CAUTION AHEAD Overdue Investments for New York’S Aging Infrastructure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Onondaga County District Attorney's Office Plan

New York State POLICE REFORM AND REINVENTION COLLABORATIVE ONONDAGA COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE PLAN WILLIAM J. FITZPATRICK DISTRICT ATTORNEY March 9, 2021 P a g e 1 | 61 Content Outline Executive Summary ……………………….........…..………………….………………………………………..3 Introduction to the Collaborative Process ………...………………………...………..………………………..4 Public Comments by InterFaith Works Community Forums Governor’s Executive Order 203 Accountability Goals POLICE STRUCTURE SUB-COMMITTEE ………….………………………………………..…….………9 Chief Kenton Buckner / Chief Joe Cecile, co-chair Use of Force Policy Body Worn Camera Policy No Knock Warrant Procedures POLICE/COMMUNITY RELATIONS SUB-COMMITTEE ………..……………………….……………10 Council President Helen Hudson, co-chair Citizen Review Board Procedural Justice o Right to Know Law Violence Interrupters: Reduction Intervention School Safety and Security Diversity Hiring CRIME ANALYSIS SUB-COMMITTEE ….………………………………………………..…………….…23 Sheriff Gene Conway / Chief Joe Ciciarelli, co-chair Problem Oriented Policing Hot Spots Focused Deterrence Environmental Design Role of Crime Analysis Center (CAC) TRAINING SUB-COMMITTEE ………………………………..……………..…………………..…………29 Chief Mike Crowell, co-chair Racial Bias: (Racial Justice in Policing) De-escalation: Focused deterrence o Implicit Bias Awareness Training Crisis Intervention: Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion Program ALTERNATIVES TO POLICE RESPONSE SUB-COMMITTEE …………………………………..……42 County Legislature Linda Ervin, co-chair Proper Response to Non-Criminal Calls Diversionary Programs and -

In the Service of Others: from Rose Hill to Lincoln Center

Fordham Law Review Volume 82 Issue 4 Article 1 2014 In the Service of Others: From Rose Hill to Lincoln Center Constantine N. Katsoris Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constantine N. Katsoris, In the Service of Others: From Rose Hill to Lincoln Center, 82 Fordham L. Rev. 1533 (2014). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol82/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEDICATION IN THE SERVICE OF OTHERS: FROM ROSE HILL TO LINCOLN CENTER Constantine N. Katsoris* At the start of the 2014 to 2015 academic year, Fordham University School of Law will begin classes at a brand new, state-of-the-art building located adjacent to the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. This new building will be the eighth location for Fordham Law School in New York City. From its start at Rose Hill in the Bronx, New York, to its various locations in downtown Manhattan, and finally, to its two locations at Lincoln Center, the law school’s education and values have remained constant: legal excellence through public service. This Article examines the law school’s rich history in public service through the lives and work of its storied deans, demonstrating how each has lived up to the law school’s motto In the service of others and concludes with a look into Fordham Law School’s future. -

Tremont • East Tremont • Morris Heights • Claremont • Concourse • Highbridge

University Heights TREMONT • EAST TREMONT • MORRIS HEIGHTS • CLAREMONT • CONCOURSE • HIGHBRIDGE Charlotte St, G12-H12 E Burnside Av, C5-C7 Fairmount Pl, D11-D12 Hughes Av, A10-D10 Montgomery Av, E3-G2 Shakespeare Av, G3-L4 W 166 St, L2-L3 W 183 St, A3-A5 Christ the King Church and Head Start, C4, D6, G12, K3, M9 Morgan Playground, K9 P.S.58, D8 Royal Hospital, Unity Park, K9 Streets Chisholm St, J12 E Mt Eden Av, G6-F8 Featherbed Ln, G4-F4 Intervale Av, K12-L12 Monroe Av, E7-G7 Sheridan Av, G6-M6 W 167 St, K2-L3 W Tremont Av, D2-D5 School, J6 Highbridge Houses, L2 Morris Heights P.O., C5 P.S. 64, H5 Sacred Heart Church and University Heights Bridge, A1-A2 Key Clay Av, E7 E 164 St, M12 Findlay Av, J7-M7 Inwood Av, G4 Morris Av, A6-M7 W 168 St, K2-K3 Woodycrest Av, K3-M1 Claremont Park, G6-J7 Highbridge P.O, J4 Morris High School, L10 P.S. 61, G12 School, K3 University Heights Hospital, accessible Transit Police Sherman Av, K6-M6 entrance & exit District Office Adams Pl, A10 Claremont Pkwy, G8 E 166 St, M4-L12 Fletcher Pl, A9 Ittner Pl, E8 Morton Pl, E3 W 169 St, K2-K4 Wythe Pl, H5-J5 Cleopatra Playground, E7 Highbridge Public Library, K3 P.S. 70, F6 Shield Institute, E3 University Heights P.O, G3 Stebbins Av, H12 Morrisania Church (Presby.), K5 District 1 TPD Alden Pl, C8 University Woods, B2-C2 P.S. 73, M3 St Augustine's Church, L10 Clark Place E, J5 E 167 St, K4-L12 Folin St, B7-A8 Jackson Av, L10 Mt Eden Pkwy, G6-G7 Suburban Pl, G12 W 170 St, J2-J4 Concourse Nursing Home, M5 Highbridge Senior Center, L3 Morrisania Family Care D R Andrews Av N, A4-B4 T W.H. -

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

Bam 2016 Annual Report

BAM 2016 2 1ANNUAL REPORT 0 6 BAM’s mission is to be the home for adventurous artists, audiences, and ideas. 3—6 Community, 31–33 GREETINGS DanceMotion USASM, 34–35 Chair Letter, 4 Visual Art, 36–37 President & Executive Producer’s Letter, 5 Membership, 38 BAM Campus, 6 Membership, 37—39 7—35 40—47 WHAT WE DO WHO WE ARE 2015 Next Wave Festival, 8–10 BAM Board, 41 2016 Winter/Spring Season, 11–13 BAM Supporters, 42–45 Also On Stage, 14 BAM Staff, 46–47 BAM Rose Cinemas, 15–20 48—50 First-run Films, 16 NUMBERS BAMcinématek, 17–18 BAM Financial Statements, 49–50 BAMcinemaFest, 19 HD Screenings, 20 51—55 BAMcafé Live, 21–22 THE TRUST BAM Hamm Archives, 23 BET Chair Letter, 52 Digital Media, 24 BET Donors, 53 Education & Humanities, 25–30 BET Financial Statements, 54–55 2 TKTKTKTK Cover: Urban Bush Women in Walking with ‘Trane| Photo: Julieta Cervantes Greetings GREETINGS 3 TKTKTKTK 2016 Winter/Spring | Royal Shakespeare Company in Henry IV Part I | Photo: Richard Termine Change is anticipated, expected, welcomed. — Alan H. Fishman Dear Friends, As you all know, and perhaps celebrated (!), Anne Bogart, Ivo van Hove, Long time trustee Beth Rudin Dewoody As I end my leadership role, I want to I stepped down as chairman of this William Kentridge, and many others. became an honorary trustee. Mark Jackson express my thanks to all I have met and miraculous institution effective December and Danny Simmons, both great trustees, worked with along the way. Together we have 31, 2016. -

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(Es)

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(es) Location Remains UN Plaza Hotel (Park Hyatt) 1981 1 UN Plaza Manhattan N Reader's Digest 1981 28 West 23rd Street Manhattan Y NYC Dept of General Services 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Summit Hotel 1981 51 & LEX Manhattan N Schieffelin and Company 1981 2 Park Avenue Manhattan Y Ernst and Company 1981 1 Battery Park Plaza Manhattan Y Reeves Brothers, Inc. 1981 104 W 40th Street Manhattan Y Alpine Hotel 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Brooks Brothers 1982 1120 Ave of Amer. Manhattan Y Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Sanwa Bank 1982 220 Park Avenue Manhattan Y City Miday Club 1982 140 Broadway Manhattan Y Royal Business Machines 1982 Manhattan Manhattan * Billboard Publications 1982 1515 Broadway Manhattan Y U.N. Development Program 1982 1 United Nations Plaza Manhattan N Population Council 1982 1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza Manhattan Y Park Lane Hotel 1983 36 Central Park South Manhattan Y U.S. Trust Company 1983 770 Broadway Manhattan Y Ford Foundation 1983 320 43rd Street Manhattan Y The Shoreham 1983 33 W 52nd Street Manhattan Y MacMillen & Co 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Solomon R Gugenheim 1983 1071 5th Avenue Manhattan * Museum American Bell (ATTIS) 1983 1 Penn Plaza, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y NYC Office of Prosecution 1983 80 Center Street, 6th Floor Manhattan Y Mc Hugh, Leonard & O'Connor 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Keene Corporation 1983 757 3rd Avenue Manhattan Y Melhado, Flynn & Assocs. 1983 530 5th Avenue Manhattan Y Argentine Consulate 1983 12 W 56th Street Manhattan Y Carol Management 1983 122 E42nd St Manhattan Y Chemical Bank 1983 277 Park Avenue, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y Merrill Lynch 1983 55 Water Street, Floors 36 & 37 Manhattan Y WNET Channel 13 1983 356 W 58th Street Manhattan Y Hotel President (Best Western) 1983 234 W 48th Street Manhattan Y First Boston Corp 1983 5 World Trade Center Manhattan Y Ruffa & Hanover, P.C. -

Senior Issue 2020

2019 - 2020 The Miegian Vol. 63, Iss. 5 | Bishop Miege High School | 5041 Reinhardt Dr, Roeland Park, KS | July 17, 2020 2 CONTENTS 02 Senior Issue Introduction 04 The Miegian’s COVID-19 Response 06 Collage 08 Seniors and their Bright Futures 12 Collage 14 Featured Seniors 16 Senior Survey 18 Featured Writings 19 Senior Sports 24 Senior Advice & Teacher Memories 26 Farewell Miege 2019-2020 Miegian Staff Maren O’Connell Moira Sutherlin Luke Lazarczyk Editor-in-Chief Senior Issue Co-Editor Sports Editor Maddy McBride Kaitlin Thrun Isabel Copeland Staff Writer Staff Writer Staff Writer Sindy Garcia Allison Masilionis Cooper Brandmeyer Staff Writer Staff Designer Staff Photographer 3 Letter from the Editor Maren O’Connell eye-catching and a colorful keepsake granted the beauty of CTRL+Z (undo for each student if they so desire. keys). (Of course technology is often Editor-in-Chief The first step was transitioning unreliable—ahem—sometimes re- from a traditional newspaper to a sulting in an entire deletion of the f you know me, you probably are magazine-type format through the newspaper’s servers. Don’t worry, we aware that I tend to downplay my help of our printing company, Best recovered from this setback.) Iachievements and shrug them off Graphics. Mrs. McCambridge said After receiving a note from Ms. as not being that important. It was she shared that her editor loves the Hartwig at the end of my sophomore no exception when I learned that I smell of the pages, after I walked year, enticing me to join the news- was going to be Editor in Chief for into class raving about the scent. -

2017 Annual Report Reaching Out, Making Connections, and Following Through with Treatment and Housing Services That Change Lives Is Demanding Work

2017 Annual Report Reaching out, making connections, and following through with treatment and housing services that change lives is demanding work. The men and women who work in Odyssey House’s community-based programs understand what is at stake when substance misuse or mental health problems are not treated. While they see the pain of addiction and the tragedy of lives cut short, they also see hope in recovery and lives saved. Helping New Yorkers overcome life challenges keeps us going and keeps us on the front lines. In this report, read about how volunteer recovery coach Jesse Westbrook and his colleagues at the Odyssey House Recovery Center are reaching out and connecting with families, adolescents, and seniors in their South Bronx community. Building community and saving lives IT IS THE MISSION OF ODYSSEY HOUSE: To provide comprehensive and innovative services to the broadest range of metro New York’s population who: • Abuse drugs • Abuse alcohol • Suffer from mental illness To provide high quality, holistic treatment impacting all major life spheres: psychological, physical, social, family, educational and spiritual. To support personal rehabilitation, renewal and family restoration. In all of its activities, Odyssey House undertakes to act as a responsible employer and member of the community, and manage the assets of the organization in a professional manner. 1 WHAT YOU CANNOT DO ALONE, WE CAN DO TOGETHER Treatment and recovery services are at the heart of treatment programs. However, treatment is of what we provide at Odyssey House. Supporting just the beginning of what it takes to save a New Yorkers and their families as they overcome life. -

Friday, Dec. 14Th 7:30 to 9:00Am Celebration in Late October with Our An- You, Delton, for Your Service

NE Community Leader Spotlight - Mayor Laura Wheat 2 Tarrant County Domestic Relations Office 2 NE Transportation Summit- Save the Date! 3 NW Metroport Chamber of Commerce 4 United Way Fundraiser Follow-up 4 An Historic Moment In Time - Birdville Historical Society 5 Tarrant County Heroes Recognized 5 1895 Courthouse Bell Tower Rededication 5 Holiday Photo Contest Winner Announced 5 Mid-Cities Care Corps 6 Holy Trinity Catholic School 6 Haslet Public Library 7 Honoring our Veterans 7 Transportation Updates on Northeast Tarrant County Road Projects 8 Calendar of Events 9 Contact Information 9 Christmas is here along with some County. He will be enjoying time at his cold weather, and it is time to cele- home in the country and not having to drive brate. The Precinct 3 staff started the one hour or more one way to work. Thank Friday, Dec. 14th 7:30 to 9:00am celebration in late October with our an- you, Delton, for your service. Enjoy the nual United Way Fundraising BBQ time…you will be missed. Please join me for coffee and donut s! Luncheon. We served over 200 people – Happenings in Tarrant County in the barbecue brisket and sausage, potato last few months: salad, beans, bread, desserts, ice tea or water - while raising funds for United The 1895 Courthouse Clock Tower Way of Tarrant County. (see page 4) Rededication in late October (see photo page 5). Northeast Sub-Courthouse Our staff Christmas photo is at our Precinct 3 will be moving into a new 645 Grapevine Hwy., Hurst TX 76054 Maintenance Center on Precinct Line Courthouse in late 2014 or early 2015. -

Skyscrapers and District Heating, an Inter-Related History 1876-1933

Skyscrapers and District Heating, an inter-related History 1876-1933. Introduction: The aim of this article is to examine the relationship between a new urban and architectural form, the skyscraper, and an equally new urban infrastructure, district heating, both of witch were born in the north-east United States during the late nineteenth century and then developed in tandem through the 1920s and 1930s. These developments will then be compared with those in Europe, where the context was comparatively conservative as regards such innovations, which virtually never occurred together there. I will argue that, the finest example in Europe of skyscrapers and district heating planned together, at Villeurbanne near Lyons, is shown to be the direct consequence of American influence. Whilst central heating had appeared in the United Kingdom in the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries, district heating, which developed the same concept at an urban scale, was realized in Lockport (on the Erie Canal, in New York State) in the 1880s. In United States were born the two important scientists in the fields of heating and energy, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) and Benjamin Thompson Rumford (1753-1814). Standard radiators and boilers - heating surfaces which could be connected to central or district heating - were also first patented in the United States in the late 1850s.1 A district heating system produces energy in a boiler plant - steam or high-pressure hot water - with pumps delivering the heated fluid to distant buildings, sometimes a few kilometers away. Heat is therefore used just as in other urban networks, such as those for gas and electricity. -

Comparative Screening Results Report

Metro-North Penn Station Access Major Investment Study/Draft Environmental Impact Statement COMPARATIVE SCREENING RESULTS REPORT Prepared for Metro-North Railroad Prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. September 2002 Comparative Screening Results Report TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................ 1 A. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................... 3 1. STUDY OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................. 3 2. PURPOSE AND ORGANIZATION OF DOCUMENT ......................................................................... 4 B. SCREENING PROCESS............................................................................................................ 5 1. OVERVIEW............................................................................................................................. 5 2. SCREENING METHODOLOGY AND CRITERIA ............................................................................ 5 C. INTERMEDIATE ALTERNATIVES...................................................................................... 11 1. SERVICE PLANS.................................................................................................................... 11 2. INFRASTRUCTURE REQUIREMENTS....................................................................................... -

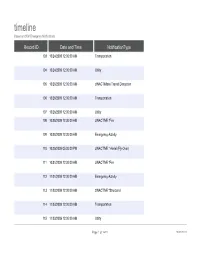

Timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications

timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications Record ID Date and Time NotificationType 103 10/24/2009 12:00:00 AM Transportation 104 10/24/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility 105 10/26/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIMass Transit Disruption 106 10/26/2009 12:00:00 AM Transportation 107 10/26/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility 108 10/28/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Fire 109 10/28/2009 12:00:00 AM Emergency Activity 110 10/29/2009 05:00:00 PM zINACTIVE * Aerial (Fly-Over) 111 10/31/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Fire 112 11/01/2009 12:00:00 AM Emergency Activity 113 11/02/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Structural 114 11/03/2009 12:00:00 AM Transportation 115 11/03/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility Page 1 of 1419 10/02/2021 timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications Notification Title [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] Major Gas Explosion 32-25 Leavitt St. [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] Page 2 of 1419 10/02/2021 timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications Email Body Notification 1 issued on 10/24/09 at 11:15 AM. Emergency personnel are on the scene of a motor vehicle accident involving FDNY apparatus on Ashford Street and Hegeman Avenue in Brooklyn. Ashford St is closed between New Lots Ave and Linden Blvd. Hegeman Ave is closed from Warwick St to Cleveland St. Notification 1 issued 10/24/2009 at 6:30 AM. Emergency personnel are on scene at a water main break in the Fresh Meadows section of Queens.