THE EIGHT GATES of ZEN a Program of Zen Training

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

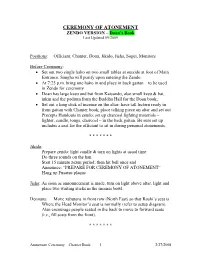

CEREMONY of ATONEMENT ZENDO VERSION – Doan’S Book Last Updated 09/2009

CEREMONY OF ATONEMENT ZENDO VERSION – Doan’s Book Last Updated 09/2009 Positions: Officiant, Chanter, Doan, Jikido, Jisha, Sogei, Monitors Before Ceremony: Set out two single hako on two small tables at outside at foot of Main Entrance. Sangha will purify upon entering the Zendo. At 7:25 p.m. bring one hako in and place in back gaitan – to be used in Zendo for ceremony Doan has large kesu and bai from Kaisando, also small kesu & bai, inkin and the podium from the Buddha Hall for the Doan book; Set out a long stick of incense on the altar; have tall lectern ready in front gaitan with Chanter book; place talking piece on altar and set out Precepts Handouts in zendo; set up charcoal lighting materials – lighter, candle, tongs, charcoal – in the back gaitan. Be sure set up includes a seat for the officiant to sit in during personal atonements. * * * * * * * Jikido: Prepare zendo: light candle & turn on lights at usual time Do three rounds on the han Start 15 minute zazen period; then hit bell once and Announce: “PREPARE FOR CEREMONY OF ATONEMENT” Hang up Fusatsu plaque Jisha: As soon as announcement is made, turn on light above altar, light and place two waiting sticks in the incense bowl. Dennans: Move zabutans in front row (North East) so that Roshi’s seat is Where the Head Monitor’s seat is normally (refer to setup diagram). Also encourage people seated in the back to move to forward seats (i.e., fill seats from the front). * * * * * * * Atonement Ceremony – Chanter Book 1 2/27/2008 Officiant Entry: (usual entry) Officiant enters (Doan chings at entry, halfway to haishiki, and at bow at haishiki) and goes up to altar to offer stick incense. -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

The Zen Koan; Its History and Use in Rinzai

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE TRENT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/zenkoanitshistorOOOOmiur THE ZEN KOAN THE ZEN KOAN ITS HISTORY AND USE IN RINZAI ZEN ISSHU MIURA RUTH FULLER SASAKI With Reproductions of Ten Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku A HELEN AND KURT WOLFF BOOK HARCOURT, BRACE & WORLD, INC., NEW YORK V ArS) ' Copyright © 1965 by Ruth Fuller Sasaki All rights reserved First edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-19104 Printed in Japan CONTENTS f Foreword . PART ONE The History of the Koan in Rinzai (Un-chi) Zen by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Koan in Chinese Zen. 3 II. The Koan in Japanese Zen. 17 PART TWO Koan Study in Rinzai Zen by Isshu Miura Roshi, translated from the Japanese by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Four Vows. 35 II. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (i) . 37 vii 8S988 III. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (2) . 41 IV. The Hosshin and Kikan Koans. 46 V. The Gonsen Koans . 52 VI. The Nanto Koans. 57 VII. The Goi Koans. 62 VIII. The Commandments. 73 PART THREE Selections from A Zen Phrase Anthology translated by Ruth F. Sasaki. 79 Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku.123 Index.147 viii FOREWORD The First Zen Institute of America, founded in New York City in 1930 by the late Sasaki Sokei-an Roshi for the purpose of instructing American students of Zen in the traditional manner, celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary on February 15, 1955. To commemorate that event it invited Miura Isshu Roshi of the Koon-ji, a monastery belonging to the Nanzen-ji branch of Rinzai Zen and situated not far from Tokyo, to come to New York and give a series of talks at the Institute on the subject of koan study, the study which is basic for monks and laymen in traditional, transmitted Rinzai Zen. -

Publications Received by the Regional Editor for South-Asia (From April 2001 to November 2002)

Publications received by the regional editor for South-Asia (from April 2001 to November 2002) Objekttyp: Group Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 57 (2003) Heft 1 PDF erstellt am: 10.10.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch PUBLICATIONS RECEIVED by the regional editor for South-Asia (from April 2001 to November 2002) Adachi, Toshihide (2001): '"Hearing Amitäbha's name' in the Sukhâvatî-vyûha." Buddhist and Pure Land Studies. Felicitation volume for Takao Kagawa on his Seventieth Birthday. Kyoto: Nagata-bunshö -do. Pp. 21-38. -

Moral and Ethical Teachings of Zen Buddhism

The Heart of Being: Moral and Ethical Teachings of Zen Buddhism The Heart of Being: Moral and Ethical Teachings of Zen Buddhism #0804830789, 9780804830782 #267 pages #Tuttle Publishing, 1996 #1996 #John Daido Loori, Bonnie Myotai Treace, Konrad Ryushin Marchaj "The Buddhist Precepts are the vows taken as an initiation into Buddhism and reflect the Buddha's teachings on a wide range of social and moral issues. In The Heart of Being acclaimed Zen master John Daido Loori provides a modern interpretation of these precepts and explains the traditional precept ceremony, known as jukai. He also offers commentary on Master Dogen's own instructions about the precepts and discusses the ethical significance of these vows both within the context of formal Zen training and as guidelines for living an enlightened life." "This is an important text not only for those studying Buddhism but for all of us struggling to navigate the dilemmas of our modern lives. As Daido Loori demonstrates, the Buddha's teachings can serve as a true moral compass to wise, compassionate, and "right" action."--BOOK JACKET.Title Summary field provided by Blackwell North America, Inc. All Rights Reserved DOWNLOAD http://relevantin.org/2fk54Qn.pdf Invoking Reality #Moral and Ethical Teachings of Zen #There is a common misconception that to practice Zen is to practice meditation and nothing else. In truth, traditionally, the practice of meditation goes hand-in-hand with #Religion #ISBN:9781590304594 #97 pages #2007 #John Daido Loori DOWNLOAD http://relevantin.org/2fk7H4I.pdf And skills become rote, empty, tiresome, and finally lifeless without this heart, by whatever about the competing reli- gious views and affiliations of politicians; moral and social participation in supportive aspects of religious communities are associated with enhanced well-being. -

Zen Heart Sangha Jikido Schema Sesshin

Zen Heart Sangha Jikido schema Sesshin Als Jikido heb je tot taak om de zendo te beheren, de meditatie volgens het schema gaande te houden en vooral om de aanwezigen in staat te stellen zich helemaal aan hun beoefening te wijden zonder zich met andere dingen bezig te hoeven houden. Je stelt je beoefening dus voor een groot deel ten dienste van de anderen. Je beoefening als Jikido is, om je zo veel mogelijk bewust te zijn van de deelnemers en van de gang van zaken in de zendo. Je richt je op het welzijn van de deelnemers en op wat er gaande is in de zendo en neemt daar ook mede de verantwoordelijkheid voor. Je bent niet alleen verantwoordelijk voor de zendo, je bent ook de gastheer/vrouw in de zendo en je belichaamt het praktisch functioneren van Zazen. Je bent de persoonlijke expressie van het niet-persoonlijke, altijd klaar om te handelen naar gelang de situatie vergt. Je doet gewoon wat gedaan moet worden vanuit een milde, open, responsieve staat van zijn. Als Jikido zorg je ervoor dat je op tijd in de zendo bent. Je regelt de verlichting, de temperatuur en de ventilatie, en checkt eventueel of het altaar op orde is (bloemen, kaars, wierookbrander, wierookstaafjes). Je volgt nauwkeurig het tijdschema zonder inflexibel te zijn. Je zoekt op eigen initiatief de leraar of de Jisha op om het schema up to date te houden en je wordt door de leraar ook zo goed mogelijk op de hoogte gehouden van eventuele veranderingen. Eerste zitperiode 0700 zazen (40m zen - 10m kinhin - 30m zen - 10m kinhin - 30m zen) 0630 Wekken. -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his. -

Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism

Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism STEVEN HEINE DALE S. WRIGHT, Editors OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Zen Classics This page intentionally left blank Zen Classics Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism edited by steven heine and dale s. wright 1 2006 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright ᭧ 2006 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zen classics: formative texts in the history of Zen Buddhism / edited by Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: The concept of classic literature in Zen Buddhism / Dale S. Wright—Guishan jingce and the ethical foundations of Chan practice / Mario Poceski—A Korean contribution to the Zen canon the Oga hae scorui / Charles Muller—Zen Buddhism as the ideology of the Japanese state / Albert Welter—An analysis of Dogen’s Eihei goroku / Steven Heine—“Rules of purity” in Japanese Zen / T. -

Guide to Form 5Th Draft

Form Guide StoneWater Zen Sangha Form Guide Keizan Sensei on form Page 3 Introduction to the Guide 4 Part One: Essentials 5 Entering the zendo 6 Sitting in the zendo 7 Kin-Hin 8 Interviews 9 Teacher's entrance and exit 10 An Introduction to Service 12 Part Two: Setting up and Key Roles 14 The Altar, Layout of the zendo 15 Key Roles in the zendo 16 Jikido 16 Jisha 18 Chiden, Usher, Monitor 19 Service Roles 20 Ino 20 Doan 22 Mokugyo 23 Dennan, Jiko 24 Sogei 25 Glossary 26 Sources 28 September 2012 Page 2 StoneWater Zen Sangha Form Guide Keizan Sensei on form This Form Guide is intended as a template that can be used by all StoneWater Zen sangha members and groups associated with StoneWater such that we can, all together, maintain a uniformity and continuity of practice. The form that we use in the zendo and for Zen ceremonies is an important part of our practice. Ceremony, from the Latin meaning 'to cure,' acts as a reminder of how much there is outside of our own personal concerns and allows us to reconnect with the profundity of life and to show our appreciation of it. Form is a vehicle you can use for your own realisation rather than something you want to make fit your own views. To help with this it is useful to remember that the structure though fixed is ultimately empty. Within meditation and ceremony form facilitates our moving physically and emotionally from our usual outward looking personal concerns to the inner work of realisation and change. -

Winter 2014•2015 Daido Roshi the Zen Practitioner's Journal

The Journal Zen Practitioner’s 2015 • Daido Roshi Winter 2014 Winter $9.00 / $10.00 Canadian $10.00 / $9.00 MOUNTAIN RECORD Daido Roshi Vol. 33.2 Winter 2014 ● 2015 DHARMA COMMUNICATIONS Box 156MR, 831 Plank Road P.O. NY 12457 Mt. Tremper, (845) 688-7993 Gift Package Includes a one-year print subscription to the award-winning quarterly journal Mountain Record, a Green Verawood Wrist Mala, and our signature black Wake Up Coffee Mug at a savings. Was $49 now! $44. New and Gift Subscriptions New subscribers receive 20% off the regular subscription price for the print edition. Was $32 now $26. Or, order the digital edition for $25 and get a free issue. In either case, you John Daido Loori or your gift recipient will receive their first issue right away! Mountain Record Dharma Communications President Geoffrey Shugen Arnold Sensei, MRO DC Director of Operations Mn. Vanessa Zuisei Goddard, MRO DC Creative Director & Editor Danica Shoan Ankele, MRO MOUNTAIN RECORD (ISSN #0896-8942) is published quarterly by Dharma Communications. Periodicals Postage Paid at Mt. Tremper, NY, and additional mailing offices. Layout and Advertising Nyssa Taylor, MRO Postmaster: send address changes to MOUNTAIN RECORD, P.O. Box 156, Mt. Tremper, NY 12457-0156. Yearly subscription of four issues: $32.00. To subscribe, call us at (845) 688-7993 or send a check payable to Dharma Communications at the address below. Postage outside ter ri to ri al U.S.: add $20.00 per year (pay in U.S. cur ren cy). Back issues are avail able for $9.00. -

The Interconnectedness of Well-Being Zen Buddhist Teachings on Holistic Sustainability

The Interconnectedness of Well-Being Zen Buddhist Teachings on Holistic Sustainability Tess Edmonds AHS Capstone Project, Spring 2011 Disciplinary Deliverable P a g e | 2 I swear the earth shall surely be complete to him or her who shall be complete, The earth remains jagged and broken only to him or her who remains jagged and broken I swear, there is no greatness of power that does not emulate those of the earth, There can be no theory of any account unless it corroborate the theory of the earth, No politics, song, religion, behavior, or what not, is of account unless it compare with the amplitude of the earth, Unless it face the exactness, vitality, impartiality, rectitude of the earth. I swear I begin to see love with sweeter spasms than that which responds love, It is that which contains itself, which never invites and never refuses. I swear, I begin to see little or nothing in audible words, All merges toward the presentation of the unspoken meanings of the earth, Toward him who sings the songs of the body and of the truths of the earth, Toward him who makes the dictionaries of words that print cannot touch. -Walt Whitman P a g e | 3 A PERSONAL NOTE OF INTRODUCTION This project began with a personal journey of exploration, experience, and thinking about how to bring together areas I have increasingly sensed are interrelated. As far back as I can remember, I have always had a deep-rooted love for Nature – a quiet reverence for the mountains and rivers, animals and plants with which we share this planet.