Restrictions on Business Structures and Direct Access in the Scottish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Career at the Commercial Bar “…A Career Like No Other with Opportunities Like No Other …”

A CAREER AT THE COMMERCIAL BAR “…a career like no other with opportunities like no other …” 2 A CAREER AT THE COMMERCIAL BAR What is the Commercial Bar? 5 Why should you choose a career 6 at the Commercial Bar? Myths about the Commercial Bar 8 How to qualify as a barrister at the 12 Commercial Bar Useful websites 19 3 “…the front line of advocacy …” 4 WHAT IS THE COMMERCIAL BAR? he independent Bar is a law in which commercial issues arise, specialist referral profession including public law, professional Toffering expert legal advice and negligence, intellectual property, advocacy. Barristers practising at media and entertainment law and the independent Bar are self- construction. Individuals may employed but (in most cases) group specialise in particular areas within together into sets of chambers for the broad field of commercial law, and the purpose of sharing premises and specialism tends to increase other overheads. with seniority. As the law has become more complex, members of the Bar have ‘Commercial law is perhaps tended to specialise in particular areas and to form Specialist Bar best summed up as the law Associations (SBAs), of which COMBAR which applies to business is one. COMBAR now has over 1,200 members with 36 member sets of and financial disputes.’ chambers and individual members from 21 sets across London, Liverpool, Commercial barristers are usually Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol instructed by solicitors rather than and Devon. by a client directly; the services they provide fall into two main areas. First, The members of COMBAR practise and most importantly, a barrister commercial law, which is a broad is a specialist advocate who will term encompassing a wide range of present the client’s case in court. -

Statement of Standards for Solicitor Advocates – Performance Indicators

Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980 section 25A (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1980/46) Rights of Audience in the Court of Session, the High Court of Justiciary, the Supreme Court and Judicial Committee of the Privy Council Statutory requirements: 1) Completion to the satisfaction of the Council of a course of training in evidence and pleading in relation to proceedings in the Courts to which rights of audience are sought 2) Has such knowledge as appears to the Council to be appropriate of (1) the practice and procedure of and (2) professional conduct in regard to those Courts 3) That the Council is satisfied that the applicant is, having regard among other things to the applicant’s experience in appropriate proceedings in the sheriff court, otherwise a fit and proper person to have a right of audience in those Courts Rules C4:1 Rights of Audience in the Civil Courts (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules- and-guidance/section-c-specialities/rule-c4-solicitor-advocates/rules/c41-rights-of- audience-in-the-civil-courts/), C4:2 Rights of Audience in the Criminal Courts (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules-and-guidance/section-c-specialities/rule-c4-solicitor- advocates/rules/c42-rights-of-audience-in-the-criminal-courts/), C4:3 Order of Precedence, Instructions (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules-and-guidance/section-c- specialities/rule-c4-solicitor-advocates/rules/c43-order-of-precedence,-instructions- and-representation/), and Representation and C4:4 Conduct of Solicitor Advocates (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules-and-guidance/section-c-specialities/rule-c4-solicitor- advocates/rules/c44-conduct-of-solicitor-advocates/) apply. -

Practice Direction 23 Court Applications

Practice Direction 23 Court Applications Date Issued: 21 June 2013 Date Implemented: 24 June 2013 Date Last Revised: 26 January 2015 SUMMARY Role of Reporters and General Principles Reporters are to: • promote the general principles in relation to the welfare of the child being paramount, views of the child and minimum intervention as they apply to court applications1, • be fair, knowledgeable and proficient in relation to relevant statutory provisions and court procedures, and • in proof applications make all reasonable efforts to bring about a prompt decision in relation to the application. Process of proof applications A proof application must be made within 7 days of the grounds hearing. The court rules set out the form of application. A proof application must be heard within 28 days of being lodged. Jurisdiction of proof applications An application in relation to offence grounds must be made to the sheriff who would have jurisdiction if the child were being prosecuted for the offence. For non-offence grounds, the application must be made to the sheriff court district where the child is habitually resident. On cause shown, the sheriff may remit any application to another sheriff court. Service, attendance and representation in proof applications The sheriff may dispense with (i) service of all or part of the application on the child, and (ii) the attendance of the child. Reporters must include information on dispensing with service and attendance in the application (if applicable). On receipt of the warrant to cite, the reporter must forthwith serve this and a copy of the application on the child (unless service has been dispensed with), each relevant person and any safeguarder. -

Annual Report 2016–2017

Annual Report 2016–2017 Annual Report 2016–2017 Published pursuant to section 18 of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers SG/2017/132 © Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland (JABS) copyright 2017 The text in this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as JABS copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland Thistle House 91 Haymarket Terrace Edinburgh EH12 5HD E-mail: [email protected] This publication is only available on our website at www.judicialappointments.scot Published by the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland, September 2017 Designed in the UK by LBD Creative Ltd Annual Report 2016–2017 Contents Our aims ii Foreword 1 Introduction and Membership 3 Committees and Groups 6 Diversity 11 Appointment Rounds 12 Meetings and Outreach 20 Tribunals 21 Complaints 22 Freedom of Information 23 Secretariat 24 Website 25 Financial Statement 26 Annex 1: Board Members and Lay Selection Panel Members 27 Annex 2: Board Member Attendance 33 i i JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS BOARD FOR SCOTLAND Our aims are: To attract applicants of the highest calibre, to encourage diversity in the range of those available for selection, and to recommend applicants for appointment to judicial office on merit through processes that are fair, transparent and command respect. -

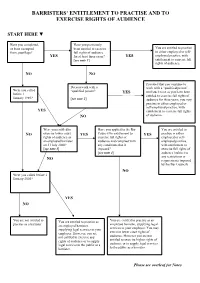

Barristers' Entitlement to Practise and to Exercise

BARRISTERS’ ENTITLEMENT TO PRACTISE AND TO EXERCISE RIGHTS OF AUDIENCE START HERE ▼ Have you completed, Have you previously or been exempted been entitled to exercise You are entitled to practise in either employed or self- from, pupillage? full rights of audience YES for at least three years? YES employed practice, with [see note 1] entitlement to exercise full rights of audience. NO NO Provided that you continue to Do you work with a work with a “qualified person” Were you called “qualified person? YES until such time as you have been before 1 entitled to exercise full rights of January 1989? [see note 2] audience for three years, you may practise in either employed or self-employed practice, with YES entitlement to exercise full rights NO of audience. Were you entitled to Have you applied to the Bar You are entitled to NO exercise lower court YES Council for entitlement to YES practise in either rights of audience as exercise full rights of employed or self- an employed barrister audience and complied with employed practice, on 31 July 2000? any conditions that it with entitlement to [see note 3] imposed? exercise full rights of [see note 4] audience (subject to any restrictions or NO requirements imposed by the Bar Council). NO Were you called before 1 January 2002? YES NO You are not entitled to You are entitled to practise as You are entitled to practise as an practise as a barrister an employed barrister, employed barrister, supplying legal supplying legal services to your services to your employer. You may employer. -

Adam Mckinlay

Advocates Library, Parliament House, Edinburgh, EH1 1RF Telephone: 0131 226 2881 Facsimile : 0131 225 3642 DX ED 549302, Edinburgh 36, LP3 Edinburgh 10 Adam McKinlay Year of Call: 2018 [email protected] 07753 267455 Professional Career to date Devil Masters: Chris Paterson, Dan Byrne, Sarah Livingstone 2017-2018: Devil, Faculty of Advocates 2015-2017: Solicitor Advocate & Associate, Brodies LLP 2012-2015: Senior Solicitor, Brodies LLP 2010-2012: Solicitor, Brodies LLP 2008-2010: Trainee, Brodies LLP Education & Professional Qualifications Lord Reid Scholarship, Faculty of Advocates (2017-2018) Chartered Insurance Institute, Diploma in Insurance (2014) Diploma in Legal Practice, University of Edinburgh (2008) LLB (Hons) (First Class), University of Edinburgh (2007) Academic Prizes: Lord President Cooper Memorial Prize (2007) – Honours Student of Outstanding Distinction John Hastie Scholarship (2007) – best performance in Ordinary courses by an LLB graduate Miller Prize (2005) – class prize for Commercial Law Tods Murray Scholarship (2005) – combined prize for Commercial and Property Law James Craig Howie Memorial Prize (2005) – combined prize for private law subjects McGrigors Prize (2005) – combined prize for Commercial Law, Property and Taxation Margaret Balfour Keith Prize (2004) – class prize for Public Law Thow Scholarship (2004) – class prize for Obligations Areas of Expertise Professional Liability Construction and Engineering Commercial Contracts Commercial Property Public Law, Judicial Review and Human Rights Alternative Dispute Resolution Professional Experience Adam called to the Bar in 2018 as the Lord Reid Scholar 2017-18. Adam’s areas of practice are commercial and public law. He has a particular expertise in professional negligence actions. He also regularly acts for clients in construction, property and contractual disputes and has significant experience of obtaining interim orders. -

Civil Courts Online Survey Summary- Analysis of Research April 2021

Law Society of Scotland Civil Courts Online Survey Summary- Analysis of Research April 2021 Introduction The Law Society of Scotland is the professional body for over 12,000 practising Scottish solicitors. We are a regulator that sets and enforces standards for the solicitor profession which helps people in need and supports business in Scotland, the UK and overseas. We support solicitors and drive change to ensure Scotland has a strong, successful and diverse legal profession. We represent our members and wider society when speaking out on human rights and the rule of law. We also seek to influence changes to legislation and the operation of our justice system as part of our work towards a fairer and more just society. The coronavirus pandemic continues to affect each and every one of us. Over the last year we have had to adapt both our working and our personal lives in order to minimise the spread of infection and save lives. While there appears at present to be some progress with regard to easing of current restrictions, we will all be required to adapt our daily lives for the foreseeable future. This research is the latest in a number of Covid-19 related reports by the Society since the outbreak of the pandemic which have been undertaken to gain a better understanding of the impact coronavirus has had on the profession. It is anticipated that this research into remote civil court procedures and the use of technology in remote civil courts will help inform discussions with key stakeholders such as Scottish Government, Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS) and Scottish Legal Aid Board (SLAB) as to how civil courts can better operate during the pandemic. -

Guide to Professional Conduct

FACULTY OF ADVOCATEADVOCATESSSS GUIDE TO THE PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT OF ADVOCATEADVOCATESSSS Published by the Faculty of Advocates, Parliament House, Edinburgh First Published June 1988 Second Edition January 2005 Third Edition June 2006 Fourth Edition August 2007 Fifth Edition October 2008 CONTENTS Chapter Introduction Note 1. The Status, Rights and Obligations of an Advocate 2. The General Principles of Professional Conduct 3. Duties in Relation to the Faculty and other Advocates 4. Duties in Relation to the Instructing Agent 5. Duties in Relation to the Client 6. Duty to the Court and Duties Connected with Court and Similar Proceedings 7. Duty to Seek Advice 8. Instructions 9. Fees 10. Advertising, Publicity, Touting and Relations with the Media 11. Discipline 12. Dress 13. Duties of Devilmaster 14. Continuing Professional Development 15. Discrimination 16. Non Professional Activities of Practising Advocate 17. Advocates Holding a Public Office and Non-practising Advocates 18 . Work Outside Scotland 19. European Lawyers Appearing in Scotland 20. Registered European Lawyers 21. Precedence of Counsel of Other Bars 22. Proceeds of Crime Act 2 Appendices Appendix A The Declaration of Perugia Appendix B Code of Conduct for European Lawyers produced by the CCBE Appendix C Faculty of Advocates Continuous Professional Development Regulations Appendix D Direct Access Rules and associated documents Appendix E Guidance in relation to Proceeds of Crime and Money Laundering 3 INTRODUCTION The work of an Advocate is essentially the work of an individual practitioner whose conscience, guided by the advice of his seniors, is more likely to tell him how to behave than any book of rules. In places in this Guide, it has been found convenient to state "the rule" or "the general rule". -

Practice Notes for Safeguarders on Court

PRACTICE NOTES FOR SAFEGUARDERS ON COURT Part I PRACTICE POSITIONS including statements of practice expected from Safeguarders. Part II INFORMATION including relevant law, structures and roles relevant to court. Part III PRACTICE including step-by-step process and potential contributions. January 2019 PRACTICE NOTE FOR SAFEGUARDERS ON COURT FOREWORD Court proceedings are involved in the Children’s Hearings System to allow challenge to grounds or decisions that justify compulsory intervention in a child and a family’s life. The court is a different context to that of a Children’s Hearing. There is often a lot at stake for children and their families and it can be difficult to understand and participate in what are more formal processes. The Safeguarder has an important role to play in keeping the child at the centre and safeguarding the interests of the child during the child’s involvement in this part of the hearings system. The Safeguarder is the only role tasked exclusively with this focus. It is important that Safeguarders are able to perform their role to the highest of standards and in doing so, never lose sight of the individual child and their needs whilst these proceedings are ongoing. Practice Notes supplement the Practice Standards for Safeguarders by providing further clarity on the expectations of Safeguarder practice and conduct. 2 PRACTICE NOTE FOR SAFEGUARDERS ON COURT Contents PRACTICE NOTE ON COURT – PART I - PRACTICE POSITIONS ............................................................. 6 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... -

Litigants in Person

Litigants in Person Litigants in Person Key points The ‘litigant in person’ In March 2013 the Master of the Rolls issued a Practice Guidance1 which determined that the term ‘Litigant in Person’ should continue to be the sole term used to describe individuals who exercise their right to conduct legal proceedings on their own behalf. The Practice Guidance applies to all proceedings in all criminal, civil and family courts (though not curiously to tribunal proceedings), For the purposes of clarity, the term ‘litigant in person’ (as opposed to ‘self‐represented litigant’ or ‘unrepresented party’) is used in this chapter in line with the Practice Guidance both to those appearing unrepresented in courts and also in tribunals. The term encompasses those preparing a case for trial or hearing, those conducting their own case at a trial or hearing and those wishing to enforce a judgment or to appeal. Most litigants in person are stressed and worried, operating in an alien environment in what for them is a foreign language. They are trying to grasp concepts of law and procedure about which they may be totally ignorant. They may well be experiencing feelings of fear, ignorance, frustration, bewilderment and disadvantage, especially if appearing against a represented party. The outcome of the case may have a profound effect and long‐term consequences upon their life. They may have agonised over whether the case was worth the risk to their health and finances, and therefore feel passionately about their situation. Role of the judge Judges must be aware of the feelings and difficulties experienced by litigants in person and be ready and able to help them, especially if a represented party is being oppressive or aggressive. -

Solicitors' Rights of Audience, Competence and Regulation: A

Legal Studies (2021), 1–18 doi:10.1017/lst.2021.5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Solicitors’ rights of audience, competence and regulation: a responsibility rights approach Jane Ching* Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK *Author e-mail: [email protected] (Accepted 22 December 2020) Abstract This paper takes as its context the decision of the Solicitors Regulation Authority in England and Wales to abandon before the event regulation of lower court trial advocacy. Although solicitors will continue to acquire rights of audience on qualification, they will no longer be required to undertake training or assessment in witness examination, by contrast with other, competing, legal professions. Their opportunities to acquire competence outside the classroom will remain limited. The paper first explores this context and its implica- tions for the three key factors of rights to perform, competence and regulatory accountability. The current regulatory system is then displayed as a Hohfeldian network of rights and duties held in tension between sta- keholders intended to inhibit the incompetent exercise of rights to conduct trial advocacy. The SRA’s proposal weakens this tension field and threatens the competitive position of solicitors. The paper therefore finally offers a radical alternative reconceptualisation of rights of audience in terms of Waldron’s ‘responsibility rights’ as a solution, albeit one with significant implications for the individual advocate. This model, applic- able globally, is closer to notions of societal good and professionalism than to those of the competitive market, whilst inhibiting incompetent performance and remediating the SRA’s approach. Keywords: trial advocacy; practice; procedure and ethics; legal regulation; legal education Introduction The legal services market in England and Wales possesses two peculiarities. -

'Where's Kilbrandon Now?': Reviewing Child Justice in Scotland

'Where's Kilbrandon Now?': reviewing child justice in Scotland Maggie Mellon reports on 'Where's Kilbrandon Now?', the inquiry into the future of the Scottish children's hearing system. Child Justice in Scotland is based on a system of hearings have been somewhat wrapped in cotton hearings held by panels .It was established in 1968, wool. The protective instincts of the various 'keepers' in response to a report by Lord Kilbrandon, a senior of the system, (18 years of which were under Scottish laws lord. In recent years the hearings Conservative governments) have indeed preserved system has come under criticism for being 'too soft', the system, but at a cost. There was very little and there have been calls to take child justice back evaluation of what actually happened at hearings, and to the courts. how and why decisions were made. Did children and young people and their families feel consulted? Was ut dated? Too soft? Over-burdened? Under- there clarity about rights and responsibilities? resourced? These were some of the There was even less evaluation of outcomes - Oquestions that NCH Scotland posed in our what happens during home supervision orders? What inquiry into the future of the children's hearings happens to children taken away from home on system in post-devolution Scotland. residential supervision orders? Is secure care The hearings system, established 30 years ago necessary for all the children who are authorised for in the wake of the Kilbrandon report, reflected a this extreme measure? Why do so many young men forward-looking and confident civic Scotland, go straight from the hearing system to the adult courts willing and able to take a radical and informed and then often straight to jail at the age of only 16 or approach to 'delinquent' and deprived children and 17? young people.