Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. LISTA CANDIDATURAS PT.Xlsx

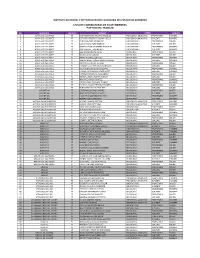

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO LISTA DE CANDIDATURAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS PARTIDO DEL TRABAJO NO. MUNICIPIO PARTIDO NOMBRE CARGO GÉNERO 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT IGOR ALEJANDRO AGUIRRE VAZQUEZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 2 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT OCTAVIO ROBERTO GALEANA BELLO PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL SUPLENTE HOMBRE 3 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT JENNY SANCHEZ RODRIGUEZ SINDICATURA 1 PROPIETARIA MUJER 4 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT KARLA PAOLA HARO MARCIAL SINDICATURA 1 SUPLENTE MUJER 5 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT ROBERTO CARLOS ORTEGA GONZALEZ SINDICATURA 2 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 6 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT JOSÉ MANUEL LEON BRUNO SINDICATURA 2 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 7 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT ANA IRIS MENDOZA NAVA REGIDURIA 1 PROPIETARIA MUJER 8 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MAYRA LEON CASIANO REGIDURIA 1 SUPLENTE MUJER 9 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MARIO ALONSO QUEVEDO REGIDURIA 2 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 10 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT SANTOS ANGEL TOMAS ANALCO RAMOS REGIDURIA 2 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 11 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT LILIANA ESTEVEZ DE LA ROSA REGIDURIA 3 PROPIETARIA MUJER 12 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT DANELLY ESTEFANY ROMERO NAJERA REGIDURIA 3 SUPLENTE MUJER 13 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT REGINALDO LARREA BALTODANO REGIDURIA 4 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 14 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT CARLOS ALEJANDRO CHAVEZ LOPEZ REGIDURIA 4 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 15 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT DAYANA YIZEL NAVA AVELLANEDA REGIDURIA 5 PROPIETARIA MUJER 16 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MAYRA LUCILA CADENA AGUILAR REGIDURIA 5 SUPLENTE MUJER 17 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MAURICIO SUAZO BENITEZ REGIDURIA 6 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE -

9. LISTA CANDIDATURAS RSP.Xlsx

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO LISTA DE CANDIDATURAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS REDES SOCIALES PROGRESISTAS NO. MUNICIPIO PARTIDO NOMBRECARGO GÉNERO 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP PATRICIA MANZANO RESENDIZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL PROPIETARIA MUJER 2 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP ELIZABETH MALDONADO RAMIREZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL SUPLENTE MUJER 3 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP CARLOS IGNACIO GARCIA VALVERDE SINDICATURA 1 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 4 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP JOSE LUIS ZAMORA NOLASCO SINDICATURA 1 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 5 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP BEATRIZ CORTES CHAVARRIA SINDICATURA 2 PROPIETARIA MUJER 6 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP MELANI VARGAS RUIZ SINDICATURA 2 SUPLENTE MUJER 7 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP VICENTE AVILA ORTIZ REGIDURIA 1 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 8 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP SERGIO VALVERDE ORTIZ REGIDURIA 1 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 9 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP KARLA YANETH NAVA TAPIA REGIDURIA 2 PROPIETARIA MUJER 10 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP YULIETH GOMEZ MAYO REGIDURIA 2 SUPLENTE MUJER 11 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP OLIVER ALEXIS ALCOCER MANZANO REGIDURIA 3 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 12 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP EDUARDO GONZALEZ TERESA REGIDURIA 3 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 13 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP KATHYA ALEJANDRA MAYORGA RAMIREZ REGIDURIA 4 PROPIETARIA MUJER 14 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP SARAI ABIGAIL GARCIA DE DIOS REGIDURIA 4 SUPLENTE MUJER 15 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP MOISES ARMANDO VALLE PAREDES REGIDURIA 5 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 16 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ RSP DAVID LOPEZ LOZANO REGIDURIA 5 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 17 ATOYAC DE ÁLVAREZ RSP BERNARDO NERI BENITEZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL PROPIETARIO -

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

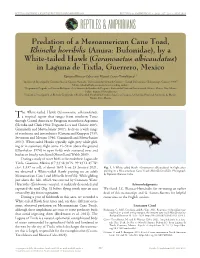

HTTPS://JOURNALS.KU.EDU/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANSREPTILES • VOL & AMPHIBIANS15, NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 28(2):189 227–228 • AUG 2021 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS PredationFEATURE ARTICLES of a Mesoamerican Cane Toad, . Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: RhinellaOn the Road tohorribilis Understanding the Ecology and Conservation(Anura: of the Midwest’s GiantBufonidae), Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190by a . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: White-tailedA Hypothetical Excursion Hawk ............................................................................................................................ (Geranoaetus albicaudatusRobert W. Henderson 198 ) RESEARCH ARTICLES in. The Laguna Texas Horned Lizard in Central de and Western Tixtla, Texas ....................... EmilyGuerrero, Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, M and Gade Perryxico 204 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida .............................................Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 Epifanio Blancas-Calva1 and Marisol Castro-Torreblanca2, 3 CONSERVATION ALERT 1Instituto de Investigación Científica Área de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero, Ciudad Universitaria, Chilpancingo, Guerrero 39087, . World’s Mammals in Crisis ...............................................................................................................................Mexico -

Orden Del Día

PASE DE LISTA DE ASISTENCIA. *DECLARATORIA DE QUÓRUM. ORDEN DEL DÍA 1.-COMUNICADOS: a) OFICIO SIGNADO POR EL LICENCIADO BENJAMÍN GALLEGOS SEGURA, SECRETARIO DE SERVICIOS PARLAMENTARIOS, CON EL QUE INFORMA DE LA RECEPCIÓN DE LOS SIGUIENTES ASUNTOS: I. OFICIO SUSCRITO POR LA CIUDADANA ANTARES GUADALUPE VÁZQUEZ ALATORRE, SENADORA SECRETARIA DE LA MESA DIRECTIVA DE LA CÁMARA DE SENADORES DEL CONGRESO DE LA UNIÓN, POR MEDIO DEL CUAL HACE DEL CONOCIMIENTO DEL PUNTO DE ACUERDO POR EL QUE EL SENADO DE LA REPÚBLICA EXHORTA, A LA SECRETARÍA DE HACIENDA Y CRÉDITO PÚBLICO, PARA QUE, EN EL ÁMBITO DE SUS ATRIBUCIONES, ANALICE Y EN SU CASO, REALICE LAS ACCIONES CORRESPONDIENTES, PARA ATENDER LA PROBLEMÁTICA DE LOS PASIVOS LABORALES QUE PRESENTAN LAS UNIVERSIDADES PÚBLICAS DEL PAÍS Y SE GARANTICEN LOS DERECHOS LABORALES DE LOS TRABAJADORES, ASÍ COMO LA IMPARTICIÓN EDUCATIVA Y EL FUNCIONAMIENTO DE DICHAS INSTITUCIONES. II. OFICIO SIGNADO POR EL DIPUTADO JOSÉ DE JESÚS MARTÍN DEL CAMPO CASTAÑEDA, PRESIDENTE DE LA MESA DIRECTIVA DEL CONGRESO DE LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, CON EL QUE REMITE BANDO SOLEMNE PARA DAR A CONOCER LA DECLARATORIA DE TITULAR DE LA JEFATURA DE GOBIERNO DE LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO ELECTA DE LA CIUDADANA CLAUDIA SHEINBAUM PARDO, PARA EL PERIODO DEL 05 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2018 AL 04 DE OCTUBRE DE 2024. III. OFICIO SUSCRITO POR LOS DIPUTADOS FERNANDO LEVIN ZELAYA ESPINOZA Y ADRIANA DEL ROSARIO CHAN CANUL, PRESIDENTE Y SECRETARIA DEL HONORABLE CONGRESO DEL ESTADO DE QUINTANA ROO, MEDIANTE EL CUAL REMITE COPIA DEL ACUERDO POR EL QUE SE EXHORTA ATENTA COMO RESPETUOSAMENTE AL TITULAR DEL PODER EJECUTIVO FEDERAL, AL HONORABLE CONGRESO DE LA UNIÓN Y AL SECRETARIO DE TURISMO DEL PAÍS, A EFECTO DE QUE SE CONTINÚE FORTALECIENDO Y SE MANTENGA EL RECURSO PARA LA PROMOCIÓN DE LOS DESTINOS TURÍSTICOS DEL ESTADO, A TRAVÉS DE LAS DISTINTAS FERIAS, TIANGUIS DE TURISMO Y EVENTOS DEPORTIVOS DE TALLA INTERNACIONAL QUE SE CELEBRAN EN EL ESTADO. -

Directorio De Oficialías Del Registro Civil

DIRECTORIO DE OFICIALÍAS DEL REGISTRO CIVIL DATOS DE UBICACIÓN Y CONTACTO ESTATUS DE FUNCIONAMIENTO POR EMERGENCIA COVID19 CLAVE DE CONSEC. MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE OFICIALÍA NOMBRE DE OFICIAL En caso de ABIERTA o PARCIAL OFICIALÍA DIRECCIÓN HORARIO TELÉFONO (S) DE CONTACTO CORREO (S) ELECTRÓNICO ABIERTA PARCIAL CERRADA Días de atención Horarios de atención 1 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ ACAPULCO 1 ACAPULCO 09:00-15:00 SI CERRADA CERRADA LUNES, MIÉRCOLES Y LUNES-MIERCOLES Y VIERNES 9:00-3:00 2 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ TEXCA 2 TEXCA FLORI GARCIA LOZANO CONOCIDO (COMISARIA MUNICIPAL) 09:00-15:00 CELULAR: 74 42 67 33 25 [email protected] SI VIERNES. MARTES Y JUEVES 10:00- MARTES Y JUEVES 02:00 OFICINA: 01 744 43 153 25 TELEFONO: 3 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ HUAMUCHITOS 3 HUAMUCHITOS C. ROBERTO LORENZO JACINTO. CONOCIDO 09:00-15:00 SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-05:00 01 744 43 1 17 84. CALLE: INDEPENDENCIA S/N, COL. CENTRO, KILOMETRO CELULAR: 74 45 05 52 52 TELEFONO: 01 4 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ KILOMETRO 30 4 KILOMETRO 30 LIC. ROSA MARTHA OSORIO TORRES. 09:00-15:00 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-04:00 TREINTA 744 44 2 00 75 CELULAR: 74 41 35 71 39. TELEFONO: 5 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PUERTO MARQUEZ 5 PUERTO MARQUEZ LIC. SELENE SALINAS PEREZ. AV. MIGUEL ALEMAN, S/N. 09:00-15:00 01 744 43 3 76 53 COMISARIA: 74 41 35 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-02:00 71 39. 6 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PLAN DE LOS AMATES 6 PLAN DE LOS AMATES C. -

Guía Técnica De La Ley De Ingresos Municipal

LA SEXAGÉSIMA SEGUNDA LEGISLATURA AL HONORABLE CONGRESO DEL ESTADO LIBRE Y SOBERANO DE GUERRERO, EN NOMBRE DEL PUEBLO QUE REPRESENTA, Y: C O N S I D E R A N D O Que en sesión de fecha 10 de diciembre del 2019, la Diputada y los Diputados integrantes de la Comisión de Hacienda, presentaron a la Plenaria el Dictamen con Proyecto de Ley de Ingresos para el Municipio de Tlacoachistlahuaca, Guerrero, para el Ejercicio Fiscal 2020, en los siguientes términos: “METODOLOGÍA DE TRABAJO La Comisión realizó el análisis de esta Iniciativa con proyecto de Ley conforme al procedimiento que a continuación se describe: En al apartado de “Antecedentes Generales” se describe el trámite que inicia el proceso legislativo, a partir de la fecha en que fue presentada la Iniciativa ante el Pleno de la Sexagésima Segunda Legislatura al Honorable Congreso del Estado Libre y Soberano de Guerrero. En el apartado denominado “Consideraciones” los integrantes de la Comisión Dictaminadora realizan una valoración de la iniciativa con base al contenido de los diversos ordenamientos legales aplicables. En el apartado referido al “Contenido de la Iniciativa”, se hace una descripción de la propuesta sometida al Pleno de la Sexagésima Segunda Legislatura al Honorable Congreso del Estado Libre y Soberano de Guerrero, incluyendo la Exposición de Motivos. En el apartado de “Conclusiones”, el trabajo de esta Comisión Dictaminadora consistió en verificar los aspectos de legalidad, de homogeneidad en criterios normativos aplicables, en la confronta de tasas, cuotas y tarifas entre la propuesta para 2020 en relación a las del ejercicio inmediato anterior para determinar el crecimiento real de los ingresos, y demás particularidades que derivaron de la revisión de la iniciativa. -

Candidatos Que Integran Las Planillas De Ayuntamientos Y Listas De Regidores

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE PRERROGATIVAS Y ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL PARTIDO: Movimiento Ciudadano CANDIDATOS QUE INTEGRAN LAS PLANILLAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS Y LISTAS DE REGIDORES MUNICIPIO: AHUACUOTZINGO PARTIDO: Movimiento Ciudadano Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario FILIBERTO ABARCA TEPEC H 43 Presidente Municipal Suplente LADISLAO SANCHEZ ROMERO H 28 Sindico Procurador Propietario ESTEFANIA VENEGAS DIAZ M 58 Sindico Procurador Suplente SENORINA CASTILLO ATEMPA M 46 Regidor Propietario VICTOR MOCTEZUMA RENDON H 38 Regidor Suplente MARIANO MACEDONIO MORALES H 53 Regidor Propietario (2) VICTORIA ALCOCER CASARRUBIAS M 38 Regidor Suplente (2) CONCEPCION BELTRAN CASARRUBIAS M 29 MUNICIPIO: APAXTLA PARTIDO: Movimiento Ciudadano Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario DAVID MANJARREZ MIRANDA H 46 Presidente Municipal Suplente MATEO OCAMPO CUEVAS H 59 Sindico Procurador Propietario ESTHER BRITO BRITO M 53 Sindico Procurador Suplente HAYDE ALCANTARA MIRANDA M 33 Regidor Propietario J. GUADALUPE VILLARES CUEVAS H 63 Regidor Suplente MARIO ROMAN BRITO H 58 Regidor Propietario (2) AZALIA BETSABE ROMAN SALGADO M 24 Regidor Suplente (2) LETICIA BRITO ABARCA M 39 Regidor Propietario (3) FERNANDO SANTANA SANDOVAL H 38 Regidor Suplente (3) YILMAR VENOSA SOLIS H 31 Regidor Propietario (4) LESLY YOMALLY MONTUFAR SANCHEZ M 26 Regidor Suplente (4) HERLINDA MANJARREZ SOTO M 53 MUNICIPIO: -

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long Lat Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez 10 DE ABRIL 994427 164945 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez ACAPULCO 2000 994837 165217 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 995311 165142 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AGROPECUARIA 994720 165318 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AGUA DEL PERRO 993354 170544 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AGUA ZARCA DE LA PEÑA 993614 165805 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AGUAS CALIENTES 993826 165033 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez ALTO DEL CAMARÓN 993454 170305 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AMATEPEC 993029 165849 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AMATILLO 993958 164913 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AMPLIACIÓN FRONTERA 994857 165331 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez APALANI 993522 165113 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez APANHUAC (APANGUAQUE) 993520 165448 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez ARROYO EL EJIDO 994141 165915 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez ARROYO VERDE 994020 165548 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez BANCO DE ORO 994747 165317 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez BARRA VIEJA 993736 164129 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez BARRIO NUEVO DE LOS MUERTOS 993238 165334 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez BELLA VISTA PAPAGAYO 993602 164626 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CABEZA DE TIGRE 993505 165119 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CACAHUATE 994216 164326 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CACAHUATEPEC 993643 165311 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CAMPANARIO 993417 165006 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CAMPO ROJO 994834 170619 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CANDELILLA (LAS PALMITAS) 994221 164700 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CARABALÍ 995245 165352 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CERRO DE -

El Contenido De Este Archivo No Podrá Ser Alterado O

EL CONTENIDO DE ESTE ARCHIVO NO PODRÁ SER ALTERADO O MODIFICADO TOTAL O PARCIALMENTE, TODA VEZ QUE PUEDE CONSTITUIR EL DELITO DE FALSIFICACIÓN DE DOCUMENTOS DE CONFORMIDAD CON EL ARTÍCULO 244, FRACCIÓN III DEL CÓDIGO PENAL FEDERAL, QUE PUEDE DAR LUGAR A UNA SANCIÓN DE PENA PRIVATIVA DE LA LIBERTAD DE SEIS MESES A CINCO AÑOS Y DE CIENTO OCHENTA A TRESCIENTOS SESENTA DÍAS MULTA. DIRECION GENERAL DE IMPACTO Y RIESGO AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD REGIONAL, DEL PROYECTO: CAMINO TLACOTEPEC - ACATLÁN DEL RIO, TRAMO: DEL KM. 5+000 AL KM. 10+000, MUNICIPIO DE GRAL. HELIODORO CASTILLO, ESTADO DE GUERRERO. Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes Centro Guerrero (SCT). Dr. Gabriel Leyva Alarcón sin número Burócrata Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Guerrero C.P. 39090. Tel. 01 (747) 116-2742. Noviembre del 2019. ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL DEL CAMINO TLACOTEPEC - ACATLÁN DEL RIO, TRAMO: DEL KM. 5+000 AL KM. 10+000, MUNICIPIO DE GRAL. HELIODORO CASTILLO, ESTADO DE GUERRERO. Contenido I. DATOS GENERALES DEL PROYECTO, DEL PROMOVENTE Y DEL RESPONSABLE DEL ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL 3 I.1 Datos generales del proyecto 3 1.1.1. Nombre del proyecto 3 I.1.2 Ubicación del proyecto. 3 1.1.3 Duración del proyecto. 12 I.2 Datos generales del Promovente 13 I.2.1 Nombre o razón social 13 I.2.2 Registro Federal de Contribuyentes del promovente 13 I.2.3 Nombre y cargo del representante legal 13 I.2.4 Dirección del promovente o de su representante legal 13 I.2.5 Nombre del consultor que elaboró el estudio. 13 I.2.6 Nombre del responsable técnico de la elaboración del estudio 13 I.2.7 Registro Federal de Contribuyentes o CURP 13 I.2.8 Dirección del responsable técnico del estudio 13 II. -

La Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR)

Resultados de la convocatoria del Programa ProÁrbol de la Comisión Nacional Forestal 2012: La Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR) a través de la Gerencia Estatal Guerrero y el Gobierno del Estado de Guerrero, con fundamento en los artículos 11, 15 y 27 de las Reglas de Operación del Programa ProÁrbol 2012 de la Comisión Nacional Forestal, publicado en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el 21 de diciembre de 2011; da a conocer el resultado de las solicitudes ASIGNADAS para 2012, según acuerdo del Comité Técnico del Estado de Guerrero, en la sesión de fecha 22 de Marzo de 2012. Asimismo se da a conocer el calendario de capacitación sobre derechos y obligaciones de los beneficiarios de dicho programa: Solicitantes con recursos ASIGNADOS Superficie ó Unidad de Concepto de apoyo No. Folio Solicitud Solicitante Folio del apoyo Nombre del predio Municipio cantidad medida Monto asignado a/ asignada (especificar) B1.4 COSERVACIÓN 1 S201212001503 EJIDO IGUALITA Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000230 EL PALMAR XALPATLÁHUAC 60 HAS. $174,000.00 DE SUELOS BIENES COMUNALES DE SAN B1.4 COSERVACIÓN 2 S201212001563 MIGUEL CHIEPETLAN Y SUS Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000236 LOMA DE POCITO TLAPA DE COMONFORT 60 HAS. $174,000.00 ANEXOS DE SUELOS B1.4 COSERVACIÓN 3 S201212000933 EJIDO CUBA Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000132 EL RANCHO XALPATLÁHUAC 60 HAS. $174,000.00 DE SUELOS B1.4 COSERVACIÓN BIENES COMUNALES DE TONALAPA 4 S201212001389 Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000212 TLAPA DE COMONFORT 70 HAS. $203,000.00 ZACUALPAN TLALXOTALCO DE SUELOS B1.4 COSERVACIÓN 5 S201212001135 EJIDO CHIMALACACINGO Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000178 LA SIDRA COPALILLO 60 HAS. $174,000.00 DE SUELOS B1.4 COSERVACIÓN BIENES COMUNALES DE 6 S201212001769 Y RESTAURACIÓN BCS201212000269 ZAPOTE BLANCO TLAPA DE COMONFORT 80 HAS. -

Candidatos Que Integran Las Planillas De Ayuntamientos Y Listas De Regidores

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE PRERROGATIVAS Y ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL PARTIDO: Partido Verde Ecologista de México CANDIDATOS QUE INTEGRAN LAS PLANILLAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS Y LISTAS DE REGIDORES MUNICIPIO: ACATEPEC PARTIDO: Partido Verde Ecologista de Mexico Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario VIDAL NERI BASURTO H 38 Presidente Municipal Suplente MAURO HILARIO EULOGIA H 39 Sindico Procurador Propietario EPIFANIA GARCIA FLORES M 47 Sindico Procurador Suplente ROSENDA ALFONZO AURELIO M 27 Regidor Propietario ESTEBAN MARCELINO VAZQUEZ H 43 Regidor Suplente TIMOTEO ESPINOZA JULIO H 29 Regidor Propietario (2) NORMA MAURILO MORALES M 27 Regidor Suplente (2) EDUWIGIS HILARION BERNARDINO M 28 Regidor Propietario (3) MARTIN LORENZO MODESTA H 50 Regidor Suplente (3) FELIPE MENDEZ FERRER H 36 Regidor Propietario (4) ELVIRA BASILIO LIBRADO M 25 Regidor Suplente (4) GLAFIRA AURELIO CRUZ M 26 MUNICIPIO: AJUCHITLAN DEL PROGRESO PARTIDO: Partido Verde Ecologista de Mexico Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario EDGAR RAMIRO DIEGO SANTIAGO H 22 Presidente Municipal Suplente FULGENCIO VERGARA URBANO H 29 Sindico Procurador Propietario LADY PIZARRO MONDRAGON M 29 Sindico Procurador Suplente MERLI CRUZ LOPEZ M 22 Regidor Propietario ERIC PANTALEON ALVAREZ H 35 Regidor Suplente JOSE OLEGARIO CALDERON CERVANTES H 37 Regidor Propietario (2) SOLYANET LARA ANTUNEZ M 26 Regidor Suplente (2) -

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long Lat Distrito Federal Tlalpan RANCHO MEZONTEPEC 991400 191113 Guerrero Acatepec AGUA FRÍA 985115 171655 Guerrero Acatepec COLONIA OCOTE CAPULÍN 985052 172123 Guerrero Acatepec IXTLAHUATEPEC 985158 172009 Guerrero Acatepec LOMA TUZA 985209 172110 Guerrero Acatepec MESÓN ZAPATA 985147 172011 Guerrero Acatepec PLAN DE PALO VIEJO (LOMA VISTA) 985046 171636 Guerrero Acatepec RANCHO PORFIRIO DE LA CRUZ 984947 171548 Guerrero Atlixtac CHALMA 985234 172926 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez ACUENTLA 991456 173107 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez AHUEXOTITLÁN 991439 173145 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez COAQUIMIXCO 991408 173446 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez CONETZINGO 991557 173138 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez EL PERAL 991504 173416 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez EL PINORAL 991604 173213 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez POPOYATLAJCO 991610 173002 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez RANCHO COAQUIMIXCO 991434 173521 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez TENEXATLAJCO (TENEXATLACO) 991541 173320 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez TEPEHUIXCO 991505 173624 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez TEPEXAXOCOTITLÁN 985405 172915 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez TETITLÁN DE LA LIMA 991440 173721 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez TIERRA BLANCA OCOTITO 990011 172029 Guerrero Chilapa de Álvarez TLATEMPA 990255 173121 Guerrero Chilpancingo de los Bravo ACAHUIZOTLA 992803 172138 Guerrero Chilpancingo de los Bravo AMOJILECA 993409 173410 Guerrero Chilpancingo de los Bravo AMPLIACIÓN TRINCHERA 992825 173220 Guerrero Chilpancingo de los Bravo AZINYAHUALCO (CAÑADA DE AZINGEHUALCO) 993319 172422 Guerrero