Kristen Clanton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 30 2018 Seminole Tribune

BC cattle steer into Brooke Simpson relives time Heritage’s Stubbs sisters the past on “The Voice” win state title COMMUNITY v 7A Arts & Entertainment v 4B SPORTS v 1C Volume XLII • Number 3 March 30, 2018 National Folk Museum 7,000-year-old of Korea researches burial site found Seminole dolls in Manasota Key BY LI COHEN Duggins said. Copy Editor Paul Backhouse, director of the Ah-Tah- Thi-Ki Museum, found out about the site about six months ago. He said that nobody BY LI COHEN About two years ago, a diver looking for Copy Editor expected such historical artifacts to turn up in shark teeth bit off a little more than he could the Gulf of Mexico and he, along with many chew in Manasota Key. About a quarter-mile others, were surprised by the discovery. HOLLYWOOD — An honored Native off the key, local diver Joshua Frank found a “We have not had a situation where American tradition is moving beyond the human jaw. there’s organic material present in underwater horizon of the U.S. On March 14, a team of After eventually realizing that he had context in the Gulf of Mexico,” Backhouse researchers from the National Folk Museum a skeletal centerpiece sitting on his kitchen said. “Having 7,000-year-old organic material of Korea visited the Hollywood Reservation table, Frank notified the Florida Bureau of surviving in salt water is very surprising and to learn about the history and culture Archaeological Research. From analyzing that surprise turned to concern because our surrounding Seminole dolls. -

Wild’ Evaluation Between 6 and 9Years of Age

FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:05 PM Residential&Commercial Sales and Rentals tvspotlight Vadala Real Proudly Serving Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Cape Ann Since 1975 Estate • For the week of July 11 - 17, 2015 • 1 x 3” Massachusetts Certified Appraisers 978-281-1111 VadalaRealEstate.com 9-DDr. OsmanBabsonRd. Into the Gloucester,MA PEDIATRIC ORTHODONTICS Pediatric Orthodontics.Orthodontic care formanychildren can be made easier if the patient starts fortheir first orthodontic ‘Wild’ evaluation between 6 and 9years of age. Some complicated skeletal and dental problems can be treated much more efficiently if treated early. Early dental intervention including dental sealants,topical fluoride application, and minor restorativetreatment is much more beneficial to patients in the 2-6age level. Parents: Please makesure your child gets to the dentist at an early age (1-2 years of age) and makesure an orthodontic evaluation is done before age 9. Bear Grylls hosts Complimentarysecond opinion foryour “Running Wild with child: CallDr.our officeJ.H.978-283-9020 Ahlin Most Bear Grylls” insurance plans 1accepted. x 4” CREATING HAPPINESS ONE SMILE AT ATIME •Dental Bleaching included forall orthodontic & cosmetic dental patients. •100% reduction in all orthodontic fees for families with aparent serving in acombat zone. Call Jane: 978-283-9020 foracomplimentaryorthodontic consultation or 2nd opinion J.H. Ahlin, DDS •One EssexAvenue Intersection of Routes 127 and 133 Gloucester,MA01930 www.gloucesterorthodontics.com Let ABCkeep you safe at home this Summer Home Healthcare® ABC Home Healthland Profess2 x 3"ionals Local family-owned home care agency specializing in elderly and chronic care 978-281-1001 www.abchhp.com FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:06 PM 2 • Gloucester Daily Times • July 11 - 17, 2015 Adventure awaits Eight celebrities join Bear Grylls for the adventure of a lifetime By Jacqueline Spendlove TV Media f you’ve ever been camping, you know there’s more to the Ifun of it than getting out of the city and spending a few days surrounded by nature. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

Doll Collecting; a Course Designed for the Adult Education Student. PUB DATE Jul 74 NOTE 145P.; Ed.D

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 099 543 CE 002 628 AUTHOR Berger, Betty M. TITLE Doll Collecting; A Course Designed for the Adult Education Student. PUB DATE Jul 74 NOTE 145p.; Ed.D. Dissertation, Walden University EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$6.60 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Adult Education; *Course Content; Course Descriptions; *Doctoral Theses; Teacher Developed Materials; *Teaching Techniques IDENTIFIERS *Doll Collecting ABSTRACT The author has attempted to organize the many materials to be found on doll collecting into a course which will provide a foundation of know]edge for appreciating and evaluating old dolls. The course has been divided into sessions in which old dolls will be studied by type (images, idols, and early playthings; child, doll, and social realities; wooden dolls; wax dolls; papier mache and composition; china and parian; bisque dolls, cloth dolls; celluloid, metal, leather, and rubber dolls; and doll art in America) in basically the same chronological order in which they achieved popularity in the marketplace (1800-1925). The instructor is urged to employ a variety of teaching strategies in the presentation of the material. A mixture of lecture, slides, show and tell, and much student participation is encouraged. Handouts are provided whichcan be given to students at the end of each session. Brief annotated bibliographies appear at the end of each chapter,as well as a selected bibliography at the end of the course. Thecourse has been designed to introduce the beginning doll collector to the techniques employed in the manufacture of old dolls, to help the novice identify a doll of excellent artistic merit, and to acquaint the collector with some of the better known names in doll making. -

Galatea's Daughters: Dolls, Female Identity and the Material Imagination

Galatea‘s Daughters: Dolls, Female Identity and the Material Imagination in Victorian Literature and Culture Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Maria Eugenia Gonzalez-Posse, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: David G. Riede, Advisor Jill Galvan Clare A. Simmons Copyright by Maria Eugenia Gonzalez-Posse 2012 Abstract The doll, as we conceive of it today, is the product of a Victorian cultural phenomenon. It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that a dedicated doll industry was developed and that dolls began to find their way into children‘s literature, the rhetoric of femininity, periodical publications and canonical texts. Surprisingly, the Victorian fascination with the doll has largely gone unexamined and critics and readers have tended to dismiss dolls as mere agents of female acculturation. Guided by the recent material turn in Victorian studies and drawing extensively from texts only recently made available through digitization projects and periodical databases, my dissertation seeks to provide a richer account of the way this most fraught and symbolic of objects figured in the lives and imaginations of the Victorians. By studying the treatment of dolls in canonical literature alongside hitherto neglected texts and genres and framing these readings in their larger cultural contexts, the doll emerges not as a symbol of female passivity but as an object celebrated for its remarkable imaginative potential. The doll, I argue, is therefore best understood as a descendant of Galatea – as a woman turned object, but also as an object that Victorians constantly and variously brought to life through the imagination. -

THE MEDDLER by Lorene Scafaria April 1, 2015

THE MEDDLER by Lorene Scafaria April 1, 2015 FADE IN: A ceiling fan spinning slow and sad above us. 1 INT. APARTMENT - BEDROOM -- MORNING 1 MARNIE MINERVINI (60s) stares at the ceiling, tucked in her side of the bed, a chasm of empty space beside her. She sighs, forgotten. Then turns to the window. Looks out at the California sun. And immediately brightens. She props herself up and out of bed. MARNIE (V.O.) Anyway... Her chipper Brooklyn/Jersey accent rings out: 2 INT. WEST HOLLYWOOD - APPLE STORE -- DAY 2 Marnie makes her way through the store, happy and confused. MARNIE (V.O.) Today I went across the street to the Apple store and got one of the new iPhones with the 64 gigabytes cause I wasn’t sure if I should get the 16s or the 64s but the 64s looked good so there you go. 3 EXT. THE GROVE -- LATER 3 Marnie has breakfast with her iPhone. MARNIE (V.O.) The genius bartender showed me how to make things bigger but I already forgot. God, my eyesight is so shot. But I got on the Safari before and I looked up The Palazzo and it said they filmed “The Hills” here for two seasons. Isn’t that neat? -- Marnie happily weaves through The Grove’s morning crowd. MARNIE (V.O.) And they used to do the Extra program at The Grove every day with Mario Lopez. He seems nice. 2. -- Marnie stands shyly at the fountain, watching the children play nearby. MARNIE (V.O.) I swear I could stand there and watch that fountain for hours. -

How Twin Peaks Changed the Face of Contemporary Television

“That Show You Like Might Be Coming Back in Style” 44 DOI: 10.1515/abcsj-2015-0003 “That Show You Like Might Be Coming Back in Style”: How Twin Peaks Changed the Face of Contemporary Television RALUCA MOLDOVAN Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca Abstract The present study revisits one of American television’s most famous and influential shows, Twin Peaks, which ran on ABC between 1990 and 1991. Its unique visual style, its haunting music, the idiosyncratic characters and the mix of mythical and supernatural elements made it the most talked-about TV series of the 1990s and generated numerous parodies and imitations. Twin Peaks was the brainchild of America’s probably least mainstream director, David Lynch, and Mark Frost, who was known to television audiences as one of the scriptwriters of the highly popular detective series Hill Street Blues. When Twin Peaks ended in 1991, the show’s severely diminished audience were left with one of most puzzling cliffhangers ever seen on television, but the announcement made by Lynch and Frost in October 2014, that the show would return with nine fresh episodes premiering on Showtime in 2016, quickly went viral and revived interest in Twin Peaks’ distinctive world. In what follows, I intend to discuss the reasons why Twin Peaks was considered a highly original work, well ahead of its time, and how much the show was indebted to the legacy of classic American film noir; finally, I advance a few speculations about the possible plotlines the series might explore upon its return to the small screen. Keywords: Twin Peaks, television series, film noir, David Lynch Introduction: the Lynchian universe In October 2014, director David Lynch and scriptwriter Mark Frost announced that Twin Peaks, the cult TV series they had created in 1990, would be returning to primetime television for a limited nine episode run 45 “That Show You Like Might Be Coming Back in Style” broadcast by the cable channel Showtime in 2016. -

Laboratorio Dell'immaginario 30 Anni Di Twin Peaks

laboratorio dell’immaginario issn 1826-6118 rivista elettronica http://archiviocav.unibg.it/elephant_castle 30 ANNI DI TWIN PEAKS a cura di Jacopo Bulgarini d’Elci, Jacques Dürrenmatt settembre 2020 CAV - Centro Arti Visive Università degli Studi di Bergamo LUCA MALAVASI “Do you recognize that house?” Twin Peaks: The Return as a process of image identification In the fourth episode of the new season of Twin Peaks (2017), also known as Twin Peaks: The Return, Bobby Briggs – formerly a young loser and wrangler, and now a deputy at the Twin Peaks Sheriff’s Department – meets Laura Palmer, his high school girlfriend. Her photographic portrait, previously displayed among the trophies and other photos in a cabinet at the local high school they attended (we see it at the beginning of the first episode),1 sits on the table of a meeting room. It had been stored in one of the two containers used to hold the official documents in the investigation into Lau- ra’s murder; like two Pandora’s boxes, these containers have been opened following a statement from the Log: “Something is missing”. That ‘something’ – Margaret Lanterman (‘The Log Lady’) clarifies to deputy Hawk – concerns Agent Cooper and, consequently, his investigation into Laura Palmer’s death. The scene is rather moving, not least because, after four episodes, viewers finally hear the famous and touching Laura Palmer’s theme for the first time.2 As the music starts, we see Bobby’s face, having entered the meeting room where Frank Truman, Tommy Hawks, Lucy, and Andy are gathered. He literally freezes in front of Lau- ra’s framed image, and a ‘dialog’ begin between the two ex-lovers; 1 It’s the same portrait showed at the beginning of the first season, actually the portrait of Laura Palmer. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

V. 81, Issue 19, April 16, 2014

Volume 81, Issue 19 Smithfield, RI April 16, 2014 Inside ‘Change the Voice of One, this Change the Views of Many’ Jarrod Clowery, a Boston Bombing survivor and his foundation - Hero’s Hearts Foundation edition By Hanna Williamson Contributing Writer Where were you on April 15, 2013 at 2:49 pm? Only one short year Business: ago, I vividly remember sitting in Salmanson Dining Hall, with my Iphone 6 preview eyes glued to the breaking news coverage playing on all the TVs. For the first time in my Bryant career, an eerie hush filled the dining hall as everyone around me also stared blankly at the breaking news coverage. The typical “Salmo” chatter was replaced with the frantic news reporters and coverage of the tragic scene happening live on Boylston Street in Boston, Massachusetts. The 2013 Marathon Monday that we all know as a renowned New England tradition, Page 6 turned into a horrific sight, playing out right before our eyes, terrorists had set off two bombs. This past fall semester I participated in the Management-200 Service Learning Project. Through this semester long project, I had the opportunity to work with one inspiring individual and survivor Sports: of the Boston Marathon bombing, Jarrod Clowery. Bulldogs’ softball On April 15th, standing only three feet in front of the second bomb, Jarrod was blown into Bolyston Street, puncturing the back of team deserves his legs with shrapnel and debris emitted recognition See “Hero’s Hearts Foundation,” page 3 Koffler Center outdoor renovations set The Koffler Communication Complex has plans for improvements this summer By May Vickers Page 7 Staff Writer As part of Bryant University’s ongoing sustainability efforts the Facilities Opinion: Department will renovate Lammily takes on the Koffler building with sustainability innovative Boral Barbie TruExterior Trim this coming summer. -

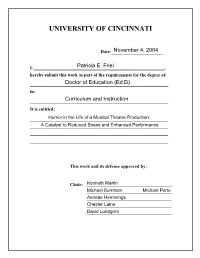

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Humor in the Life of a Musical Theatre Production: A Catalyst to Reduced Stress and Enhanced Performance By Patricia E. Friel M.A., Speech and Communication Arts, University of Cincinnati, December 1979 B.A., Speech and Communication Arts and French Language and Literature, University of Cincinnati, June 1978 A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education (Ed.D) Dissertation Committee Chair: Dr. Kenneth Martin Department of Curriculum and Instruction University of Cincinnati College of Education November, 2004 ABSTRACT Based on an ethnographic exploration of social psychological phenomena within the context of a musical theatre production at a Midwestern University, humor was found to play an integral part in the lives of actors/performers, directors, and stage managers. Major themes that surfaced concentrated on the role of humor in helping student actors/performers (a) cope with situational factors related to stress, tensions, and performance anxieties and/or (b) engage productively in the development -

Printable PDF Version

1 “Call for help”: Analysis of Agent Cooper’s Wounded Masculinity in Twin Peaks 2.6.2021 Dale Cooper Twin Peaks crime fiction detective fiction masculinity trauma Karla Lončar karla.loncar[a]lzmk.hr Ph.D. candidate Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography This essay explores the shifts in representation of the masculinity of FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper, one of the leading characters of the Twin Peaks fictional universe, created by David Lynch and Mark Frost. The research covers three chapters. The first chapter serves as an analysis of Cooper’s character from the original television series (1990–91) and Lynch’s film prequel Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), in which he is interpreted as an intuitive detective (Angela Hague), who departs from the conventional depiction of detective characters. The second one investigates Cooper’s “returns” in the third season/Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) and their significance for his character development through the lens of psychoanalytic interpretations of the detective/crime genre and its connections to past trauma (Sally Rowe Munt). The third chapter further explores the struggles of Cooper’s three major self-images in The Return: the Good Dale/DougieCooper, Mr. C and Richard, all of which suggest certain issues in perception of his masculinity, by referring to several psychoanalytic, feminist and masculinity scholars (Isaac D. Balbus, Jack Halberstam, Lee Stepien), official Twin Peaks novels The Autobiography of F.B.I. Special Agent Dale Cooper: My Life, My Tapes (Scott Frost, 1991) and Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier (Mark Frost, 2017) as well as the Ancient myth of Orpheus and Alfred Hitchcock’s film Vertigo (1958).