Dissertation Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Products Directory Kennet and Avon Canal Mike Robinson

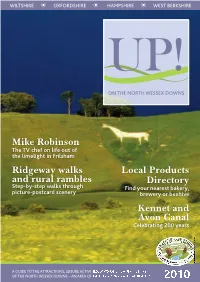

WILTSHIRE OXFORDSHIRE HAMPSHIRE WEST BERKSHIRE UP! ON THE NORTH WESSEX DOWNS Mike Robinson The TV chef on life out of the limelight in Frilsham Ridgeway walks Local Products and rural rambles Directory Step-by-step walks through Find your nearest bakery, picture-postcard scenery brewery or beehive Kennet and Avon Canal Celebrating 200 years A GUIDE TO THE ATTRACTIONS, LEISURE ACTIVITIES, WAYS OF LIFE AND HISTORY OF THE NORTH WESSEX DOWNS – AN AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY 2010 For Wining and Dining, indoors or out The Furze Bush Inn provides TheThe FurzeFurze BushBush formal and informal dining come rain or shine. Ball Hill, Near Newbury Welcome Just 2 miles from Wayfarer’s Walk in the elcome to one of the most beautiful, amazing and varied parts of England. The North Wessex village of Ball Hill, The Furze Bush Inn is one Front cover image: Downs was designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1972, which means of Newbury’s longest established ‘Food Pubs’ White Horse, Cherhill. Wit deserves the same protection by law as National Parks like the Lake District. It’s the job of serving Traditional English Bar Meals and an my team and our partners to work with everyone we can to defend, protect and enrich its natural beauty. excellent ‘A La Carte’ menu every lunchtime Part of the attraction of this place is the sheer variety – chances are that even if you’re local there are from Noon until 2.30pm, from 6pm until still discoveries to be made. Exhilarating chalk downs, rolling expanses of wheat and barley under huge 9.30pm in the evening and all day at skies, sparkling chalk streams, quiet river valleys, heaths, commons, pretty villages and historic market weekends and bank holidays towns, ancient forest and more.. -

Naturalist No

The Reading Naturalist No. 35 Published by the Reading and Di~trict Natural History Society 1983. Pri ce to Non-Members £1.00 Contents Page Meetings and ExcUrsions, 1981-82 .. ... 1 Presidential Addressg How to renew an interest in Carpentry · · B • . R. Baker 2 Hymenoptera in the neading Area H. Ho Carter 5 Wildlife Conservation at AWRE9 Aldermaston Ao Brickstock 10 Albinism in Frogs (Rana temporaria Lo ) 1978-82 j' A • . Price 12 . .t . Looking forward to the Spring So rlard 15 ';',' .. Kenfig Pool and Dunes, Glamorgan H. J. Mo Bowen 16 Mosses of Central Readingg Update Mo v. Fletcher 20 : "( Agaricus around Reading, 1982 P. Andrews 23 Honorary Recorders' Repor·ts g Fungi Ao Brickstock 27 Botany Bo H. Newman 32 .' ... 'EIl"tomology Bo Ro Baker 41 Vertebrat~s H. Ho Carter .. ... ·47 , Weather Records M. ' Parry ·· 51 Monthly vleather Notes Mo· Parry 52 Members' List 53 T3 E READIN"G NATU!tALIST The Journal of' .. " The Reading and District Natural His-t-ory Soci.ety President ~ Hon. General Secretaryg Hon-. Editor: Mrs. S. J. lihitf'ield Miss L. E. Cobb Editorial Sub-Committee: Miss E. M. Nelmes, Miss S. Y. Townend Honorary Recorders~ Botany; Hrs " B. M," NelYman 9 Mr. B. R. Baker, Vertebrates ~. Mr. H . H v Carter, Fungi: Dr. A. Brickstock, : .. - , 1 - The Annual General Meeting on 15th October 1981 (attendance 52) was ::followed by 'Mr. B. R. Baker's Presid ential Address entitled 'How to Renew an Interest in Carpentry' • A Natural History 'Brains Trust' (54) was held on 29th October under the chairmanship of the President, the members of the panel being Mr. -

In This Issue: Speech Day 10

Soundwave 2016 The Mary Hare Magazine June 2016 maryhare.org.ukmaryhare.org.uk In this issue: Speech Day 10 HRH Princess Royal visits 17 Sports Day 28 Ski Trip 44 Hare & Tortoise Walk 51 Head Boy & Head Girl 18 Primary News 46 SLT & Audiology 53 1 Soundwave 2016 The Mary Hare Magazine June 2016 maryhare.org.uk Acknowledgements Contents Editors, Gemma Pryor and Sammie Wilkinson Looking back and looking forward The Mary Hare Year 4–20 by Peter Gale Getting Active 21–28 Cole’s Diner 29–30 Welcome to this wonderful edition of Soundwave – Mr Peter Gale a real showcase of the breadth and diversity of experiences Arts News 31–33 which young people at Mary Hare get to enjoy. I hope you Helping Others 34–35 will enjoy reading it. People News 35–39 This has been a great year but joined us for our whole school under strict control and while Our Principal one with a real sadness at its sponsored walk/run and a they are substantial, they only Alumni 40–41 heart – the death of a member recent visit from Chelsea allow us to keep going – to of staff. Lesley White made a Goalkeeper Asmir Begovic who pay the wages and heat the Getting Around 42–45 huge contribution to Mary Hare presented us with a cheque school and to try to keep on and there is a tribute to her on for £10,000 means that the top of the maintenance of two Mary Hare Primary School 46–48 page 39. swimming pool Sink or Swim complex campuses. -

Local Cycling & Walking Infrastructure Plan

Local Cycling & Walking Infrastructure Plan LCWIP 1 Contents Foreword 3 1 Introduction 4 2 Integration with Active Travel Policy 7 3 Active Travel context 9 4 Network planning for cycling 14 5 Network planning for walking 24 6 Infrastructure improvements 26 7 Prioritisation, integration and next steps 30 Appendicies Appendix A Summary of Relevant Policy and Guidance 32 Appendix B Cycle Route Network Plans 36 Appendix C Eastern Area Cycle Routes 39 – Audit Key Findings and Recommended Improvements Appendix D Newbury and Thatcham Prioritised 42 Strategic Cycle Routes – Audit Key Findings and Recommended Improvements Appendix E Newbury and Thatcham 69 Key Walking Route Network Plan Appendix F Newbury and Thatcham Prioritised 70 Key Walking Routes – Audit Key Findings and Recommended Improvements 2 LCWIP Foreword West Berkshire Council is pleased to present our district. This joined-up approach covered our Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure cross-boundary routes and commuter zones on Plan (LCWIP) to act as a blueprint for future the urban fringe of Reading. We have adopted active travel routes in our district. It sets our a similar approach identifying walking and ambition to create a network of high-quality cycling routes in the settlements of Newbury interconnected cycle routes and walking zones and Thatcham and this report will prioritise the to encourage greater uptake of sustainable improvements of both urban areas together in travel modes. a comprehensive strategy for investment. By adopting the long-term approach provided The LCWIP has focused on identifying key by the LCWIP we can ensure that planning corridors connecting residential areas (both policy, public health, highway improvements, existing and proposed) to destinations such regeneration and developments are better as town centres, local centres, schools, linked to a coherent strategy that will employment sites and transport hubs. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

Greenham and Crookham Plataeu

Greenham and Crookham Plataeu Encompasses the whole plateau from Brimpton to Greenham and the slopes along the Kennet Valley in the north and the River Enborne in the south and east. Includes some riverside land along the Enborne in the south, where the River forms the boundary. Extends west to include a group of woodlands at Sandleford. Joint Character Area: Thames Basin Heaths Geology: The plateau has a large area of Silchester Gravel the overlies London Clay Sand (Bagshot Beds) which is found in a band at the edge of the Gravel. There are also some areas of Head at the edge of the top of the plateau. The slopes are London Clay Formation clay, silt and sand. There is alluvium along the Enborne Valley. The western section has a similar geology with Silchester Gravel, London Clay Sand ad London Clay Formation. Topography: a flat plateau that slopes away to river valleys in the north, south and east. The western area is the south facing slope at the edge of the plateau as it extends westwards into the developed land at Wash Common. Biodiversity: · Heathland and acid grassland: Extensive heathland and acid grassland areas at Greenham Common with small areas at Bowdown Woods and remnants at the mainly wooded Crookham Common and at Greenham Golf Course. · Lowland Mixed Deciduous Woodland: Extensive areas on the plateau slopes. Bowdown Woods and the areas within Greenham Common SSSI. · Wet Woodland: found in the gullies on the slopes at the plateau edge. · Other habitat and species: farmland near Brimpton supports good populations of farmland birds. -

Greenham Common Bulletin

Greenham Berkshire Buckinghamshire Common Bulletin Oxfordshire Managing your common for you 2nd Edition, winter 2015/16 Take the Wild Ride for Wildlife Crookham Commons. Wild Ride for Wildlife challenge! Cycle from Greenham The Wild Ride for Wildlife is being 8 to 11 September 2016 Common to Paris and raise funds organised by experienced event 200 miles for local nature reserves managers, Global Adventure Challenges. 3 days cycling Sign up to the 200-mile Wild Ride for Seasoned long-distance cyclists and Accommodation provided Wildlife from Greenham Common to enthusiasts who would like to take on Minimum sponsorship £1,300 Paris, and help to protect the amazing the challenge can find out more at a birds, flowers, reptiles and insects of West Wild Ride Information Evening on the 27 Berkshire. January at the Nature Discovery Centre in Thatcham. The Wild Ride for Wildlife will take place in September 2016, but cyclists are For more information visit: encouraged to sign up now to start bbowt.org.uk/wildride fundraising and training for the ride Contact the Fundraising Team on through southern England and northern [email protected] France. or 01865 775476. Funds raised on the Wild Ride for Wildlife will help us to look after heathland E W RID nature reserves such as Greenham and ILD Wallington Adrian for Wildlife Grazing on Greenham Common attle have been present on the ownership. A total of 50 active badger commons since 2001 and are setts have so far been recorded and to owned and grazed using historical date we have vaccinated 29 badgers C 2 commoners’ rights. -

Rides Flier 2018

Free social bike rides in the Newbury area Date Ride DescriptionRide Distance Start / Finish Time NewburyNewbury - Crockham - Wash Common Heath - - West Woolton Woodhay Hill - - West Mills beside 0503 Mar 1911 miles 09:30 Inkpen - Marsh BallBenham Hill - -Newbury Woodspeen - Newbury Lloyds Bank Newbury - BagnorKintbury - Chieveley- Hungerford - World's Newtown End - West Mills beside 1917 Mar 2027 miles 09:30 HermitageEast Garston - Cold Ash- Newbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Greenham - Woodspeen - Headley - Boxford -Kingsclere - - West Mills beside 072 Apr Apr 2210 miles 09:30 BurghclereWinterbourne - Crockham - HeathNewbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Crockham - Watership Heath Down - Kintbury - Whitchurch - Hungerford - - West Mills beside 1621 Apr 2433 miles 09:30 HurstbourneWickham Tarrant - Woodspeen - Woodhay - Newbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Cold - Enborne Ash - Hermitage - Marsh Benham - Yattendon - - West Mills beside 0507 May 2511 miles 09:30 HermitageStockcross - World's End - Bagnor - Winterbourne - Newbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Greenham - Highclere - Ecchinswell - Stoke - Ham - Inhurst - - West Mills beside 1921 May 3430 miles 09:30 Chapel Row -Inkpen Frilsham - Newbury - Cold Ash - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Crockham - Wash Heath Common - Faccombe - Woolton - Hurstbourne Hill - West Mills beside 024 Jun Jun 1531 miles 09:30 Tarrant East- Crux & EastonWest Woodhay - East Woodhay - Newbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank JohnNewbury Daw -Memorial Boxford - Ride Brightwalton -

APPENDIX G SALT BINS on the PUBLIC HIGHWAY (West Berkshire Council Owned)

APPENDIX G SALT BINS ON THE PUBLIC HIGHWAY (West Berkshire Council Owned) These bins are under the stewardship of Town and Parish Councils Parish/Town Road Location No. Ashampstead Noakes Hill Opposite "Noakes Hill" Cottage on other side of road 1 Ashampstead Palmers Hill At right corner of opening into field between 1 "Stubbles" and "Leyfield" cottages Ashampstead Pykes Hill Near the top of the hill on the sharp bend. 1 Basildon Kiln Ride Adjacent access to “Kiln Cottage” 1 Beech Hill Wood Lane Outside Beech Hill House 1 Beedon Mount Pleasant At top of hill on verge opposite Nos.17 and 18 1 Beedon Stanmore Road Between South Stanmore Farm & Halfpenny Catch 1 Lane Beedon Westons Junction with Stanmore Road 1 Beenham Cods Hill Approx. 50m North of Golf Course entrance 1 Beenham Lambdens Hill Near Lambdens Hill Cottages 1 Bradfield Bishops Road Junction with Mariners Lane 1 Bradfield Bishops Road Junction with Rotten Row Hill 1 Bradfield Cock Lane From South End Rd. 200m past Heath Rd. on right 1 hand side Bradfield Hungerford Lane Grass verge (Opposite Woodpecker Cottage) 1 Bradfield Rotten Row Junction with Mariners Lane 1 Bradfield Rotten Row Entrance to Bradfield Hall 1 Brightwalton Common Lane Opposite “Keepers Cottage” 1 Brightwalton Holt Lane Approx. 600m from Pudding Lane 1 Brimpton Hyde End Lane Adjacent Upper Hyde End Farm 1 Bucklebury Briff Lane On verge opposite Greenacres 1 Bucklebury Sadgrove Lane On verge opposite Paxton House 1 Bucklebury The Slade Just above the houses in The Slade 1 Burghfield Auclum Close Outside The -

Former Gama Site, Greenham Common, Near Newbury, Berkshire Rg14 7Hq

FORMER GAMA SITE, GREENHAM COMMON, NEAR NEWBURY, BERKSHIRE RG14 7HQ The boundary highlighted above in red is for guidance purposes only. Potential purchasers should satisfy themselves as to the accuracy of the site boundaries. FORMER GAMA SITE, GREENHAM COMMON, NEAR NEWBURY, BERKSHIRE RG14 7HQ. ◆ Former Ground Launched Cruise Missile Alert and Maintenance Area ◆ SPV with freehold for sale, with full vacant possession, no rights of way or easements ◆ Gross site area extending to approximately 73.85 acres (29.89 hectares) ◆ Planning consent for the storage of over 6,000 cars. Suitable for alternative uses subject to planning and scheduled monument consent ◆ Probably the most secure above ground storage available in 6 former nuclear bunkers with additional hardened buildings totalling over 75,000 sq. ft ◆ Opportunity to own a site deemed of national importance Location Newbury is a prosperous Thames Valley town on the River Kennet, 16 miles west of Reading and 8 miles north-west of Basingstoke. The town benefits from its proximity to the M4 Motorway (junction 13, 4miles) to the North and 3 miles from A34 dual carriageway, a major north-south arterial route which can be accessed via the B4640 at Tothill Services. The M3 at Basingstoke is approx. 8 miles Southeast. The property is situated less than 2 miles to the south-east of Newbury town centre and was formerly part of RAF Greenham Common which is now disused. The majority of the former air field buildings now comprise the new Greenham Park Business Park a short distance to the east whilst the remainder of the airfield is now vested in the local authority, West Berkshire District Council. -

Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd

T H A M E S V A L L E Y ARCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S Land east of Greenham Road, Greenham, Newbury, Berkshire Archaeological Evaluation by Pierre Manisse Site Code: GHG16/113 (SU 4815 6570) Land east of Greenham Road, Greenham, Newbury, Berkshire An Archaeological Evaluation for David Wilson Homes Southern Ltd by Pierre-Damien Manisse Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code GHG 16/113 July 2018 Summary Site name: Land east of Greenham Road, Greenham, Newbury, Berkshire Grid reference: SU 4815 6570 Site activity: Archaeological Evaluation Date and duration of project: 25th June - 2nd July 2018 Project Manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Pierre-Damien Manisse Site code: GHG 16/113 Area of site: 4.23ha Summary of results: Twenty trenches were excavated, with five containing certain or probable features of archaeological interest. These consisted of linear features, interpreted as field boundaries. Two are possibly of Roman or Medieval date, with the others undated. Apart from these features, it is considered that the archaeological potential of the site is low. Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at Thames Valley Archaeological Services, Reading and will be deposited with West Berkshire Museum, Newbury, with an accession number assigned in due course. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. All TVAS unpublished fieldwork reports are available on our website: www.tvas.co.uk/reports/reports.asp. Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford 10.07.18 i Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 47–49 De Beauvoir Road, Reading RG1 5NR Tel. -

Local Wildife Sites West Berkshire - 2021

LOCAL WILDIFE SITES WEST BERKSHIRE - 2021 This list includes Local Wildlife Sites. Please contact TVERC for information on: • site location and boundary • area (ha) • designation date • last survey date • site description • notable and protected habitats and species recorded on site Site Code Site Name District Parish SU27Y01 Dean Stubbing Copse West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU27Z01 Baydon Hole West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU27Z02 Thornslait Plantation West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU28V04 Old Warren incl. Warren Wood West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU36D01 Ladys Wood West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36E01 Cake Wood West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36H02 Kiln Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36H03 Elm Copse/High Tree Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36M01 Anville's Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36M02 Great Sadler's Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M07 Totterdown Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M09 The Fens/Finch's Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M15 Craven Road Field West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36P01 Denford Farm West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36P02 Denford Gate West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36P03 Hungerford Park Triangle West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36P04.1 Oaken Copse (east) West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36P04.2 Oaken Copse (west) West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36Q01 Summer Hill West Berkshire Council Combe SU36Q03 Sugglestone Down West Berkshire Council Combe SU36Q07 Park Wood West Berkshire Council Combe SU36R01 Inkpen and Walbury Hills West