New Jersey's 2016 State Motor Fuel Tax Increase Legislation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

215Th LEGISLATIVE DISTRICTS

215th LEGISLATIVE MONTAGUE WANTAGE DISTRICTS NEW YORK SANDYSTON SUSSEX SUSSEX VERNON FRANKFORD HAMBURG BRANCHVILLE WALPACK HARDYSTON LAFAYETTE 24 FRANKLIN RINGWOOD HAMPTON WEST MILFORD STILLWATER MAHWAH OGDENSBURG PASSAIC UPPER SADDLE RAMSEY RIVER MONTVALE NEWTON 39 WANAQUE OAKLAND HARDWICK SPARTA ALLENDALE PARK FREDON RIDGE ANDOVER SADDLE RIVER FRANKLIN RIVER VALE LAKES WOODCLIFF BLOOMINGDALE LAKE OLD WALDWICK TAPPAN NORTHVALE POMPTON HILLSDALE LAKES WYCKOFF HO-HO-KUS ROCKLEIGH JEFFERSON BLAIRSTOWN MIDLAND BUTLER RIVERDALE NORWOOD PARK WASHINGTON HARRINGTON ANDOVER WESTWOOD PARK 26 KINNELON RIDGEWOOD CLOSTER EMERSON NORTH GREEN HALEDON HAWORTH GLEN ROCK ORADELL ALPINE FRELINGHUYSEN PEQUANNOCK HAWTHORNE 215th Legislature DEMAREST ROCKAWAY TWP HOPATCONG 40 PROSPECT DUMONT PARK BFAIER LAWN RGPARAMUES N CRESSKILL KNOWLTON BYRAM LINCOLN NEW WAYNE MILFORD PARK HALEDON RIVER EDGE SENATE MOUNT BOONTON TWP BERGENFIELD ASSEMBLY TENAFLY STANHOPE ALLAMUCHY ARLINGTON ELMWOOD PATERSON 38 1 NELSON ALBANO (D) 1 JEFF VAN DREW (D) 35 PARK ROCHELLE HOPE MONTVILLE PARK TOTOWA MAYWOOD ROCKAWAY DENVILLE ENGLEWOOD MATHEW MILAM (D) 2 JAMES WHELAN (D) NETCONG WHARTON SADDLE BOONTON MOUNTAIN WOODLAND BROOK 2 CHRIS BROWN (R) 3 STEPHEN SWEENEY (D) HACKENSACK LAKES PARK ENGLEWOOD FAIRFIELD LODI TEANECK JOHN AMODEO (R) CLIFFS 4 FRED MADDEN (D) DOVER LITTLE GARFIELD BOGOTA WARREN FALLS NORTH 37 3 CELESTE RILEY (D) 5 DONALD NORCROSS (D) INDEPENDENCE MOUNT OLIVE MINE HILL VICTORY CALDWELL S. HACKEN- LIBERTY ROXBURY GARDENS SACK HASBROUCK CEDAR HEIGHTS LEONIA JOHN J. BURZICHELLI (D) 6 JAMES BEACH (D) PASSAIC S. HACKENSACK RIDGEFIELD WEST GROVE PARK CALDWELL 34 TETERBORO 4 GABRIELA MOSQUERA (D) 7 DIANE ALLEN (R) FORT LEE HACKETTSTOWN MORRIS CLIFTON WALLINGTON PALISADES RANDOLPH PARSIPPANY- PARK PAUL MORIARTY (D) 8 DAWN MARIE ADDIEGO (R) PLAINS WOOD- TROY HILLS CALDWELL RIDGE VERONA MOONACHIE LITTLE 5 GILBERT WILSON (D) CHRISTOPHER CONNORS (R) CARLSTADT FERRY RIDGEFIELD 9 ROSELAND RUTHERFORD BELVIDERE S. -

ALEC in New Jersey

In NEW JERSEY !e Voice Of Corporate Special Interests in the Halls of New Jersey’s Legislature CONTENTS CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 3 KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................ 3 WHAT IS ALEC ............................................................................................................................................... 5 ALEC LEGISLATORS IN NEW JERSEY............................................................................................................... 7 AT HOME IN NEW JERSEY: ALEC CORPORATE FUNDERS .............................................................................. 9 Bayer ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 Celgene.................................................................................................................................................. 9 Daiichi‐SankyO ..................................................................................................................................... 10 HOneywell .......................................................................................................................................... -

2019 Legislative Scorecard

ENVIRONMENTAL SCORECARD OCTOBER 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR..... 3 ENVIRONMENTAL AGENDA................... 4 AT A GLANCE SCORE SUMMMARY......... 8 BILL DESCRIPTIONS............................ 12 SENATE SCORECARD........................... 18 ASSEMBLY SCORECARD....................... 23 ABOUT NEW JERSEY LCV ..................... 27 New Jersey League of Conservation Voters Board of Directors: Julia Somers, Chair Joseph Basralian, Vice Chair Carleton Montgomery, Treasurer Bill Leavens, Secretary Michele S. Byers, Trustee James G. Gilbert, Trustee Scott Rotman, Trustee Arniw Schmidt, Trustee New Jersey League of Conservation Voters Staff: Ed Potosnak, Executive Director Kaitlin Barakat, Water Quality Coordinator Dominic Brennan, Field Organizer Lee M. Clark, Watershed Outreach Manager Henry Gajda, Public Policy Director Joe Hendershot, Field Organizer Rebecca Hilbert, Policy Assistant Anny Martinez, Bi-Lingual Environmental Educator Hillary Mohaupt, Social Media Strategist and Inclusion Manager Eva Piatek, Digital Campaigns Manager Kristin Zilcosky, Director of Digital Engagement Jason Krane, Director of Development 2 DEAR FELLOW CONSERVATION VOTER, I am excited to present the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters’ 2019 Environmental Scorecard. Our scorecard rates each member of the New Jersey Senate and Assembly on their conservation record and actions taken to protect the environment in the Garden State. It does this by tracking how New Jersey’s 40 senators and 80 Assembly members voted on key legislation affecting air and water quality, open space, and the fight against climate change. As “the political voice for the environment,” New Jersey LCV uses its resources to elect environmental champions and support them in office while helping to defeat candidates and officeholders whose legislative priorities do not include air, water, and land protections. We empower legislators by providing background information before key environmental votes, and we hold legislators accountable for their positions and actions related to our environment. -

Environmental Scorecard September 2017 Table of Contents

ENVIRONMENTAL SCORECARD SEPTEMBER 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR..... 3 ENVIRONMENTAL AGENDA................... 4 AT A GLANCE SCORE SUMMMARY......... 8 BILL DESCRIPTIONS............................ 12 SENATE SCORECARD........................... 25 ASSEMBLY SCORECARD....................... 27 ABOUT NEW JERSEY LCV ..................... 31 New Jersey LeaGue of Conservation Voters Board of Directors: Debbie Mans, Chair Kelly Mooij, Vice Chair Michele Byers, Treasurer Bill Leavens, Secretary Joe Basralian, Trustee James G. Gilbert, Trustee Carleton Montgomery, Trustee Scott Rotman, Trustee Julia Somers, Trustee Jim Wyse, Trustee New Jersey LeaGue of Conservation Voters Staff: Ed Potosnak, Executive Director Kendra Baumer, Ladder of EnGaGement OrGanizer Angela Delli Santi, Communications Director Cynthia Montalvo, Development Assistant Drew Tompkins, Public Policy Coordinator Kristin Zilcosky, Director of Digital Engagement Photo By: Nicholas A. Tonelli 2 DEAR FELLOW CONSERVATION VOTER, I am pleased to present the New Jersey LeaGue of Conservation Voters’ 2017 Environmental Scorecard. The biennial scorecard provides a comprehensive, easy-to-use summary of how New Jersey’s 40 senators and 80 Assembly members voted on key leGislation affectinG air and water quality, open space, and the fight against climate change. As “the political voice for the environment,” New Jersey LCV uses its resources to elect environmental champions and support them in office, while helpinG to defeat candidates and office holders whose leGislative priorities do not include air, water, and land protections. We empower leGislators by providinG backGround information before key environmental votes, and we hold leGislators accountable for their positions and actions related to our environment. The scorecard is an important and respected component of our work. AlthouGh Governor Christie has shown himself to be no friend of the environment, New Jersey LCV has partnered with the LeGislature to achieve major policy victories in the last two years. -

Tuesday, November 5, 2019

Tuesday, November 5, 2019 Pennsylvania: 7:00 AM to 8:00 PM YOU ARE ALLOWED TO TAKE THIS GUIDE WITH YOU New Jersey: 6:00 AM to 8:00 PM INTO THE VOTING BOOTH! As long as you are in line by 8:00 PM, you have the right to vote! PENNSYLVANIA ENDORSED CANDIDATES: Superior Court: City Council At-Large: City Council (by District): Amanda Green-Hawkins (D) Helen Gym (D) 1st - Mark Squilla (D) Daniel McCaffery (D) Isaiah Thomas (D) 2nd - Kenyatta Johnson (D) Derek Green (D) 3rd - Jamie Gauthier (D) Municipal Court: Katherine Gilmore Richardson (D) 4th - Curtis Jones, Jr. (D) David Conroy (D) Dan Tinney (R) 5th - Darrell Clarke (D) Al Taubenberger (R) 6th - Bobby Henon (D) Common Pleas: 8th - Cindy Bass (D) Jennifer Schultz (D) Register of Wills: 9th - Cherelle Parker (D) Anthony Kyriakakis (D) Tracey Gordon (D) 10th - Brian O'Neill (R) Joshua Roberts (D) Tiffany Palmer (D) Sheriff: City Commissioners: Mayor of Philadelphia: James C. Crumlish (D) Rochelle Bilal (D) Omar Sabir (D) Jim Kenney (D) Carmella Jacquinto (D) Lisa Deeley (D) Crystal Powell (D) Al Schmidt (R) NEW JERSEY ENDORSED CANDIDATES: District 1: Senate Assembly Bob Andrzejczak R. Bruce Land Matthew Milam District 2: District 3: District 4: District 5: District 6: Assembly Assembly Assembly Assembly Assembly John Armato John Burzichelli Paul Moriarty William Spearman Louis Greenwald Vince Mazzeo Adam Taliaferro Gabriela Mosquera William Moen, Jr. Pamela Lampitt District 7: District 8: District 9: District 14: District 15: Assembly Assembly Assembly Assembly Assembly Carol Murphy Mark Natale Sarah Collins Wayne DeAngelo Anthony Verrelli Herb Conaway Wayne Lewis Daniel Benson Verlina Reynolds-Jackson Assistance in Voting at the Polling Place: Under federal law, if you cannot enter the voting booth or use the voting system due to a disability, you can select a person to enter the voting booth with you to provide assistance. -

2020 218Th NEW JERSEY LEGISLATURE COUNTY

2020 218th NEW JERSEY LEGISLATURE (Senators are listed first, NJEA PAC-endorsed victors are CAPITALIZED, NJEA members are bold-type) 1 Senate: Mike Testa (R); 21 JON BRAMNICK (R); NANCY MUNOZ (R) Assembly: Antwan McClellan (R); Erik Simonsen (R) 22 LINDA CARTER (D); JAMES KENNEDY (D) 2 Phil Guenther (R); John Risley (R) 23 Erik Peterson (R); John DiMaio (R) 3 John Burzichelli (D); Adam Taliaferro (D) 24 Harold Wirths (R); Parker Space (R) 4 Paul Moriarty (D); Gabriela Mosquera (D) 25 Brian Bergen (R); VACANCY (R) 5 William Spearman (D); William Moen (D) 26 BETTYLOU DECROCE (R); Jay Webber (R) 6 Louis Greenwald (D); Pamela Lampitt (D) 27 JOHN MCKEON (D); MILA JASEY (D) 7 Herb Conaway (D); Carol Murphy (D) 28 RALPH CAPUTO (D); CLEOPATRA TUCKER (D) 8 RYAN PETERS (R); JEAN STANFIELD (R) 29 Eliana Pintor Marin (D); Shanique Speight (D); 9 DiAnne Gove (R); Brian Rumpf (R) 30 SEAN KEAN (R); NED THOMSON (R) 10 Greg McGuckin (R); John Catalano (R) 31 NICHOLAS CHIARAVALLOTI (D); ANGELA MCKNIGHT (D) 11 JOANN DOWNEY (D); ERIC HOUGHTALING (D) 32 ANGELICA JIMENEZ (D); PEDRO MEJIA (D) 12 RONALD DANCER (R); ROBERT CLIFTON (R) 33 ANNETTE CHAPARRO (D); RAJ MUKHERJI (D) 13 SERENA DIMASO (R); GERALD SCHARFENBERGER (R) 34 THOMAS GIBLIN (D); BRITNEE TIMBERLAKE (D) 14 WAYNE DEANGELO (D); DANIEL BENSON (D) 35 SHAVONDA SUMTER (D); BENJIE WIMBERLY (D) 15 VERLINA REYNOLDS-JACKSON (D); ANTHONY VERRELLI (D) 36 GARY SCHAER (D); CLINTON CALABRESE (D) 16 ANDREW ZWICKER (D); ROY FREIMAN (D) 37 VALERIE HUTTLE (D); GORDON JOHNSON (D) 17 Joseph Egan (D); JOE DANIELSEN(D) -

Legislative Report Card 218Th Nj Legislature 2018-2019 Dear Friends

LEGISLATIVE REPORT CARD 218TH NJ LEGISLATURE 2018-2019 DEAR FRIENDS, I am pleased to share this report card for the 2018-2019 New Jersey state legislature. Here is a snapshot of how lawmakers voted on key social and moral legislation related to the right to life, education, family, marijuana, marriage, and other issues. Guided by our mission of building a state where God is honored, religious liberty flourishes, families thrive, and life is cherished, this report card focuses on seven bills in the New Jersey Assembly and Senate during the 2018-2019 Legislative Session. All of those bills are included in this report card. A bill is passed by a simple majority in the Senate (21 votes out of 40 senators) and the Assembly (41 votes out of 80 Assembly members.) Lawmakers earned letter grades ranging from A–F based on how they voted on all the bills. This report card is not an endorsement of any candidate or political party. It does not measure any lawmakers’ integrity, commitment to their faith, work ethic, or rapport with Family Policy Alliance of New Jersey. It is only a report on how each lawmaker voted. One of the most common questions people ask is, “How did my legislator vote?” This report card should help you answer that question. Sincerely, Shawn Hyland Director of Advocacy CONTENTS Introduction Letter 2 Vote Descriptions 4 About the Report Card 3 Legislator Votes 5-7 - 2 - ABOUT THE REPORT CARD Family Policy Alliance of New Jersey selected votes on key legislation in the New Jersey Assembly and New Jersey Senate based on our core belief in promoting, protecting, and strengthening traditional family values. -

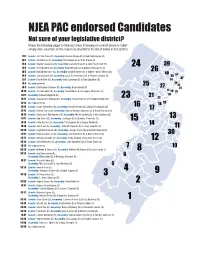

NJEA PAC Endorsed Candidates Not Sure of Your Legislative District? Check the Following Pages to Find Your Town

NJEA PAC endorsed Candidates Not sure of your legislative district? Check the following pages to find your town. If viewing on a smart phone or tablet simply click a number on the map to be directed to the list of towns in that district. LD 1 Senate: Jeff Van Drew (D); Assembly: Nelson Albano (D) & Bob Andrzejczak (D) LD 2 Senate: Jim Whelan (D); Assembly: Nick Russo (D) & Chris Brown (R) LD 3 Senate: Stephen Sweeney (D); Assembly: Celeste Riley (D) & John Burzichelli (D) 24 39 LD 4 Senate: Fred Madden (D); Assembly: Paul Moriarty (D) & Gabriela Mosquera (D) LD 5 Senate: Donald Norcross (D); Assembly: Angel Fuentes (D) & Gilbert “Whip” Wilson (D) 26 40 38 LD 6 Senate: James Beach (D); Assembly: Louis D. Greenwald (D) & Pamela Lampitt (D) 35 LD 7 Senate: Diane Allen (R); Assembly: Herb Conaway (D) & Troy Singleton (D) 34 37 36 LD 8 No endorsements 25 32 LD 9 Senate: Christopher Connors (R); Assembly: Brian Rumpf (R) 27 33 28 LD 10 Senate: Jim Holzapfel (R); Assembly: David Wolfe (R) & Gregory McGuckin (R) 29 31 LD 11 Assembly: Edward Zipprich (D) 20 23 21 22 LD 12 Senate: Raymond D. Dothard (D); Assembly: Ronald Dancer (R) & Robert Clifton (R) LD 13 No endorsements 18 19 LD 14 Senate: Linda Greenstein (D); Assembly: Daniel Benson (D) & Wayne DeAngelo (D) 16 LD 15 Senate: Shirley Turner (D); Assembly: Bonnie Watson Coleman (D) & Reed Gusciora (D) 17 LD 16 Senate: Christian R. Mastondrea (D); Assembly: Marie Corfield (D) & Ida Ochoteco (D) 13 LD 17 Senate: Bob Smith (D); Assembly: Joe Egan (D) & Upendra Chivukula (D) 15 LD 18 Senate: Peter Barnes (D); Assembly: Pat Diegnan (D) & Nancy Pinkin (D) 14 LD 19 Senate: Joe Vitale (D); Assembly: John Wisniewski (D) & Craig Coughlin (D) 11 LD 20 Senate: Raymond Lesniak (D); Assembly: Joseph Cryan (D) & Annette Quijano (D) LD 21 Senate: Thomas Kean, Jr. -

Labor Fax Co-Editors: Charles Wowkanech Laurel Brennan President Secretary-Treasurer Associate Editors: Angela Delli Santi & Lee Sandberg

Labor Fax Co-Editors: Charles Wowkanech Laurel Brennan President Secretary-Treasurer Associate Editors: Angela Delli Santi & Lee Sandberg (609) 989-8730 • www.njaflcio.org 1998 Labor Fax APEX Award November 3, 2015 Volume 19 Issue 1 ELECTION DAY / SPECIAL EDITION NJ AFL-CIO Makes History with Record —— ELECTION HIGHLIGHTS —— Number of Labor Candidates Elected; Democrats Expand Assembly Majority – Labor Prevails in District 11 Upset LABOR DELIVERS FOR HOUGHTALING (IBEW 400) 47 – Labor Candidate Victories (NEW RECORD) AND DOWNEY IN DISTRICT 11 The New Jersey State AFL-CIO’s political education pro- 70% – Labor Candidate Win-Rate gram is second to none, and the outstanding results of the November 3 election keep our momentum strong heading 864 – Labor Candidate Victories Since 1997 into the 2016 presidential race. We led union brothers and sisters to victories across the state, from school board and town council races to mayor, freeholder and state Assembly – Democrats Expand Assembly Majority seats. A record 47 union members won their elections, a phe- nomenal win ratio of 70% for labor candidates on the ballot. No one delivers election results like our labor candidates 2015 General Election Results program, which raised its total of election victories to 864! DISTRICT 1 DISTRICT 2 In a remarkable upset, Eric Houghtaling of IBEW 400 and his running mate JoAnn Downey unseated GOP incumbents, Bob Andrzejczak (D)*◊ Vincent Mazzeo (D)*◊ taking control of District 11 for the first time in 20 years. R. Bruce Land (D) Chris Brown (R)* Additionally, five incumbent labor officials all won re- election: Thomas Giblin, IUOE 68; Joseph Egan, IBEW 456; DISTRICT 3 DISTRICT 4 Wayne DeAngelo, IBEW 269; Troy Singleton, UBC 715; and Paul Moriarty, AFTRA/SAG. -

Nov/Dec 06 2/25/13 12:01 PM Page 14

246277_ANJRPC MAR-APR 2013_nov/dec 06 2/25/13 12:01 PM Page 14 Prepared by the Association of New Jersey Rifle & Pistol Clubs NJ LEGISLATIVE ROSTER 2012-2013 www.anjrpc.org District: 1 District: 12 Senator JEFF VAN DREW (D) (609) 465-0700 - Email: [email protected] Senator SAM THOMPSON (R) (732) 607-7580 - Email: [email protected] Assemblyman NELSON ALBANO (D) (609) 465-0700 - Email: [email protected] 2501 Highway 516, Suite 101, Old Bridge, NJ 08857 Assemblyman MATTHEW MILAM (D) (609) 465-0700 - Email: [email protected] Assemblyman ROB CLIFTON (R) (732) 446-3408 - Email: [email protected] All: 21 North Main Street, Cape May Court House, NJ 08210-2154 516 Route 33 West, Bldg. 2, Suite 2, Millstone, NJ 08535 Assemblyman RON DANCER (R) (609) 758-0205 - Email: [email protected] District: 2 405 Rt. 539, Cream Ridge, NJ 08514 Senator JIM WHELAN (D) (609) 383-1388 - Email: [email protected] 511 Tilton Road, Northfield, NJ 08225 District: 13 Assemblyman JOHN F. AMODEO (R) (609) 677-8266 - Email: [email protected] Senator JOSEPH KYRILLOS (R) (732) 671-3206 - Email: [email protected] 1801 Zion Road, Northfield, NJ 08225 One Arin Park Building, 1715 Highway 35, Suite 303, Middletown, NJ 07748 Assemblyman CHRIS A. BROWN (R) (609) 677-8266 - Email: [email protected] Assemblywoman AMY HANDLIN (R) (732) 787-1170 - Email: [email protected] 1801 Zion Road, Suite 1, Northfield, NJ 08225 890 Main Street, Belford, NJ 07718 Assemblyman DECLAN O’SCANLON (R) (732) 933-1591 - Email: [email protected] District: 3 32 Monmouth St., 3rd Floor, Red Bank, NJ 07701 Senator STEPHEN SWEENEY (D) (856) 251-9801 - Email: [email protected] Kingsway Commons, 935 Kings Highway, Suite 400, Thorofare, NJ 08086 District: 14 Assemblyman JOHN BURZICHELLI (D) (856) 251-9801 - Email: [email protected] Senator LINDA GREENSTEIN (D) (609) 395-9911 - Email: [email protected] Kingsway Commons, 935 Kings Highway, Suite 400, Thorofare, NJ 08086 7 Centre Drive, Suite 2, Monroe Township, NJ 08831 Assemblywoman CELESTE M. -

Assembly Committee Assignments

For Release Contact Jan. 9, 2018 Majority Press Office 609.847.3500 Speaker Coughlin Announces New Assembly Committee Chairs & Membership for 218th Legislative Session (TRENTON) – Assembly Speaker Craig J. Coughlin on Tuesday announced the chairs and Democratic composition of each Assembly standing reference committee for the 218th legislative session, which begins today. “We are fortunate to have such a dynamic group of individuals with diverse backgrounds in our caucus,” said Coughlin (D-Middlesex). “This has enabled us to put together an outstanding team that will help guide our policy agenda for the next two years. I have every confidence that each chair and their respective members will work tirelessly to shepherd through a progressive agenda that prioritizes the needs of New Jersey’s working families while pursuing innovative ways to protect and maximize taxpayer dollars.” The Democratic composition of each reference committee is as follows: AGRICULTURE Bob Andrzejczak, Chair Eric Houghtaling, Vice-Chair Adam Taliaferro APPROPRIATIONS John Burzichelli, Chair Gary Schaer, Vice-Chair Gabriela Mosquera Herb Conaway Cleopatra Tucker John McKeon Wayne DeAngelo BUDGET Eliana Pintor Marin, Chair John Burzichelli, Vice-Chair Carol Murphy Daniel Benson Patricia Egan Jones Raj Mukherji Benjie Wimberly Gordon Johnson COMMERCE Gordon Johnson, Chair Robert Karabinchak, Vice-Chair John Armato Roy Freiman James Kennedy Eliana Pintor Marin Nicholas Chiaravalloti CONSUMER AFFAIRS Paul Moriarty, Chair Raj Mukherji, Vice-Chair Annette Chaparro EDUCATION -

Passaic County Directory

facebook.com/passaiccountynj @passaic_county instagram.com/passaiccountynj youtube.com/user/passaiccountynj Subscribe! www.passaiccountynj.org 2018 Passaic County Directory • Updated as of Feb 2018 • 1st Edition Published by the Passaic County Board of Chosen Freeholders Passaic County Administration Building 401 Grand Street • Paterson, New Jersey 07505 1 Administration Building 401 Grand Street, Paterson, NJ 07505 Hours: 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Monday through Friday Main Number: 973-881-4000 Special Thanks to Passaic County Technical Institute 2 Table of Contents Map of Passaic County..................................................4 Government Officials....................................................5 The Role of the Freeholders..........................................6 Freeholder Director’s Message......................................8 The 2018 Board of Chosen Freeholders........................9 Freeholder Standing Committees.................................16 Administration/Constitutional Officers.......................17 Departments and Affiliated Offices.............................18 Superior Court.............................................................57 Federal Officials..........................................................60 State Officials .............................................................62 Municipalities..............................................................65 Boards/Agencies/Commissions...................................82 Parks and Recreational Facilities.................................91