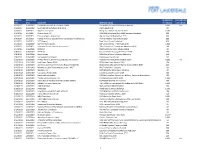

2019 Convention Calendar

ARRIVAL DEPARTURE NUMBER OF CONVENTION DATE DATE ACCOUNT MEETING NAME ATTENDEES CENTER USE 1/2/2019 1/11/2019 United Motorcoach Association - UMA United Motorcoach 2019 Annual Meeting 3,000 Yes 1/2/2019 1/24/2019 South Florida Symphony Orchestra Room Block Only 20 1/3/2019 1/7/2019 Triple Crown Sports Rising Stars Winter Showcase 2019 2,900 1/3/2019 1/6/2019 Destiny Cove LLC 2019 Old Hollywood Glam-MAC Steppers Weekend 200 1/4/2019 1/7/2019 Exclusive Sports Marketing Dig the Beach Volleyball Jan 2019 600 1/4/2019 1/6/2019 Florida Panthers IceDen (former Saveology/incredible Ice) Premier Hockey Tournament 2018 300 1/4/2019 1/5/2019 SUTS Report New Years Classic Basketball 820 1/5/2019 1/11/2019 SAP International, Inc. SAP Latin America - FKOM LAC 2019 1,300 1/6/2019 1/9/2019 Specialty Graphic Imaging Association SGIA Congress of Committees Meeting (2019) 100 1/7/2019 1/12/2019 Q'Straint Q'Straint Winter Sales Meeting 2019 20 1/8/2019 1/16/2019 SPATS Inc. National Team Training Pre Season 2018 350 1/9/2019 1/12/2019 World Vision 2019 World Vision’s Pastors Gathering 450 1/9/2019 1/10/2019 Dentaquest Foundation DentaQuest Foundation 50 1/11/2019 1/20/2019 Florida Nursery, Growers & Landscape Association Tropical Plant Industry Exhibition, 2019 7,000 Yes 1/11/2019 1/12/2019 Gold Coast Region BBYO BBYO Gold Coast January 2019 150 1/12/2019 1/19/2019 American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) Bioprocessing Equipment Standards Committee (BPE) 200 1/13/2019 1/16/2019 Women in Cable Telecommunications - WICT WICT 2019 BMLI - January 60 1/13/2019 1/18/2019 MaxCyte, Inc. -

A National Tradition

Baseball A National Tradition. by Phyllis McIntosh. “As American as baseball and apple pie” is a phrase Americans use to describe any ultimate symbol of life and culture in the United States. Baseball, long dubbed the national pastime, is such a symbol. It is first and foremost a beloved game played at some level in virtually every American town, on dusty sandlots and in gleaming billion-dollar stadiums. But it is also a cultural phenom- enon that has provided a host of colorful characters and cherished traditions. Most Americans can sing at least a few lines of the song “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Generations of children have collected baseball cards with players’ pictures and statistics, the most valuable of which are now worth several million dollars. More than any other sport, baseball has reflected the best and worst of American society. Today, it also mirrors the nation’s increasing diversity, as countries that have embraced America’s favorite sport now send some of their best players to compete in the “big leagues” in the United States. Baseball is played on a Baseball’s Origins: after hitting a ball with a stick. Imported diamond-shaped field, a to the New World, these games evolved configuration set by the rules Truth and Tall Tale. for the game that were into American baseball. established in 1845. In the early days of baseball, it seemed Just a few years ago, a researcher dis- fitting that the national pastime had origi- covered what is believed to be the first nated on home soil. -

Project in Final Stretch

THE WIRE PAGE 1 Canvas chairs, $15 In Today’s Classifieds! AND WEEKLY Charlotte Sun HERALD ARCHIE TO BE SHOT IN COMIC CITIGROUP SETTLES FOR $7B The famous freckle-faced comic book icon is meeting his The settlement represents a moment of reckoning for one of the demise in Wednesday’s installment of “Life with Archie.” country’s biggest and most significant banks. THE WIRE PAGE 1 An Edition of the Sun VOL. 122 NO. 196 AMERICA’S BEST COMMUNITY DAILY TUESDAY JULY 15, 2014 www.sunnewspapers.net $1.00 LIFE STORIES In her own Project in final stretch By BRENDA BARBOSA Bletchley STAFF WRITER PUNTA GORDA — After months of heavy construction that closed circle off parts of Gilchrist Park and ary Merrill is as honest and open as Harborwalk, detoured downtown anyone you’ll meet, but for 50 years traffic and kicked up massive M she kept secret the work she did amounts of dust, the city’s flooding during World War II. mitigation project is finally in the She was sworn to. home stretch. The British-born Local residents, who patiently Merrill, now 92, worked have watched their front yards get at Bletchley Park, the turned into construction zones, say British Code and Cypher they are happy the work is nearing School which famously completion. SUN PHOTO BY BRENDA BARBOSA cracked the German “It doesn’t bother me, but my wife hates all the dust,” said Johnny Construction in Punta Gorda’s historic district is expected to continue through the end of Enigma code. It’s said July, as workers move on to the final leg of the downtown flooding phase 2 project. -

Rank One Sport Game Scheduler Tutorial

Rank One Sport Game Scheduler Tutorial To add a new game schedule, hover your mouse over the Schedules Tab Select Game Scheduler from the drop down menu Step 1. Highlight your School, Sport, Level, and Team Step 2. Enter your Advanced Settings. Advanced settings will allow you to enter the Game Start Time, End Time, Default Home Venue, and Game Type for HOME games in order to make building your schedule faster! In this example 7:30 p.m. will be set as the Start Time, 8:30 p.m. as the End Time, Demo 3 Stadium as the Home Venue, and District as the Game Type, since these will apply to most of the Home games. After you enter your Advanced Settings, click “Save Advanced Settings” before continuing. You will see the “Advanced Settings Saved Successfully!” message at the bottom. *Note: We suggest leaving the End Time as one hour after the Start Time so that the Facility Management piece can work behind the scenes to ensure you do not double book a venue. Parents do NOT see the End Time on the Game Schedule. Step 3. Select the Game Dates from the calendar. *You can select the date multiple times if you have more than one game on the same date* The dates will populate below with your Advanced Settings To adjust the Start Time highlight the existing data and make the appropriate changes For example: Start time is 6:30 type in 0630 (If you do not know the start time check the TBA box) Click Tab on your keyboard After you hit Tab, the End Time will automatically default to one hour after the Start Time We recommend NOT ADJUSTING the End Time Continue filling in the game details All information marked with a red * is required! Type your opponent in the opponent field. -

B.R.A.T.S. Camp

90 FSS/FSK PRSRT STD U.S. POSTAGE 7100 Saber Road PAID F. E. Warren AFB, WY 82005-2911 CHEYENNE, WY The PERMIT NO. 167 To subscribe or unsubscribe: 773-2858 ANTELOPE INSIDE! May 2011 90th Force Support Squadron Monthly Recreation Guide • Spring Warren Cup Golf Tournament May 7 www.funatwarren.com • Mother’s Day Brunch May 8 May Is Fitness Month • May Fitness Day Activities May 11 Look inside for ways to Get Up, Get Out, and Get Moving! • Air Force Wide Teen Lock In/Max Out May 13 • Armed Forces Day Kid’s Run May 21 • Whitewater Rafting Trip May 29 FITNESS Fitness Day May 11 5K Run 1.3 Mile Walk Racquetball Ladder 3 On 3 Basketball Tournament To a degree, Club Membership has its benefits. BootCamp A college degree! B.R.A.T.S. Dodgeball Tournament 500 Words or less could get you CAmp Fitness Orientation Classes $1,000 toward your education! Basic Recreation Adventure Warren Fitness Challenge Training School For Air Force Club members and their family members. Closing Ceremony at Freedom Hall, 3 p.m. To enter, write and submit a 500 word or less essay on, Come support the participants of this “My Contribution(s) to the Air Force?” fourteen week challenge. Awards for Submit with entry form to the 90 FSS Commander by 1 July. winning teams and individuals. Entry forms available at the Trial’s End Club, Base Library and the Education Center or on-line at afclubs.com. Club membership ap- Armed Forces Kids Run plications also available at these locations. -

Biola University

Biola University Undergraduate Prospectus 03 We are restless. The world is full of things to know. Stories to tell, mysteries to solve, ideas to think and words to read. But together— People to meet and help and heal, together, we are a foundation for each other. prayers to pray and sunrises to see. Upon which each of us can build our futures. And be free to fall and fail and fumble and find our ways We are restless. and succeed Because there are things to do. over and over and over again— because we support each other. Individually, Lift each other up as we engage and impact the world. we are incomplete, inexperienced, imperfect. “This is a good place to struggle,” we say. As we seek out God in all things. In the twisted ladder of a double helix. In between the lines of literary masterpieces. In the research we conduct. And the conduits of the human mind. In all that we do. All that we are. All that we become. All as one. We We are We are restless. restless. 04 ACADEMICS Attracting the extraordinary and radiatingYou can feel it. The pull of this place. It calls you. impact. Draws in remarkable students from everywhere. And attracts exceptional faculty, too. Fulbright scholars, fellows, National Endowment for the Humanities grant recipients. Thought leaders who enjoy having the freedom to bring their faith to work every day—elevate it, incorporate it and wrestle with it—instead of leaving it at home. Here, Biola faculty can teach from their heads and their hearts.