No 1 Leenaun to Clonbur Through Joyce Country There Are Roads For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land League (1879-82)

Oughterard and Kilannin: The Land League (1879-82) Please check the following page(s) for clarification. Issues are highlighted in [red] in the transcribed text. Michael Davitt (1846-1906) Davitt, founder of the Land League, was the son of an evicted Mayo tenant. He was imprisoned for fifteen years in 1870 on charges of Fenian conspiracy in England. Released from Dartmoor prison in 1877 on ‘ticket of leave’, he returned to Ireland. He staged a mass meeting at Irishtown, Co. Mayo, on 20th April, 1879. This demonstration was called to protest against excessive rents and was attended by over 10,000. Other large meetings followed and the movement quickly spread from Mayo to Connaught and then throughout the country. The Irish National Land League was founded in Dublin on 21st October, 1879, with C. S. Parnell as its president. The objects of the Land League were 1) to reduce rack rents and 2) to obtain the ownership of the soil by its occupiers, i.e. tenant ownership. During the Land War (1879-82), Davitt wrote that the landlords were “a brood of cormorant vampires that has sucked the life blood out of the country.” The Land League was a non-violent mass movement but it used the methods of publicity, moral intimidation and boycott against landlords and land grabbers who broke the Land League code. This popular movement achieved a remarkable degree of success. Within a generation of its founding, by the early 20th century, most of the tenant farmers of Ireland had become owners of their farms and the landlord system, which had dominated Ireland for centuries, had been ended. -

Visit Louth Brochure

About County Louth • 1 hour commute from Dublin or Belfast; • Heritage county, steeped in history with outstanding archaeological features; • Internationally important and protected coastline with an unspoiled natural environment; • Blue flag beaches with picturesque coastal villages at Visit Louth Baltray, Annagassan, Clogherhead and Blackrock; • Foodie destination with award winning local produce, Land of Legends delicious fresh seafood, and an artisan food and drinks culture. and Full of Life • ‘sea louth’ scenic seafood trail captures what’s best about Co. Louth’s coastline; the stunning scenery and of course the finest seafood. Whether you visit the piers and see where the daily catch is landed, eat the freshest seafood in one of our restaurants or coastal food festivals, or admire the stunning lough views on the greenway, there is much to see, eat & admire on your trip to Co. Louth • Vibrant towns of Dundalk, Drogheda, Carlingford and Ardee with nationally-acclaimed arts, crafts, culture and festivals, museums and galleries, historic houses and gardens; • Easy access to adventure tourism, walking and cycling, equestrian and water activities, golf and angling; • Welcoming hospitable communities, proud of what Louth has to offer! Carlingford Tourist Office Old Railway Station, Carlingford Tel: +353 (0)42 9419692 [email protected] | [email protected] Drogheda Tourist Office The Tholsel, West St., Drogheda Tel: +353 (0)41 9872843 [email protected] Dundalk Tourist Office Market Square, Dundalk Tel: +353 (0)42 9352111 [email protected] Louth County Council, Dundalk, Co. Louth, Ireland Email: [email protected] Tel: +353 (0)42 9335457 Web: www.visitlouth.ie @VisitLouthIE @LouthTourism OLD MELLIFONT ABBEY Tullyallen, Drogheda, Co. -

HANDBRAKES & HAIRPINS Issue

HHandbrakesandbrakes airpins HHairpins g he world of rallyin & yyourour insightinsight intointo thet world of rallying CCoverover SSilkilk WWayay RRallyally 22010:010: DDaredevilaredevil ddrivers!rivers! IIssuessue 115151 • 2233 - 2299 SSeptept 22010010 hhttp://handbrakeshairpins.wordpress.comttp://handbrakeshairpins.wordpress.com FFeatureseatures NNewsews Breen aims for News from the win in BRC, P7 EEventsvents Swartland Rally Erika Detota SRC and BRC event wins in IRNY, P6 SARC,SARCA P10 news Block releases IRC,IR P14 WWRC and IRC new video, P8 newsne updates Contents / Issue 151 Editorial Information 04 News Editor Evan Rothman 06 Features Photojournalist Eva Kovkova Contributors RallyBuzz, Motorpics. 06 Detota wins IRNY 2WD class 07 Breen aims for win in Yorkshire 08 Block releases new GYMKHANA video All content copyrighted property of HANDBRAKES & HAIRPINS, 2007- 10 Events 10. This publication is fully protected by 10 Swartland Rally REVIEW copyright and nothing may be reprinted in 12 Silk Way Rally REVIEW, pt 2 whole or in part without written permission 14 IRC Rallye Sanremo PREVIEW from the editor. While reasonable 15 SRC C. McRae Forest Stages PREVIEW precautions have been taken to ensure the 16 Toyota Desert 1000 Race PREVIEW accuracy of information from sources and 17 BRC Int’l Rally Yorkshire PREVIEW given to readers, the editor cannot accept responsibility for any inconvenience or damage that may arise therefrom. Contact E-mail us [email protected] Welcome to H&H! Call us +27 83 452 6892 Welcome to issue 151 of HANDBRAKES & Surf us http://wp.me/pkXc HAIRPINS, your FREE weekly insight into the world of rallying. To receive your FREE weekly Many thanks for all the well wishes HANDBRAKES & HAIRPINS eMagazine, and congratulations on our 150th issue last or if you’d like to share this with a friend week. -

Mge0741rp0008

ADDENDUM TO EDGE 2D HR SEISMIC SURVEY AND SITE SURVEY – SCREENING FOR APPROPRIATE ASSESSMENT REPORT RESPONSE TO REQUEST FOR FURTHER INFORMATION 23 AUGUST 2019 MGE0741RP0008 Addendum to Edge 2D HR Seismic Survey and Site Survey – Screening for AA Report Response to RFI and Clarifications F01 21 October 2019 rpsgroup.com RESPONSE TO RFI AND CLARIFICATIONS Document status Review Version Purpose of document Authored by Reviewed by Approved by date Response to RFI and Gareth Gareth F01 James Forde 21/10/2019 Clarifications McElhinney McElhinney Approval for issue Gareth McElhinney 21 October 2019 © Copyright RPS Group Limited. All rights reserved. The report has been prepared for the exclusive use of our client and unless otherwise agreed in writing by RPS Group Limited no other party may use, make use of or rely on the contents of this report. The report has been compiled using the resources agreed with the client and in accordance with the scope of work agreed with the client. No liability is accepted by RPS Group Limited for any use of this report, other than the purpose for which it was prepared. RPS Group Limited accepts no responsibility for any documents or information supplied to RPS Group Limited by others and no legal liability arising from the use by others of opinions or data contained in this report. It is expressly stated that no independent verification of any documents or information supplied by others has been made. RPS Group Limited has used reasonable skill, care and diligence in compiling this report and no warranty is provided as to the report’s accuracy. -

![The Irish Mountain Ringlet [Online]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7016/the-irish-mountain-ringlet-online-127016.webp)

The Irish Mountain Ringlet [Online]

24 November 2014 (original version February 2014) © Peter Eeles Citation: Eeles, P. (2014). The Irish Mountain Ringlet [Online]. Available from http://www.dispar.org/reference.php?id=1 [Accessed November 24, 2014]. The Irish Mountain Ringlet Peter Eeles Abstract: The presence of the Mountain Ringlet (Erebia epiphron) in Ireland has been a topic of much interest to Lepidopterists for decades, partly because of the small number of specimens that are reputedly Irish. This article examines available literature to date and includes images of all four surviving specimens that can lay claim to Irish provenance. [This is an update to the article written in February 2014]. The presence of the Mountain Ringlet (Erebia epiphron) in Ireland has been a topic of much interest to Lepidopterists for decades, partly because of the small number of specimens that are reputedly Irish. The Irish Mountain Ringlet is truly the stuff of legend and many articles have been written over the years, including the excellent summary by Chalmers-Hunt (1982). The purpose of this article is to examine all relevant literature and, in particular, the various points of view that have been expressed over the years. This article also includes images of all four surviving specimens that can lay claim to Irish provenance and some of the sites mentioned in conjunction with these specimens are shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 - Key Sites The Birchall Mountain Ringlet (1854) The first reported occurrence of Mountain Ringlet in Ireland was provided by Edwin Birchall (Birchall, 1865) where, -

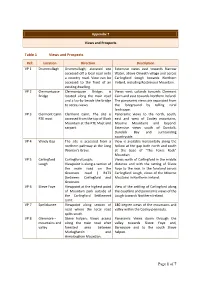

Appendix 11 Views and Prospects

Appendix 7 Views and Prospects Table 1 Views and Prospects Ref: Location Direction Description VP 1 Drummullagh Drummullagh; elevated site Extensive views east towards Narrow accessed off a local road onto Water, above Omeath village and across a country road. View can be Carlingford Lough towards Northern accessed to the front of an Ireland, including Rostrevour Mountain. existing dwelling. VP 2 Clermontpase Clermontpase Bridge; is Views west uplands towards Clermont Bridge located along the main road Cairn and east towards Northern Ireland. and a lay-by beside the bridge The panoramic views are separated from to access views. the foreground by rolling rural landscape. VP 3 Clermont Cairn Clermont Cairn; The site is Panoramic views to the north, south, RTE mast accessed from the top of Black east and west of Cooley mountains, Mountain at the RTE Mast and Mourne Mountains and beyond. carpark. Extensive views south of Dundalk, Dundalk Bay and surrounding countryside. VP 4 Windy Gap The site is accessed from a View is available horizontally along the northern pathway at the Long hollow at the gap both north and south Woman’s Grave. at the base of “The Foxes Rock” Mountian. VP 5 Carlingford Carlingford Lough; Views north of Carlingford in the middle Lough Viewpoint is along a section of distance and with the setting of Slieve the main road on the Foye to the rear. In the foreland across Greenore road ( R173 Carlingford Lough, views of the Mourne )between Carlingford and Moutains in Northern Ireland. Greenore. VP 6 Slieve Foye Viewpoint at the highest point View of the settling of Carlingford along of Mountain park outside of the coastline and panoramic views of the the Carlingford Settlement Lough towards Northern Ireland. -

B6no Slainue an Lartam

Minutes of the meeting of the Western Health Board 5th June 1973 Item Type Meetings and Proceedings Authors Western Health Board (WHB) Publisher Western Health Board (WHB) Download date 27/09/2021 01:35:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10147/89456 Find this and similar works at - http://www.lenus.ie/hse b6no slAinue An lARtAm WESTERN HEALTH BOARD Telephone: Galway 7631 HEADQUARTERS, MERLIN PARK REGIONAL HOSPITAL, GALWAY. 5th June, 1973. To: Each Board Member: Re: Report of Working Party on Psychiatric Nursing Services of Health Boards Dear Member, I enclose, for your information, copy of the above report received today from the Minister for Health. Copies are also being distributed among the Nursing Staffs of these hospitals. Yours sincerely, E. Hannan, Chief Executive Officer. " corresponding upward od)u«t»ont in tho r*vU«d lovel of not expenditure at notified for tho currant financial year. /2 b6RO slAince An lARtAm WESTERN HEALTH BOARD Telephone: Galway 7631 HEADQUARTERS, MERLIN PARK REGIONAL HOSPITAL, GALWAY. 12th June, 1973. To: Each Member of the Board: Re: Future of County Hospital, Roscommon - Acute Hospital Services Dear Member, A Special Meeting of the Board to consider the above matter will be held in the Boardroom here on Monday next, 18th June, at 3.00 p.m. You are hereby requested to attend. Copy of my report enclosed herewith, which, at this stage, should be regarded as strictly confidential, and not for publication before time of meeting. Yours sincerely, &b^^ &vj • E.Jet Hannan , Chief Executive Officer. accordingly anticipated a corresponding upward adjustment in the revised level of net expenditure as notified for the current financial year. -

Information Note:The Maamtrasna Case

Information Note: The Maamtrasna case The tragic event which became known as the Maamtrasna Murders took place on the 17 August 1882. Maamtrasna is a Gaeltacht area located on the shores of Lough Mask on the border between Galway and Mayo. A family of five were slaughtered in their mountainside cottage: John Joyce, his [second] wife Bridget, his daughter, Peigí and his mother Margaret were murdered. His son, Michael, was badly wounded and died the following day as a result of his injuries. The youngest of the family, Patsy, was also injured but survived. The only other member of the family to survive the tragedy was a son Martin who was absent from the home as he was in service in Clonbur at the time. There is no consensus as to the motive for the slaughter and various theories have been suggested. The authorities claimed that John Joyce was treasurer of one of the local secret societies, Ribbonmen/Fenians which opposed the landlords at that time and they suggested the household was attacked because he was alleged to have misappropriated money belonging to the association. However, a more common theory was that John Joyce habitually stole his neighbours’ sheep from the hills and that this was the prime motive for the attack. Others suggested that his mother Margaret was the principal target because she had allegedly informed the authorities about the location in Lough Mask where the bodies of two missing employees of a landlord had been dumped. Still others believed that the murders related to the overly close friendship between the daughter of the house, the teenager Peigí, and a member of the RIC, a relationship which wouldn’t have been acceptable at that time. -

Road Schedule for County Laois

Survey Summary Date: 21/06/2012 Eng. Area Cat. RC Road Starting At Via Ending At Length Central Eng Area L LP L-1005-0 3 Roads in Killinure called Mountain Farm, Rockash, ELECTORAL BORDER 7276 Burkes Cross The Cut, Ross Central Eng Area L LP L-1005-73 ELECTORAL BORDER ROSS BALLYFARREL 6623 Central Eng Area L LP L-1005-139 BALLYFARREL BELLAIR or CLONASLEE 830.1 CAPPANAPINION Central Eng Area L LP L-1030-0 3 Roads at Killinure School Inchanisky, Whitefields, 3 Roads South East of Lacca 1848 Lacka Bridge in Lacca Townsland Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-0 3 Roads at Roundwood Roundwood, Lacka 3 Roads South East of Lacca 2201 Bridge in Lacca Townsland Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-22 3 Roads South East of Lacca CARDTOWN 3 Roads in Cardtown 1838 Bridge in Lacca Townsland townsland Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-40 3 Roads in Cardtown Johnsborough., Killeen, 3 Roads at Cappanarrow 2405 townsland Ballina, Cappanrrow Bridge Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-64 3 Roads at Cappanarrow Derrycarrow, Longford, DELOUR BRIDGE 2885 Bridge Camross Central Eng Area L LP L-1034-0 3 Roads in Cardtown Cardtown, Knocknagad, 4 Roads in Tinnakill called 3650 townsland Garrafin, Tinnakill Tinnakill X Central Eng Area L LP L-1035-0 3 Roads in Lacca at Church Lacka, Rossladown, 4 Roads in Tinnakill 3490 of Ireland Bushorn, Tinnahill Central Eng Area L LP L-1075-0 3 Roads at Paddock School Paddock, Deerpark, 3 Roads in Sconce Lower 2327 called Paddock X Sconce Lower Central Eng Area L LP L-1075-23 3 Roads in Sconce Lower Sconce Lower, Briscula, LEVISONS X 1981 Cavan Heath Survey Summary Date: 21/06/2012 Eng. -

Slieve Bloom Walks Broc 2020 Proof

Tullamore 2020 Slieve Bloom Walking Festival N52 Day Name of Walk Meeting Point Time Grade Distance Duration Leader N80 Sat02-May Capard Woodlands Clonaslee Community Centre 10:30 B 10k 4 hrs Martin Broughan Kilcormac R421 d n Sat Two Rivers/Glendinoregan Clonaslee Community Centre 10:45 A 10k 4 hrs John Scully R422 Clonaslee e N52 Rosenallis Sat Brittas Lake and Woodlands Clonaslee Community Centre 10:30 C 8k 3 hrs Gerry Hanlon Cadamstown Glenbarrow Car Park eek P Sat Spink Mountain Clonaslee Community Centre 11:00 B 8k 4 hrs Richard Jack R440 W Mountmellick Ridge of Cappard Sun03-May Pauls Lane/Silver River Kinnity Community Centre 11:00 C 8k 2 hrs Gerry Hanlon Birr Kinnitty Car Park P N80 Walks 2020 Sun Cumber Hill Kinnity Community Centre 10:30 A 10k 4 hrs John Scully R440 Ballyfin Sun Clear Lake Kinnitty Community Centre 10:45 B 7k 3 hrs Sonja Cadogan R421 Slieve Blm www.fb.com/SlieveBloomOutdoors N62 Camross Portlaoise Sun Kinnitty Woodlands Kinnitty Community Centre 12:30 B 9k 3-4 hrs Richard Jack Muntins N7 Mountrath May Holiday Mon04-May Kinnitty at Dawn Kinnitty Community Centre 06:00 C 6k 2-3 hrs Richard Jack Mon Fearbreague Kinnitty Community Centre 11:00 A 10k 4 hrs Gerry Hanlon Roscrea N7 Borris-in-Ossory BELFAST Eco Walking Weekend 4th-5th July 2020 KNOCK The Slieve Bloom Mountains Day Name of Walk Meeting Point Time Grade Distance Duration Leader DUBLIN - in the Heart of Ireland- SHANNON Sat04-Jul Clonaslee Woodlands Clonaslee Community Centre 11:00 B 12k 4 hrs John Scully ROSSLARE y l WALKERS PLEASE NOTE CORK Ju Sun05-Jul Sillver River Cadamstown Car Park 11:00 B 10k 4 hrs John Scully • Registration takes place prior to start of each walk. -

Che Irish Oracncccc LEARN ORIENTEERING No

New Series of Worksheets for the instruction of beginners: che IRISh oracncccc LEARN ORIENTEERING No. 57 March - April.1992 £1.00 The worksheets are in 6 colors, and feature detailed terrain sketches, color photos and many simple, instructive exercises: Worksheet 1: The most Important map Worksheet 6: Safe features-the thumb grip symbols Worksheet 7: Directional understanding Worksheet 2: Air photos - map symbols Worksheet 8: Contour lines Worksheet 3: Control features Worksheet 9: String Orienteering Worksheet 4: Aligning the map with the Worksheet 10: Route choices terrain Worksheet 11: More route choices Worksheet 5: Handrails Worksheet 12: Draw your own map - Beautifully detailed color terrain - Text and exercises are developed in sketches. cooperation with experienced - Color Terrain Photos for comparing orienteering instructors. map and terrain. - Recommendations for additional - Map examples using easily readable. exercises are Included in the answer - Exercises from many different terrain book and instructor's guide. categories. And, when the new orienteers wanlto learn more about Advanced Orienteering Techniques we recommend the 16 worksheets in the Series Advanced O-Technlque Training. Also, we remind you about the popular orienteering games, Orienteering Bingo and The Orienteering Course for beginners. These games are ideal for beginners instruction and club meetings, and help the players learn map symbols and orienteering basics. Many clubs have used The Orienteering Course as awards. THE ORIENTEERING GAME THE ORIENTEERING COURSE SIMILAR TO BINGO FOR BEGINNERS Consists of 32 different game boards with Game ot chance where the players meet 16 mapsectlons, callers sheet, detailed with the pleasures and the disappoint- directions tor use etc. -

Five Day Itinerary Day

FIVE DAY ITINERARY With lovers’ walks, secluded lakeshores and stunning waterfalls make Killarney the perfect location for a romantic break in Kerry, and ideal location for exploring all our beautiful county has to offer. Here are our favourite places to visit for Couples in Kerry: DAY ONE Killarney National Park, a lover’s paradise secluded hidden lakes, beaches, enchanting waterfalls and mesmerising sunsets. Our favourite spots for the perfect photo together Ross Castle Sits on the edge of Lough Leane, built in the 15th century. Just a stone’s throw from Killarney town, the trip to the castle is best taken by Jaunting Cart. The castle is open for tours throughout the season and boat trips are available to Inisfallen Island from the castle too. Lough Leane The largest of the three lakes of Killarney. Locals and tourists alike pause and catch their breath at its unique natural beauty. Muckross Abbey An old Irish Monastery situated in the middle of the national park. Founded in 1448 as a Franciscan friary, Its most striking feature is a central courtyard, which contains a large yew tree and is surrounded by a vaulted cloister Torc Waterfall A cascade waterfall at 20 metres high, 110 metres long, A short walk of approx 200 metres brings you to the waterfall. From that point steps lead to another viewing point at a higher altitude that provides a view over the Middle Lake. Ladies View Gap of Dunloe, Purple Mountain and the MacGillycuddy Reeks can be seen from Ladies View, an amazing viewing spot – ideal for a romantic snap! Meeting of the Waters Where all three of Killarney’s glorious lakes merge together.