Green Infrastructure SPD - Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMBINED QUALITY and VALUE ASSESSMENT 2015 Avenue

COMBINED QUALITY AND VALUE ASSESSMENT 2015 Park Name Area Ward Hectarage Quality Value High/ Low Childs Hill Park Golders Green & Finchley Childs Hill 3.02 GOOD Good High/High Edgwarebury Park Hendon Edgware 15.95 GOOD Good High/High Golders Hill Park Golders Green & Finchley Childs Hill 14.50 EXCELLENT Good High/High Hendon Park Hendon West Hendon 11.87 GOOD Excellent High/High Heybourne Park Hendon Colindale 6.24 GOOD Good High/High Lyttelton Playing Field Golders Green & Finchley Garden Suburb 9.59 GOOD Fair High/High Malcolm Park Hendon West Hendon 1.90 GOOD Good High/High Mill Hill Park Hendon Mill Hill 18.66 GOOD Good High/High Oak Hill Park Chipping Barnet East Barnet 33.48 GOOD Good High/High Old Court House Recreation Ground Chipping Barnet Underhill 3.08 GOOD Good High/High Victoria Park Golders Green & Finchley West Finchley 7.53 GOOD Good High/High Avenue House Golders Green & Finchley Finchley Church End 4.32 GOOD Poor High/Low Cricklewood Playground Golders Green & Finchley Childs Hill 0.28 GOOD Fair High/Low Hampstead Heath extension Golders Green & Finchley Garden Suburb 30.27 GOOD Fair High/Low Arrandene Open Space Hendon Mill Hill 23.43 FAIR Good Low/High Ashbourne Grove OS Hendon Hale 0.16 FAIR Fair Low/High Barnet Gate Wood Chipping Barnet Underhill 7.89 FAIR Fair Low/High Barnet Hill Open Space Chipping Barnet Underhill 1.63 FAIR Fair Low/High Barnet Playing Field Chipping Barnet Underhill 12.37 FAIR Good Low/High Brent Green Open Space Hendon Hendon 0.29 FAIR Fair Low/High Brent Park Hendon Hendon 3.44 FAIR Good Low/High -

28 Westbury Brochure.Qxp Layout 1

Sales Agent: LONDON N12 www.westburyN12.com First-time buyers from across the UK can buy at The Westbury with just a 5% deposit. www.helptobuy.gov.uk Cover photo: Dollis Brook flows gently along the edge of the garden as it passes unnoticed through 10 miles of busy London life. LONDON N12 A collection of thirty four exquisitely finished apartments with secure underground parking, excellent transport links, great local amenities and green spaces. The Westbury offers the very best of urban and rural living. | 4 Countryside at your backdoor As the name suggests, Woodside Park sits adjacent to a vast green space consisting of woods, grassland and open pastures. Amazingly this urban oasis has avoided development and is now a protected green belt site occupying the valley between Mill Hill and Totteridge. 2 The Westbury sits right on the edge of this open space at the confluence of Folly and Dollis brooks. These streams are flanked by the Dollis Valley Green Walk, a stretch of lush green space that meanders quietly through a series of North London neighbourhoods as it makes its way from Totteridge Village down to the Brent Reservoir. 3 Other local parks include the well kept Victoria Park off Ballards Lane, which offers tranquil spaces on neatly trimmed lawns to relax, unwind and stretch the legs. If you are looking to keep active, the flat and well-surfaced paths are ideal for a morning jog. You will also find tennis courts, a bowling green and sports clubs to join. If golf is your thing, you’ll will be spoilt for choice, with 12 golf courses within a 5 mile radius of The Westbury. -

Brent Valley & Barnet Plateau Area Framework All London Green Grid

All Brent Valley & Barnet Plateau London Area Framework Green Grid 11 DRAFT Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 9 Area Description 10 Strategic Context 11 Vision 14 Objectives 16 Opportunities 20 Project Identification 22 Clusters 24 Projects Map 28 Rolling Projects List 34 Phase One Early Delivery 36 Project Details 48 Forward Strategy 50 Gap Analysis 51 Recommendations 52 Appendices 54 Baseline Description 56 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA11 Links 58 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA11 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www.london.gov.uk/publication/all-london- green-grid-spg . Cover Image: View across Silver Jubilee Park to the Brent Reservoir Foreword 1 Introduction – All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology Introduction Area Frameworks Partnership - Working The various and unique landscapes of London are Area Frameworks help to support the delivery of Strong and open working relationships with many recognised as an asset that can reinforce character, the All London Green Grid objectives. -

Appendix 1 Draft Greenspace Capital Investment Strategy , Item 14

Environment Committee: 08 November 2016 Implementation of the Parks and Open Spaces Strategy Appendix 1: Draft Greenspaces Capital Investment Programme The proposed Greenspaces Capital Investment Programme amounts to £105m over a 5-10 year period (transformational schemes will have longer timescales due to funding, e.g. Brent Cross and Heritage Parks projects), detailed throughout this document. This is proposed to be delivered through a split of 56% developer funding, 22% grant funding and 22% LBB Capital Funding (mainly borrowing), and meaning that 78% of the total cost of the programme is to be funded through external sources of funding. The table shows the proposed approach to investment in open spaces to maximise the strategic benefit and funding opportunity from Council investment through both the development reserve and other capital funding (mostly borrowing, but some specific capital receipts). In most cases borrowing proposals have been linked to assets such as pavilions or roads/footpaths, but in a few places the shift towards ‘Natural Capital Accounting’ adopted through the Open Spaces Strategy may need to be utilised to support proposed borrowing. Site Description/Comments Total cost S106 Dev. Grants LBB Reserve Capital Existing Capital Colindale Parks (Transformational 12,000,000 150,000 8,350,000 3,500,000 0 Programme Investment) Targeted Small Scale Investments 622,000 189,000 0 18,000 415,000 SUB -TOTAL 12,622,000 339,000 8,350,000 3,518,000 415,000 Proposed 15,115,00 Regeneration and Growth Areas 36,800,000 6,900,000 9,110,000 5,675,000 ‘Transformationa 0 l’ Capital Development Areas 8,500,000 7,800,000 600,000 100,000 0 Investments Sports Hubs 14,450,000 3,950,000 4,950,000 2,300,000 3,250,000 Heritage Parks 10,973,000 0 2,070,000 5,175,000 3,728,000 26,865,00 14,520,00 16,685,00 12,653,00 SUB-TOTAL 70,723,000 0 0 0 0 Site Description/Comments Total cost S106 Dev. -

Green Infrastructure and Open Environments

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE AND OPEN ENVIRONMENTS: London’s FOUNDATIONS: PROTECTING THE GEODIVERSITY OF THE CAPITAL SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING GUIDANCE MARCH 2012 LONDON PLAN, 2011 IMPLEMENTATION FRAMEWORK ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The work to prepare and produce London’s Foundations, published in 2009 was made possible by funding from Natural England via the Defra Aggregates Levy Sustainability fund (ALSF), The Greater London Authority (GLA), British Geological Survey (BGS) and Natural England London Region. In-kind project support was provided by London Borough of Lambeth, Natural England, Hanson UK, British Geological Survey, Harrow and Hillingdon Geological Society, South London RIGS Group and London Biodiversity Partnership. BGS prepared the draft report in 2008 on behalf of the London Geodiversity Partnership, led by the GLA. BGS is a component body of the Natural Environment Research Council. BGS Report authors: H F Barron, J Brayson, D T Aldiss, M A Woods and A M Harrison BGS Editor: D J D Lawrence The 2012 update was prepared by Jane Carlsen and Peter Heath of the Greater London Authority with the assistance of the London Geodiversity Partnership. Mapping updates provided by Julie MacDonald of Greenspace Information for Greater London. Document production by Alex Green (GLA). The Mayor would like to acknowledge the work and extend thanks to the London Geodiversity Partnership who contributed to the revision of London’s Foundations SPG and those who responded to the consultation. Maps and diagrams have been prepared by the authors, except where stated. This report includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance Survey with permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright and/or database right 2008. -

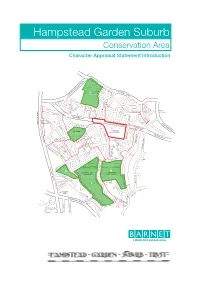

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation Area Character Appraisal Statement Introduction For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb 5 1.2 Conservation areas 5 1.3 Purpose of a character appraisal statement 5 1.4 The Barnet unitary development plan 6 1.5 Article 4 directions 7 1.6 Area of special advertisement control 7 1.7 The role of Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust 8 1.8 Distinctive features of this character appraisal 8 Section 2 Location and uses 10 2.1 Location 10 2.2 Uses and activities 11 Section 3 The historical development of Hampstead Garden Suburb 15 3.1 Early history 15 3.2 Origins of the Garden Suburb 16 3.3 Development after 1918 20 3.4 1945 to the present day 21 Section 4 Spatial analysis 22 4.1 Topography 22 4.2 Views and vistas 22 4.3 Streets and open spaces 24 4.4 Trees and hedges 26 4.5 Public realm 29 Section 5 Town planning and architecture 31 Section 6 Character areas 36 Hampstead Garden Suburb Character Appraisal Introduction 5 Section 1 Introduction 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb Hampstead Garden Suburb is internationally recognised as one of the finest examples of early twentieth century domestic architecture and town planning. -

Q.1 How Often Do You Visit a Park Or Open Space in Barnet?

A1744 BarnetBarnet OSSOSS CitizensCitizens Pannel Panel SummarySummary Report Q.1 How often do you visit a park or open space in Barnet? Every day Never visit 0% 5% Most days Once a year 21% 2% Two or three times a year 14% Once a month 17% Once or twice a week 28% Once every two weeks 13% No % of total Never visit 37 5.2 Once a year 15 2.1 Two or three times a year 98 13.9 Once a month 122 17.3 Once every two weeks 91 12.9 Once or twice a week 198 28.1 Most days 144 20.4 Every day 0 0.0 A1744A1744 Barnet Barnet OSS OSS Citizens Citizens Panel Pannel Summary Summary Report Report Q.2 Could you please tell us why you don’t visit parks and open spaces in the borough, could you please tell us why. 35 29.7% 30 27.0% 27.0% 27.0% 25 20 15 10.8% 10.8% 10 8.1% 8.1% 5.4% 5.4% 5 0 I do not have I am not I do not feel Barnet’s parks Barnet’s parks Barnet’s parks My health is too There is no I prefer to visit Other time interested in safe visiting and open and open and open poor suitable public parks and open them them spaces do not spaces are not spaces are not transport to get spaces outside offer facilities I easy to get to well maintained to them the borough want No % of total I do not have time 11 29.7 I am not interested in them 3 8.1 I do not feel safe visiting them 10 27.0 Barnetʼs parks and open spaces do not offer faci 4 10.8 Barnetʼs parks and open spaces are not easy to 3 8.1 Barnetʼs parks and open spaces are not well ma 2 5.4 My health is too poor 10 27.0 There is no suitable public transport to get to the 2 5.4 I prefer to visit parks and open spaces outside th 4 10.8 Other 10 27.0 Total responses (as per Q1) 37 Other: I feel uncomfortable visiting parks and open spaces alone not that I don't have a dog. -

Barnet Plateau

3. Barnet Plateau Key plan Description The Barnet Plateau Natural Landscape Area is part of a plateau of higher land on the north-west rim of the London Basin. The area extends eastwards to the Dollis Brook through East Barnet, southwards as far as the Brent Reservoir, and westwards to the River Crane. It covers a large and very varied area. The underlying geology is dominated by London Clay, but in the northern (and higher) part of the Natural Landscape Area, the summits are defined by more coarse grained, younger rocks of the Claygate Member, and further south a couple of outlying hills are capped by 3. Barnet Plateau Barnet 3. the sandier rocks of the Bagshot Formation. The latter typically has steep convex slopes and is very free-draining; it tends to support ENGLAND 100046223 2009 RESERVED ALL RIGHTS NATURAL CROWN COPYRIGHT. © OS BASE MAP heathland vegetation. Superficial deposits of Stanmore Gravels overlie 3. Barnet Plateau the northern areas of this Landscape Area. These correspond with the underlying Claygate Member on the higher points of the plateau (e.g. High Barnet 134m OD). The plateau slopes within the northern part of the Landscape Area may have been shaped by periglacial erosion following the Anglian glacier advance in the Finchley area to the east. The early settlement cores (Stanmore, Harrow, Hadley and Horsenden) are linked by the extensive urban areas of Barnet, Edgware, Kenton, To the north there are patches of farmland with rectangular fields Further south, the built up areas are frequently punctuated by patches Wembley and Greenford. Parts of Harrow have late-Victorian/ enclosed by hedgerows. -

Eastbrookend Country Park (Beam Valley Extension), Mayesbrook Park Lake

THE EXECUTIVE 8 FEBRUARY 2005 REPORT FROM THE DIRECTOR OF REGENERATION AND ENVIRONMENT EASTBROOKEND COUNTRY PARK (BEAM VALLEY FOR DECISION EXTENSION), MAYESBROOK PARK LAKE (SOUTH) AND PARSLOES PARK (SQUATTS) - DECLARATION OF LOCAL NATURE RESERVES This report concerns a strategic matter and is therefore reserved to the Executive by the Scheme of Delegation. Summary The designation of Eastbrookend Country Park (Beam Valley extension), Mayesbrook Park Lake (South) and Parsloes Park ‘Squatts’ are the second targets to be achieved under the Borough’s Local Public Service Agreement with the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Following consultation with English Nature, it is proposed to designate these sites as the Borough’s latest Local Nature Reserves. This follows the designation of The Chase as a Local Nature Reserve (2001) and Eastbrookend Country Park (2003) Plans showing the proposed areas to be designated are attached (Appendices A-C) Recommendation The Executive is recommended to: (i) approve the declaration of Eastbrookend Country Park (Beam Valley extension), Mayesbrook Park Lake (South) and Parsloes Park ‘Squatts’, as marked on the attached plans, as Local Nature Reserves (LNR’s); and (ii) authorise Officers to issue the necessary Notices and enter into the necessary legal arrangements to enable the Declarations to take place. Reason The designation of these sites as Local Nature Reserves will assist the Council in achieving its Community Priorities of ‘Making Barking and Dagenham Cleaner, Greener and Safer’ and ‘Raising General Pride in the Borough’. Wards Affected Village Ward; - Eastbrookend Country Park (Beam Valley extension); Mayesbrook Ward; - Mayesbrook Park Lake (South) and Parsloes Park ‘Squatts’ Contact: Mike Levett Senior Park Development Officer Tel: 020 - 8227 3387 Fax: 020 - 8227 3129 Minicom: 020 - 8227 3042 E-mail: [email protected] 1. -

Investing in Our Communities

Investing in our communities Community Investment Programme Summary 2014-2020 Walthamstow Wetlands Our commitment to Public Value is all about contributing to society while delivering life’s essential service. Protecting the environment, enriching lives and helping those who need it most is at the heart of this commitment, and we’re proud to be part of the communities we serve. We work in five-year funding cycles (AMP periods), which we agree with our regulator Ofwat. At the end of our last funding Did you know? cycle, we committed to investing £8.5 million in community-based Our community investment initiatives within our region over five years. This was funded by our shareholders in agreement with Ofwat and formed the basis of our AMP6 community investment programme has reached over programme. one million people This report details some the fantastic partners we’ve worked with to make our community investment projects a success. £2 million for our Trust Fund £6.5 million for community investment and education Summary Programme Investment Community 2015-2020 We provided £2 million for our Thames Water Trust Fund - a We allocated £6.5 million to fund 60 community projects as well as our popular education centres. registered charity that provides critical assistance for our most vulnerable customers. Focusing on engagement, learning and environmental enhancement, we contributed to schemes in the following areas: Our Trust Fund is split into two areas: the Organisational Grant Programme, which provides debt and money advice services to the local community, and the Hardship Fund, which helps people who are in need of more immediate support by Education and Biodiversity and Sustainable urban Improving green Encouraging Heritage Health through Citizen Science 2015-2020 providing grants towards essential household items. -

River Thames and Tidal Tributaries Summary

Metropolitan Site Reference: M031 Site Name: River Thames and tidal tributaries Summary: The Thames, London’s most famous natural feature, is home to many fish and birds, creating a wildlife corridor running right across the capital. Grid ref: TQ 302 806 Area (ha): 2304.92 ha in London, 171.22 ha in Barking and Dagenham Borough(s): Barking and Dagenham, Bexley, City of London, Greenwich, Hammersmith and Fulham, Havering, Hounslow, Kensington and Chelsea, Kingston upon Thames, Lambeth, Lewisham, Newham, Richmond upon Thames, Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Wandsworth, Westminster Habitat(s): Intertidal, Marsh/swamp, Pond/Lake, Reed bed, Running water, Saltmarsh, Secondary woodland, Vegetated wall/tombstones, Wet ditches, Wet grassland, Wet woodland/carr Access: Free public access (part of site) Ownership: Port of London Authority (Tidal banks) and Private (Riparian owners (non tidal banks)) Site Description: The River Thames and the tidal sections of creeks and rivers which flow into it comprise a number of valuable habitats not found elsewhere in London. The mud-flats, shingle beach, inter-tidal vegetation, islands and river channel itself support many species from freshwater, estuarine and marine communities which are rare in London. The site is of particular importance for wildfowl and wading birds. The river walls, particularly in south and east London, also provide important feeding areas for the nationally rare and specially-protected black redstart. The Thames is extremely important for fish, with over 100 species now present. Many of the tidal creeks are important fish nurseries, including for several nationally uncommon species such as smelt. Barking Creek supports extensive reed beds. Further downstream are small areas of saltmarsh, a very rare habitat in London, where there is a small population of the nationally scarce marsh sow-thistle (Sonchus palustris). -

Should the Suburb Stop the Fireworks?

www.hgs.org.uk Issue 141 · Winter 2020 Young Suburbite RA Chair, Jean Neal is stays up to enjoy Emma Howard’s honoured to the NYE party email bag, p8 reveal all, p5 Should the Suburb MICHAEL ELEFTHERIADES stop the Fireworks? Like many inventions, fireworks there was a firework display stewards on hand, ensuring it were created by accident... and by because of a ‘letter’ written by was both dazzling and safe. the search for immortality. Around merchant Robert Laneham. His Yet, for all their beauty, we 800 AD, a Chinese alchemist eyewitness account, frustratingly, ought to be mindful that there mixed sulphur, charcoal, and doesn’t go into any detail about can be serious problems with potassium nitrate hoping to find the fireworks, but, he does write fireworks. An obvious one is the the secret to eternal life. Instead, that the “blaze of burning darts, noise which can terrify animals the mixture caught fire and gun- flying to & fro, streams and hail and young children. Fireworks powder was born. Legend has it of fiery sparks, lightnings of are also known to be a main that a little later, a Chinese monk, wildfire on water and land, flight contributor of accidents during stuffed bamboo with the saltpeter- & shoots of thunderbolts: all with parties and celebrations. Then, based gunpowder and launched such …terror and vehemence, of course, there is also the it into a fire causing a modest that the heavens thundered, the environmental impact. explosion and an impressive bang, waters scourged, the earth shook.” This year, China’s largest city, along with a bright spray of He was certainly impressed.