Towards the Renewal of Anglican Identity As Communion: the Relationship of the Trinity,Missio Dei, and Anglican Comprehensiveness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Alec Vidler on Christian Faith and Secular Despair Born in Rye

Alec Vidler On Christian Faith and Secular Despair Born in Rye, Sussex, son of a shipping businessman, Alec Vidler ( 1899‐1991)was educated at Sutton Valence School, Kent, read theology at Selwyn College, Cambridge (B.A. 1921),then trained for the Anglican ministry at Wells Theological College. He disliked Wells and transferred to the Oratory of the Good Shepherd, Cambridge, an Anglo‐Catholic community of celibates, and was ordained priest in 1923. He retained a life‐time affection for the celibate monkish life, never marrying but having a wide range of friends, including Malcolm Muggeridge, who was at Selwyn with him. Muggeridge’s father was a prominent Labourite and Vidler imbibed leftist sympathies in that circle. His first curacy was in Newcastle, working in the slums. He soon came to love his work with working class parishioners and was reluctantly transferred to St Aidan’s Birmingham, where he became involved in a celebrated stoush with the bishop E. W. Barnes, himself a controversialist of note. Vidler’s Anglo‐ Catholic approach to ritual clashed with Barnes’s evangelicalism. Vidler began a prolific career of publication in the 1920s and 30s. In 1931 he joined friends like Wilfred Ward at the Oratory House in Cambridge, steeping himself in religious history and theology, including that of Reinhold Niebuhr and “liberal Catholicism”. In 1939 Vidler became warden of St Deiniol’s Library, Hawarden (founded by a legacy from Gladstone) and also editor of the leading Anglican journal Theology, which he ran until 1964, exerting considerable progressive influence across those years. He also facilitated a number of religious think‐tanks in these, and later, years. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

Book Reviews the DOCTRINE of GRACE in the APOSTOLIC FATHERS

Book Reviews THE DOCTRINE OF GRACE IN THE APOSTOLIC FATHERS. By T. F. Torrance. 15opp. Oliver <8- Boyd. 12/6. Probably all students of theology must have noticed the significant change in the understanding of the term ' grace ' from the time of the New Testament onwards. Perhaps, too, they will have wondered how and why it was that the evangelical Apostolic message degenerated so completely into the pseudo-Christianity of the Dark and Middle Ages. It is the aim of Dr. Torrance in his small but important dis sertation to supply an answer to both these problems. He does so by taking the word ' grace ' and comparing the Biblical usage with that of the accepted Fathers of the sub-Apostolic period : the Didache, I and II Clement, Ignatius, Polycarp, Barnabas, and the Shepherd of Hermas. The resultant study has a threefold value for the theologian. It has, first, a narrower linguistic and historical value as a contribution to the understanding of the conception of grace in the first hundred years or so of Christian theology. As the author himself makes clear in the useful Introduction, this question is not so simple as some readers might suppose, for the term grace had many meanings in Classical and Hellenistic Greek. It is important then to fix the exact con notation in the New Testament itself, and also to achieve an aware ness of any shift of understanding in the immediate post-Apostolic period. The exegetical discussions at the end of each chapter have a considerable value in the accomplishment of this task. -

Full Text Available (PDF)

JOURNAL of the EDINBURGH BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY edinburgh bibliographical society http://www.edinburghbibliographicalsociety.org.uk/ Scottish Charity Number SC014000 President ian mcgowan Vice-Presidents peter garside heather holmes Secretary Treasurer helen vincent robert betteridge Rare Book Collections Rare Book Collections National Library of Scotland National Library of Scotland George IV Bridge George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Edinburgh EH1 1EW [email protected] [email protected] Committee david finkelstein, warren mcdougall, joseph marshall, carmen wright, william zachs Editors david finkelstein, peter garside, warren mcdougall, joseph marshall, carmen wright, william zachs Review Editor heather holmes the annual subscription, payable in sterling, is £20 for institutional members and £15 for individual members (£10 for students). Members receive a copy of the annual Journal and of Occasional Publications. contributions for the Journal should be submitted for consideration to the Editors in electronic form, in accordance with the MHRA Style Guide. Articles, particularly as they relate to Scottish interests, are invited in the fields of bibliography, the book trade, the history of scholarship and libraries, and book collecting. Submissions are refereed. the editors also welcome suggestions for the Occasional Publications. the society meets regularly during the academic year, and has an annual visit in May. Details are on the website. © The Edinburgh Bibliographical Society All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publishers, or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the United Kingdom by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS Typeset by Kamillea Aghtan and printed by 4edge Limited. -

One Baptism, One Hope in God's Call

A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDING OFFICERS OF THE GENERAL CONVENTION Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ: As your Presiding Officers we appointed the Special Commission on the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion late in 2005. The Special Commission was asked to prepare the way for a consideration by the 75th General Convention of recent developments in the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion with a view to maintaining the highest degree of communion possible. They have admirably discharged this very weighty task. With our deep thanks to them we commend their report to you. Here we would like to make three observations. First, though this document is a beginning point for legislative decisions—and indeed includes eleven resolutions—it is first and foremost a theological document. Its primary focus is on our understanding of our participation as members of the Anglican Communion in God’s Trinitarian life and God’s mission to which we are called. Second, the report is intended as the beginning point for a conversation that will take place in Columbus under the aegis of the Holy Spirit. That is, it is intended to start the conversation and not conclude it: the Commission has seen itself as preparing the General Convention to respond in the wisest possible ways. Again, we thank the members of the Special Commission who have been servants of this process of discernment. Third, following up on the careful work done by the Commission, the General Convention is now invited into the Windsor Process and the further unfolding of our common life together in the Anglican Communion. -

Christian Public Ethics Sagepub.Co.Uk/Journalspermissions.Nav Tjx.Sagepub.Com Robin Gill

Theology 0(0) 1–9 ! The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: Christian public ethics sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav tjx.sagepub.com Robin Gill This special online issue of Theology focuses upon Christian public ethics or, more specifically, upon those forms of Christian ethics that have contributed sig- nificantly to public debate. Throughout the 95 years of the journal’s history, there has been discussion about public ethics (even if it has not always been named as such). However, Christian public ethics had a particular flourishing between 1965 and 1975, when Professor Gordon Dunstan (1918–2004) was editor. When I became editor of Theology in January 2014, I acknowledged at once my personal debt to Gordon. He encouraged and published my very first article when I was still a postgraduate in 1967, and several more articles beyond that. And, speaking personally, his example of deep engagement in medical ethics was inspirational. When he died, The Telegraph noted the following among his many achievements: He was president of the Tavistock Institute of Medical Psychology and vice-president of the London Medical Group and of the Institute of Medical Ethics. During the 1960s he was a member of a Department of Health Advisory Group on Transplant Policy, and from 1989 to 1993 he served on a Department of Health committee on the Ethics of Gene Therapy. From 1990 onwards he was a member of the Unrelated Live Transplant Regulatory Authority and from 1989 to 1993 he served on the Nuffield Council on Bioethics. (19 January 2004) The two most substantial ethical contributions that I have discovered in searching through back issues of Theology were both published when he was editor and were doubtless directly encouraged by him. -

Completed Thesis

THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Human Uniqueness: Twenty-First Century Perspectives from Theology, Science and Archaeology Josephine Kiddle Bsc (Biology) MA (Religion) Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2013 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester. The word count is: 89350 THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER ABSTRACT FOR THESIS Human Uniqueness: Twenty-First Century Perspectives from Theology, Science and Archaeology A project aiming to establish, through the three disciplines, the value of human uniqueness as an integrating factor for science with theology Josephine Kiddle Bsc (Biology) MA (Religion) Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Doctor of Philosophy February 2013 The theme that underlies the thesis is the challenge presented by science, as it developed from the time of the Enlightenment through the centuries until the present day, to Christian theology. The consequent conflict of ideas is traced in respect of biological science and the traditions of Protestant Christian doctrine, together with the advances of the developing discipline of prehistoric archaeology since the early nineteenth century. The common ground from which disagreement stemmed was the existence of human beings and the uniqueness of the human species as a group amongst all other creatures. With the conflict arising from this challenge, centring on the origin and history of human uniqueness, a rift became established between the disciplines which widened as they progressed through to the twentieth century. It is this separation that the thesis takes up and endeavours to analyse in the light of the influence of advancing science on the blending of philosophical scientific ideas with the elements of Christian faith of former centuries. -

The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism Amanda Oh Southern Methodist University, [email protected]

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Central University Libraries Award Documents 2019 The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism Amanda Oh Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/weil_ura Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Oh, Amanda, "The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism" (2019). The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Award Documents. 10. https://scholar.smu.edu/weil_ura/10 This document is brought to you for free and open access by the Central University Libraries at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Award Documents by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism Amanda Oh Professor Wellman HIST 4300: Junior Seminar 30 April 2018 Part I: Introduction The end of the seventeenth century in England saw the flowering of liberal ideals that turned on new beliefs about the individual, government, and religion. At that time the relationship between these cornerstones of society fundamentally shifted. The result was the preeminence of the individual over government and religion, whereas most of Western history since antiquity had seen the manipulation of the individual by the latter two institutions. Liberalism built on the idea that both religion and government were tied to the individual. Respect for the individual entailed respect for religious diversity and governing authority came from the assent of the individual. -

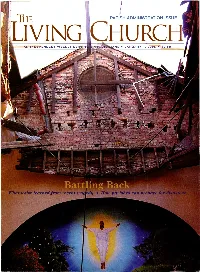

PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1Llving CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I

1 , THE PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1llVING CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I, ENDURE ... EXPLORE YOUR BEST ACTIVE LIVING OPTIONS AT WESTMINSTER COMMUNITIES OF FLORIDA! 0 iscover active retirement living at its finest. Cf oMEAND STAY Share a healthy lifestyle with wonderful neighbors on THREE DAYS AND TWO any of our ten distinctive sun-splashed campuses - NIGHTS ON US!* each with a strong faith-based heritage. Experience urban excitement, ATTENTION:Episcopalian ministers, missionaries, waterfront elegance, or wooded Christian educators, their spouses or surviving spouses! serenity at a Westminster You may be eligible for significant entrance fee community - and let us assistance through the Honorable Service Grant impress you with our signature Program of our Westminster Retirement Communities LegendaryService TM. Foundation. Call program coordinator, Donna Smaage, today at (800) 948-1881 for details. *Transportation not included. Westminster Communities of Florida www.WestminsterRetirement.com Comefor the Lifestyle.Stay for a Lifetime.T M 80 West Lucerne Circle • Orlando, FL 32801 • 800.948.1881 The objective of THELIVI N G CHURCH magazine is to build up the body of Christ, by describing how God is moving in his Church ; by reporting news of the Church in an unbiased manner; and by presenting diverse points of view. THIS WEEK Features 16 2005 in Review: The Church Begins to Take New Shape 20 Resilient People Coas1:alChurches in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina BYHEATHER F NEWfON 22 Prepare for the Unexpected Parish sUIVivalcan hinge on proper planning BYHOWARD IDNTERTHUER Opinion 24 Editor's Column Variety and Vitality 25 Editorials The Holy Name 26 Reader's Viewpoint Honor the Body BYJONATHAN B . -

A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO PUBLIC CATHOLICISM AND RELIGIOUS PLURALISM IN AMERICA: THE ADAPTATION OF A RELIGIOUS CULTURE TO THE CIRCUMSTANCE OF DIVERSITY, AND ITS IMPLICATIONS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Michael J. Agliardo, SJ Committee in charge: Professor Richard Madsen, Chair Professor John H. Evans Professor David Pellow Professor Joel Robbins Professor Gershon Shafir 2008 Copyright Michael J. Agliardo, SJ, 2008 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Michael Joseph Agliardo is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ......................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents......................................................................................................................iv List Abbreviations and Acronyms ............................................................................................vi List of Graphs ......................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................. viii Vita.............................................................................................................................................x -

Diocese in Europe Prayer Diary, July to December 2011

DIOCESE IN EUROPE PRAYER DIARY, JULY TO DECEMBER 2011 This calendar has been compiled to help us to pray together for one another and for our common concerns. Each chaplaincy, with the communities it serves, is remembered in prayer once a year, according to the following pattern: Eastern Archdeaconry - January, February Archdeaconry of France - March, April Archdeaconry of Gibraltar - May, June Diocesan Staff - July Italy & Malta Archdeaconry - July Archdeaconry of North West Europe - August, September Archdeaconry of Germany and Northern Europe Nordic and Baltic Deanery - September, October Germany - November Swiss Archdeaconry - November, December Each Archdeaconry, with its Archdeacon, is remembered on a Sunday. On the other Sundays, we pray for subjects which affect all of us (e.g. reconciliation, on Remembrance Sunday), or which have local applications for most of us (e.g. the local cathedral or cathedrals). Some chaplains might like to include prayers for the other chaplaincies in their deanery. We also include the Anglican Cycle of Prayer (daily, www.aco.org), the World Council of Churches prayer cycle (weekly, www.oikoumene.org, prayer resources on site), the Porvoo Cycle (weekly, www.porvoochurches.org), and festivals and commemorations from the Common Worship Lectionary (www.churchofengland.org/prayer-worship/worship/texts.aspx). Sundays and Festivals, printed in bold type, have special readings in the Common Worship Lectionary. Lesser Festivals, printed in normal type, have collects in the Common Worship Lectionary. Commemorations, printed in italics, may have collects in Exciting Holiness, and additional, non- biblical, readings for all of these may be found in Celebrating the Saints (both SCM-Canterbury Press). -

Missional Imperatives Archbishop Gomez

Missional Imperatives for the Anglican Church in the Caribbean The Most Rev. Drexel Gomez, Retired Archbishop of the West Indies Introduction The Church in The Province Of The West Indies (CPWI) is a member church of the Anglican Communion (AC). The AC is comprised of thirty-eight (38) member churches throughout the global community, and constitutes the third largest grouping of Christians in the world, after the Roman Catholic Communion, and the Orthodox Churches. The AC membership is ordinarily defined by churches being in full communion with the See of Canterbury, and which recognize the Archbishop of Canterbury as Primus Inter Pares (Chief Among Equals) amongst the Primates of the member churches. The commitment to the legacy of Apostolic Tradition, Succession, and Progression serves to undergird not only the characteristics of Anglicanism itself, provides the ongoing allegiance to some Missional Imperatives, driven and sustained by God’s enlivening Spirit. Anglican Characteristics Anglicanism has always been characterized by three strands of Christian emphases – Catholic, Reformed, and Evangelical. Within recent times, the AC has attempted to adopt specific methods of accentuating its Evangelical character for example by designating a Decade of Evangelism. More recently, the AC has sought to provide for itself a new matrix for integrating its culture of worship, work, and witness in keeping with its Gospel proclamation and teaching. The AC more recently determined that there should also be a clear delineation of some Marks of Mission. It agreed eventually on what it has termed the Five Marks of Mission. They are: (1) To proclaim the Good News of the Kingdom; (2) To teach, baptize and nurture new believers; (3) To respond to human need by loving service; (4) To seek to transform unjust structures in society to challenge violence of every kind and to pursue peace and reconciliation; (5) To strive to safeguard the integrity of creation, and sustain and renew the life of the earth.