ANNUAL REPORT 2010-11 (English Version) ------Submitted Before the Annual General Meeting Held on 21 August 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(AQAR) 2008-09 to the NAAC Authorities for Their Perusal

D V S College of Arts & Science, Shimoga. MOTTO OF D V S 'ADAPT AND EXCEL’ The institution adapts to the changing time and tries to excel in all aspects of the education. LOGO OF D V S The logo is framed keeping in mind the vision and mission of the institution. It also reflects the great ideals of education as perceived by the ancient Indian scholars. Teacher is placed at the centre as he is the key factor in the field of education. The rays around him suggest the spread of wisdom and enlightenment. The Vyasa Peetha in front of the Guru is the symbol of knowledge, which the institution spreads. The logo, which is circular in its shape, reflects wholeness and completeness. The swans on either side symbolize reason and thought. The swans, which rise above, suggest the upward movement of one's life from the lower level. This logo sums up the goal of our Institution. Therefore this logo has been adopted and sincerely emulated. || Panditaha Samadarshinaha || Explanation: A learned man has an integrated vision of life. AQAR – 2008-09 1 D V S College of Arts & Science, Shimoga. VISION To strive to become an institution of excellence in the field of higher education, to provide value-based, career oriented education to ensure integrated development of human potential for the service of mankind. MISSION Our mission is to realize our vision through 1. Promoting and facilitating education in conformity with the statutory and regulatory requirements. 2. Planning and establishing necessary infrastructure and learning resources. 3. Supporting faculty development programmes and continuing education programs. -

Dist. Name Name of the NGO Registration Details Address Sectors Working in Shimoga Vishwabharti Trust 411, BOOK NO. 1 PAGE 93/98

Dist. Name Name of the NGO Registration details Address Sectors working in Agriculture,Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries,Biotechnology,Children,Education & NEAR BASAWESHRI TEMPLE, ANAVATTI, SORABA TALUK, Literacy,Aged/Elderly,Health & Family Shimoga vishwabharti trust 411, BOOK NO. 1 PAGE 93/98, Sorbha (KARNATAKA) SHIMOGA DIST Welfare,Agriculture,Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries,Biotechnology,Children,Civic Issues,Disaster Management,Human Rights The Shimoga Multipurpose Social Service Society "Chaitanya", Shimoga The Shimoga Multipurpose Social Service Society 56/SOR/SMG/89-90, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Education & Literacy,Aged/Elderly,Health & Family Welfare Alkola Circle, Sagar Road, Shimoga. 577205. Shimoga The Diocese of Bhadravathi SMG-4-00184-2008-09, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Bishops House, St Josephs Church, Sagar Road, Shimoga Education & Literacy,Health & Family Welfare,Any Other KUMADVATHI FIRST GRADE COLLEGE A UNIT OF SWAMY Shimoga SWAMY VIVEKANANDA VIDYA SAMSTHE 156-161 vol 9-IV No.7/96-97, SHIKARIPURA (KARNATAKA) VIVEKANANDA VIDYA SAMSTHE SHIMOGA ROAD, Any Other SHIKARIPURA-577427 SHIMOGA, KARNATAKA Shimoga TADIKELA SUBBAIAH TRUST 71/SMO/SMG/2003, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Tadikela Subbaiah Trust Jail Road, Shimoga Health & Family Welfare NIRMALA HOSPITALTALUK OFFICE ROADOLD Shimoga ST CHARLES MEDICAL SOCIETY S.No.12/74-75, SHIMOGA (KARNATAKA) Data Not Found TOWNBHADRAVATHI 577301 SHIMOGA Shimoga SUNNAH EDUCATIONAL AND CHARITABLE TRUST E300 (KWR), SHIKARIPUR (KARNATAKA) JAYANAGAR, SHIKARIPUR, DIST. SHIMOGA Education & Literacy -

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka. Final Report.Pdf

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Study of SMALL SCHOOLS IN KARNATAKA FFiinnaall RReeppoorrtt Submitted to: O/o State Project Director, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Karnataka 15th September 2010 Catalyst Management Services Pvt. Ltd. #19, 1st Main, 1st Cross, Ashwathnagar RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560 094, India SSA Mission, Karnataka CMS, Bangalore Ph.: +91 (080) 23419616 Fax: +91 (080) 23417714 Email: raghu@cms -india.org: [email protected]; Website: http://www.catalysts.org Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Acknowledgement We thank Smt. Sandhya Venugopal Sharma,IAS, State Project Director, SSA Karnataka, Mr.Kulkarni, Director (Programmes), Mr.Hanumantharayappa - Joint Director (Quality), Mr. Bailanjaneya, Programme Officer, Prof. A. S Seetharamu, Consultant and all the staff of SSA at the head quarters for their whole hearted support extended for successfully completing the study on time. We also acknowledge Mr. R. G Nadadur, IAS, Secretary (Primary& Secondary Education), Mr.Shashidhar, IAS, Commissioner of Public Instruction and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar, IAS, Secretary (Planning) for their support and encouragement provided during the presentation on the final report. We thank all the field level functionaries specifically the BEOs, BRCs and the CRCs who despite their busy schedule could able to support the field staff in getting information from the schools. We are grateful to all the teachers of the small schools visited without whose cooperation we could not have completed this study on time. We thank the SDMC members and parents who despite their daily activities were able to spend time with our field team and provide useful feedback about their schools. -

Charaka Women's Multipurpose Cooperative Society1

WORKING PAPER NO: 333 Charaka Women’s Multipurpose Cooperative Society1 BY Rajalaxmi Kamath Assistant Professor, Centre for Public Policy Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore – 5600 76 Ph: 080-26993748 [email protected] & Smita Ramanathan Research Associate Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore – 5600 76 [email protected] Year of Publication 2011 1 Charaka Women’s Multipurpose Cooperative Society1. Charaka Women’s Multipurpose Cooperative Society. 1. Background We have been patrons of the Desi Apparel Stores at South End Circle in Bangalore, where we have been getting our handloom jubbas (kurtas) and other ready-to-wear cotton and handloom garments at very reasonable prices. We came to know that the main production unit for Desi is a rural women’s cooperative society called Charaka, based in the village of Heggodu in Shivamogga district of Karnataka. Charaka, we were told, was an initiative of the Kannada playwright and author Prasanna. The question of what makes successful cooperatives tick had always intrigued us and also wanting to know more about the jubbas that we liked wearing, we gathered information about Charaka and reached Heggodu for the first time in April 2009. The first impression of Charaka was very soothing to our jaded, urban eyes. Rustic, red mud and brick structures with artistic drawing on panels (which we later came to know was a folk-art called hase-kale), all around a huge banyan tree with chirpy young women ambling purposefully across the place. Since that day, we have been visiting Charaka often, and we have been drawn to the spirit of Charaka and the lively women who own and run that Institution. -

Building Bright Futures 2019: Arizona’S Early Childhood Opportunities Report

Building Bright Futures 2019: Arizona’s Early Childhood Opportunities Report Table of Contents Introduction 4-5 The Big Picture of Arizona’s Little Kids 6-9 Early Adversity Threatens Long-term Success 10-16 Data Summary: Family Characteristics 17-29 Data Summary: Economic Circumstances 30-41 Language & Literacy: The Foundation of Success 42-50 Data Summary: Education 51-69 Taking A Shot Against Disease 70-74 Data Summary: Child Health and Well-Being 75-91 Data Summary Endnotes 92-97 Acknowledgements 98 Introduction 4 | First Things First was created by Arizonans to help ensure that Arizona children have the opportunity to arrive at kindergarten prepared to be successful. Each year, the statewide First Things First Board and its affiliated regional partnership councils make decisions about which early childhood strategies to fund that will impact the health and school readiness of Arizona’s children. First Things First is not alone in its mission. Early childhood stakeholders – including parents and caregivers, child care and health providers, state and non-profit agencies, educators, businesses, philanthropists, faith organizations, policymakers and elected leaders – are partners in addressing children’s school readiness. Decisions made by all early childhood stakeholders must be based on science and evidence – about how our children are doing, the resources communities have, and the needs of children in different areas of the state. Building Bright Futures is a valuable tool to inform those decisions. Data presented in this report cover a myriad of topics – some directly related to children, their health and their learning; others that describe the circumstances and environments in which children live. -

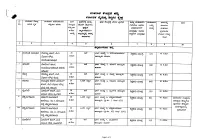

KSWTC List of Polling Stations

m.C7IR1 "fO~c.1 1111"1. ~ wmr6J.. 1I1.G).. a~wa t'! r--:~::;-.~----:ilJ3:=.s~ca=-cd:;-:"ff:i:~:-:-oo::::;,",;---r--:ilJ=.s;::ca=::;cd--:~=iid;::F"-;:;-a·:\J:;-ru=~:;---'--=ilJ:;-:-.s~-r--:m::;...,::;EfO":"H::;:1":;-.--:a:t~j"·.F.~~::".""·"~tljli~";t;~r~"~Kf,nri1'Ja'I1~·-r~c-:~~-=a:iJL~::;:Cll=:d:;::O:---'-::::;ilJ::-:;5:;:ca=d;:;d:-r--ilJ=;5:;-:-ri;-;-~·id--'---il;i-:-oe>-----. ;Go. '<llruii3~ ~ v'~dI:iO ~;Gru "ffeoSO l!f~drt l!fJJlrMt).J rnl'l~~e t!>q1iJel r..hlJd ;5OJiidOJ .o~~C8F" .gill" mol:l~9dOrl ;Gom~ ilJ.scad 'l.3.~e. Clloddri"doJ.lf'/ ~~a;!rcle t!>rpiJel ecrl:rnca;G ri~~M 'OI~0ctq., vel". !wo.l.wort ~~a;!rcle dewao riO"i, nd~M~ ~d 2 3 4 6 7 8 ." 9 10 <\:ldctOa3 Od~~d dc:J~~ iDdd", c:JJ~ 20 121 40 -!.~e. c:JQC><\:l<ti'flc;l, 'l.3.~e. <\:ldctOa3Od~~d 2 20 c:JJeE30rf iDdd", '1'llM idom~ 2, ;50eTlo ~~v'v 400 50 -!.~e. eroc;lc:J~1T.l~Od5 5Qe5, 'l.3.~e. 11iJiI~F" <35ei5d 3 dc:J~~ iDdd", c:JJ~ 20 '1'llM ;do&t~ 3, Tl.r.liidoJ~~v'v 278 80 -!.~e. c:JQC><\:l<ti'flc;l, 5J;)c;l 'l.3.~~. ili.r.JC8< 4 o.>~5> 5Qe5 c:JJeE3orf 20 e;reM ;dom~ 4, v'ri.Jadv ~~u'v 848 40 -!.~e. iDdd", c:JJ~ c:JQC><\:leifelc;l, 'l.3.~e. e5.r.lC8F" E3.i').d~ 5d.JddJ 5 20 c:JJeE3orf iDdd", c:JJ~ e;reM ;do&t~ 5, ~e)orleO ~~v'v 133 60 -!.~e. -

Legend Malaluru Talluru

Village Map of Shivamogga District, Karnataka µ Bilagalikoppa Binkavalli Bilagale Alahalli Devara HosakoppaShankarikoppa Arathalagadde Shakunahalli Sabara Soornagi Shanthapura Yadamata Thuyilakoppa Thoravandha Kodikoppa Bommarasikoppa Talagadde Forest Mallasamudra Moodidoddikoppa Dwarahalli Agasanahalli Kamaruru Thalagundli Madhapura T. Mooguru Ujjanipura JADE Mallapura Kallukoppa Neerlagi Kodihalli MangapuraThelagadde Kachavi Shanuvalli Lakkavalli Vitalapura Mayikoppa Hurulikoppa Jade Devasthana Hakkalu Jigarikoppa Hurali Hurali Bennegere Halekoppa Salagi Bankasana Hirechavati Jigarikoppa ANAVATTI Kubaturu Koppadahalu Bennuru Anavatti Chikkachavati Yammiganura Kaligeri Hanaji Hosakoppa Hosahalli Kodikoppa Chagaturu EnnikoppaEnnikoppa Barangi Yalivala VardhikoppaThumarikoppa Samanavalli Kamanavalli Kotekoppa Thalluru Belavanthanakoppa Jogihalli Kathavalli Ennikoppa Kenchikoppa Kunitheppa Haralakoppa Ennikoppa Iduru Hunasavalli Gummanahalu Badanakatte Kerehalli Siddihalli Haralikoppa Siddihalli Hanche Hirekaligodu Chikkayedagodu Thyavaratheppa Ginivala Basuru Shiddehalli Plantation Hasavi Thudaneeru Hireyadagodu Vrutthikoppa Chikkalagodu Thelagundli Puttanahalli Thalaguppa Kathuru Nellikoppa Jaddihalli Mathighatta Mangarasikoppa Hiremagadi Chikkamagadi Hunasekoppa Bettadakurli Forest Harishi Dyavanahalli Nittakki Negavadi Inam Agrahara Muchhadi Mallenahalli Kamaruru Gendla Bettadakurli Gangavalli Kuntagalale Sindli Sampagodu Thatthuru Haya Bandalike Mutthahalli Kolaga Shankrikoppa Bommenahalli Kanthanahalli Yalagere Malavalli Mangalore -

MARILYN S. THOMPSON Professor T

MARILYN S. THOMPSON Professor T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Arizona State University, Box 873701 Tempe, AZ 85287-3701 Phone: (480) 727-6924 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 1999 Ph.D., University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas Major: Educational Psychology & Research - Quantitative Research Methodology Minor: Psychology - Psychometrics 1996 M.A., University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas Major: Curriculum & Instruction - Science Education 1989 B.A., Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota Major: Chemistry, cum laude Urban Education Program: Semester of studying urban education in Chicago, IL Teaching internship: Whitney Young High School, Chicago Public Schools PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 2020–present Professor, T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics 2019 – 2020 Professor and Interim Director, T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics 2015 – 2019 Professor and Associate Director, T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics 2010 – 2015 Associate Professor, T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics 2012 – 2014 Affiliated Researcher, Learning Sciences Institute 2011 – present Affiliated Faculty, School of Public Affairs 2006 – 2010 Associate Professor, Mary Lou Fulton Institute & Graduate School of Education (2008 – 2010); Mary Lou Fulton College of Education (2006 – 2008); Measurement, Statistics, and Methodological Studies concentration 2008 Visiting Professor at University of Barcelona during -

NINASAM TIRUGATA: Report 2012-13

NINASAM TIRUGATA: Report 2012-13 Vigada Vikramaraya: Tirugata 2012-13: Dir. by Manju Kodagu Mukkam Post Bombilwadi: Tirugata 2012-13: Dir. by Omkar K.R. 1 | P a g e Mukkam Post Bombilwadi: Tirugata 2012-13: Dir. by Omkar K.R. NINASAM TIRUGATA: Tirugata, the itinerant theatre repertory was established in 1985. Ninasam's idea of experimenting with such a project originated in the context of the decline of the professional theatre, and the limited achievements of the amateur theatre in post-independence Karnataka. It also aimed at testing whether it was possible to supplement the overall theatre activity in the state by presenting at a wide variety of centres, productions that combined the best elements of both professional and the amateur movements. It also provided the alumni of the Ninasam Theatre Institute a platform to test their innate talents and imbibed skills. A vast network of friends and contacts made it easier to organise the tour schedules. Trained actors and technicians appointed full time and paid; rehearsals and preparations for about three months; then, a long tour of about four months, encountering varied audiences all over Karnataka -- this, on broad lines, is Tirugata. Tirugata has every year taken three major productions of renowned classics and one children's play to centres with the minimum facilities of a 30ft. x 20 ft. stage area, power supply and accessibility by road. Financing itself almost totally independently, on gate collections, the repertory has had a predominantly rural and semi-rural audience. Most importantly it has firmly proved Ninasam's belief that such a project can take birth and continue to live, nurtured by mass support. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Chandan Gowda

CURRICULUM VITAE Chandan Gowda ADDRESS Azim Premji University (Tel) 91-80-66145100 PESSE Campus, Electronics City (Fax) 91-80-66145103 Hosur Road Email: [email protected] Bengaluru – 560100 [email protected] PRESENT POSITION 2011 – Present Professor of Sociology, Azim Premji University, Bengaluru 2008 – 2011 Associate Professor of Sociology, National Law School of India, Bengaluru EDUCATION 2007 PhD, Sociology, University of Michigan 1998 PhD Certificate, Cultural Studies, University of Pittsburgh 1996 MA, Sociology, University of Hyderabad 1994 BA, Social Science, St. Joseph’s College, Bengaluru 1993 Diploma, French, Alliance Francaise, Bengaluru DISSERTATION Title Development, Elite Agency and the Politics of Recognition in Mysore State, 1881-1947 Committee Jeffery Paige (co-chair), George Steinmetz (co-chair), Sumathi Ramaswamy, Margaret Somers, Julia Adams (Yale University) 1 HONOURS AND AWARDS Visiting Fellow, Watson Institute for International Studies, Brown University, USA, March-May 2015. Schomburg Fellow, Ramapo College, USA, October 2013. Dissertation Research Grant, National Science Foundation, 2003-2004 Rackham Predoctoral Fellowship, University of Michigan, 2002-2003 Dissertation Fieldwork Fellowship, American Institute of Indian Studies, 2002-2003 International Predissertation Research Award, International Institute, University of Michigan, 1999 Regent’s Fellowship, University of Michigan, 1998-1999 Junior Research Fellowship, University Grants Commission, 1996. Gold Medal, MA Sociology, University of Hyderabad, 1996 AREAS OF RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTEREST Social Theory; Cultural Sociology; History of Development Thought; South Asian History and Culture; Caste; Indian Normative Traditions; and Kannada Literature and Cinema PUBLICATIONS Books A Life in the World: UR Ananthamurthy in conversation with Chandan Gowda (Harper Collins-India, October, 2019). Editor, Sahitya Sahavasa (Lectures by UR Ananthamurthy), Shimoga: Aharnishi Prakashana (Forthcoming, August 2019). -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

April-June 2009 No

India Foundation for the Arts Quarterly Newsletter, April-June 2009 No. 12 Recent Projects New Grants Filmmaker-photographer-painter KM Madhusudhanan, performer Jyoti Dogra, and filmmaker Vaibhav Abnave are recipients of recent grants under our Extending Arts Practice programme, which supports artists whose projects emerge from reflections on the larger contexts of their practice. KM Madhusudhan is making a 16mm fictional film on the Indian magic lantern or Shambharik Kharolika, a late 19th century innovation involving the use of painted images on glass to create cinema projections. Through his work, Madhusudhanan has consistently sought to highlight the forgotten continuities between painting, photography, and cinema and its precursors. In making this film, he is both drawing attention to a forgotten technique and reminding us about the overlaps between what are often considered distinct visual genres. Film, television and theatre actor, Jyoti Dogra created The Doorway, an exploration of real and imagined stories in the tradition of Grotowski’s Theatre Laboratory. Jyoti’s performance was a response to current theatre practice which, she says, is “either a coldly intellectual activity, at Meanwhile, filmmaker Vaibhav Abnave is exploring the history one extreme, or else a spectacle, at the other.” By using of experimentation in Marathi theatre with special reference to gestures, mumblings, sounds, and body images, she playwright Mahesh Elkunchwar. He is interested in how sought “to cultivate more intuitive acts of understanding experimentation itself can create orthodoxies and how [in theatre].” Elkunchwar consistently challenged these. Vaibhav’s film will itself challenge the ‘real’ by merging enacted scenes from The Doorway premiered in May at Gallerie Beyond in Elkunchwar’s plays with depictions of the playwright’s inner Mumbai.