The Chumash: How Do Migratory Patterns in SW California Reflect Centralised Control?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Coast Bike Tour Monterey, Carmel, Big Sur, and Santa Barbara: Cycling the Iconic Central Coast

+1 888 396 5383 617 776 4441 [email protected] DUVINE.COM United States / California / Central Coast California Coast Bike Tour Monterey, Carmel, Big Sur, and Santa Barbara: Cycling the Iconic Central Coast © 2021 DuVine Adventure + Cycling Co. Bike the entire length of California’s Big Sur coastline and cover some of the most spectacular coastal roads in the world Savor fresh seafood, farm-to-table fare, and flaky pastries at the hippest restaurants, hidden bistros, and charming bakeries Experience Central Coast luxury at hotels and inns in ideal locations lining the way from dramatic Carmel-by-the-Sea to country-chic Los Olivos Taste wine where it’s produced in the Santa Ynez Valley—a region that’s coming to compete with California’s well-known Napa and Sonoma wine country Challenge yourself with a century ride that covers 100 miles of Pacific coastline from Big Sur to Morro Bay Arrival Details Departure Details Airport City: Airport City: San Francisco or San Jose, California Santa Barbara or Los Angeles, CA Pick-Up Location: Drop-Off Location: Stanford Park Hotel Downtown Santa Barbara Pick-Up Time: Drop-Off Time: 9:30 am 11:00 am NOTE: DuVine provides group transfers to and from the tour, within reason and in accordance with the pick-up and drop-off recommendations. In the event your train, flight, or other travel falls outside the recommended departure or arrival time or location, you may be responsible for extra costs incurred in arranging a separate transfer. Emergency Assistance For urgent assistance on your way to tour or while on tour, please always contact your guides first. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes Among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Kristina Marie Gill Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Glassow, Chair Professor Michael A. Jochim Professor Amber M. VanDerwarker Professor Lynn H. Gamble September 2015 The dissertation of Kristina Marie Gill is approved. __________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim __________________________________________ Amber M. VanDerwarker __________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble __________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow, Committee Chair July 2015 Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California Copyright © 2015 By Kristina Marie Gill iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my Family, Mike Glassow, and the Chumash People. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people who have provided guidance, encouragement, and support in my career as an archaeologist, and especially through my undergraduate and graduate studies. For those of whom I am unable to personally thank here, know that I deeply appreciate your support. First and foremost, I want to thank my chair Michael Glassow for his patience, enthusiasm, and encouragement during all aspects of this daunting project. I am also truly grateful to have had the opportunity to know, learn from, and work with my other committee members, Mike Jochim, Amber VanDerwarker, and Lynn Gamble. I cherish my various field experiences with them all on the Channel Islands and especially in southern Germany with Mike Jochim, whose worldly perspective I value deeply. I also thank Terry Jones, who provided me many undergraduate opportunities in California archaeology and encouraged me to attend a field school on San Clemente Island with Mark Raab and Andy Yatsko, an experience that left me captivated with the islands and their history. -

Domestic Champagne Sauvignon Blanc Aromatic Whites Chardonnay Pinot Noir Rhône Italian and Spanish Cabernet Sauvignon and Borde

RHÔNE 2011 Domaine La Ligière ‘Vacqueyras’ Grenache - Rhône Valley, France DOMESTIC 2012 Cypress Terrace Syrah - Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand 2015 Bloomer Creek ‘Tanzen Dame’ Pet’ Nat’ - Fingerlakes, New York 2011 Neyers ‘Evangelho Vineyard’ Mourvedre - St. Helena, California 2015 Schramsberg Blanc de Blancs - Calistoga, California 2016 Arnot-Roberts Syrah - Sonoma Coast, California 2015 Schramsberg Brut Rosé - Calistoga, California 2015 Jolie-Laide ‘Halcon Vineyard’ Syrah - Yorkville Highlands, California 2015 Jolie-Laide ‘Dry Creek Valley’ Grenache - Yorkville Highlands, California CHAMPAGNE NV Gonet-Médeville ‘Tradition’ Premier Cru - Mareuil-sur-Aÿ ITALIAN AND SPANISH NV Diebolt-Vallois ‘à Cramant’ Brut Rosé - Côte des Blancs 2016 Idlewild ‘The Bird’ Dolcetto - Mendocino Valley, California NV Bérêche et Fils ‘Les Beaux Regards’ - Ludes 2013 Vinca Minor ‘Rosewood Vineyards’ Carignan - Mendocino Valley, California 2014 Marco De Bartoli ‘Rosso Di Marco’ Pignatello - Sicily, Italy 2011 CVNE ‘Vina Real’ Gran Reserva - Rioja, Spain 2014 Renato Fenocchio ‘Rombone’ Barbaresco - Piedmont, Italy 2014 Ryme Cellars ‘Luna Mata’ Aglianico - Paso Robles, California SAUVIGNON BLANC 2013 Mocali Brunello di Montalcino - Tuscany, Italy 2015 Stonecrop ‘Dry River Road’ - Martinborough, New Zealand 2015 Cruse Wine Co. Tannat - Mendocino County, California 2017 Populis ‘Venturi Vineyard’ - Mendocino County, California 2013 Oddero ‘Villero’ Barolo - Piedmont, Italy 2016 Domaine Fleuriet et Fils Sancerre - Loire Valley, France 2013 Grieve ‘Lovall Valley’ - Napa, -

Federal Register/Vol. 71, No. 110/Thursday, June 8, 2006/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 71, No. 110 / Thursday, June 8, 2006 / Rules and Regulations 33239 request for an extension beyond the Background Background on Viticultural Areas maximum duration of the initial 12- The final regulations (TD 9254) that TTB Authority month program must be submitted are the subject of this correction are electronically in the Department of under section 1502 of the Internal Section 105(e) of the Federal Alcohol Homeland Security’s Student and Revenue Code. Administration Act (the FAA Act, 27 Exchange Visitor Information System U.S.C. 201 et seq.) requires that alcohol (SEVIS). Supporting documentation Need for Correction beverage labels provide consumers with must be submitted to the Department on As published, final regulations (TD adequate information regarding product the sponsor’s organizational letterhead 9254) contains an error that may prove identity and prohibits the use of and contain the following information: to be misleading and is in need of misleading information on such labels. (1) Au pair’s name, SEVIS clarification. The FAA Act also authorizes the identification number, date of birth, the Secretary of the Treasury to issue length of the extension period being Correction of Publication regulations to carry out its provisions. requested; Accordingly, the final regulations (TD The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and (2) Verification that the au pair 9254) which was the subject of FR Doc. Trade Bureau (TTB) administers these completed the educational requirements 06–2411, is corrected as follows: regulations. of the initial program; and On page 13009, column 2, in the Part 4 of the TTB regulations (27 CFR (3) Payment of the required non- preamble, under the paragraph heading part 4) allows the establishment of refundable fee (see 22 CFR 62.90) via ‘‘Special Analyses’’, line 4 from the definitive viticultural areas and the use Pay.gov. -

The Santa Ynez Valley Is a Year-Round Destination for Fun and Relaxation

The Santa Ynez Valley is a year-round destination for fun and relaxation. Each season is uniquely special, but we’re particularly fond of our fall. The perfect break between summer and winter, fall features a profusion of activities that the whole family can enjoy. Located in California’s northern Santa Barbara County, the Santa Ynez Valley is just 35 miles from the beaches of Santa Barbara, 125 miles up the coast from Los Angeles and 300 miles south of San Francisco. We offer rich autumn colors, small-town charm, California cuisine, and a surprising Danish history - all wrapped into one fabulous adventure. The six towns of Ballard, Buellton, Los Alamos, Los Olivos, Santa Ynez and Solvang are ready to welcome you in style for a fall Santa Ynez vacation. Fall temperatures range from the mid- 70s to 80s during the day, and comfortable high 40s to low 50s at night. Average precipitation is about an inch per month. Stop by our website at VisitSYV.com to review our complete listing of things to do in Santa Ynez Valley, Santa Ynez Valley restaurants, and Santa Ynez hotels and inns, or check out our suggestions below for the Top 25 fun things to do in the Santa Ynez Valley this fall. Enjoy Fall in the Santa Ynez Valley! (www.visitsyv.com) Top 25 Fun Fall Things to Do In The Santa Ynez Valley 1. The Wine is Always Fine: The Santa Ynez Valley produces some wonderful wines for your sipping pleasures. The grapes are ready, the vintners are producing their very best wines, and sampling is a must! The SYV is home to four distinct American Viticulture Areas (AVAs), which produce more than 1 million cases of wine each year. -

Arlington Springs Man”

“Arlington Springs Man” Resource Summary: Study guide questions for viewing the video with answer key, vocabulary worksheet relating to Santa Rosa Island, additional articles about the island and Arlington Springs Man, maps of the current and prehistoric island. Subject Areas: science, human geography Grade Level Range: 5-10 Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.9-10.2 Write informative/explanatory texts, including the narration of historical events, scientific procedures/ experiments, or technical processes. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.9-10.2.D Use precise language and domain-specific vocabulary to manage the complexity of the topic and convey a style appropriate to the discipline and context as well as to the expertise of likely readers. Resource Provided By: Lucy Carleton, English/ELD, Carpinteria High School, Carpinteria Unified School District Resource Details: “Arlington Springs Man” Running time 9 minutes. Cast: Dr. Jon Erlandson, archaeologist, University of Oregon Dr. John Johnson, curator of anthropology, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Don Morris, archaeologist Channel Islands national Park (retired) Phil Orr, (non speaking role) Curator of anthropology Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Study Guide “Arlington Springs Man” The West of the West 1. Define strata: 2. In what ways is Santa Rosa Island just like a layer cake? 3. Why is Santa Rosa Island such a perfect place for archaeologists and geologists to study? 4. What caused the formation of the prehistoric mega-island Santarosae (Santa Rosae) and which of the current Channel Islands were part of it? 5. How far can a modern-day elephant swim? What can you conclude about how mammoths arrived to the islands? 6. -

Contributions by Employer

2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT HOME / CAMPAIGN FINANCE REPORTS AND DATA / PRESIDENTIAL REPORTS / 2008 APRIL MONTHLY / REPORT FOR C00431569 / CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT PO Box 101436 Arlington, Virginia 22210 FEC Committee ID #: C00431569 This report contains activity for a Primary Election Report type: April Monthly This Report is an Amendment Filed 05/22/2008 EMPLOYER SUM NO EMPLOYER WAS SUPPLIED 6,724,037.59 (N,P) ENERGY, INC. 800.00 (SELF) 500.00 (SELF) DOUGLASS & ASSOCI 200.00 - 175.00 1)SAN FRANCISCO PARATRAN 10.50 1-800-FLOWERS.COM 10.00 101 CASINO 187.65 115 R&P BEER 50.00 1199 NATIONAL BENEFIT FU 120.00 1199 SEIU 210.00 1199SEIU BENEFIT FUNDS 45.00 11I NETWORKS INC 500.00 11TH HOUR PRODUCTIONS, L 250.00 1291/2 JAZZ GRILLE 400.00 15 WEST REALTY ASSOCIATES 250.00 1730 CORP. 140.00 1800FLOWERS.COM 100.00 1ST FRANKLIN FINANCIAL 210.00 20 CENTURY FOX TELEVISIO 150.00 20TH CENTURY FOX 250.00 20TH CENTURY FOX FILM CO 50.00 20TH TELEVISION (FOX) 349.15 21ST CENTURY 100.00 24 SEVEN INC 500.00 24SEVEN INC 100.00 3 KIDS TICKETS INC 121.00 3 VILLAGE CENTRAL SCHOOL 250.00 3000BC 205.00 312 WEST 58TH CORP 2,000.00 321 MANAGEMENT 150.00 321 THEATRICAL MGT 100.00 http://docquery.fec.gov/pres/2008/M4/C00431569/A_EMPLOYER_C00431569.html 1/336 2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT 333 WEST END TENANTS COR 100.00 360 PICTURES 150.00 3B MANUFACTURING 70.00 3D INVESTMENTS 50.00 3D LEADERSHIP, LLC 50.00 3H TECHNOLOGY 100.00 3M 629.18 3M COMPANY 550.00 4-C (SOCIAL SERVICE AGEN 100.00 402EIGHT AVE CORP 2,500.00 47 PICTURES, INC. -

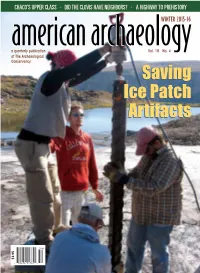

Saving Ice Patch Artifacts Saving Ice Patch Artifacts

CHACO’S UPPER CLASS • DID THE CLOVIS HAVE NEIGHBORS? • A HIGHWAY TO PREHISTORY american archaeologyWINTER 2015-16 americana quarterly publication archaeology Vol. 19 No. 4 of The Archaeological Conservancy SavingSaving IceIce PatchPatch ArtifactsArtifacts $3.95 american archaeologyWINTER 2015-16 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 19 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 12 ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE ICE PATCHES BY TAMARA STEWART Archaeologists are racing to preserve fragile artifacts that are exposed when ice patches melt. 19 THE ROAD TO PREHISTORY BY ELIZABETH LUNDAY A highway-expansion project in Texas led to the discovery of several ancient Caddo sites and raised issues about preservation. 26 CHACO’S UPPER CLASS EE L BY CHARLES C. POLING New research suggests an elite class emerged at RAIG C / Chaco Canyon much earlier than previously thought. AAR NST 32 DID THE CLOVIS PEOPLE HAVE NEIGHBORS? I 12 BY MARCIA HILL GOSSARD Discoveries from the Cooper’s Ferry site indicate that two different cultures inhabited North America 44 new acquisition roughly 13,000 years ago. CONSERVANCY ACQUIRES A PORTION OF MANZANARES PUEBLO IN NEW MEXICO 38 LIFE ON THE NORTHERN FRONTIER Manzanares is one of the sites included in the Galisteo BY WAYNE CURTIS Basin Archaeological Sites Protection Act. Researchers are trying to understand what life was like at an English settlement in southern Maine around 46 new acquisition the turn of the 18th century. DONATION OF TOWN SQUARE BANK MOUND UNITES LOCAL COMMUNITY Various people played a role in the Conservancy’s 19 acquisition of a prehistoric mound. 47 point acquisition A LONG TIME COMING The Conservancy waited for 20 years to acquire T the Dingfelder Circle. -

Burro Flats Cultural District NRHP Nomination

Exhibit 2 – Burro Flats Cultural District NRHP Nomination NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Burro Flats Cultural District__(Public Version) ____________________ Other names/site number: ___________________________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ___N/A___________________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __5800 Woolsey Canyon Road (Santa Susanna Field Laboratory)________ City or town: _Canoga Park__ State: _California_ County: _Ventura_ Not For Publication: Vicinity: X X ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination -

Charles Lindbergh's Contribution to Aerial Archaeology

THE FATES OF ANCIENT REMAINS • SUMMER TRAVEL • SPANISH-INDIGENOUS RELIGIOUS HARMONY american archaeologySUMMER 2017 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 21 No. 2 Charles Lindbergh’s Contribution To Aerial Archaeology $3.95 US/$5.95 CAN summer 2017 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 21 No. 2 COVER FEATURE 18 CHARLES LINDBERGH’S LITTLE-KNOWN PASSION BY TAMARA JAGER STEWART The famous aviator made important contributions to aerial archaeology. 12 COMITY IN THE CAVES BY JULIAN SMITH Sixteenth-century inscriptions found in caves on Mona Island in the Caribbean suggest that the Spanish respected the natives’ religious expressions. 26 A TOUR OF CIVIL WAR BATTLEFIELDS BY PAULA NEELY ON S These sites serve as a reminder of this crucial moment in America’s history. E SAM C LI A 35 CURING THE CURATION PROBLEM BY TOM KOPPEL The Sustainable Archaeology project in Ontario, Canada, endeavors to preserve and share the province’s cultural heritage. JAGO COOPER AND 12 41 THE FATES OF VERY ANCIENT REMAINS BY MIKE TONER Only a few sets of human remains over 8,000 years old have been discovered in America. What becomes of these remains can vary dramatically from one case to the next. 47 THE POINT-6 PROGRAM BEGINS 48 new acquisition THAT PLACE CALLED HOME OR Dahinda Meda protected Terrarium’s remarkable C E cultural resources for decades. Now the Y S Y Conservancy will continue his work. DD 26 BU 2 LAY OF THE LAND 3 LETTERS 50 FiELD NOTES 52 REVIEWS 54 EXPEDITIONS 5 EVENTS 7 IN THE NEWS COVER: In 1929, Charles and Anne Lindbergh photographed Pueblo • Humans In California 130,000 Years Ago? del Arroyo, a great house in Chaco Canyon. -

Big Sur Road Bike Tour

CALIFORNIA BIG SUR ROAD BIKE TOUR A highly influential, early 20th century watercolorist and muralist, Francis McComas defined California’s Central Coast Big Sur as “the greatest meeting of land sea.” With that visionary exactness as our guide, we shaped a virtuoso velo interpretation of the Golden State’s Central Coast: animated as much by sea cliffs and rolling wine country, iconic Highway One to Redwoods, breaching Gray whales to far more furtive sea otters. The same confluence of unique, wild character lured Henry Miller, Jack Kerouac, The Beats, if not an untold number of artists, such as the aforementioned McComas. From the burly rawness of Big Sur to the Mediterranean-like aesthetic seen in Santa Barbara’s coastline—aka the American Riviera—our big brushstrokes in the saddle sweep past ranch, farmland if not great spans of ocean. At the same time, a dreamy, viscous, essentially California-quality light outlines each successive landscape. Each day’s epic resolves into equally sublime soft-notes and local-regional qualities. From clam chowder in Pismo Beach to Pinot Noir in Monterrey, groves of wind-sculpted Cypress on 17-Mile Drive, historic lighthouses to the Heart Castle. Closing out on a different type of replenishment, at every setting we contemplate and savor superb regional cuisine shaped by a fulsome farm-to-table ethos.P a g e | 1 800-596-2953 | www.escapeadventures.com | Open 7 Days As we collectively inhale this landscape, Smith Rock—the birthplace of modern rock-climbing—ultimately takes our breath away; projecting lengthy silhouettes, from its cathedral like spikes and pinnacles onto an already staggering sunset. -

Burro Flats Cultural Distric

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Burro Flats Cultural District__(Public Version) _DRAFT______________ Other names/site number: ___________________________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ___N/A___________________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __5800 Woolsey Canyon Road (Santa Susanna Field Laboratory)________ City or town: _Canoga Park__ State: _California_ County: _Ventura_ Not For Publication: Vicinity: X X ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation