Professional Profiles, Pedagogic Practices, and the Future of Guitar Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

BEACH BOYS Vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music

The final word on the Beach Boys versus Beatles debate, neglect of American acts under the British Invasion, and more controversial critique on your favorite Sixties acts, with a Foreword by Fred Vail, legendary Beach Boys advance man and co-manager. BEACH BOYS vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music Buy The Complete Version of This Book at Booklocker.com: http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/3210.html?s=pdf BEACH BOYS vs Beatlemania: Rediscovering Sixties Music by G A De Forest Copyright © 2007 G A De Forest ISBN-13 978-1-60145-317-4 ISBN-10 1-60145-317-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Printed in the United States of America. Booklocker.com, Inc. 2007 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY FRED VAIL ............................................... XI PREFACE..............................................................................XVII AUTHOR'S NOTE ................................................................ XIX 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD 1 2. CATCHING A WAVE 14 3. TWIST’N’SURF! FOLK’N’SOUL! 98 4: “WE LOVE YOU BEATLES, OH YES WE DO!” 134 5. ENGLAND SWINGS 215 6. SURFIN' US/K 260 7: PET SOUNDS rebounds from RUBBER SOUL — gunned down by REVOLVER 313 8: SGT PEPPERS & THE LOST SMILE 338 9: OLD SURFERS NEVER DIE, THEY JUST FADE AWAY 360 10: IF WE SING IN A VACUUM CAN YOU HEAR US? 378 AFTERWORD .........................................................................405 APPENDIX: BEACH BOYS HIT ALBUMS (1962-1970) ...411 BIBLIOGRAPHY....................................................................419 ix 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD Rock is a fickle mistress. -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

Concerto and Aria Concert May 14 & 15, 2021 7:00 P.M

Concerto and Aria Concert May 14 & 15, 2021 7:00 p.m. Online MacPhail Center for Music MacPhail Center for Music is a nonprofit organization providing life-changing music learning experiences to people of all ages and backgrounds. MacPhail connects with more than 60,000 people in our community annually, through music instruction, community partnerships and performance events. PROGRAM Friday, May 14, 2021 Violin Concerto in A minor, BWV 1041...................................................................................................................Johann Sebastian Bach I: Allegro II: Andante III: Allegro assai Eira Lindberg, violin Student of Mark Bjork Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37................................................................................................................Ludwig van Beethoven I: Allegro con brio Jackson Trom, piano Student of Suzanne Greer “Dove sono I bei momenti” from Le Nozze di Figaro (“The Marriage of Figaro”)............................Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Shannon Braun, voice Student of Mikyoung Park Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11...............................................................................................................................Frédéric Chopin Jessica Shao, piano Student of Jose Uriarte Saturday, May 15, 2021 Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 46........................................................................................................Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart I: Allegro Christian Garner, piano Student of Suzanne Greer “Hello! -

“Fascinating Facts” December 2017

Daily Sparkle CD - A Review of Famous Songs of the Past “Fascinating Facts” December 2017 Track 1 Chestnuts Roasting On An Open Fire The Christmas Song (commonly subtitled "Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire") is a classic Christmas song written in 1944 by musician, composer, and vocalist Mel Tormé and Bob Wells. According to Tormé, the song was written during a blistering hot summer. In an effort to "stay cool by thinking cool", the most-performed Christmas song was born. "I saw four lines written on a notepad", Tormé recalled. "They started, "Chestnuts roasting..., Jack Frost nipping..., Yuletide carols..., Folks dressed up like Eskimos.' Bob (Wells, co-writer) hadn’t thought he was writing a song lyric! He said he thought if he could immerse himself in winter he could cool off! Forty minutes later that song was written. Nathaniel Adams Coles (March 17, 1919 – February 15, 1965), known professionally as Nat King Cole, was an American musician who first came to prominence as a leading jazz pianist. He owes most of his popular musical fame to his soft baritone voice, which he used to perform in big band and jazz genres. He was one of the first black Americans to host a television variety show. Cole fought racism all his life and rarely performed in segregated venues. In 1948, Cole purchased a house in an all-white neighbourhood of Los Angeles. The Ku Klux Klan, still active in Los Angeles well into the 1950s, responded by placing a burning cross on his front lawn. Members of the property-owners association told Cole they did not want any undesirables moving in. -

INDEPENDENT AUSTRALIAN LABELS 1955 to 1990

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS INDEPENDENT AUSTRALIAN LABELS 1955 to 1990 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER OCTOBER 2019 AUSTRALIAN INDIE LABELS, 1955–1990 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS GRATEFUL THANKS TO: HANK B. FACER, FOR HIS ‘LOGO’ MUSEUM OF INDIGENOUS RECORDING LABELS, CHRIS SPENCER, FOR HIS AUSTRALIAN MUSIC MUSEUM, THE CONTRIBUTORS TO 45CAT.COM, DISCOGS.COM, RATEYOURMUSIC.COM AND MILESAGO, MARK GREGORY’S AUSTRALIAN FOLK SONGS WEBSITE AT FOLKSTREAM.COM THE NATIONAL FILM AND SOUND ARCHIVE, AND MUSIC AUSTRALIA, FOR THEIR ON-LINE CATALOGUES, ANDREW AINSWORTH, ALISTAIR BANFIELD, HARRY BUTLER, BILL CASEY, HEDLEY CHARLES, MICHAEL DEN HARTOG, DAVID HUGHES, DAVID KENT, ROSS LAIRD, JACK MITCHELL, IAN D. ROSS, GJERMUND SKOGSTAD, BRIAN WAFER, AND CLINTON WALKER LATE, GREAT COLLEAGUES GEORGE CROTTY, DEAN MITTELHAUSER, RON SMITH AND MIKE SUTCLIFFE FOR THEIR LOVE OF AUSTRALIAN MUSIC AND FOR THEIR PIONEERING RESEARCH. SOME PRESSING INFORMATION NUMBERS OR LETTERS PRINTED ON THE RECORD LABEL OR INSCRIBED IN THE RUN-OFF WAX OFTEN GIVES CLUES ABOUT WHICH RECORD COMPANY PRESSED THE RECORD, AND WHEN IT WAS PRESSED. TYPICAL PREFIXES INCLUDE: 7XS EMI CUSTOM RECORDING AW RADIOLA/AWA CUSTOM RECORDING CWG W&G CUSTOM RECORDING DB RCA DOTTED TRIANGLE SHEARD & CO. FH ASTOR MA ASTOR CUSTOM PRESSING MX FESTIVAL, OR AUSTRALIAN RECORD COMPANY / CBS PRS, YPRX EMI CUSTOM RECORDING RRC, RRCS RANGER CUSTOM RECORDING SMX FESTIVAL 2 AUSTRALIAN INDIE LABELS, 1955–1990 CAT. NO. TITLE(S) FORMAT / MX NO. / NOTES ARTIST(S) DATE 3333 RECORDS DISTRIBUTED BY MUSICLAND. MUSLP 3333 LIVE AT SING SING LP THE BACHELORS FROM PRAGUE 1986 3333/1 THE ENERGETIC COOL CD THE BACHELORS FROM PRAGUE 5.88 MUS SP 3333/2 GO / EVEN DISHWASHERS GET THE BLUES BACHELORS FROM PRAGUE 9.88 3333/3 THE ENERGETIC COOL LP THE BACHELORS FROM PRAGUE 1988 SP 3333/3 TIGHTROPE / THE OUTSIDER 7” BACHELORS FROM PRAGUE 3.89 TO MERCURY RECORDS, THROUGH PHONOGRAM AARON RECORDS PB 0001 MAMA / THAT LUCKY OLD SUN DAVID J. -

The Chart Book – Albums the NME Album Charts

The Chart Book – Albums The NME Album Charts Volume 1 - 1962-1969 Compiled by Lonnie Readioff Contents Introduction Introduction ............................................................................................. 2 The New Musical Express may have begun the Singles chart (in 1952), but they where the last to Chart Milestones ...................................................................................... 3 the party in terms of creating an Album chart, only starting a Top 10 in 1962. Even then, albums would still chart on the main Singles chart, when sales we’re sufficiently large (Noticeably the The Artist Section ..................................................................................... 4 Beatles and the Rolling Stones achieved this). Having said this though, NME was sampling a Analysis Section ....................................................................................... 71 larger array of shops than the chart now considered the Official one fo the 1960’s, and so this Most Weeks On Chart By Artist ........................................................... 72 chart – together with Melody Maker – are equally merits of the position of “National” chart for Most Weeks On Chart By Year ............................................................ 74 the 1960’s. Most Weeks On Chart By Record ........................................................ 77 The small chart size here was simply all that NME decided to produce, and indeed it would be The Number 1’s ....................................................................................... -

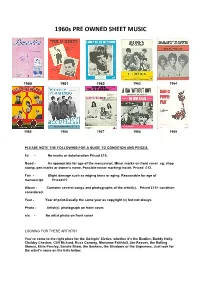

1960S PRE OWNED SHEET MUSIC

1960s PRE OWNED SHEET MUSIC 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR A GUIDE TO CONDITION AND PRICES. Ex - No marks or deterioration.Priced £15. Good - As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Minor marks on front cover eg. shop stamp, pen marks or owner's name. Possible minor marking inside. Priced £12. Fair - Slight damage such as edging tears or aging. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album - Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered. Year - Year of print.Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo - Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a - No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS? You’ve come to the right place for the Swingin’ Sixties, whether it’s the Beatles, Buddy Holly, Chubby Checker, Cliff Richard, Russ Conway, Marianne Faithfull, Jim Reeves, the Rolling Stones, Elvis Presley, Sandie Shaw, the Seekers, the Shadows or the Supremes. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. Title Writer and Composer condition Photo Year 19th Nervous Mick Jagger/Keith Richard ex The Rolling Stones 1966 breakdown 59th Street Paul Simon ex Harpers Bizarre or 1967 bridge song Paul Simon (Feelin‟ groovy) A Banda Chico Buarque de Hollanda fair Herb Alpert 1966 Acapulco Greenslade/Allan good Kenny Ball 1962 1922 Acapulco Eldon Allan/Shel Talmy good Kathy Kirby/Johnny B. 1962 1922 (vocal Great version) A clown am I Winifred Atwell ex Johnny Hackett 1967 Adios, Ralph Freed/Jerry Livingston ex Jim Reeves 1962 amigo -

The Hi-Fi's Gig List of Artists Supported Should Any Other Names Be Remembered by Anyone Then Please Contact Us Through the Website

The Hi-Fi's Gig List of Artists Supported Should any other names be remembered by anyone then please contact us through the website Artists supported on same bill when where ADAM FAITH & THE ROULETTES Apr-61 Waltham Cross + other venues upto 1963 ADAM WADE 1961 Hackney 59 club ALAN KENNON & THE SUNLIGHTERS Dec-62 Croydon ABC Cinema ARTHUR GREENSLADE & THE G MEN May-64 Saturday Club BBC radio show No 323 B BUMBLE & THE STINGERS Apr-62 Waltham Cross BIG DEE IRWIN 1965 Package tour BILLY FURY 1962 Bletchley BILLY O'SULLIVAN Oct-58 The Alhambra, Bradford BOB & MARION KOYNOT Oct-58 The Alhambra, Bradford BOBBY ANGELO & the TUXEDOES Dec-61 South Norwood Stanley Halls BRIAN POOLE & THE TREMELOES 1960-63 A few times CARTER LEWIS & THE SOUTHERNERS Nov-63 Duane Eddy tour CAS TUREWICZ Jan-63 625 BBC TV show CHRIS FARLOWE & THE THUNDERBIRDS (ALBERT LEE lead guitar) 1959-60 Peckham Co-op and Putney Ballroom CLARENCE FROGMAN HENRY 1966 Tour dates unknown CLIFF RICHARD & THE DRIFTERS Jan-59 Cheam, Baths Surrey CYRYL DAVIES' ALLSTARS.ALEXIS KORNERS/LONG JOHN BALDRY/ERIC CLAPTON Aug-63 Liverpool Stadium DANNY STREET Mar-65 Ideal Home Exhibition personal appearance DEAN FORD & THE GAYLORDS (THE MARMALADE) Jun-63 Eyemouth DENNY PIERCY Mar-65 Ideal Home Exhibition personal appearance DILYS WATLING Mar-65 Ideal Home Exhibition personal appearance DIXIE CUPS Nov-64 All Stars Tour DOTTIE WEST Mar-65 Ideal Home Exhibition personal appearance DUANE EDDY Nov-63 Duane Eddy tour DUKE D'MONDE & THE BARRON KNIGHTS ? Date Dunstable California Ballroom EMILE FORD & -

Pop Music As a Possible Medium in Secondary Education (1966)

E:\M55\ARTICLES\Mcr1966.fm2001-12-19 17:01 Pop Music as a Possible Medium in Secondary Education (1966) by Philip Tagg Contents Foreword (2001) ... 2 Pop Music as a Possible Medium in Secondary Education ... 7 Introduction ... 7 What is popular music? ... 11 Social aspects of pop music ... 16 Pop music in secondary education ... 19 Summary ... 25 Appendices ... 27 1. Bibliography ... 27 2. Questionnaire details ... 27 3a. Survey scores (individual) ... 31 3b. Survey scores (averages) ... 33 Tagg: Pop music in secondary education (1966): Foreword (2001) 2 Foreword (2001) The text that follows was written thirty-five years ago. It was submitted at the end of the one-year Diploma in Education course I took at the University of Manchester in 1965-66. Fifteen years later, we founded the International Association for the Study of Popular Music (IASPM)1 and in the same year, 1981, the first issue of the Cambridge University Press journal Popular Music was published. Since then, popular music has made inroads into all stages of education. Seen from this perspective, the 1966 text has, I feel, some documentary value: although probably not the first text to make a case for popular music in education, it is to my knowledge one of the earliest written attempts to address the issue seriously. However, resurrecting this old text for web publication raises two obvious problems: [1] the world has changed a lot since 1966 and some of the ideas and arguments presented then need recontextualisation; [2] I was a very young man at the time and had little or no experience of social science meth- od; nor was I aware of the workings of capitalism or of its influence on sub- jectivity, on music, on the arts in general, or on education. -

PROCEEDINGS the 82Nd Annual Meeting 2006

PROCEEDINGS The 82nd Annual Meeting 2006 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC 11250 Roger Bacon Drive, Suite 21 Reston, Virginia 20190 Telephone: (703) 437-0700, Facsimile: (703) 437-6312 Web Address: www.arts-accredit.org E-mail: [email protected] NUMBER 95 SEPTEMBER 2007 PROCEEDINGS The 82nd Annual Meeting 2006 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC 11250 Roger Bacon Drive, Suite 21 Reston, Virginia 20190 Telephone: (703) 437-0700, Facsimile: (703) 437-6312 Web Address: www.arts-accredit.org E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2007 ISSN Number 0190-6615 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC 11250 ROGER BACON DRIVE, SUITE 21, RESTON, VA 20190 All rights reserved including the right to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form. CONTENTS Preface vii Keynote Address Weapons of Mass Instruction Nancy Smith Fichter 1 Future of Art Music: Teaching Music in General Studies—^Has the Time Come for Specialists? Teaching Music in General Studies—Has the Time Come for Specialists? Gerard Aloisio 11 Response to "Teaching Music in General Studies^—Has the Time Come for Specialists?" Robert Weirich 20 Leadership: Advocacy for Music in the Promotion and Tenure Process Leadership: Advocacy for Music in the Promotion and Tenure Process Georgia Cowart 25 Working Productively With the Cultural Impacts of Technology: the Challenges for Music Leaders in Academe Working Productively With the Cultural Impacts of Technology: the Challenges for Music Leaders in Academe Christopher Kendall 29 Working Productively With the Cultural Impacts -

Sed the Bachelors

RECORD MIRROR Week ending April II,106 RECORD MIRROR, Week ending, Aprilil,1064 8 EXCLUSIVE STORY ABOUT ACTRESSJANE ASHER AND HER BROTHER PETER, OF PETER& GORDON JANE ASHER SPEAKS... JANEASHER was justa really remember THAT. But few minutes late.She'd the song came up one night been rehearsing for an ITN, when Paul and John were DAVE CURTISS& "Love Sloe," Play which goes by round at our home. They out on May 5. She turned up hadn't really finished it, but in black leather coat, black Peter and Gordon were mad stockings ... and that mar. keen about it right away, THE TREMORS vellous streamofauburny. reddy hair shimmering PETER around her shoulders. NEVER ROW! Summertime She settled comfortably Blues for a coffee - "Flat, please." "So the boys worked on it. Lit a tipped cigarette. And JONES Oh, yes, they often asked my PHI TIPStetE 'DJ. glowed with enthusiasm as opinion. That's another odd shetalkedabout how her thing - peOPle seem to think brother Peter, along with his that a brother and sister long-time friend Gordon, had should be argUing and hav- crashed "World WithoutNo surnames.It's easier to ing rows. Well, we NEVER Love" to the chart summit. remember - and also it got have rows. We're really like "Honestly, it's marvellous,"away from my name.That friends. And Gordon ... well. SECRETS she said."Do you know itWas one thing that worriedI've known him a long time. could evengetto numberme. You know, all this talk He lives at Pinner, in Middle. kne? I'm so thrilled.I just aboutPaul McCartney and sex, along way from our w it would be a hit, even I.Well,Ithought the Sir's home, so he often stays over Rey BigBoy thoughIdidcriticisethewouldallhate me - and after they've been rehears- middle organ solo abit onthroughthatHATE poor ing.