Terrorist Trial Report Card

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amicus Brief for Aref and Hossain

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK YASSIN AREF, Petitioner, Case No. 1:04-CR-402 (TJM) V. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. MOHAMMED MOSHARREF HOSSAIN, Petitioner, Case No. 1:04-CR-402 (TJM) V. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. Proposed AMICUS BRIEF Project SALAM, the Muslim Solidarity Committee And the Masjid As Salaam ________________________________________________________________________ On October 10, 2006, Yassin Muhidden Aref (hereinafter “Aref”), and Mohammed Mosharref Hossain (hereinafter “Hossain”) were convicted of terrorism-related charges in connection with an FBI sting involving the sale of a fake missile for a fictitious terrorist attack, and for money laundering. Aref was also convicted of one count of lying to the FBI. On March 8, 2007 the two defendants were sentenced to 15 years incarceration each. Their appeals to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and to the U.S. Supreme Court were denied, and they have exhausted their appellate remedies. Aref and Hossain have petitioned this court pursuant to the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, Section 2255 for, among other issues, the appointment of an independent prosecutor to review their cases to determine if the government and the courts provided them with necessary exculpatory information, a fair trial and justice. They seek relief similar to what was granted in People v. Theodore Stevens (a Stevens review), or what the Inspector General of the Department of Justice recommended in his June 10, 2009 Report to correct the failure of the Justice Department to identify and provide exculpatory information in terrorism cases – an independent review. Amici, Muslim Solidarity Committee (hereinafter “MSC”), Project SALAM (hereinafter “SALAM”), and the Masjid As-Salaam respectfully submit this Amicus brief, pursuant to Rule 29 in support of the defendants 2255 petition and to present information which may assist the court in deciding the issues raised by the defendants, especially where the defendants are unrepresented. -

The War on Terror As a Self-Inflicted Disaster Ian S

*ğĕĖġĖğĕĖğĥ 3065*/( 10-*$:3&1035 Our Own Strength Against Us The War on Terror as a Self-Inflicted Disaster Ian S. Lustick* April 2008 &YFDVUJWF4VNNBSZ The War on Terror is much more than a colos- serious terrorist threat cannot even be a topic of sal waste. It is the most potent threat Americans public discussion. Politicians, the news media, face to their liberties and security. With one rival government agencies, defense contractors, spectacular blow al-Qaeda managed to exploit lobbyists of all kinds, universities, and the enter- the fantasies of a “New American Century” ca- tainment industry battle ferociously to increase bal inside the Bush administration and sucker revenues and pump up reputations by posing as the American people and its leaders into a re- more committed to winning the War on Terror sponse that serves its interests. The overstated, than their competitors. Frustrated by their in- but publicly honored, “War on Terror” and the ability to find any evidence of serious terrorist catastrophic invasion of Iraq associated with it activities in the U.S., law enforcement and re- rescued the jihadi movement from oblivion by lated agencies escalate techniques of pre-emp- convincing most of the Muslim world that ji- tive prosecution and entrapment to justify their hadi propaganda about the “infidel Christians enormous budgets. and Jews” was actually correct. Terror is a problem, but the War on Terror, At home, Americans have been so bam- because it turns U.S. power against America, is boozled by the hysterical imagery of the War on a catastrophe. Terror that the absence of evidence of a truly *Ian S. -

Witness to Abuse Human Rights Abuses Under the Material Witness Law Since September 11

Human Rights Watch June 2005 Vol. 17, No. 2 (G) Witness to Abuse Human Rights Abuses under the Material Witness Law since September 11 Summary......................................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations......................................................................................................................... 7 To the Justice Department ...................................................................................................... 7 To Congress............................................................................................................................... 8 To the Judiciary......................................................................................................................... 9 I. The Material Witness Law: Overview and Pre-September 11 Use.................................. 10 Overview of the Material Witness Law ............................................................................... 12 Arrest of Material Witnesses before September 11 ........................................................... 14 II. Post-September 11 Material Witness Detention Policy................................................... 15 III. Misuse of the Material Witness Law to Hold Suspects as Witnesses........................... 17 Suspects Held as Witnesses................................................................................................... 20 Prolonged Incarceration and Undue Delays in Presenting Witnesses -

Hitler's Doubles

Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos Fully-Illustrated Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles: Fully-Illustrated By Peter Fotis Kapnistos [email protected] FOT K KAPNISTOS, ICARIAN SEA, GR, 83300 Copyright © April, 2015 – Cold War II Revision (Trump–Putin Summit) © August, 2018 Athens, Greece ISBN: 1496071468 ISBN-13: 978-1496071460 ii Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos © 2015 - 2018 This is dedicated to the remote exploration initiatives of the Stargate Project from the 1970s up until now, and to my family and friends who endured hard times to help make this book available. All images and items are copyright by their respective copyright owners and are displayed only for historical, analytical, scholarship, or review purposes. Any use by this report is done so in good faith and with respect to the “Fair Use” doctrine of U.S. Copyright law. The research, opinions, and views expressed herein are the personal viewpoints of the original writers. Portions and brief quotes of this book may be reproduced in connection with reviews and for personal, educational and public non-commercial use, but you must attribute the work to the source. You are not allowed to put self-printed copies of this document up for sale. Copyright © 2015 - 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Hitler’s Doubles The Cold War II Revision : Trump–Putin Summit [2018] is a reworked and updated account of the original 2015 “Hitler’s Doubles” with an improved Index. Ascertaining that Hitler made use of political decoys, the chronological order of this book shows how a Shadow Government of crisis actors and fake outcomes operated through the years following Hitler’s death –– until our time, together with pop culture memes such as “Wunderwaffe” climate change weapons, Brexit Britain, and Trump’s America. -

Scare Tactics: Ashcroft's Phony 'War on Terrorism'

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 31, Number 12, March 26, 2004 EIRNational Scare Tactics: Ashcroft’s Phony ‘War on Terrorism’ by Edward Spannaus Once described as America’s “de facto Minister of Fear,” Convictions Without Trials Attorney General John Ashcroft fit that description in a state- The fraud of Ashcroft’s “war on terrorism” was dramati- ment issued on March 4, immediately after the conviction cally demonstrated in December, when a research institute of three defendants in the “Virginia Jihad” case. Ashcroft associated with Syracuse University, the Transactional Re- declared: “Today, Americans get a glimpse of what is hiding cords Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), published a study in the shadows. Terrorists recruit, train, and finance jihad which blew a major hole in Ashcroft’s scare campaign about in America.” “Islamic terrorists” and “sleeper cells” inside the United The truth is that Ashcroft’s “war on terrorism” gives no States. The study showed that there had been a sharp increase such glimpse; it is a gigantic dud. The blunderbus tools given in the number of convictions in serious terrorism cases in the by Congress to the Justice Department have enabled Ashcroft two years following the 9/11 attacks, from 96 for the two and Co. to use the threat of draconian prison sentences to years prior to September 2001, to 341 for the two years after. force defendants to plead guilty to offenses that they may or What was most surprising about the Syracuse study was what may have not committed. As a result, the Justice Department it showed about sentences. -

30 Terrorist Plots Foiled: How the System Worked Jena Baker Mcneill, James Jay Carafano, Ph.D., and Jessica Zuckerman

No. 2405 April 29, 2010 30 Terrorist Plots Foiled: How the System Worked Jena Baker McNeill, James Jay Carafano, Ph.D., and Jessica Zuckerman Abstract: In 2009 alone, U.S. authorities foiled at least six terrorist plots against the United States. Since Septem- ber 11, 2001, at least 30 planned terrorist attacks have Talking Points been foiled, all but two of them prevented by law enforce- • At least 30 terrorist plots against the United ment. The two notable exceptions are the passengers and States have been foiled since 9/11. It is clear flight attendants who subdued the “shoe bomber” in 2001 that terrorists continue to wage war against and the “underwear bomber” on Christmas Day in 2009. America. Bottom line: The system has generally worked well. But • President Obama spent his first year and a half many tools necessary for ferreting out conspiracies and in office dismantling many of the counterter- catching terrorists are under attack. Chief among them are rorism tools that have kept Americans safer, key provisions of the PATRIOT Act that are set to expire at including his decision to prosecute foreign ter- the end of this year. It is time for President Obama to dem- rorists in U.S. civilian courts, dismantlement of onstrate his commitment to keeping the country safe. Her- the CIA’s interrogation abilities, lackadaisical itage Foundation national security experts provide a road support for the PATRIOT Act, and an attempt map for a successful counterterrorism strategy. to shut down Guantanamo Bay. • The counterterrorism system that has worked successfully in the past must be pre- served in order for the nation to be successful In 2009, at least six planned terrorist plots against in fighting terrorists in the future. -

In Pursuit of Justice Prosecuting Terrorism Cases in the Federal Courts 2009 Update and RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

In Pursuit of Justice Prosecuting Terrorism Cases in the Federal Courts 2009 UPDATE AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS Richard B. Zabel James J. Benjamin, Jr. July 2009 About Us Human Rights First believes that building respect for human rights and the rule of law will help ensure the dignity to which every individual is entitled and will stem tyranny, extremism, intolerance, and violence. Human Rights First protects people at risk: refugees who flee persecution, victims of crimes against humanity or other mass human rights violations, victims of discrimination, those whose rights are eroded in the name of national security, and human rights advocates who are targeted for defending the rights of others. These groups are often the first victims of societal instability and breakdown; their treatment is a harbinger of wider-scale repression. Human Rights First works to prevent violations against these groups and to seek justice and accountability for violations against them. Human Rights First is practical and effective. We advocate for change at the highest levels of national and international policymaking. We seek justice through the courts. We raise awareness and understanding through the media. We build coalitions among those with divergent views. And we mobilize people to act. Human Rights First is a non-profit, nonpartisan international human rights organization based in New York and Washington D.C. To maintain our independence, we accept no government funding. This report is available for free online at www.humanrightsfirst.org © 2009 Human Rights First. All Rights Reserved. Headquarters Washington D.C. Office 333 Seventh Avenue 100 Maryland Avenue, NE 13th Floor Suite 500 New York, NY 10001-5108 Washington, DC 20002- 5625 Tel.: 212.845.5200 Tel: 202.547.5692 Fax: 212.845.5299 Fax: 202.543.5999 www.humanrightsfirst.org In Pursuit of Justice: 2009 Update Preface As the Obama Administration takes steps to shut down analyzed 119 cases with 289 defendants. -

N:\Spaul\Newsrel\Anti-Terrorism\Finton Release

Acting United States Attorney Jeffrey B. Lang Central District of Illinois FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: SHARON PAUL THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2009 PHONE: (217) 492-4450 www.usdoj.gov/usao/ilc/ ILLINOIS MAN ARRESTED IN PLOT TO BOMB COURTHOUSE AND MURDER FEDERAL EMPLOYEES -- Vehicle Bomb Placed at Scene Was Inactive and Posed No Danger to Public -- SPRINGFIELD – Acting U.S. Attorney Jeffrey B. Lang of the Central District of Illinois and Karen E. Spangenberg, Special Agent in Charge of the FBI, Springfield Division, today announced that Michael C. Finton, a.k.a., “Talib Islam,” has been arrested on charges of attempted murder of federal employees and attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction (explosives) in connection with a plot to detonate a vehicle bomb at the federal building in Springfield, Ill. In his alleged efforts to carry out the plot, Finton ultimately dealt with undercover FBI agents and confidential sources who continuously monitored his activities up to the time of the arrest. Further, in his alleged efforts, Finton drove a vehicle containing inactive explosives to the Paul Findley Federal Building and Courthouse in Springfield and attempted to detonate them, according to a criminal complaint filed today in the Central District of Illinois. The arrest of Finton is not in any way related to the ongoing terror investigation in New York and Colorado. Finton, 29, a resident of Decatur, Ill., is charged in the criminal complaint with one count of attempted murder of federal officers or employees and attempted use a weapon of mass destruction. If convicted, he faces a maximum penalty of life in prison. -

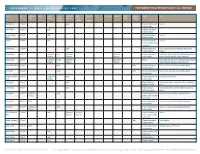

Terrorist Trial Report Card: U.S. Edition – Appendix B

SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 – SEPTEMBER 11, 2006 TERRORIST TRIAL REPORT CARD: U.S. EDITION Name Date Commercial Drugs General General Immigration National Obstruction Other Racketeering Terrorism Violent Weapons Sentence Notes Fraud Fraud Criminal Violations Security of Crimes Violations Conspiracy Violations Investigation Khalid Al Draibi 12-Sep-01 Guilty 4 months imprisonment, 36 Deported months probation Sherif Khamis 13-Sep-01 Guilty 2.5 months imprisonment, 36 months probation Jean-Tony Antoine 14-Sep-01 Guilty 12 months imprisonment, Deported Oulai 24 months probation Atif Raza 17-Sep-01 Guilty 4.7 months imprisonment, Deported 36 months probation, $4,183 fine/restitution Francis Guagni 17-Sep-01 Guilty 20 months imprisonment, French national arrested at Canadian border with box cutter; 36 months probation Deported Ahmed Hannan 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Guilty Acquitted or Acquitted or 6 months imprisonment, 24 Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed months probation Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Karim Koubriti 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Pending Acquitted or Acquitted or Pending Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Vincente Rafael Pierre 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 24 months imprisonment, Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, Traci Elaine Upshur) 36 months probation Traci Upshur 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 15 months imprisonment, 24 Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, -

Borderless World, Boundless Threat:Online Jihadists and Modern

BORDERLESS WORLD, BOUNDLESS THREAT: ONLINE JIHADISTS AND MODERN TERRORISM A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Security Studies By Spencer O. Hayne, B.A. Washington, DC November 19, 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Spencer O. Hayne All Rights Reserved ii BORDERLESS WORLD, BOUNDLESS THREAT: ONLINE JIHADISTS AND MODERN TERRORISM Spencer O. Hayne, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Justine A. Rosenthal, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The online jihadist community represents a new phenomenon in the global spread of Islamic radicalism. Many terrorism experts largely ignore the fact that the Internet is more than just a tool for established terrorist organizations—it can be a platform for the evolution of the jihadist social movement itself. While the majority of this movement’s members are casual supporters of a global Islamist jihad against the West, a number of the community’s members have already proven willing to take their virtual beliefs into the real world through terrorist acts. Many of these terrorists have attracted significant media attention—Jihad Jane, the Christmas Day Bomber, the Fort Hood Shooter, the attack on CIA agents in Afghanistan, the Times Square Bomber, and a number of other “homegrown” terrorists. The individuals perpetrating these terrorist acts are as diverse as they are dangerous, presenting a significant challenge to counterterrorism officials and policymakers. This study profiles 20 recent cases of online jihadists who have made the transition to real-world terrorism along a number of characteristics: age, ethnicity, immigration status, education, religious upbringing, socio-economic class, openness about beliefs, suicidal tendencies, rhetoric focus, location, target, terrorist action, offline and online activity, and social isolation or the presence of an identity crisis. -

The Terrorist Is a Star!: Regulating Media Coverage of Publicity- Seeking Crimes

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 60 Issue 3 Article 3 6-2008 The Terrorist Is A Star!: Regulating Media Coverage of Publicity- Seeking Crimes Michelle Ward Ghetti Southern University Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Communications Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Ghetti, Michelle Ward (2008) "The Terrorist Is A Star!: Regulating Media Coverage of Publicity-Seeking Crimes," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 60 : Iss. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol60/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Terrorist Is A Star!: Regulating Media Coverage of Publicity-Seeking Crimes Michelle Ward Ghetti* I. P REFA CE ...................................................................................482 II. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 487 III. THE PROBLEM OF MEDIA COVERAGE OF PUBLICITY-SEEKING CRIMES ................................................... 490 A . Intimidation ...................................................................... 495 B. Im itation.......................................................................... -

STINGS, STOOLIES, and AGENTS PROVOCATEURS: EVALUATING FBI UNDERCOVER COUNTERRORISM OPERATIONS a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty

STINGS, STOOLIES, AND AGENTS PROVOCATEURS: EVALUATING FBI UNDERCOVER COUNTERRORISM OPERATIONS A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Security Studies By Joseph Bertini, B.A. Washington, DC April 15, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Joseph Bertini All Rights Reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Literature Review............................................................................................................. 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 4 Data and Methods .......................................................................................................... 13 Analysis.......................................................................................................................... 17 Conclusions and Recommendations .............................................................................. 30 Appendix ........................................................................................................................ 36 Bibliography ................................................................................................................... 44 iii I. Introduction After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) dramatically