By Duane Winn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Park' to House 1,200 Condos

Ratner gets 45 days to up ante MTA talks exclusively with Bruce despite his low offer By Jess Wisloski ner’s company, with the hopes of upping its the July 27 meeting that neither bid came commitment of her company to the proj- The Brooklyn Papers bid by the board’s Sept. 29 meeting. close enough to the state authority’s $214 ect, and reiterated Extell’s plans to develop Ratner’s bid offers $50 million up front. million appraised value for the rail yards to 1,940 units of new housing, with 573 As it once was, so it shall be again, It also includes $29 million in renovations justify the board’s interest. mixed-income units. the Metropolitan Transportation of the rail yards (to help pay for the reloca- Compared to Ratner’s bid — which was She said the costs of infrastructure and Authority board decided this week, tion of them required by Ratner’s plan), two years in the making and included any required platform would be paid for when it cast aside the high bidder — $20 million in environmental remediation dozens of support letters from elected offi- by Extell, and again raised an offer pre- / Jori Klein who offered $150 million to develop of the land (which needs to be done in or- cials, a myriad of minority contracting or- sented by Extell on Monday to work with the Long Island Rail Road storage der to develop the site for housing), $182 ganizations and numerous labor unions, Forest City Ratner to add an arena that / Jori Klein yards at Atlantic Avenue — and million to build a platform (to build the the Extell bid — hastily prepared to meet would be developed on private property. -

Win, Lose Or Draw Native Dancer Barely Gets up to Win Thriller

Resorts and Travel jhmflaa f<tf j&pffffe Sport News C **** FOURTEEN PAGES. WASHINGTON, D. C., IfAY 16, 1954 Busby's 4 Hits Futile, Indians Rally in Eighth to Beat Shea, 5-4 Navy Crew Beats Yale by Half Length for 26th Straight Victory Win, Lose or Draw Jim Homers, By FRANCIS STANN CHUCK DRESSEN IS the sensation of the Pacific Coast Takes League League with his handling of Oakland, a seventh-place club last year but now leading the league and threatening to make o$ with the pennant. ... In addition, the attendance . at . Lead .360 has soared. For the entire 1953 season Oakland played to only 130,045 customers; ? in a two-week opening home stand, the Vernon Also Slams Oaks have drawn 70,057 paid. fjff -Mm Homer, but Rosen, Paul Richards must qualify as the most imaginative of all big league managers, in- MP] Avila Follow Suit eluding Casey Stengel. Last year, it By Burton Hawkins may be recalled, one of Richards’ stunts Star Staff Correspondent .was to move his pitcher to third base so JffTJi CLEVELAND, May 15.—Ac- a southpaw reliever could pitch to one customed to bitter defeats, the batter. Last Friday Richards yanked his Senators acquired additional ' good-hitting first baseman, Bob , acidity for their outlook on life Boyd, and today sent Pitcher Bob Keegan (who delivered) when the Indians shoved across two runs in the eighth . to bat for him. Then he finished with “ inning to deal them a 5-4 loss. * Catcher ¦¦ - Sherm Lollar and Third Baseman . - • • •. - ¦ ¦ ¦ . It now has become not a ques- " Grady - Hatton on first base in a 4-3 win over the A’s. -

DODGERS (28-19) Vs

LOS ANGELES DODGERS (28-19) vs. ST. LOUIS CARDINALS (32-16) 1. RHP Carlos Frias (3-2, 5.34) vs. RHP Michael Wacha (7-0, 1.87) May 30, 2015 | 6:15 p.m. CT | Busch Stadium | St. Louis, MO Game 48 | Road Game 20 (7-12) | Night Game 36 (21-14) TV: FOX | Radio: AM 570/KTNQ 1020 AM 2. END THE DROUGHT: The Dodgers and Cardinals meet for the MATCHUP vs. CARDINALS second game of their three-game series tonight, following St. Louis’ Dodgers: 2nd, NL West (0.5 GB) Cardinals: 1st, NL Central (6.5 GA) 3-0 win in the series opener last night. The clubs will meet seven All-Time: LA leads series, 1,016-1,013-16 (11-22 at Busch Stadium) times in a 10-day span (0-1), with the Cardinals traveling to Los 2015: LA trails series, 0-1 (0-1 at Busch Stadium) Angeles for a four-game series starting Thursday at Dodger Stadium. May 29 @ STL: L, 0-3 W: Lackey L: Bolsinger S: Rosenthal Following the weekend in St. Louis, the Dodgers will fly to Denver for a four-game series against the Rockies, which includes a AIN’T IT GRAND-AL: Earlier today, the Dodgers reinstated catcher doubleheader on Tuesday. Yasmani Grandal from the seven-day concussion disabled list and optioned outfielder Chris Heisey to Triple-A Oklahoma City. Grandal With last night’s loss, coupled with a San Francisco win, has posted a .400/.492/.660 slashline in 16 games this month, going the Dodgers dropped out of first place for the first time 20-for-50 with four doubles, three homers and 15 RBI in 16 games, since April 16, a span of 44 days. -

Landscapes Summer 2021

Allow me to introduce myself My name is Jeff Norte and I was recently selected as the new president and chief executive officer of Capital Farm Credit. Although I’m new to the role, I’m not new to Capital Farm Credit. I’ve been fortunate to be part of the leadership team here for more than 10 years as chief credit officer. I’ve had the great benefit of working with, and learning from, one of the best in Ben Novosad, who served as CEO for 35 years. It is an incredible honor for me to follow in Ben’s footsteps to lead and serve such a great company. It is through his long-tenured leadership that our association was able to grow into what it is today. We are a strong and stable organization with a depth of knowledge and experience keenly positioned to help you achieve your dreams. As a cooperative, Capital Farm Credit is owned by you — the ranchers, farmers, landowners and rural homeowners we serve. We have a long tradition of sup- porting agriculture and rural communities with reliable, consistent credit and financial services. We’ve faithfully served our customers for more than a century. As we begin this journey together, I assure you Capital Farm Credit will con- tinue our absolute commitment to providing service and value to our members. And we will remain focused on our core values of commitment, trust, value and family. These values are the daily reminders of why we do what we do. I look forward to getting to know you better. -

Gening F&Fafppcrfls

CLASSIFIED ADS CLASSIFIED ADS SPORTS gening Ppcrfls f&faf WEDNESDAY, APRIL 2, 1952 C ** Williams and Coleman Pass Physicals for Marine Recall May 2 ¦ - ••••••>•••* Win, Lose, or Draw Smith Favored ' aHBm > ¦ ¦ Lovelletle Miss Ted Is Accepted By Francis Stann Star Staff Correspondent Over Flanagan Os 'Dinky' Layup After X-Rays ST. of PETERSBURG, FLA., APRIL 2.—The Detroit Tigers would stand a better chance of winning the American League pennant, Manager Red Rolfe is thinking, if he had minded his Bout Tonight own business back in 1942. In Decides Finale Injured Elbow “Iwas coaching at Yale,” Red began. “One day we played Winner of Uline Fight a Navy team from New London. My best Peoria Coach Heads Red Sox Slugger pitcher was working, but he couldn’t do a May Get Chance Olympic Squad After And Yank Infielder thing with this squat, funny-looking sailor, | At Sandy P* - h who hit three balls well anybody in the Saddler p gs, mmi . Victory Over To as as I H "IB w Kansas Return to Air Duty big leagues today. By George By I Huber nr, ; th* Associated Press By the Associated Press “That night I wrote a note to Paul n m Featherweight PSlf .4 April I Gene Smith, lit- NEW YORK, 2.—The JACKSONVILLE, Fla., April 2. Kritchell,” the former Yankee third baseman tle Washington Negro who can ' record books will show that Clyde knock Pf||| jPlPPjkfl —Ted Williams of the Boston Red continued. “In the note I told Kritchell I | out an opponent with either Lovellette of Kansas rang up the Sox, highest salaried player hand and who highest three-year in didn’t know where this kid belonged a ball has done so jp idKiK Hfiyjjk 'iH scoring total baseball, and Gerry Coleman of on J frequently, ¦ of any player history—- is a 7-5 favorite to in the New York Yankees, passed field, if anywhere, but that he belonged at that I astounding keep his winning string going to- an 1,888 points—but physical examinations today plate with a bat in his hand.” night against the ones for Glen Flanagan of the big guy will never return to duty as Marine air cap- “Itwas Yogi Berra, of course,” a baseball I St. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

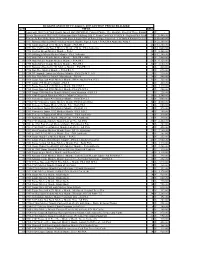

TML NO HITTERS 1951-2017 No

TML NO HITTERS 1951-2017 No. YEAR NAME TEAM OPPONENT WON/LOST NOTES 1 1951 Hal Newhouser Duluth Albany Won 2 1951 Marlin Stuart North Adams Summer Won 3 1952 Ken Raffensberger El Dorado Walla Walla Won 4 1952Billy Pierce Beverly Moosen Won 5 1953 Billy Pierce North Adams El Dorado Won 2nd career 6 1955 Sam Jones El Dorado Beverly Won 1-0 Score, 4 W, 8 K 7 1956 Jim Davis Cheticamp Beverly Won 2-1 Score, 4 W, 2 HBP 8 1956 Willard Schmidt Beverly Duluth Won 1-0 Score, 10 IP 9 1956 Don Newcombe North Adams Summer Won 4-1 Score, 0 ER 10 1957 Bill Fischer Cheticamp Summer Won 2 W, 5 K 11 1957 Billy Hoeft Albany Beverly Won 2 W, 7 K 12 1958 Joey Jay Moosen Bloomington Won 5 W, 9 K 13 1958 Bob Turley Albany Beverly Won 14 1959 Sam Jones Jupiter Sanford Won 15 K, 2nd Career 15 1959 Bob Buhl Jupiter Duluth Won Only 88 pitches 16 1959 Whitey Ford Coachella Vly Duluth Won 8 walks! 17 1960 Larry Jackson Albany Duluth Won 1 W, 10 K 18 1962 John Tsitouris Cheticamp Arkansas Won 13 IP 19 1963 Jim Bouton & Cal Koonce Sanford Jupiter Won G5 TML World Series 20 1964 Gordie Richardson Sioux Falls Cheticamp Won 21 1964 Mickey Lolich Sanford Pensacola Won 22 1964 Jim Bouton Sanford Albany Won E5 spoiled perfect game 23 1964 Jim Bouton Sanford Moosen Won 2nd career; 2-0 score 24 1965 Ray Culp Cheticamp Albany Won *Perfect Game* 25 1965 George Brunet Coopers Pond Duluth Won E6 spoiled perfect game 26 1965 Bob Gibson Duluth Hackensack Won 27 1965 Sandy Koufax Sanford Coachella Vly Won 28 1965 Bob Gibson Duluth Coachella Vly Won 2nd career; 1-0 score 29 1965 Jim -

Dflflflb SHOP TONIGHT to 9

•• THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. Friday. September C-4 ——— a. issv MAJOR LEAGUE BOX SCORES Braves' Pitching Gives fowler Denies CARDS, 10; BRAVES, 1 PIRAfES, 4; GIANTS, 2 DODGERS, 3; PHILUES, 1 Cardinals New Hope Quit NewYark A.H.O.A. P’abarib A.iXJA. Brook Ira A.H.O.A. Phils. AJi.O.A. Continued From Fsge C-l Don Hoak’a two-run double Plans to Clmoll.cf 4 (I * u Ashb'rn.cf 3 2 19 Torre.lb 4 1 13 O Derk.te 6 10 4 Mueßertrl fits VtoS&'cf !8 8 Reese.lib 4 II 0 3 Repuakl.rl 4 9 4 0 and Del Ennis accounted for In the second and Prank Robin- Sept 0 SPARTANBURG, S. C.. Valo.ll 3 0 8 B'chce.lb 4 16 1 two runs with his 19th homer son's 24th home run in the sSys lAnsor‘s.U 9 0 10 Lopatt.c 4 18 0 6 (fl.—Pitcher Art Fowler, sold ?}»sssef m Hodtea.lb 4 1 119 481mmons O o o 9 in the sixth. Then the Cards > third gave Brooks Lawrence ssasir" i 11J 8 »i Furlllo.rf 4 3 8 0 And'aon.U 4 o 1 9 bagged five in the eighth- all he needed for his 14th vic- by Cincinnati to Seattle of the ? 8 ? S La’Srith.r ¦: ? Neal.as il 14 Ha'ner.2b 4 12 3 2 f pitiP0 Douilaa.p 0 0 0 Walker.e 4 14 0 Kas’tkl.3b 4 1 4 0 three on A1 Dark’s pop fly tory although the Redlegs were League, denied W'xton.D 110 4 Pacific Coast ljthodaa inn o paca.p 0 0 0 u Zlm er.2b 3 0 3 2 Per'det.ss 3 0 11 out bit, Dick assss-'sss10 i IK t SS3 M’aant.p 0 0 0 0 Braklne.p 3 0 0 1 Roberts.p 2 0 12 double—for a 13-hit total I 7-6. -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist 1 Hoyt Wilhelm 2 Alvin Dark 3 Joe Coleman 4 Eddie Waitkus 5 Jim Robertson 6 Pete Suder 7 Gene Baker 8 Warren Hacker 9 Gil McDougald 10 Phil Rizzuto 11 Bill Bruton 12 Andy Pafko 13 Clyde Vollmer 14 Gus Keriazakos 15 Frank Sullivan 16 Jimmy Piersall 17 Del Ennis 18 Stan Lopata 19 Bobby Avila 20 Al Smith 21 Don Hoak 22 Roy Campanella 23 Al Kaline 24 Al Aber 25 Minnie Minoso 26 Virgil Trucks 27 Preston Ward 28 Dick Cole 29 Red Schoendienst 30 Bill Sarni 31 Johnny TemRookie Card 32 Wally Post 33 Nellie Fox 34 Clint Courtney 35 Bill Tuttle 36 Wayne Belardi 37 Pee Wee Reese 38 Early Wynn 39 Bob Darnell 40 Vic Wertz 41 Mel Clark 42 Bob Greenwood 43 Bob Buhl Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Danny O'Connell 45 Tom Umphlett 46 Mickey Vernon 47 Sammy White 48 (a) Milt BollingFrank Bolling on Back 48 (b) Milt BollingMilt Bolling on Back 49 Jim Greengrass 50 Hobie Landrith 51 El Tappe Elvin Tappe on Card 52 Hal Rice 53 Alex Kellner 54 Don Bollweg 55 Cal Abrams 56 Billy Cox 57 Bob Friend 58 Frank Thomas 59 Whitey Ford 60 Enos Slaughter 61 Paul LaPalme 62 Royce Lint 63 Irv Noren 64 Curt Simmons 65 Don ZimmeRookie Card 66 George Shuba 67 Don Larsen 68 Elston HowRookie Card 69 Billy Hunter 70 Lew Burdette 71 Dave Jolly 72 Chet Nichols 73 Eddie Yost 74 Jerry Snyder 75 Brooks LawRookie Card 76 Tom Poholsky 77 Jim McDonald 78 Gil Coan 79 Willy MiranWillie Miranda on Card 80 Lou Limmer 81 Bobby Morgan 82 Lee Walls 83 Max Surkont 84 George Freese 85 Cass Michaels 86 Ted Gray 87 Randy Jackson 88 Steve Bilko 89 Lou -

Ba Mss 121 Bl-587.69 – Bl-593.69

Collection Number BA MSS 121 BL-587.69 – BL-593.69 Title Tom Meany Scorebooks Inclusive Dates 1947 – 1963 NY teams Access By appointment during regular hours, email [email protected]. Abstract These scorebooks have scored games from spring training, All-Star games, and World Series games, and a few regular season games. Volume 1 has Jackie Robinson’s first game, April 15, 1947. Biography Tom Meany was recruited to write for the new Brooklyn edition of the New York Journal in 1922. The following year he earned a byline in the Brooklyn Daily Times as he covered the Dodgers. Over the years, Meany's sports writing career saw stops at numerous papers including the New York Telegram (later the World-Telegram), New York Star, Morning Telegraph, as well as magazines such as PM and Collier's. Following his sports writing career, Meany joined the Yankees in 1958. In 1961 he joined the expansion Mets as publicity director and later served as promotions director before his untimely death in 1964 at the age of 60. He received the Spink Award in 1975. Source: www.baseballhall.org Content List Volume 1 BL-587.69 1947 - Spring training, season games April 15, Jackie Robinson’s first game World Series - Dodgers v. Yankees 1948 - Spring training Volume 2 BL-588.69 1948 – Season games World Series, Indians vs. Braves 1962 - World Series, Giants vs. Yankees Volume 3 BL-589.69 1949 -Spring training, season games 1950 - May, Jul 11 All-Star game World Series, Yankees vs. Phillies 1951 - Playoff games, Dodgers vs. Giants World Series, Giants vs. -

Postseaason Sta Rec Ats & Caps & Re S, Li Ecord Ne S Ds

Postseason Recaps, Line Scores, Stats & Records World Champions 1955 World Champions For the Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1955 World Series was not just a chance to win a championship, but an opportunity to avenge five previous World Series failures at the hands of their chief rivals, the New York Yankees. Even with their ace Don Newcombe on the mound, the Dodgers seemed to be doomed from the start, as three Yankee home runs set back Newcombe and the rest of the team in their opening 6-5 loss. Game 2 had the same result, as New York's southpaw Tommy Byrne held Brooklyn to five hits in a 4-2 victory. With the Series heading back to Brooklyn, Johnny Podres was given the start for Game 3. The Dodger lefty stymied the Yankees' offense over the first seven innings by allowing one run on four hits en route to an 8-3 victory. Podres gave the Dodger faithful a hint as to what lay ahead in the series with his complete-game, six-strikeout performance. Game 4 at Ebbets Field turned out to be an all-out slugfest. After falling behind early, 3-1, the Dodgers used the long ball to knot up the series. Future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella and Duke Snider each homered and Gil Hodges collected three of the club’s 14 hits, including a home run in the 8-5 triumph. Snider's third and fourth home runs of the Series provided the support needed for rookie Roger Craig and the Dodgers took Game 5 by a score of 5-3.