Received 2280

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burke Building 400 North 34Th Street | Seattle, WA

THE Burke Building 400 North 34th Street | Seattle, WA NEIGHBORING TENANTS FOR LEASE LOCATION high-tech 6,185 sf Fremont companies include Adobe, Impinj, Suite 200 Seattle’s funky, creative neighborhood Google, and Tableau Software “Center of the Universe” LOCATED IN FREMONT, AN OASIS FOR TECH COMPANIES For leasing information, contact JEFF LOFTUS • Newly remodeled lobbies and restrooms • Professional Management with 206.248.7326 with showers on-site building engineers [email protected] • High Speed Internet (Comcast Cable, • Views of the Ship Canal Century Link, Accel Wireless) KEN HIRATA • Parking ratio of 2/1,000 206.296.9625 • Near Fremont Canal Park, Burke • Available now [email protected] Gilman Trail, unique local shops and distinctive eateries • $32.00 PSF, FS kiddermathews.com This information supplied herein is from sources we deem reliable. It is provided without any representation, warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied as to its accuracy. Prospective Buyer or Tenant should conduct an independent investigation and verification of all matters deemed to be material, including, but not limited to, statements of income and expenses. Consult your attorney, accountant, or other professional advisor. BurkeTHE Building PROXIMITY SEATTLE CBD 3 miles 10 minutes to AURORA BRIDGE downtown Seattle LAKE UNION FREMONT BRIDGE LAKE WASHINGTON SHIP CANAL N 34TH ST N 35TH ST THE BURKE BUILDING N 36TH ST JEFF LOFTUS KEN HIRATA kiddermathews.com 206.248.7326 | [email protected] 206.296.9625 | [email protected] 400 North 34th Street | Seattle, WA SHIP CANAL PARKING 2/1,000 spaces per 1,000 sf rentable area N 34TH ST SUITE 200 N 35TH ST BurkeTHE Building SECOND FLOOR SUITE 200 AVAILABLE NOW 6,185 sf JEFF LOFTUS | 206.248.7326 | [email protected] KEN HIRATA | 206.296.9625 | [email protected] This information supplied herein is from sources we deem reliable. -

Earnest 1 the Current State of Economic Development in South

Earnest 1 The Current State of Economic Development in South Los Angeles: A Post-Redevelopment Snapshot of the City’s 9th District Gregory Earnest Senior Comprehensive Project, Urban Environmental Policy Professor Matsuoka and Shamasunder March 21, 2014 Earnest 2 Table of Contents Abstract:…………………………………………………………………………………..4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….5 Literature Review What is Economic Development …………………………………………………………5 Urban Renewal: Housing Act of 1949 Area Redevelopment Act of 1961 Community Economic Development…………………………………………...…………12 Dudley Street Initiative Gaps in Literature………………………………………………………………………….14 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………15 The 9th Council District of Los Angeles…………………………………………………..17 Demographics……………………………………………………………………..17 Geography……………………………………………………………………….…..19 9th District Politics and Redistricting…………………………………………………23 California’s Community Development Agency……………………………………………24 Tax Increment Financing……………………………………………………………. 27 ABX1 26: The End of Redevelopment Agencies……………………………………..29 The Community Redevelopment Agency in South Los Angeles……………………………32 Political Leadership……………………………………………………………34 Case Study: Goodyear Industrial Tract Redevelopment…………………………………36 Case Study: The Juanita Tate Marketplace in South LA………………………………39 Case Study: Dunbar Hotel………………………………………………………………46 Challenges to Development……………………………………………………………56 Loss of Community Redevelopment Agencies………………………………..56 Negative Perception of South Los Angeles……………………………………57 Earnest 3 Misdirected Investments -

Seattle: Queen City of the Pacific Orn Thwest Anonymous

University of Mississippi eGrove Haskins and Sells Publications Deloitte Collection 1978 Seattle: Queen city of the Pacific orN thwest Anonymous James H. Karales Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/dl_hs Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation DH&S Reports, Vol. 15, (1978 autumn), p. 01-11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Deloitte Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Haskins and Sells Publications by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^TCAN INSTITUTE OF JC ACCOUNTANTS Queen City Seattle of the Pacific Northwest / eattle, Queen City of the Pacific Located about as far north as the upper peratures are moderated by cool air sweep S Northwest and seat of King County, corner of Maine, Seattle enjoys a moderate ing in from the Gulf of Alaska. has been termed by Harper's and other climate thanks to warming Pacific currents magazines as America's most livable city. running offshore to the west. The normal Few who reside there would disagree. To a maximum temperature in July is 75° Discussing special exhibit which they just visitor, much of the fascination of Seattle Fahrenheit, the normal minimum tempera visited at the Pacific Science Center devoted lies in the bewildering diversity of things to ture in January is 36°. Although the east to the Northwest Coast Indians are (I. to r.) do and to see, in the strong cultural and na ward drift of weather from the Pacific gives DH&S tax accountants Liz Hedlund and tional influences that range from Scandina the city a mild but moist climate, snowfall Shelley Ate and Lisa Dixon, of office vian to Oriental to American Indian, in the averages only about 8.5 inches a year, administration. -

The Dunbar Hotel and the Golden Age of L.A.’S ‘Little Harlem’

SOURCE C Meares, Hadley (2015). When Central Avenue Swung: The Dunbar Hotel and the Golden Age of L.A.’s ‘Little Harlem’. Dr. John Somerville was raised in Jamaica. DEFINITIONS When he arrived in California in 1902, he was internal: people, actions, and shocked by the lack of accommodations for institutions from or established by people of color on the West Coast. Black community members travelers usually stayed with friends or relatives. Regardless of income, unlucky travelers usually external: people, actions, and had to room in "colored boarding houses" that institutions not from or established by were often dirty and unsafe. "In those places, community members we didn't compare niceness. We compared badness," Somerville's colleague, Dr. H. Claude Hudson remembered. "The bedbugs ate you up." Undeterred by the segregation and racism that surrounded him, Somerville was the first black man to graduate from the USC dental school. In 1912, he married Vada Watson, the first black woman to graduate from USC's dental school. By 1928, the Somervilles were a power couple — successful dentists, developers, tireless advocates for black Angelenos, and the founders of the L.A. chapter of the NAACP. As the Great Migration brought more black people to L.A., the city cordoned them off into the neighborhood surrounding Central Avenue. Despite boasting a large population of middle and upper class black families, there were still no first class hotels in Los Angeles that would accept blacks. In 1928, the Somervilles and other civic leaders sought to change all that. Somerville "entered a quarter million dollar indebtedness" and bought a corner lot at 42nd and Central. -

The Artists' View of Seattle

WHERE DOES SEATTLE’S CREATIVE COMMUNITY GO FOR INSPIRATION? Allow us to introduce some of our city’s resident artists, who share with you, in their own words, some of their favorite places and why they choose to make Seattle their home. Known as one of the nation’s cultural centers, Seattle has more arts-related businesses and organizations per capita than any other metropolitan area in the United States, according to a recent study by Americans for the Arts. Our city pulses with the creative energies of thousands of artists who call this their home. In this guide, twenty-four painters, sculptors, writers, poets, dancers, photographers, glass artists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and more tell you about their favorite places and experiences. James Turrell’s Light Reign, Henry Art Gallery ©Lara Swimmer 2 3 BYRON AU YONG Composer WOULD YOU SHARE SOME SPECIAL CHILDHOOD MEMORIES ABOUT WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO SEATTLE? GROWING UP IN SEATTLE? I moved into my particular building because it’s across the street from Uptown I performed in musical theater as a kid at a venue in the Seattle Center. I was Espresso. One of the real draws of Seattle for me was the quality of the coffee, I nine years old, and I got paid! I did all kinds of shows, and I also performed with must say. the Civic Light Opera. I was also in the Northwest Boy Choir and we sang this Northwest Medley, and there was a song to Ivar’s restaurant in it. When I was HOW DOES BEING A NON-DRIVER IMPACT YOUR VIEW OF THE CITY? growing up, Ivar’s had spokespeople who were dressed up in clam costumes with My favorite part about walking is that you come across things that you would pass black leggings. -

ASSOCIATION RESIDENCE for RESPECTABLE AGED INDIGENT FEMALES (Association Residence for Women), 891 Amsterdam Avenue, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission April 12, 1983 Designation List 164 LP-1280 ASSOCIATION RESIDENCE FOR RESPECTABLE AGED INDIGENT FEMALES (Association Residence for Women), 891 Amsterdam Avenue, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1881-83; Architect Richard Morris Hunt; addition 1907-08; Architect Charles A. Rich. Landmark Site: Borough of }1anhattan Tax Map Block 1855, Lot 50. On February 9, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hear ing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Association Residence for Respectable Aged Indigent Females (Association Residence for Homen), and the pro posed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 11). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Fourteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Association Residence for Respectable Aged Indigent Females, a prominent feature of the Manhattan Valley neighborhood of Manhattan's Upper West Side, was constructed in 1881-83 for one of New York City's oldest charitable institutions. The design, in a French-inspired style which recalls the Victorian Gothic, was by the "dean" of nineteenth-century American architects, Richard Monr.is Hunt. The building remains one of Hunt's few surviving significant New York City structures and a fine example of ninteenth-century institutional architecture. The Association In the midst of the nation's involvement in the War of 1812, a group of socially prominent New York City women formed an association in 1813 to aid women who were left poor wid ows by the current war or by the previous Revolutionary War. -

Technical Memo

Technical Memo To Wes Ducey, SDOT Project Manager Lisa Reid, PE, PMP/SCJ Alliance From: Marni C Heffron, PE, PTOE/Heffron Transportation Inc. Date: April 17, 2019 Project: Magnolia Bridge Planning Study Subject Alternatives Analysis Summary 1. Executive Summary The existing Magnolia Bridge currently serves to connect to and from Magnolia, Smith Cove Park/Elliott Bay Marina, Terminal 91/Elliot Bay Businesses, and 15th Ave W. The bridge serves 17,000 ADT and 3 King County Metro bus lines serving an average of 3,000 riders each weekday. The bridge was constructed 90 years ago and has deteriorated. While SDOT continues to perform maintenance to maintain public safety, the age and condition of the bridge structure means there will continue to be deterioration. In 2006, following a 4-year planning study; however, over the last decade, funding has not been identified to advance this alternative beyond 30% design. This Magnolia Bridge Planning Study identified three Alternatives to the 2006 recommend In-Kind Replacement option. These Alternatives, along with the In-Kind Replacement option, have been analyzed and compared through a multi-criteria evaluation process. Focusing on the main connections into Magnolia and Smith Cove Park/Elliott Bay Marina, the Alternatives identified are: Alternative 1: a new Armory Way Bridge into Magnolia and a new Western Perimeter Road to Smith Cove Park/Elliott Bay Marina ($200M - $350M), Alternative 2: Improvements to the existing Dravus St connection into Magnolia and a new Western Perimeter Road to Smith Cove Park/Elliott Bay Marina ($190M – $350M), Alternative 3: Improvements to the existing Dravus St connection into Magnolia and a new Garfield St bridge to Smith Cove Park/Elliott Bay Marina ($210M - $360M), and Alternative 4: In-Kind Replacement of the existing Magnolia Bridge adjacent to its current location ($340M – $420M). -

Kirtland Kelsey Cutter, Who Worked in Spokane, Seattle and California

Kirtland Kelsey 1860-1939 Cutter he Arts and Crafts movement was a powerful, worldwide force in art and architecture. Beautifully designed furniture, decorative arts and homes were in high demand from consumers in booming new cities. Local, natural materials of logs, shingles and stone were plentiful in the west and creative architects were needed. One of them was TKirtland Kelsey Cutter, who worked in Spokane, Seattle and California. His imagination reflected the artistic values of that era — from rustic chapels and distinctive homes to glorious public spaces of great beauty. Cutter was born in Cleveland in 1860, the grandson of a distinguished naturalist. A love of nature was an essential part of Kirtland’s work and he integrated garden design and natural, local materials into his plans. He studied painting and sculp- ture in New York and spent several years traveling and studying in Europe. This exposure to art and culture abroad influenced his taste and the style of his architecture. The rural buildings of Europe inspired him throughout his career. One style associated with Cutter is the Swiss chalet, which he used for his own home in Spokane. Inspired by the homes of the Bernese Oberland region of Switzerland, it featured deep eaves that extended out from the roofline. The inside was pure Arts and Crafts, with a rustic, tiled stone fireplace, stained glass windows and elegant woodwork. Its simplicity contrasted with the grand homes many of his clients requested. The railroads brought people to the Northwest looking for opportunities in mining, logging and real estate. My great grandfather, Victor Dessert, came from France and settled in Spokane in the 1880s. -

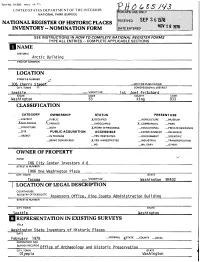

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Arctic Building AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 306 Cherry Si _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN & CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Seattle __ VICINITY OF 1 st Joel Pri tchard STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Washington 53 King 033 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH X-WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: CHG Citv Center Investors # 6 STREET & NUMBER 1906 One Washington Plaza CITY, TOWN STATE ____Tacoma VICINITY OF Washington 98402 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEED^ETC. Assessors Qff| ce , King County Admi ni s trati on Buil di nq STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Seattle Washington REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Washington State Inventory of Historic Places DATE February 1978 —FEDERAL ^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Qff1ce Of Archaeology and Historic Preservation CITY. TOWN STATE Olympia Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Arctic Building,occupying a site at the corner of Third Avenue and Cherry Street in Seattle, rises eight stories above a ground level of retail shops to an ornate terra cotta roof cornice. -

Brown V. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society

Brown v. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society Manuscript Collection No. 251 Audio/Visual Collection No. 13 Finding aid prepared by Letha E. Johnson This collection consists of three sets of interviews. Hallmark Cards Inc. and the Shawnee County Historical Society funded the first set of interviews. The second set of interviews was funded through grants obtained by the Kansas State Historical Society and the Brown Foundation for Educational Excellence, Equity, and Research. The final set of interviews was funded in part by the National Park Service and the Kansas Humanities Council. KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Topeka, Kansas 2000 Contact Reference staff Information Library & archives division Center for Historical Research KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 6425 SW 6th Av. Topeka, Kansas 66615-1099 (785) 272-8681, ext. 117 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.kshs.org ©2001 Kansas State Historical Society Brown Vs. Topeka Board of Education at the Kansas State Historical Society Last update: 19 January 2017 CONTENTS OF THIS FINDING AID 1 DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION ...................................................................... Page 1 1.1 Repository ................................................................................................. Page 1 1.2 Title ............................................................................................................ Page 1 1.3 Dates ........................................................................................................ -

Race, Housing and the Fight for Civil Rights in Los Angeles

RACE, HOUSING AND THE FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS IN LOS ANGELES Lesson Plan CONTENTS: 1. Overview 2. Central Historical Question 3. Extended Warm-Up 4. Historical Background 5. Map Activity 6. Historical Background 7. Map Activity 8. Discriminatory Housing Practices And School Segregation 9. Did They Get What They Wanted, But Lose What They Had? 10. Images 11. Maps 12. Citations 1. California Curriculum Content Standard, History/Social Science, 11th Grade: 11.10.2 — Examine and analyze the key events, policies, and court cases in the evolution of civil rights, including Dred Scott v. Sandford, Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, and California Proposition 209. 11.10.4 — Examine the roles of civil rights advocates (e.g., A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Thurgood Marshall, James Farmer, Rosa Parks), including the significance of Martin Luther King, Jr. ‘s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and “I Have a Dream” speech. 3 2. CENTRAL HISTORICAL QUESTION: Considering issues of race, housing, and the struggle for civil rights in post-World War II Los Angeles, how valid is the statement from some in the African American community looking back: “We got what we wanted, but we lost what we had”? Before WWII: • 1940s and 1950s - Segregation in housing. • Shelley v. Kraemer, 1948 and Barrows vs. Jackson, 1953 – U.S. Supreme Court decisions abolish. • Map activities - Internet-based research on the geographic and demographic movements of the African American community in Los Angeles. • Locating homes of prominent African Americans. • Shift of African Americans away from central city to middle-class communities outside of the ghetto, resulting in a poorer and more segregated central city. -

SR 520 I-5 to Medina

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: William Parsons House NPS Form llHX)O OMB No. J024-0CnB (Rev. &-&tIl t. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service •• National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See Instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking MXMinthe appropriate box or by entering the M requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter MN/A for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form to-900-a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Parsons, William, House other names/site number Harvard Mansion 2. Location street & number 2706 Harvard Ave. E. o not for publication city, town Seattle o vicinity state Washington code WA county King code 033 zip code 98102 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property IZI private IZI building(s) Contributing Noncontributing o public-local o district 2.. buildings o public-State o site sites o public-Federal o structure structures o object objects 2 a Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A listed in the National Register _0_ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this "' ~'M'" 0''''0''' tor '~.b'of .,".".