Africat Hobatere Lion Research Project (Ahlrp) Update 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Ecology and Distribution of Lions in the Kunene and Erongo Regions, Namibia

Population ecology and distribution of lions in the Kunene and Erongo Regions, Namibia. June 2004 Dr. P. Stander 16 June 2004 Lions in the arid to semi-arid environment of the Kunene Region live at low densities and maintain large home ranges. In a classic example of adaptation to a harsh environment these lions exhibit unique behaviour, such as individual specialisation and cooperative hunting in Etosha (Stander 1992) and killing seals along the Skeleton Coast (Bridgeford 1985). Lions are of great aesthetic appeal and financial value due to the growing tourism industry in the Region. Baseline data on density, demography, and ecology of lions collected by this study contribute to our understanding of lion population dynamics and conservation status. These data are valuable and may be used to guide tourism development, management, and the development of long-term conservation strategies. INTENSIVE STUDY AREA The study site of 15 440 km2 is situated in the Palmwag Tourism Concession and extends into the Skeleton Coast Park and surrounding communal conservancies of the Kunene Region. The area falls in the Etendeka Plateau landscape of the northern Namib Desert, with an annual rainfall of 0 - 100 mm (Mendelsohn et al. 2002). The study area stretches from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the edge of human settlement and livestock farming in the east. The Hoaruseb river runs along the northern boundary and Springbok river in the south. Skeleton Coast Park Etosha Hoar useb National river Park Hoanib river Kunene Study Area Low density High density study area study area % Palmwag Uniab # river Namibia Lion population ecology in Kunene and Erongo Regions – June 2004 P Stander METHODS Lions in the Kunene are difficult to locate and observe. -

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa Camelopardalis Ssp

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. angolensis) Appendix 1: Historical and recent geographic range and population of Angolan Giraffe G. c. angolensis Geographic Range ANGOLA Historical range in Angola Giraffe formerly occurred in the mopane and acacia savannas of southern Angola (East 1999). According to Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo (2005), the historic distribution of the species presented a discontinuous range with two, reputedly separated, populations. The western-most population extended from the upper course of the Curoca River through Otchinjau to the banks of the Kunene (synonymous Cunene) River, and through Cuamato and the Mupa area further north (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). The intention of protecting this western population of G. c. angolensis, led to the proclamation of Mupa National Park (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). The eastern population occurred between the Cuito and Cuando Rivers, with larger numbers of records from the southeast corner of the former Mucusso Game Reserve (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). By the late 1990s Giraffe were assumed to be extinct in Angola (East 1999). According to Kuedikuenda and Xavier (2009), a small population of Angolan Giraffe may still occur in Mupa National Park; however, no census data exist to substantiate this claim. As the Park was ravaged by poachers and refugees, it was generally accepted that Giraffe were locally extinct until recent re-introductions into southern Angola from Namibia (Kissama Foundation 2015, East 1999, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). BOTSWANA Current range in Botswana Recent genetic analyses have revealed that the population of Giraffe in the Central Kalahari and Khutse Game Reserves in central Botswana is from the subspecies G. -

Management and Reproduction of the African Savanna Buffalo (Syncerus Caffer Caffer)

Management and reproduction of the African savanna buffalo (Syncerus caffer caffer) by Walter Ralph Hildebrandt Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Sciences in Animal Science at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Prof. Louw Hoffman Co-supervisor: Dr. Alison Leslie Faculty of Agricultural Science Department of Animal Science March 2014 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2014 Signature Date signed Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank and acknowledge my heavenly Father without Whom nothing would be possible. Furthermore I would like to thank the following individuals and institutions for support and guidance: Professor Louw Hoffman, Department of Animal Science, University of Stellenbosch, Dr. Alison Leslie, Department of Conservation Ecology, University of Stellenbosch, Mrs. Gail Jordaan, Department of Animal Science, University of Stellenbosch, Mrs. Zahn Munch, Department of Geology, University of Stellenbosch, The buffalo farmers that provided the necessary data, Mr. Craig Shepstone for technical and moral support and supplying much needed info regarding the game feeding, Staff members and post graduate students at the Department of Animal Science: Ms. -

Zambezi After Breakfast, We Follow the Route of the Okavango River Into the Zambezi Where Applicable, 24Hrs Medical Evacuation Insurance Region

SOAN-CZ | Windhoek to Kasane | Scheduled Guided Tour Day 1 | Tuesday 16 ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK 30 Group size Oshakati Ondangwa Departing Windhoek we travel north through extensive cattle farming areas GROUP DAY Katima Mulilo and bushland to the Etosha National Park, famous for its vast amount of Classic: 2 - 16 guests per vehicle CLASSIC TOURING SIZE FREESELL Opuwo Rundu Kasane wildlife and unique landscape. In the late afternoon, once we have reached ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK BWABWATA NATIONAL our camp located on the outside of the National Park, we have the rest of the PARK Departure details Tsumeb day at leisure. Outjo Overnight at Mokuti Etosha Lodge. Language: Bilingual - German and English Otavi Departure Days: Otjiwarongo Day 2 | Wednesday Tour Language: Bilingual DAMARALAND ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK Okahandja The day is devoted purely to the abundant wildlife found in the Etosha Departure days: TUESDAYS National Park, which surrounds a parched salt desert known as the Etosha Gobabis November 17 Pan. The park is home to 4 of the Big Five - elephant, lion, leopard and rhino. 2020 December 1, 15 WINDHOEK Swakopmund Game viewing in the park is primarily focussed around the waterholes, some January 19 of which are spring-fed and some supplied from a borehole, ideal places to February 16 Walvis Bay Rehoboth sit and watch over 114 different game species, or for an avid birder, more than March 2,16,30 340 bird species. An extensive network of roads links the over 30 water holes April 13 SOSSUSVLEI Mariental allowing visitors the opportunity of a comprehensive game viewing safari May 11, 25 throughout the park as each different area will provide various encounters. -

National Parks of Namibia.Pdf

Namibia’s National Parks “Our national parks are one of Namibia’s most valuable assets. They are our national treasures and their tourism potential should be harnessed for the benefi t of all people.” His Excellency Hifi kepunye Pohamba Republic of Namibia President of the Republic of Namibia Ministry of Environment and Tourism Exploring Namibia’s natural treasures Sparsely populated and covering a vast area of 823 680 km2, roughly three times the size of the United King- dom, Namibia is unquestionably one of Africa’s premier nature tourism destinations. There is also no doubt that the Ministry of Environment and Tourism is custodian to some of the biggest, oldest and most spectacular parks on our planet. Despite being the most arid country in sub-Saharan Af- rica, the range of habitats is incredibly diverse. Visitors can expect to encounter coastal lagoons dense with flamingos, towering sand-dunes, and volcanic plains carpeted with spring flowers, thick forests teeming with seasonal elephant herds up to 1 000 strong and lush sub-tropical wetlands that are home to crocodile, hippopotami and buffalo. The national protected area network of the Ministry of Environment and Tourism covers 140 394 km2, 17 per cent of the country, and while the century-old Etosha National and Namib-Naukluft parks are deservedly re- garded as the flagships of Namibia’s conservation suc- cess, all the country’s protected areas have something unique to offer. The formidable Waterberg Plateau holds on its summit an ecological ‘lost world’ cut off by geology from its surrounding plains for millennia. The Fish River Canyon is Africa’s grandest, second in size only to the American Grand Canyon. -

7 Day Namibia Highlights – Etosha - Sossusvlei Sossusvlei - Swakopmund - Etosha National Park - Windhoek 7 Days / 6 Nights Minimum: 2 Pax Maximum: 18 Pax

Page | 1 7 Day Namibia Highlights – Etosha - Sossusvlei Sossusvlei - Swakopmund - Etosha National Park - Windhoek 7 Days / 6 Nights Minimum: 2 Pax Maximum: 18 Pax TOUR OVERVIEW Start Accommodation Destination Basis Room Type Duration Day 1 Sossusvlei Lodge or similar Sossusvlei D,B&B 1x Standard Twin 2 Nights Room Day 3 Swakopmund Sands Hotel Swakopmund B&B 1x Standard Twin 2 Nights Room Day 5 Okaukuejo Resort Etosha South D,B&B 1x Standard Twin 1 Night Room Day 6 Namutoni Resort Etosha East D,B&B 1x Standard Twin 1 Night Room MEERCAT SAFARIS VAT # 778169-01-1 [email protected] Katatura, Windhoek REG # CC/2016/01956 +264 81 329 5790 / 85 662 6014 NTB # TSO 01180 Page | 2 Key B&B: Bed and Breakfast D,B&B: Dinner, Bed and Breakfast Price 01 November 2021- 30 June 2022 N$24 300.00 per person sharing N$ 6 790.00 single supplement 01 July 2022 – 30 October 2022 N$25 420.00 per person sharing N$ 8 980.00 single supplement Included 1. Pick up from Windhoek accommodation 2. Standard Information package 3. Professional English speaking tour guide 4. Accommodation as per itinerary 5. Meals as per itinerary 6. Activities as per itinerary 7. Drop off at Windhoek accommodation Excluded 1. Beverages (Alcoholic, soft drinks & bottled water) 2. Other meals not specified 3. Personal Travel insurance 4. Other optional activities 5. Tour guide tips and gratuities 6. Visa’s 7. Flights 8. Items of personal nature Day 1: Sossusvlei Lodge, Sossusvlei MEERCAT SAFARIS VAT # 778169-01-1 [email protected] Katatura, Windhoek REG # CC/2016/01956 +264 81 329 5790 / 85 662 6014 NTB # TSO 01180 Page | 3 Located in southwestern Africa, Namibia boasts a well-developed infrastructure, some of the best tourist facilities in Africa, and an impressive list of breathtaking natural wonders. -

Basingstoke Local Group

BBAASSIINNGGSSTTOOKKEE LLOOCCAALL GGRROOUUPP DECEMBER 2015 NEWSLETTER http://www.rspb.org.uk/groups/basingstoke Contents: From The Group Leader Notices What’s Happening? December’s Outdoor Meeting January’s Outdoor Meeting November’s Outdoor Meeting Namibia: To Hobatere For Mountain Zebras, Mountain Squirrels … And… “Mountain Giraffes”? Local Wildlife News Quiz Page And Finally! Charity registered in England and Wales no. 207076 From The Group Leader Welcome to the December, dare I say Christmas Newsletter! Now that the winter's truly with us, as those attending recent walks will attest to, it's surely time to once again look forward to the coming year, the meetings to attend, the wildlife to look for and enjoy, both within the presentations and out in the field, and all that the RSPB and Britain can offer. We're all very fortunate in that we live in the latter and that we have the former protecting so many areas, with our help, for wildlife, both for now and, hopefully, the future. Hopefully, once again, we'll all get the opportunity to make the most of the special sites under the protection of the Society, some of which the Local Group will be visiting, both locally and further afield on forays to Norfolk etc. in the coming year. Yet again earlier this year the Local Group placed a donation with the HQ to help with work on these sites, so if you do visit any of the c.200 reserves please do remember that your generosity continues to help maintain these, and of course the wildlife that flourishes on them; perhaps you paid for those reeds that the ‘pinging’ Bearded Tit you’re trying to watch are remaining all too elusive in! At the AGM earlier this year the Treasurer, Gerry, explained about changes that we thought ought to be brought in with regard to the annual donation, primarily the way in which such monies would be raised in the future. -

Namibia & the Okavango

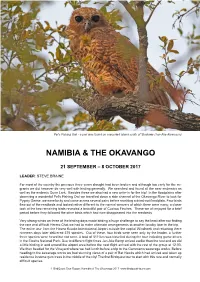

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

05 Night Namib Desert & Etosha National Park

05 NIGHT NAMIB DESERT & ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK This tour is for those who want to experience two of Namibia´s main attractions in the shortest possible time – The Namib Desert and the Etosha National Park. INFORMATION Sossusvlei Located in the scenic Namib-Naukluft National Park, Sossusvlei is where you will find the iconic red sand dunes of the Namib. The clear blue skies contrast with the giant red dunes to make this one of the most scenic natural wonders of Africa and a photographer's heaven. This awe-inspiring destination is possibly Namibia's premier attraction, with its unique dunes rising to almost 400 metres- some of the highest in the world. These iconic dunes come alive in morning and evening light and draw photography enthusiasts from around the globe. Sossusvlei is home to a variety desert wildlife including oryx, springbok, ostrich and a variety of reptiles. Visitors can climb 'Big Daddy', one of Sossusvlei’s tallest dunes; explore Deadvlei, a white, salt, claypan dotted with ancient trees; or for the more extravagant, scenic flights and hot air ballooning are on offer, followed by a once-in-a-lifetime champagne breakfast amidst these majestic dunes. Namib-Naukluft National Park Stretching almost 50000 square kilometres across the red-orange sands of the Namib Desert over the Naukluft Mountains to the east, the Namib-Naukluft National Park is Africa’s biggest wildlife reserve and the fourth largest in the world. Despite the unforgiving conditions, it is inhabited by a plethora of desert-adapted animals, including reptiles, buck, hyenas, jackals, insects and a variety of bird species. -

S P E C I E S S U R V I V a L C O M M I S S I

ISSN 1026 2881 Journal of the African Elephant, African Rhino and Asian Rhino Specialist Groups January–June 2011 No. 49 1 Chair reports/Rapports des Présidents 1 African Elephant Specialist Group report/Rapport du S p e c i e s Groupe Spécialiste des Eléphants d’Afrique S u r v i v a l Holly T. Dublin C o m m i s s i o n Editor 6 African Rhino Specialist Group report/Rapport du Bridget McGraw Groupe Spécialiste des Rhinos d’Afrique Section Editors Deborah Gibson—African elephants Mike Knight Kees Rookmaaker—African and Asian rhinos Editorial Board 16 Asian Rhino Specialist Group report/Rapport du Julian Blanc Groupe Spécialiste du Rhinocéros d’Asie Holly T. Dublin Richard Emslie Bibhab Kumar Talukdar Mike Knight Esmond Martin Robert Olivier 20 Research Diane Skinner 20 Matriarchal associations and reproduction in a Bibhab K. Talukdar remnant subpopulation of desert-dwelling elephants Lucy Vigne in Namibia Design and layout Keith E.A. Leggett, Laura MacAlister Brown and Aksent Ltd Rob Roy Ramey II Address all correspondence, including enquiries about subscription, to: 33 Invasive species in grassland habitat: an ecological The Editor, Pachyderm threat to the greater one-horned rhino (Rhinoceros PO Box 68200–00200 unicornis) Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 249 3561/65 Bibhuti P. Lahkar, Bibhab Kumar Talukdar and Cell:+254 724 256 804/734 768 770 email: [email protected] Pranjit Sarma website: http://pachydermjournal.org Reproduction of this publicaton for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. -

Luxury Namibian Desert Dunes Safari

P a g e | 1 Luxury Namibian Desert Dunes Safari P a g e | 2 Luxury Namibian Desert Dunes Safari Sossusvlei - Swakopmund - Skeleton Coast - Palmwag 10 Days / 9 Nights Date of Issue: 12 January 2018 Click here to view your Digital Itinerary Overview Accommodation Destination Nights Basis Room Type Kulala Desert Lodge Sossusvlei 2 FI Hansa Hotel Swakopmund 2 FI Terrace Bay Resort Skeleton Coast 1 FI Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp Skeleton Coast 2 FI Desert Rhino Camp Palmwag 2 FI Key FI: Fully inclusive Price From USD 6,000 per person P a g e | 3 Day 1: Kulala Desert Lodge, Sossusvlei Day Itinerary From Windhoek we drive to Kulala Desert Lodge in the private Kulala Wilderness Reserve. Here we explore the iconic dunes of Sossusvlei and the moon-like landscape of Dead Vlei. Sossusvlei Located in the scenic Namib-Naukluft National Park, Sossusvlei is where you will find the iconic red sand dunes of the Namib. The clear blue skies contrast with the giant red dunes to make this one of the most scenic natural wonders of Africa and a photographer's heaven. This awe-inspiring destination is possibly Namibia's premier attraction, with its unique dunes rising to almost 400 metres-some of the highest in the world. These iconic dunes come alive in morning and evening light and draw photography enthusiasts from around the globe. Sossusvlei is home to a variety desert wildlife including oryx, springbok, ostrich and a variety of reptiles. Visitors can climb 'Big Daddy', one of Sossusvlei’s tallest dunes; explore Deadvlei, a white, salt, claypan dotted with ancient trees; or for the more extravagant, scenic flights and hot air ballooning are on offer, followed by a once-in-a-lifetime champagne breakfast amidst these majestic dunes. -

Jobs, Game Meat and Profits: the Benefits of Wildlife Ranching on Marginal Lands in South Africa

Jobs, game meat and profits: The benefits of wildlife ranching on marginal lands in South Africa W. Andrew Taylora,b, Peter A. Lindseyc,d,e, Samantha K. Nicholsona, Claire Reltona and Harriet T. Davies-Mosterta,c aThe Endangered Wildlife Trust, 27 & 28 Austin Road, Glen Austin AH, Midrand 1685, Gauteng, South Africa bCentre for Veterinary Wildlife Studies, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa cMammal Research Institute, Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa dEnvironmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan, QLD 4222, Australia eWildlife Conservation Network, 209 Mississippi Street, San Francisco, USA *Corresponding author at: The Endangered Wildlife Trust, 27 & 28 Austin Road, Glen Austin AH, Midrand 1685, Gauteng, South Africa. Email: [email protected] Highlights x 80% of private wildlife properties in South Africa conduct consumptive land uses x Intensive breeding covers 5% of the total land area of private wildlife properties x Profitability is highly variable between properties, with an average ROI of 0.068 x Wildlife properties employ more people per unit area than livestock farms x The private wildlife sector is a financially sustainable land use option on marginal land Abstract The private wildlife sector in South Africa must demonstrate value in the face of political pressures for economic growth, job creation and food security. Through structured survey questionnaires of landowners and managers from 276 private wildlife ranches, we describe patterns of wildlife-based land uses (WBLUs), estimate their financial and social contributions and compare these with livestock farming. We show that 46% of surveyed properties combined wildlife with livestock, 86% conducted two or more WBLUs and 80% conducted consumptive use activities.