The Construction of Sonic Space in Dub Reggae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

The Lions - Jungle Struttin’ for Information and Soundclips of Our Titles, Go to Street Date: 2/19/2008

THE LIONS - JUNGLE STRUTTIN’ FOR INFORMATION AND SOUNDCLIPS OF OUR TITLES, GO TO WWW.UBIQUITYRECORDS.COM/PRESS STREET DATE: 2/19/2008 The LIONS is a unique Jamaican-inspired ------------------------------------------------------------- outfit, the result of an impromptu recording 2 x LP Price 1 x CD Price session by members of Breakestra, Connie ------------------------------------------------------------- Price and the Keystones, Rhythm Roots 01 Thin Man Skank All-Stars, Orgone, Sound Directions, Plant 02 Ethio-Steppers Life, Poetics and Macy Gray (to name a few). Gathering at Orgone's Killion Studios, in Los Angeles during the Fall of 2006, they created 03 Jungle Struttin' grooves that went beyond the Reggae spectrum by combining new and traditional rhythms, and dub mixing mastery with the global sounds of Ethiopia, Colombia and 04 Sweet Soul Music Africa. The Lions also added a healthy dose of American-style soul, jazz, and funk to create an album that’s both a nod to the funky exploits of reggae acts like Byron 05 Hot No Ho Lee and the Dragonaires and Boris Gardner, and a mash of contemporary sound stylings. 06 Cumbia Del Leon The Lions are an example of the ever-growing musical family found in Los Angeles. There is a heavyweight positive-vibe to be found in the expansive, sometimes 07 Lankershim Dub artificial, Hollywood-flavored land of Los Angeles. Many of the members of the Lions met through the LA staple rare groove outfit Breakestra and have played in 08 Tuesday Roots many projects together over the past decade. 09 Fluglin' at Dave's Reggae is a tough genre for a new ensemble act, like the Lions, to dive head-first into and pull off with unquestionable authenticity. -

STAR Digio 100 チャンネル:476 REGGAE 放送日:2009/6/8~6/14 「番組案内(6時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~10:00~16:00~22:00~

STAR digio 100 チャンネル:476 REGGAE 放送日:2009/6/8~6/14 「番組案内(6時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~10:00~16:00~22:00~ 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 REGGAE VIBRATION RASTA SHOULD BE DEEPER JUNIOR KELLY DICK TRACY DEAN FRASER FAMILY AFFAIR SHINEHEAD Zungguzungguguzungguzeng YELLOWMAN CB 200 DILLINGER JAVA AUGUSTUS PABLO REGGAE MAKOSSA Byron Lee & The Dragonaires CUMBOLO CULTURE IT A GO ROUGH Johnny Clarke Got To Be There TOOTS & THE MAYTALS AIN'T THAT LOVING YOU STEELY & CLEVIE featuring BERES HAMMOND (featuring U-ROY) Can I Change My Mind HORACE ANDY Ghetto-Ology SUGAR MINOTT RED RED WINE UB40 BUJU BANTON (1) RASTAFARI BUJU BANTON UNTOLD STORIES BUJU BANTON MAMA AFRICA BUJU BANTON MAYBE WE ARE BUJU BANTON PULL IT UP BERES HAMMOND & BUJU BANTON Hills And Valleys BUJU BANTON 54 / 46 BUJU BANTON featuring TOOTS HIBBERT A LITTLE BIT OF SORRY BUJU BANTON FEELING GROOVY BUJU BANTON Better Must come BUJU BANTON MIRROR BUJU BANTON WHY BUJU LOVE YOU BUJU BANTON We'll Be Alright BUJU BANTON feat. Luciano COVER REGGAE With A Little Help From My Friends Easy Star All-Stars feat. Luciano YOU WON'T SEE ME ERNIE SMITH COME TOGETHER THE ISRAELITES WATCH THIS SOUND THE UNIQUES Holly Holy UB40 BAND OF GOLD SUSAN CADOGAN COUNTRY LIVING (ADAPTED) The mighty diamonds MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGIA TEDDY BROWN TOUCH ME IN THE MORNING JOHN HOLT Something On My Mind HORACE ANDY ENDLESS LOVE JACKIE EDWARDS & HORTNESE ELLIS CAN'T HURRY LOVE~恋はあせらず~ J.C. LODGE SOMEONE LOVES YOU HONEY STEELY & CLEVIE featuring JC LODGE THERE'S NO ME WITHOUT YOU Fiona ALL THAT SHE WANTS PAM HALL & GENERAL DEGREE JUST THE TWO -

LXP NATIVE REVERB BUNDLE OWNER’S MANUAL the LXP Native Reverb Bundle Brings an Inspiring Quality to Your Mixes

LXP NATIVE REVERB BUNDLE OWNER’S MANUAL The LXP Native Reverb Bundle brings an inspiring quality to your mixes. These reverbs are not trying to imitate the real thing, they are the real thing. All four plug-ins are based on uniquely complex algorithms, and each comes with an array of presets to suit your needs. You can tailor each plug-in to your preference or let Lexicon’s trained-ear professionals do the work for you. Place just one instance of the LXP Native Reverbs into your mix, and you will soon appreciate what distinguishes Lexicon from all others. The Lexicon® legacy continues... Congratulations and thank you for purchasing the LXP Native Reverb Plug-in Bundle, an artful blend of four illustrious Lexicon® reverb plug-ins. With a history of great reverbs, the LXP Native Reverb Bundle includes the finest collection of professional factory presets available. Designed to bring the highest level of sonic quality and function to all of your audio applications, the LXP Native Reverb Bundle will change the way you color your mix forever. Quick Start 9 Choose one of the four Lexicon plug-ins. Each plug-in contains a different algorithm: Chamber (LXPChamber) Hall (LXPHall) Plate (LXPPlate) Room (LXPRoom) 9 In the plug-in’s window, select a category 9 Select a preset It can be as simple or as in-depth as you’d like. The 220+ included presets work well for most situations, but you can easily adjust any parameter and save any preset. See page 26 for more information on loading presets, and page 27 for more about saving presets. -

Various the Trojan Skinhead Reggae Collection Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various The Trojan Skinhead Reggae Collection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: The Trojan Skinhead Reggae Collection Country: Europe Released: 2009 Style: Reggae MP3 version RAR size: 1239 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1530 mb WMA version RAR size: 1737 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 227 Other Formats: MIDI APE FLAC MP4 AUD MMF MP1 Tracklist Hide Credits Skinhead Train 1-1 –The Charmers 2:40 Producer – Lloyd CharmersWritten-By – Charmers* Hee Cup 1-2 –Sir Harry 2:14 Producer – Edward 'Bunny' Lee*Written-By – Unknown Artist –King Cannon (Karl Overproof (aka Little Darlin') 1-3 2:41 Bryan)* Producer – Lynford AndersonWritten-By – Williams* Copy Cat 1-4 –Derrick Morgan 2:38 Producer – Leslie KongWritten-By – Morgan* The Law 1-5 –Andy Capp 2:17 Producer – Lynford AndersonWritten-By – Lee*, Anderson* Soul Call 1-6 –The Soul Rhythms 2:57 Producer – J. Sinclair*Written-By – Bryan* Music Street 1-7 –The Harmonians* 1:59 Producer – Edward 'Bunny' Lee*Written-By – Lee* V Rocket 1-8 –The Fabion Producer – Albert Gene Murphy*Written-By – Albert George 2:37 Murphy What Am I To Do 1-9 –Tony Scott 3:15 Producer – Tony Scott Written-By – Scott* Spread Your Bed 1-10 –The Versatiles 2:17 Written-By – Byles* John Public (Tom Hark) 1-11 –The Dynamites 2:13 Producer – Clancy EcclesWritten-By – Bopape* Casa Boo Boo 1-12 –Cool Sticky* Producer – 'Prince' Tony Robinson*Written-By – Unknown 2:33 Artist Smile (My Baby) 1-13 –The Tennors 2:57 Producer – Albert George MurphyWritten-By – Murphy* Zapatoo The Tiger 1-14 –Roland Alphonso 2:38 Producer -

Heather Augustyn 2610 Dogleg Drive * Chesterton, in 46304 * (219) 926-9729 * (219) 331-8090 Cell * [email protected]

Heather Augustyn 2610 Dogleg Drive * Chesterton, IN 46304 * (219) 926-9729 * (219) 331-8090 cell * [email protected] BOOKS Women in Jamaican Music McFarland, Spring 2020 Operation Jump Up: Jamaica’s Campaign for a National Sound, Half Pint Press, 2018 Alpha Boys School: Cradle of Jamaican Music, Half Pint Press, 2017 Songbirds: Pioneering Women in Jamaican Music, Half Pint Press, 2014 Don Drummond: The Genius and Tragedy of the World’s Greatest Trombonist, McFarland, 2013 Ska: The Rhythm of Liberation, Rowman & Littlefield, 2013 Ska: An Oral History, McFarland, 2010 Reggae from Yaad: Traditional and Emerging Themes in Jamaican Popular Music, ed. Donna P. Hope, “Freedom Sound: Music of Jamaica’s Independence,” Ian Randle Publishers, 2015 Kurt Vonnegut: The Last Interview and Other Conversations, Melville House, 2011 PUBLICATIONS “Rhumba Queens: Sirens of Jamaican Music,” Jamaica Journal, vol. 37. No. 3, Winter, 2019 “Getting Ahead of the Beat,” Downbeat, February 2019 “Derrick Morgan celebrates 60th anniversary as the conqueror of ska,” Wax Poetics, July 2017 Exhibition catalogue for “Jamaica Jamaica!” Philharmonie de Paris Music Museum, April 2017 “The Sons of Empire,” Deambulation Picturale Autour Du Lien, J. Molineris, Villa Tamaris centre d’art 2015 “Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s Super Ape,” Wax Poetics, November, 2015 “Don Drummond,” Heart and Soul Paintings, J. Molineris, Villa Tamaris centre d’art, 2012 “Spinning Wheels: The Circular Evolution of Jive, Toasting, and Rap,” Caribbean Quarterly, Spring 2015 “Lonesome No More! Kurt Vonnegut’s -

Jah Stitch, Pioneering Reggae Vocalist, Dies Aged 69

‘Original raggamuffin’ Jah Stitch, pioneering reggae vocalist, dies aged 69 Sound system toaster, DJ and selector, known for his understated delivery and immaculate dress died in Kingston David Katz Thu 2 May 2019 15.03 BSTLast modified on Fri 3 May 2019 09.47 BST FROM: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/may/02/original-raggamu ffin-jah-stitch-pioneering-reggae-vocalist-dies-aged-69 Jah Stitch on Princess Street, downtown Kingston in 2011. Photograph: Mark Read The Jamaican reggae vocalist Jah Stitch died in Kingston on Sunday aged 69, following a brief illness. Although not necessarily a household name abroad, the “original raggamuffin” was a sound system toaster and DJ who scored significant hits in the 70s, later working as an actor and appearing in an ad campaign for Clarks shoes. Born Melbourne James in Kingston in 1949, he grew up with an aunt in a rural village in St Mary, northern Jamaica, since his teenage mother lacked the financial means to care for him. He later joined her in bustling Papine, east Kingston, but conflict with his father-in-law led him to join a community of outcasts living in a tenement yard in the heart of the capital’s downtown – territory aligned with the People’s National party and controlled by the notorious Spanglers gang, which James became affiliated with aged 11. As ska and rock steady gave way to the new reggae style on the nascent Kingston music scene, young James became a regular fixture of sound system dances. He drew his biggest inspiration from the Studio One selections presented by Prince Rough on Sir George the Atomic, based in Jones Town, and the microphone skills of Dennis Alcapone on El Paso, based further west at Waltham Park Road. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

User Manual Delay Tape-201

USER MANUAL Special Thanks DIRECTION Frédéric BRUN Kévin MOLCARD DEVELOPMENT Alexandre ADAM Corentin COMTE Geoffrey GORMOND Mathieu NOCENTI Baptiste AUBRY Simon CONAN Pierre-Lin LANEYRIE Marie PAULI Timothée BEHETY Raynald DANTIGNY Samuel LIMIER Pierre PFISTER DESIGN Shaun ELWOOD Baptiste LE GOFF Morgan PERRIER SOUND DESIGN Jean-Michel BLANCHET TESTING Florian MARIN Germain MARZIN BETA TESTING Paul BEAUDOIN "Koshdukai" Terry MARSDEN George WARE Gustavo BRAVETTI Jeffrey CECIL Fernando M RODRIGUES Chuck ZWICKY Andrew CAPON Ben EGGEHORN Tony Flying SQUIRREL Chuck CAPSIS Mat HERBERT Peter TOMLINSON Marco CORREIA Jay JANSSEN Bernd WALDSTÄDT MANUAL Stephan VANKOV (author) Vincent LE HEN Jose RENDON Jack VAN Minoru KOIKE Charlotte METAIS Holger STEINBRINK © ARTURIA SA – 2019 – All rights reserved. 26 avenue Jean Kuntzmann 38330 Montbonnot-Saint-Martin FRANCE www.arturia.com Information contained in this manual is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of Arturia. The software described in this manual is provided under the terms of a license agreement or non-disclosure agreement. The software license agreement specifies the terms and conditions for its lawful use. No part of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any purpose other than purchaser’s personal use, without the express written permission of ARTURIA S.A. All other products, logos or company names quoted in this manual are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. Product version: 1.0.0 Revision date: 26 August 2019 Thank you for purchasing Delay Tape-201 ! This manual covers the features and operation of the Arturia Delay Tape-201 plug-in. -

The Dub June 2018

1 Spanners & Field Frequency Sound System, Reading Dub Club 12.5.18 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Indigenous Resistance: Ethiopia Dub Journey II Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 25 for the month of Levi. This is our 3rd anniversary issue, Natty Mark founding the magazine in June 2016, launching it at the 1st Mikey Dread Festival near Witney (an event that is also 3 years old this year). This summer sees a major upsurge in events involving members of The Dub family – Natty HiFi, Jah Lambs & Lions, Makepeace Promotions, Zion Roots, Swindon Dub Club, Field Frequency Sound System, High Grade and more – hence the launch of the new Dub Diary Newsletter at sessions. The aim is to spread the word about forthcoming gigs and sessions across the region, pulling different promoters’ efforts together. Give thanks to the photographers who have allowed us to use their pictures of events this month. We welcome some new writers this month too – thanks you for stepping up Benjamin Ital and Eric Denham (whose West Indian Music Appreciation Society newsletter ran from 1966 to 1974 and then from 2014 onwards). Steve Mosco presents a major interview with U Brown from when they recorded an album together a few years ago. There is also an interview with Protoje, a conversation with Jah9 from April’s Reggae Innovations Conference, a feature on the Indigenous Resistance collective, and a feature on Augustus Pablo. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. -

Interview with Donovan Germain 25 Years Penthouse Records

Interview with Donovan Germain 25 Years Penthouse Records 02/19/2014 by Angus Taylor Jamaican super-producer Donovan Germain recently celebrated 25 years of his Penthouse label with the two-disc compilation Penthouse 25 on VP Records. But Germain’s contribution to reggae and dancehall actually spans closer to four decades since his beginnings at a record shop in New York. The word “Germane” means relevant or pertinent – something Donovan has tried to remain through his whole career - and certainly every reply in this discussion with Angus Taylor was on point. He was particularly on the money about the Reggae Grammy, saying what has long needed to be said when perennial complaining about the Grammy has become as comfortable and predictable as the awards themselves. How did you come to migrate to the USA in early 70s? My mother migrated earlier and I came and joined her in the States. I guess in the sixties it was for economic reasons. There weren’t as many jobs in Jamaica as there are today so people migrated to greener pastures. I had no choice. I was a foolish child, my mum wanted me to come so I had to come! What was New York like for reggae then? Very little reggae was being played in New York. Truth be told Ken Williams was a person who was very instrumental in the outbreak of the music in New York. Certain radio stations would play the music in the grave yard hours of the night. You could hear the music at half past one, two o’clock. -

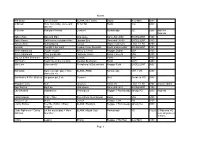

Sheet1 Page 1 809 Band Jam Session BLANK (Hit

Sheet1 809 Band Jam Session BLANK (Hit Factor) Digital Near Mint $200 Al Brown Here I Am baby, come and Tit for Tat Roots VG+ $200 take me Al Senior Bonopart Retreat Coxsone Rocksteady VG $200 Old time Repress Baby Cham Man and Man Xtra Large Dancehall 2000 EXCELLENT $100 Baby Wayne Gal fi come in a dance free Upstairs Ent. Dancehall 95-99 EXCELLENT $100 Banana Man Ruling Sound Taurus Digital clash tune EXCELLENT $250 Benaiah Tonight is the night Cosmic Force Records Roots instrumental EXCELLENT $150 Beres Hammond Double trouble Steely & Clevie Reggae Digital VG+ $150 Beres Hammond They gonna talk Harmony House Roots // Lovers VG+ $150 Big Joe & Bim Sherman Natty cale Scorpio Roots VG+ $400 Big Youth Touch me in the morning Agustus Buchanan Roots VG++ $200 Billy Cole Extra careful Recrational & Educational Reggae Funk EXCELLENT $600 Bob Andy Games people play // Sun BLANK (FRM) Rocksteady VG+ // VG $400 shines for me Bob Marley & The Wailers I'm gonna put it on Coxsone SKA Good+ to VG- $350 Brigadier Jerry Pain Jwyanza Roots DJ EXCELLENT $200 answer riddim Buju Banton Big it up Mad House Dancehall 90's EXCELLENT $100 Carl Dawkins Satisfaction Techniques Reggae // Rocksteady Strong VG $200 Repress Carol Kalphat Peace Time Roots Rock International Roots VG+ $300 Chosen Few Shaft Crystal Reggae Funk VG $250 Clancy Eccles Feel the rhythm // Easy BLANK (Randy's) Reggae // Rocksteady Strong VG $500 snappin Clyde Alphonso // Carey Let the music play // More BLANK (Muzik City) Rocksteady VG $1200 El Flip toca VG Johnson Scorcher pero sin peso