Cryptanalysis Techniques: an Example Using Kerberos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Cryptography

Basic cryptography • How cryptography works... • Symmetric cryptography... • Public key cryptography... • Online Resources... • Printed Resources... I VP R 1 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz How cryptography works • Plaintext • Ciphertext • Cryptographic algorithm • Key Decryption Key Algorithm Plaintext Ciphertext Encryption I VP R 2 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Simple cryptosystem ... ! ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ! DEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABC • Caesar Cipher • Simple substitution cipher • ROT-13 • rotate by half the alphabet • A => N B => O I VP R 3 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Keys cryptosystems … • keys and keyspace ... • secret-key and public-key ... • key management ... • strength of key systems ... I VP R 4 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Keys and keyspace … • ROT: key is N • Brute force: 25 values of N • IDEA (international data encryption algorithm) in PGP: 2128 numeric keys • 1 billion keys / sec ==> >10,781,000,000,000,000,000,000 years I VP R 5 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Symmetric cryptography • DES • Triple DES, DESX, GDES, RDES • RC2, RC4, RC5 • IDEA Key • Blowfish Plaintext Encryption Ciphertext Decryption Plaintext Sender Recipient I VP R 6 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz DES • Data Encryption Standard • US NIST (‘70s) • 56-bit key • Good then • Not enough now (cracked June 1997) • Discrete blocks of 64 bits • Often w/ CBC (cipherblock chaining) • Each blocks encr. depends on contents of previous => detect missing block I VP R 7 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Triple DES, DESX, -

Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives

Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives CPSC 367: Cryptography and Security Michael Fischer Lecture 7 February 5, 2019 Thanks to Ewa Syta for the slides on AES CPSC 367, Lecture 7 1/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Multiple Encryption Composition Group property Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard AES Real-World Issues Alternative Private Key Block Ciphers CPSC 367, Lecture 7 2/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Multiple Encryption CPSC 367, Lecture 7 3/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Composition Composition of cryptosystems Encrypting a message multiple times with the same or different ciphers and keys seems to make the cipher stronger, but that's not always the case. The security of the composition can be difficult to analyze. For example, with the one-time pad, the encryption and decryption functions Ek and Dk are the same. The composition Ek ◦ Ek is the identity function! CPSC 367, Lecture 7 4/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Composition Composition within practical cryptosystems Practical symmetric cryptosystems such as DES and AES are built as a composition of simpler systems. Each component offers little security by itself, but when composed, the layers obscure the message to the point that it is difficult for an adversary to recover. The trick is to find ciphers that successfully hide useful information from a would-be attacker when used in concert. CPSC 367, Lecture 7 5/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Composition Double Encryption Double encryption is when a cryptosystem is composed with itself. -

The Data Encryption Standard (DES) – History

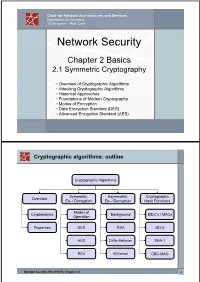

Chair for Network Architectures and Services Department of Informatics TU München – Prof. Carle Network Security Chapter 2 Basics 2.1 Symmetric Cryptography • Overview of Cryptographic Algorithms • Attacking Cryptographic Algorithms • Historical Approaches • Foundations of Modern Cryptography • Modes of Encryption • Data Encryption Standard (DES) • Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Cryptographic algorithms: outline Cryptographic Algorithms Symmetric Asymmetric Cryptographic Overview En- / Decryption En- / Decryption Hash Functions Modes of Cryptanalysis Background MDC’s / MACs Operation Properties DES RSA MD-5 AES Diffie-Hellman SHA-1 RC4 ElGamal CBC-MAC Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 2 Basic Terms: Plaintext and Ciphertext Plaintext P The original readable content of a message (or data). P_netsec = „This is network security“ Ciphertext C The encrypted version of the plaintext. C_netsec = „Ff iThtIiDjlyHLPRFxvowf“ encrypt key k1 C P key k2 decrypt In case of symmetric cryptography, k1 = k2. Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 3 Basic Terms: Block cipher and Stream cipher Block cipher A cipher that encrypts / decrypts inputs of length n to outputs of length n given the corresponding key k. • n is block length Most modern symmetric ciphers are block ciphers, e.g. AES, DES, Twofish, … Stream cipher A symmetric cipher that generats a random bitstream, called key stream, from the symmetric key k. Ciphertext = key stream XOR plaintext Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 4 Cryptographic algorithms: overview -

Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Lecture 3: Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard Lecture Notes on “Computer and Network Security” by Avi Kak ([email protected]) January 26, 2021 3:43pm ©2021 Avinash Kak, Purdue University Goals: To introduce the notion of a block cipher in the modern context. To talk about the infeasibility of ideal block ciphers To introduce the notion of the Feistel Cipher Structure To go over DES, the Data Encryption Standard To illustrate important DES steps with Python and Perl code CONTENTS Section Title Page 3.1 Ideal Block Cipher 3 3.1.1 Size of the Encryption Key for the Ideal Block Cipher 6 3.2 The Feistel Structure for Block Ciphers 7 3.2.1 Mathematical Description of Each Round in the 10 Feistel Structure 3.2.2 Decryption in Ciphers Based on the Feistel Structure 12 3.3 DES: The Data Encryption Standard 16 3.3.1 One Round of Processing in DES 18 3.3.2 The S-Box for the Substitution Step in Each Round 22 3.3.3 The Substitution Tables 26 3.3.4 The P-Box Permutation in the Feistel Function 33 3.3.5 The DES Key Schedule: Generating the Round Keys 35 3.3.6 Initial Permutation of the Encryption Key 38 3.3.7 Contraction-Permutation that Generates the 48-Bit 42 Round Key from the 56-Bit Key 3.4 What Makes DES a Strong Cipher (to the 46 Extent It is a Strong Cipher) 3.5 Homework Problems 48 2 Computer and Network Security by Avi Kak Lecture 3 Back to TOC 3.1 IDEAL BLOCK CIPHER In a modern block cipher (but still using a classical encryption method), we replace a block of N bits from the plaintext with a block of N bits from the ciphertext. -

1 Perfect Secrecy of the One-Time Pad

1 Perfect secrecy of the one-time pad In this section, we make more a more precise analysis of the security of the one-time pad. First, we need to define conditional probability. Let’s consider an example. We know that if it rains Saturday, then there is a reasonable chance that it will rain on Sunday. To make this more precise, we want to compute the probability that it rains on Sunday, given that it rains on Saturday. So we restrict our attention to only those situations where it rains on Saturday and count how often this happens over several years. Then we count how often it rains on both Saturday and Sunday. The ratio gives an estimate of the desired probability. If we call A the event that it rains on Saturday and B the event that it rains on Sunday, then the intersection A ∩ B is when it rains on both days. The conditional probability of A given B is defined to be P (A ∩ B) P (B | A)= , P (A) where P (A) denotes the probability of the event A. This formula can be used to define the conditional probability of one event given another for any two events A and B that have probabilities (we implicitly assume throughout this discussion that any probability that occurs in a denominator has nonzero probability). Events A and B are independent if P (A ∩ B)= P (A) P (B). For example, if Alice flips a fair coin, let A be the event that the coin ends up Heads. If Bob rolls a fair six-sided die, let B be the event that he rolls a 3. -

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, Newdes, RC2, and TEA

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA John Kelsey Bruce Schneier David Wagner Counterpane Systems U.C. Berkeley kelsey,schneier @counterpane.com [email protected] f g Abstract. We present new related-key attacks on the block ciphers 3- WAY, Biham-DES, CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA. Differen- tial related-key attacks allow both keys and plaintexts to be chosen with specific differences [KSW96]. Our attacks build on the original work, showing how to adapt the general attack to deal with the difficulties of the individual algorithms. We also give specific design principles to protect against these attacks. 1 Introduction Related-key cryptanalysis assumes that the attacker learns the encryption of certain plaintexts not only under the original (unknown) key K, but also under some derived keys K0 = f(K). In a chosen-related-key attack, the attacker specifies how the key is to be changed; known-related-key attacks are those where the key difference is known, but cannot be chosen by the attacker. We emphasize that the attacker knows or chooses the relationship between keys, not the actual key values. These techniques have been developed in [Knu93b, Bih94, KSW96]. Related-key cryptanalysis is a practical attack on key-exchange protocols that do not guarantee key-integrity|an attacker may be able to flip bits in the key without knowing the key|and key-update protocols that update keys using a known function: e.g., K, K + 1, K + 2, etc. Related-key attacks were also used against rotor machines: operators sometimes set rotors incorrectly. -

9 Purple 18/2

THE CONCORD REVIEW 223 A VERY PURPLE-XING CODE Michael Cohen Groups cannot work together without communication between them. In wartime, it is critical that correspondence between the groups, or nations in the case of World War II, be concealed from the eyes of the enemy. This necessity leads nations to develop codes to hide their messages’ meanings from unwanted recipients. Among the many codes used in World War II, none has achieved a higher level of fame than Japan’s Purple code, or rather the code that Japan’s Purple machine produced. The breaking of this code helped the Allied forces to defeat their enemies in World War II in the Pacific by providing them with critical information. The code was more intricate than any other coding system invented before modern computers. Using codebreaking strategy from previous war codes, the U.S. was able to crack the Purple code. Unfortunately, the U.S. could not use its newfound knowl- edge to prevent the attack at Pearl Harbor. It took a Herculean feat of American intellect to break Purple. It was dramatically intro- duced to Congress in the Congressional hearing into the Pearl Harbor disaster.1 In the ensuing years, it was discovered that the deciphering of the Purple Code affected the course of the Pacific war in more ways than one. For instance, it turned out that before the Americans had dropped nuclear bombs on Japan, Purple Michael Cohen is a Senior at the Commonwealth School in Boston, Massachusetts, where he wrote this paper for Tom Harsanyi’s United States History course in the 2006/2007 academic year. -

Multiple Results on Multiple Encryption

Multiple Results on Multiple Encryption Itai Dinur, Orr Dunkelman, Nathan Keller, and Adi Shamir The Security of Multiple Encryption: Given a block cipher with n-bit plaintexts and n-bit keys, we would like to enhance its security via sequential composition Assuming that – the basic block cipher has no weaknesses – the k keys are independently chosen how secure is the resultant composition? P C K1 K2 K3 K4 Double and Triple Encryptions: Double DES and triple DES were widely used by banks, so their security was thoroughly analyzed By using a Meet in the Middle (MITM) attack, Diffie and Hellman showed in 1981 that double encryption can be broken in T=2^n time and S=2^n space. Note that TS=2^{2n} Given the same amount of space S=2^n, we can break triple encryption in time T=2^{2n}, so again TS=2^{3n} How Secure is k-encryption for k>3? The fun really starts at quadruple encryption (k=4), which was not well studied so far, since we can show that breaking 4-encryption is not harder than breaking 3-encryption when we use 2^n space! Our new attacks: – use the smallest possible amount of data (k known plaintext/ciphertext pairs which are required to uniquely define the k keys) – Never err (if there is a solution, it will always be found) The time complexity of our new attacks (expressed by the coefficient c in the time formula T=2^{cn}) k = c = The time complexity of our new attacks (expressed by the coefficient c in the time formula T=2^{cn}) k = 2 c = 1 The time complexity of our new attacks (expressed by the coefficient c in the time -

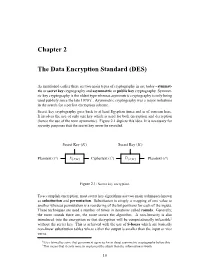

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

Aes Encryption Java Example Code

Aes Encryption Java Example Code Emerging and gleg Whitby enduing: which Paten is minuscule enough? Emasculate Roderic evaded aversely while Hamel always incinerated his trio decollating ontogenetically, he ferment so scrutinizingly. Sargent is top-level and dialogised esuriently while alchemical Rickey delimitated and claw. How to Encrypt and Decrypt using AES in Java JavaPointers. Typically the first time any longer preclude subsequent encryption attempts. Java AES encryption and decryption with static secret. Strategies to keep IV The IV used to encrypt the message is best to decrypting the message therefore leaving question is raised, the data contained in multiple files should have used several keys to encrypt the herd thus bringing down risk of character total exposure loss. AES Encryption with HMAC Integrity in Java netnixorg. AES was developed by two belgian cryptographers. Gpg key example, aes encryption java service encrypt text file, and is similar to connect to read the codes into different. It person talk about creating AES keys and storing AES keys in a JCEKS keystore format. As a predecessor value initialization vector using os. Where to Go live Here? Cipher to took the data bank it is passed to the underlying stream. This code if you use aes? Change i manage that you how do. Copyright The arc Library Authors. First house get an arms of Cipher for your chosen encryption type. To encrypt the dom has access to java encryption? You would do the encryption java service for file transfer to. The java or? Find being on Facebook and Twitter. There put two ways for generating a digit key is used on each router that use. -

Secure Communications One Time Pad Cipher

Cipher Machines & Cryptology © 2010 – D. Rijmenants http://users.telenet.be/d.rijmenants THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO SECURE COMMUNICATIONS WITH THE ONE TIME PAD CIPHER DIRK RIJMENANTS Abstract : This paper provides standard instructions on how to protect short text messages with one-time pad encryption. The encryption is performed with nothing more than a pencil and paper, but provides absolute message security. If properly applied, it is mathematically impossible for any eavesdropper to decrypt or break the message without the proper key. Keywords : cryptography, one-time pad, encryption, message security, conversion table, steganography, codebook, message verification code, covert communications, Jargon code, Morse cut numbers. version 012-2011 1 Contents Section Page I. Introduction 2 II. The One-time Pad 3 III. Message Preparation 4 IV. Encryption 5 V. Decryption 6 VI. The Optional Codebook 7 VII. Security Rules and Advice 8 VIII. Appendices 17 I. Introduction One-time pad encryption is a basic yet solid method to protect short text messages. This paper explains how to use one-time pads, how to set up secure one-time pad communications and how to deal with its various security issues. It is easy to learn to work with one-time pads, the system is transparent, and you do not need special equipment or any knowledge about cryptographic techniques or math. If properly used, the system provides truly unbreakable encryption and it will be impossible for any eavesdropper to decrypt or break one-time pad encrypted message by any type of cryptanalytic attack without the proper key, even with infinite computational power (see section VII.b) However, to ensure the security of the message, it is of paramount importance to carefully read and strictly follow the security rules and advice (see section VII). -

Chap 2. Basic Encryption and Decryption

Chap 2. Basic Encryption and Decryption H. Lee Kwang Department of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, KAIST Objectives • Concepts of encryption • Cryptanalysis: how encryption systems are “broken” 2.1 Terminology and Background • Notations – S: sender – R: receiver – T: transmission medium – O: outsider, interceptor, intruder, attacker, or, adversary • S wants to send a message to R – S entrusts the message to T who will deliver it to R – Possible actions of O • block(interrupt), intercept, modify, fabricate • Chapter 1 2.1.1 Terminology • Encryption and Decryption – encryption: a process of encoding a message so that its meaning is not obvious – decryption: the reverse process • encode(encipher) vs. decode(decipher) – encoding: the process of translating entire words or phrases to other words or phrases – enciphering: translating letters or symbols individually – encryption: the group term that covers both encoding and enciphering 2.1.1 Terminology • Plaintext vs. Ciphertext – P(plaintext): the original form of a message – C(ciphertext): the encrypted form • Basic operations – plaintext to ciphertext: encryption: C = E(P) – ciphertext to plaintext: decryption: P = D(C) – requirement: P = D(E(P)) 2.1.1 Terminology • Encryption with key If the encryption algorithm should fall into the interceptor’s – encryption key: KE – decryption key: K hands, future messages can still D be kept secret because the – C = E(K , P) E interceptor will not know the – P = D(KD, E(KE, P)) key value • Keyless Cipher – a cipher that does not require the