Two: New Maps and Old

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

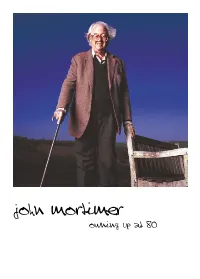

Imagine... John Mortimer

john mortimer owning up at 80 john mortimer owning up at 80 In the year he celebrates his 80th birthday, John Mortimer, the barrister turned author who became a household name with the creation of his popular drama Rumpole of the Bailey, is about to publish his latest book, Where There’s a Will. Imagine captures him pondering on life and offering advice to his children, grandchildren and in his own words “anyone who’ll listen”. John Mortimer’s wit and love of life shines through in this reflection on his life and career.The film eavesdrops on his 80th birthday celebrations, visits his childhood home – where he still lives today – and goes to his old law chambers.There are interviews with the people who know him best, including Richard Eyre, Jeremy Paxman, Kathy Lette, Leslie Phillips and Geoffrey Robertson QC. Imagine looks at the extraordinary influence Mortimer has had on the legal system in the UK.As a civil rights campaigner and defender par excellence in some of the most high-profile, inflammatory trials ever in the UK – such as the Oz trial and the Gay News case – he brought about fundamental changes at the heart of British law. His experience in the courts informs all of Mortimer’s writing, from plays, novels and articles to the infamous Rumpole of the Bailey, whose central character became a compelling mouthpiece for Mortimer’s liberal political views. Imagine looks at the great man of law, political campaigner, wit, gentleman, actor, ladies’ man and champagne socialist who captured the hearts of the British public.. -

And the Publication of James Kirkup's the Love That Dares to Speak Its

2009-2010 ALA MEMORIAL#1 2010 ALA Midwinter Meeting MEMORIAL RESOLUTION HONORING SIR JOHN CLIFFORD MORTIMER WHEREAS, John Mortimer, barrister and author, died on Friday, January 16, 2009, at the age of 85; and WHEREAS, Sir Jolm Clifford Mortimer, CBE, QC (21 April 1923-16 January 2009) on taking silk in 1966 undertook work in criminal law, particularly cases of obscenity charges, successfully defending publishers John Calder and Marion Boyars in their 1968 appeal against their conviction for publishing Hubert Selby, Jr.'s Last Exit to Brooklyn, and three years later, unsuccessfully, for Richard Handyside, the English publisher of The Little Red Schoolbook; and WHEREAS, In 1976 he defended Gay News editor Denis Lemon (Whitehouse v. Lemon) for the publication of James Kirkup's The Love that Dares to Speak its Name against charges of Blasphemous libel and Lemon's conviction was later overturned on appeal; and WHEREAS, His defense of Virgin Records in the 1977 obscenity hearing for their use of the word bollocks in the title of the Sex Pistols' album Never Mind The Bollocks, and the manager of the Nottingham branch of the Virgin record shop chain for the record's display in a window and its sale, led to the defendants being found not guilty; and WHEREAS, Mortimer may be best remembered for his character Horace Rwnpole, the barrister who defends those accused of crime in London's Old Bailey, using that character in Rumpole and the Reign of Terror published in 2006, to challenge the erosion of liberty in the name of national security; now, therefore, be it RESOLVED, That the American Library Association: 1. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced info the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on untii complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

John Clifford Mortimer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2m3n990k No online items Finding Aid to the John Clifford Mortimer Papers Processed by Bancroft Library staff; revised and completed by Kristina Kite and Mary Morganti in October 2001; additions by Alison E. Bridger in February 2004, October 2004, January 2006 and August 2006. Funding for this collection was provided by numerous benefactors, including Constance Crowley Hart, the Marshall Steel, Sr. Foundation, Elsa Springer Meyer, the Heller Charitable and Educational Fund, The Joseph Z. and Hatherly B. Todd Fund, and the Friends of the Bancroft Library. The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the John Clifford BANC MSS 89/62 z 1 Mortimer Papers Finding Aid to the John Clifford Mortimer Papers Collection number: BANC MSS 89/62 z The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: Bancroft Library staff; revised and completed by Kristina Kite and Mary Morganti; additions and revisions by Alison E. Bridger Date Completed: October 2001; additions and revisions February 2004, October 2004, January 2006, August 2006 Encoded by: James Lake © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: John Clifford Mortimer papers, Date (inclusive): circa 1969-2005 Collection Number: BANC MSS 89/62 z Creator: Mortimer, John Clifford, 1923- Extent: Number of containers: 46 boxes Linear feet: 18.4 Repository: The Bancroft Library. -

Paradise Postponed Free

FREE PARADISE POSTPONED PDF Sir John Mortimer | 432 pages | 01 Sep 2011 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141193397 | English | London, United Kingdom Book Reviews, Sites, Romance, Fantasy, Fiction | Kirkus Reviews The series covered a span of 30 years of postwar British history, set in a small village. The series explores the mystery of why Reverend Simeon Simcox, a "wealthy Socialist rector", bequeathed the millions of the Simcox brewery estate to Leslie Titmuss, a city developer and Conservative cabinet minister. The setting of the work in an English Paradise Postponed shows it absorbing and reflecting the Paradise Postponed of British society from the s to the s, and the many changes of the post-World War II society. A three-part sequel, entitled Paradise Postponed Regainedaired in The New York Times described the series as a Paradise Postponed disappointment," with Mortimer having perhaps taken on too much. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Paradise Postponed Novel on which series is based publ. Viking Press. Michael Hordern - Rev. Works by John Mortimer. The Dock Brief Categories : British television series debuts British television series endings s British drama television series s British television miniseries ITV television dramas Television shows based on British novels Period television series Works by John Mortimer Television Paradise Postponed produced by Thames Television Television series by Euston Films English-language television shows Television series about Christian religious leaders. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to Paradise Postponed Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Italiano Edit links. Novel on which series is based publ. -

John Mortimer (Estate) Playwright/Author

John Mortimer (Estate) Playwright/Author John Mortimer was a playwright, novelist and, prior to that, a practising barrister. During the war he worked for the Crown Film Unit and published a number of novels before turning to the theatre. He wrote many film scripts and radio and television plays including six plays on the life of Shakespeare for ATV, SHADES OF GREENE for Thames, UNITY MITFORD for BBC, the adaptation of Evelyn Waugh's novel BRIDESHEAD REVISITED for Granada, a television adaptation of his highly-successful stageplay A VOYAGE ROUND MY FATHER for Thames Television, TTHE EBONY TOWER (an adaptation of John Fowles' Agents Anthony Jones Associate Agent Danielle Walker [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0858 Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Theatre Production Company Notes A VOYAGE ROUND MY FATHER WEST END THE HAIRLESS DIVA THE PALACE THEATRE WATFORD FULL HOUSE THE PALACE THEATRE WATFORD NAKED JUSTICE WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE / BIRMINGHAM HOCK AND SODA WATER CHICHESTER FESTIVAL THEATRE A LITTLE HOTEL ON THE SIDE A VOYAGE ROUND MY FATHER WEST END A VOYAGE ROUND MY FATHER United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes COME AS YOU ARE THE WRONG SIDE OF THE PARK THE DOCK BRIEF SHALL WE TELL CAROLINE Television Production Company Notes LOVE AND WAR IN THE McGee Street Productions/Hall of Calum Blue APPENINES Fame DON QUIXOTE Hallmark/Robert Halmi/Turner Starring John Lithgow -

The Dock Brief.Indd

PACIFIC RESIDENT THEATRE Business Manager Artistic Director Managing Director JENNIFER LONSWAY MARILYN FOX BRUCE WHITNEY The Dock Brief by John Mortimer Executive Producer MARILYN FOX Producers VALERIE HAVEY LIA KOZATCH Associate Producer SARA NEWMAN-MARTINS Scenic Design & Light Design Sound Design NORMAN SCOTT CORWIN EVANS Costume Design Stage Manager AUDREY EISNER MORGAN WILDAY Directed by ROBERT BAILEY CAST Morgenhall . Frank Collison* Fowle . Wesley Mann* A prison cell, Spring 1958 The performance takes place without an intermission. *Members of the Actors Equity Association, the professional union for actors and stage managers in the United States. The Dock Brief is presented by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. The videotaping or making of electronic or other audio and/or visual recordings of this production or distributing recordings on any medium, including the internet, is strictly prohibited, a vio- lation of the author’s rights and actionable under United States copyright law. For more information, please visit www.samuelfrench.com/whitepaper About the Author Sir John Mortimer, CBE (Most Excellent Order of the British Empire), QC (Queen’s Counsel), (21 April 1923 – 16 January 2009), was an English barrister, playwright, and au- thor. Always a bit of a rebel, Mortimer start- ed writing scripts for documentaries after being deemed medically unfi t to for military service in World War II. Although he wanted to be an actor and a writer, Mortimer’s fa- ther, Clifford Mortimer, also a barrister, con- vinced John to enter law school. Mortimer attended Brasenose College, Oxford, and was invited to the bar in 1948. His legal career began with divorce work, but later, Mortimer began defending cases for ending censorship. -

Read Book the Third Rumpole Omnibus

THE THIRD RUMPOLE OMNIBUS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir John Mortimer | 752 pages | 01 Oct 1998 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140257410 | English | London, United Kingdom The Third Rumpole Omnibus PDF Book Edward B. Rumpole and the younger generation by John Mortimer. Professor Andrew Ackerman. Friday there is a lunch break between to , between hese times the library will be shut. Gideon Defoe. Stay in Touch Sign up. Character Parts is a collection of interviews conducted by Mortimer with a diverse group of people including politicians, writers, actresses, bishops, and criminals. Because each style has its own formatting nuances that evolve over time and not all information is available for every reference entry or article, Encyclopedia. He also has a talent for farce as an adapter of Georges Feydeau's plays and as author of his own Come as You Are! Google Books — Loading Six new tales featuring everyone's favorite barris… More. He cannot afford to aim at the [defenseless], nor can he, like the more serious writer, treat any character with contempt. Who rose to enduring fame on Blood and Typewriters… More. Phyllida Erskine-Brown. Please log in Reader code P. Morton International, Inc. His fondness for Wordsworth, Chateau Thames Embankment and hopeless cases Buy this book.. LA Law? Shelve Rumpole and the Angel of Death. Addresses Home—En…. Rumpole of the Bailey is a series of books created and written by the British writer and barrister John Mortimer based on the television series Rumpole of the Bailey. Rumpole and the Barrow Boy [short story] by John Mortimer indirect. Quick Links Amazon. -

Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE E-Mail: [email protected]

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE SHERLOCK HOLMES SOCIETY OF LONDON Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE e-mail: [email protected] no. 236 22 October 2003 To renew your subscription, send 12 stamped, self-addressed the 2002 Audiobook of the Year Award. The Sign of Four is at least envelopes or (overseas) send 12 International Reply Coupons or as good! £6.00 or US$15.00 for 12 issues (dollar checks payable to Jean Thomas B Wheeler’s book Finding Sherlock’s London (see DM Upton, sterling cheques to me). Dollar prices quoted without 230) is now available as an attractive 108-page paperback, 9"x 6", qualification refer to US dollars. You can receive the DM priced at $12.95 or £10.99. Mr Wheeler lists an astonishing 200 electronically free of charge, as a Word 97 attachment or as plain Sherlockian sites, both by adventure and by the nearest text. Please contact me by e-mail (and note the different e-mail Underground station, identified, as he says, ‘with humble detective address). skills, a 1902 London street map, and a large magnifying glass’. The I give such addresses and prices as I have; if I don’t provide details book is essentially a gazetteer, to take along on a tour of Holmes’s of importers or agents, it’s because I don’t have those details. London — a pilgrimage of several days; every location has the John Hawkesworth died on 30 September at the age of 82. His appropriate, accurate information from the Canon. -

The Oxford Book of Villains, 1993, John Mortimer, 0192822772, 9780192822772, Oxford University Press, 1993

The Oxford Book of Villains, 1993, John Mortimer, 0192822772, 9780192822772, Oxford University Press, 1993 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1WYyzgp http://goo.gl/RyHjy http://www.alibris.co.uk/booksearch?browse=0&keyword=The+Oxford+Book+of+Villains&mtype=B&hs.x=19&hs.y=26&hs=Submit "The world may be short of many things," writes John Mortimer in the introduction to this marvelous volume, "rain forests, great politicians, black rhinos, saints, and caviar, but the supply of villains is endless. They are everywhere, down narrow streets and in brightly lit office buildings and parliaments, dominating family life, crowding prisons and law courts, and providing plots for most of the works of fiction that have been composed since the dawn of history." Now, in the ultimate rogue's gallery, Mortimer (best known as the author of Rumpole of the Bailey) has captured an arresting collection of crooks, murderers, seducers, con men, traitors, and tyrants--the world's greatest villains, both fictional and real. Here readers who love mayhem (at least in print) will find villainy in all its shapes and sizes, from pickpockets and pirates to tyrants and financiers. Billy the Kid rubs shoulders with Mac the Knife, Captain Hook with Casanova, Caligula with Rasputin, Fagin with Dr Fu-Manchu. There are master criminals (such as Dr No, Raffles, or Professor Moriarty), minor miscreants (such as P.G. Wodehouse's Ferdie the Fly, "who, while definitely not of the intelligentsia, had the invaluable gift of being able to climb up the side of any house you placed before him, using only toes, fingers and personal magnetism"), and bumbling incompetents (such as Peter Scott, a Briton who in 1980 made seven attempts to kill his wife, without her once noticing that anything was wrong). -

A Rumpole Christmas by John Mortimer, Viking, New York, 161 Pages, $ 21.95

A Rumpole Christmas By John Mortimer, Viking, New York, 161 pages, $ 21.95 Reviewed by Ronald W. Meister he perils of posthumous publishing are prevalent and Christmas pudding. In a way, though, the holiday theme, predictable. For every late author’s Confederacy of such as it is, is a disadvantage, for when stories written over a T Dunces, there is a dreary Silmarillion; for every period of years are collected we see that Mortimer reprised Northanger Abbey, something like Steinbeck’s King Arthur each time the same tired ironies of the curmudgeonly and His Noble Knights. Rare indeed is the secret writer like barrister exchanging with his unappreciative spouse the tie he Emily Dickinson, whose best work was published after death. never wears and the cologne she never uses. Tolkien and Steinbeck presumably knew enough to leave their lesser works in the drawer, and Mark Twain asked that The collection nevertheless provides a varied docket, with an his literary remains be burned, but their publishers thought attempted burglary, two murders, extortion, safe-cracking, otherwise, and their reputations are none the better for it. and Rumpole himself engaging in a little blackmail. Mortimer treats us to several courtroom scenes, at which he The prodigiously prolific John Mortimer, author of fifteen as an experienced trial lawyer excels. But the first four volumes of stories about the loveable Old stories fall a notch below the Bailey hack Horace Rumpole, and three consistently high levels of Mortimer’s dozen other works of fiction, memoir, earlier published works. drama and essay, shuffled off this mortal coil in January, apparently leaving no The redeeming story is the last, briefs unfiled. -

CHAN 9750 FRONT.Qxd 26/7/07 11:10 Am Page 1

CHAN 9750 FRONT.qxd 26/7/07 11:10 am Page 1 CHAN 9750 CHANDOS television NIGEL HESS CHAN 9750 BOOK.qxd 26/7/07 11:14 am Page 2 Jerome Flynn in Badger TV Themes of Nigel Hess 1 Hetty Wainthropp Investigates (BBC) 2:47 © BBC Archive Picture Phillip McCann cornet premiere recording 2 Badger (Feelgood Fiction/BBC) 2:31 Pauline Cato Northumbrian pipes 3 The One Game* (Central TV) 3:08 4 Wycliffe (HTV) 2:52 Anthony Pleeth cello 5 A Woman of Substance (Portman/Channel 4) 2:56 6 Summer’s Lease* (BBC) 3:10 7 Dangerfield (BBC) 3:00 Anthony Pleeth cello 8 Just William (Talisman/BBC) 2:29 premiere recording 9 Every Woman Knows a Secret (Carnival/ITV) 2:50 Mary Carewe vocal 2 3 CHAN 9750 BOOK.qxd 26/7/07 11:14 am Page 4 10 Perfect Scoundrels (TVS) 2:41 20 An Affair in Mind (BBC) 3:18 Chris Laurence bass Olive Simpson vocal 11 Anna of the Five Towns (BBC) 2:54 21 The London Embassy (Thames TV) 2:47 Phillip McCann cornet Maurice Murphy trumpet • Nigel Hess piano 12 Campion (BBC) 2:29 22 Atlantis (BBC) 3:35 John Bradbury violin Phillip McCann cornet • Nigel Hess piano 13 Maigret (Granada TV) 2:53 23 A Hundred Acres (Antelope West/Channel 4) 2:32 Olive Simpson vocal Christopher Lacey flute 14 Vidal in Venice (Antelope/Channel 4) 3:35 24 Growing Pains (BBC) 3:07 Gareth Hulse oboe • Jane Lister harp Nick Curtis vocal 15 Classic Adventure (Mosaic/BBC) 2:42 25 Us Girls (BBC) 2:44 16 All Passion Spent (BBC) 3:31 26 Titmuss Regained (New Penny/Thames TV) 2:46 David Firman piano Christopher Lacey recorder • Peter Willison cello 17 Chimera (Zenith/Anglia TV) 3:27 premiere recording Olive Simpson vocal 27 An Ideal Husband (Wilde Films) 2:59 Rolf Wilson violin 18 Testament (Antelope/Channel 4) 3:22 TT 79:39 Jeremy West cornett * 19 Vanity Fair (BBC) 2:34 Chameleon James Watson trumpet The London Film Orchestra 4 5 CHAN 9750 BOOK.qxd 26/7/07 11:14 am Page 6 Oliver Rokison in Just William Party Questions A: Mainly for television.