Jeffs Complete Portfolio.24183945 (Pdf) Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communications Status Report for Areas Impacted by Hurricane Ida September 8, 2021

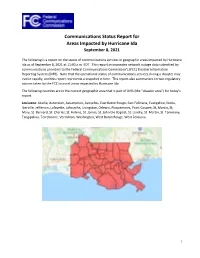

Communications Status Report for Areas Impacted by Hurricane Ida September 8, 2021 The following is a report on the status of communications services in geographic areas impacted by Hurricane Ida as of September 8, 2021 at 11:00 a.m. EDT. This report incorporates network outage data submitted by communications providers to the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Disaster Information Reporting System (DIRS). Note that the operational status of communications services during a disaster may evolve rapidly, and this report represents a snapshot in time. This report also summarizes certain regulatory actions taken by the FCC to assist areas impacted by Hurricane Ida. The following counties are in the current geographic area that is part of DIRS (the “disaster area”) for today’s report. Louisiana: Acadia, Ascension, Assumption, Avoyelles, East Baton Rouge, East Feliciana, Evangeline, Iberia, Iberville, Jefferson, Lafayette, Lafourche, Livingston, Orleans, Plaquemines, Point Coupee, St, Martin, St, Mary, St. Bernard, St. Charles, St. Helena, St. James, St. John the Baptist, St. Landry, St. Martin, St. Tammany, Tangipahoa, Terrebonne, Vermillion, Washington, West Baton Rouge, West Feliciana. 1 911 Services The Public Safety and Homeland Security Bureau (PSHSB) learns the status of each Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) through the filings of 911 Service Providers in DIRS, reporting to the FCC’s Public Safety Support Center, coordination with state 911 Administrators and, if necessary, direct contact with individual PSAPs. Louisiana: No PSAPs are reported as being affected. The following chart shows the trend in the effects on PSAPs since the storm’s landfall: 2 Wireless Services The following section describes the status of wireless communications services and restoration in the disaster area. -

The House That Jack Built

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-20-2005 The House that Jack Built William Loehfelm University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Loehfelm, William, "The House that Jack Built" (2005). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 226. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/226 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE THAT JACK BUILT A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of English by Bill Loehfelm B.A. University of Scranton, 1991 May, 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One .........................................................................................................................1 Chapter Two.......................................................................................................................12 -

Page 1 of 8 Guaranty Broadcasting Company of Baton Rouge, LLC FM

Guaranty Broadcasting Company of Baton Rouge, LLC FM RADIO STATIONS WDGL, WBRP, WNXX, WTGE & KNXX EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2017 – January 31, 2018* I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the Master Recruitment Source List (“MRSL”) for recruitment source data. Recruitment Sources RS Referring Job Title (RS) Used To Fill Hiree Vacancy Sales Executive 1-9,11-14,16-30, 32-43 41 Sales Executive 1-9,11-14,16-30, 32-43 41 Sales Executive 1-9,11-14,16-30, 32-43 41 Sales Executive 1-9,11-14,16-30, 32-43 37 Program Director 2-9, 12-19, 23-26, 29-30, 37 32-44 35 _______________________________________________________________________________________ *This Report includes recruitment data collected from February 1, 2017-January 31, 2018. Page 1 of 8 Guaranty Broadcasting Company of Baton Rouge, LLC FM RADIO STATIONS WDGL, WBRP, WNXX, WTGE & KNXX EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2017 – January 31, 2018* II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST (MRSL) Source No. of RS Entitled To Interviewees RS Information Vacancy Referred by RS Number Notification? Over 12-month (Yes/No) Period 1. Nicholls State University Y 0 P. O. Box 2006 Thibodaux, LA 70313 (985) 446-8111 www.collegecentral.com/nicholls 2. The Advocate, Classified N 1 P.O. Box 588 Baton Rouge, LA 70821 (225) 388-0111 3. Baton Rouge Community College Y 0 5310 Florida Blvd. Baton Rouge, LA 70806 (225) 216-8019 [email protected] 4. Southeastern University Y 0 Career Services Hammond, Louisiana (985) 549-2121 www.selu.edu./career 5. Camelot Career College N 0 2618 Wooddale Blvd. -

Thaiwanda Interactive Epk

THAIWANDA INTERACTIVE EPK *CLICK HERE AWARD WINNING ENTERTAINER PRODUCER > < / / COMPOSER CREATIVE BIOGRAPHY//<> *CLICK HERE A new breed of African Mavrick fueled by a deeply personal quest to elivate African arts and culture, Thaiwanda is a unique seasoned blend of entatertainer, performer and presenter with over 15years in the entertainment business. Armed with a sound and flare that trancends genres; over time he has honed the ability to articulate and integrate African sounds and rhythms into a rich fusion of musical textures and sonics resulting in a fresh Pan-African International Festival sound. From international heavyweights such as DJ Snake (Turn Down For What) playing his music in Las Vegas to working side by side with 3x Grammy Winner Brian Soko (Beyonce & Jay Z - Drunk In Love). Thaiwanda recently made history breaking multiple venue records, as a co-headliner on the #TehnOuttaTenTour a first of its kind 10 city tour across Zimbabwe. Other accoplishments, includes perfoming to a crowd 22000 plus crowd at the Castle Lite Unlocks J Cole held at the Computicket Dome in Johannesburg. He has also opened for acts the likes of Tinnie Tempa, Rick Ross and Ludacris. With an arsenal of anthemic hooks, smoldering melodies and masterful production this budding icon has become a regular fixture on charts across the continent. From major and regional radio stations to topping charts on TRACE, MTV and Channel O. Earning him certified hit maker status and title of “African Titan” as published by Hype Magazine. Thaiwanda over the years has built a solid catalogue of work that comprises of releases that span Africa. -

Detailed Itinerary

TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE Panama Canal Cruise & Panama: A Continent Divided, Oceans United 2020 Small Groups: 20-24 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 22) Overseas Adventure Travel ® Small Ships, Smaller Groups, Undiscovered Ports 1 Overseas Adventure Travel ® 347 Congress Street, Boston, MA 02210 Dear Traveler, For centuries, history's most intrepid explorers have gazed upon the horizon in search of life- changing discoveries. We invite to you to join their ranks—and seek out unforgettable experiences aboard our 16- to 210-passenger small ships, in groups of 20-25 travelers (with an average of 22). In the following pages, you'll find detailed information on this special Small Ship Adventure. We know that you have numerous options available to you as you make your travel plans, but only O.A.T. offers you the most immersive, authentic travel experience. Plus, with the lowest prices in small ship travel, and FREE or low-cost Single Supplements on all of our trips, you won't find a better value—guaranteed. We believe that travel is about immersion—and our small groups and smaller ships are key to making travel dreams a reality. Aboard a member of our award-winning small ship fleet—recently ranked #2 on Travel + Leisure's Top 10 "World's Best" Small Ship Ocean Cruise Lines for 2018—you'll embark on an active exploration of your dream destination with like-minded American travelers who share your passion for discovery. With your small ship's easy access to intimate, off-the-beaten-path destinations, you'll explore the highlights and hidden gems of each port of call—all while gaining even richer insights from the people who know your destination best. -

Dead Zone Back to the Beach I Scored! the 250 Greatest

Volume 10, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television FAN MADE MONSTER! Elfman Goes Wonky Exclusive interview on Charlie and Corpse Bride, too! Dead Zone Klimek and Heil meet Romero Back to the Beach John Williams’ Jaws at 30 I Scored! Confessions of a fi rst-time fi lm composer The 250 Greatest AFI’s Film Score Nominees New Feature: Composer’s Corner PLUS: Dozens of CD & DVD Reviews $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada �������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ���������������������� contents ���������������������� �������� ����� ��������� �������� ������ ���� ���������������������������� ������������������������� ��������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����� ��� ��������� ����������� ���� ������������ ������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ��������������������� �������������������� ���������������������������������������������� ����������� ����������� ���������� �������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ������������������������������� �������������������������� ���������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������� -

MMR 24-7 Song Airplay Detail 5/27/14, 11:45 AM

MMR 24-7 Song Airplay Detail 5/27/14, 11:45 AM 7 Day NICO & VINZ Please set all print margins to 0.50 Song Analysis Am I Wrong Warner Bros. Mediabase - All Stations (U.S.) - by Format LW: May 13 - May 19 TW: May 20 - May 26 Updated: Tue May 27 3:17 AM PST N Sng Rnk Spins Station (Click Graphic for Mkt e @Station Market Format Trade TW lw +/- -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 -7to Airplay Trends) Rank w (currents) Date KDWB-FM * 1 16 Minneapolis Top 40 Mediabase 114 70 44 19 15 13 16 17 16 18 453 WZEE-FM * 5 99 Madison, WI Top 40 Mediabase 80 36 44 13 9 11 13 10 13 11 264 WXXL-FM * 3 33 Orlando Top 40 Mediabase 78 73 5 12 8 9 12 12 13 12 326 WKCI-FM * 5 121 New Haven, CT Top 40 Mediabase 77 40 37 14 8 8 12 13 15 7 292 WFBC-FM * 8 59 Greenville, SC Top 40 Mediabase 73 69 4 10 10 11 10 11 10 11 367 WNOU-FM * 10 40 Indianapolis Top 40 Mediabase 73 63 10 9 10 9 11 12 10 12 319 WVHT-FM * 9 43 Norfolk Top 40 Mediabase 71 34 37 10 9 9 10 11 11 11 199 WKXJ-FM * 6 107 Chattanooga Top 40 Mediabase 69 40 29 13 6 6 14 12 12 6 210 KMVQ-FM * 6 4 San Francisco Top 40 Mediabase 67 68 -1 10 8 7 11 11 10 10 384 KFRH-FM * 11 32 Las Vegas Top 40 Mediabase 67 65 2 9 8 10 9 10 11 10 420 WXZO-FM * 13 143 Burlington, VT Top 40 Mediabase 66 44 22 11 7 8 10 11 11 8 228 KBFF-FM * 5 23 Portland, OR Top 40 Mediabase 65 72 -7 7 8 7 10 12 10 11 327 KREV-FM 9 4 San Francisco Top 40 Mediabase 65 60 5 9 9 12 9 9 9 8 192 WDJX-FM * 5 54 Louisville Top 40 Mediabase 64 61 3 10 9 10 10 8 9 8 318 WKSC-FM * 10 3 Chicago Top 40 Mediabase 63 38 25 10 7 9 9 10 9 9 200 WJHM-FM * 10 33 Orlando Top -

Review of Fakazatune.Com Generated on 2020-05-02

78 Your Website Score Review of Fakazatune.com Generated on 2020-05-02 Introduction This report provides a review of the key factors that influence the SEO and usability of your website. The homepage rank is a grade on a 100-point scale that represents your Internet Marketing Effectiveness. The algorithm is based on 70 criteria including search engine data, website structure, site performance and others. A rank lower than 40 means that there are a lot of areas to improve. A rank above 70 is a good mark and means that your website is probably well optimized. Internal pages are ranked on a scale of A+ through E and are based on an analysis of nearly 30 criteria. Our reports provide actionable advice to improve a site's business objectives. Please contact us for more information. Table of Contents Search Engine Optimization Usability Mobile Technologies Visitors Social Link Analysis Iconography Good Hard to solve To Improve Little tough to solve Errors Easy to solve Not Important No action necessary Copyright © 2021 sitescorechecker.com Page 1/26 Search Engine Optimization Title Tag FAKAZA | 2020 MP3 MUSIC | SONGS & ALBUMS DOWNLOAD Length: 49 character(s) Ideally, your title tag should contain between 10 and 70 characters (spaces included). Make sure your title is explicit and contains your most important keywords. Be sure that each page has a unique title. Meta Description The Best Place to Download Latest South African Entertainment including Afro House Music, Amapiano, Gqom, Kwaito,Soulful, Deep house, hip hop, MP3 & Videos. Length: 156 character(s) Meta descriptions contains between 100 and 300 characters (spaces included). -

128901439.Pdf

the carillon The University of Regina Students’ Newspaper since 1962 Mar. 7 - 13, 2013 | Volume 55, Issue 22 | carillonregina.com cover The City of Regina has been on the staff a relentless revitalization project for the past few years, in other editor-in-chief dietrich neu [email protected] words, screwing up everything. business manager shaadie musleh The latest project laden with [email protected] production manager julia dima controversy is the demolition [email protected] copy editor michelle jones and rebuilding of Connaught [email protected] elementary school. Read about news editor taouba khelifa [email protected] the plans on page 6. And you a&c editor paul bogdan [email protected] have a lovely day. sports editor autumn mcdowell [email protected] op-ed editor edward dodd [email protected] visual editor arthur ward [email protected] ad manager neil adams [email protected] news arts & culture technical coordinator jonathan hamelin [email protected] news writer kristen mcewen sophie long a&c writer kyle leitch sports writer braden dupuis photographers olivia mason marc messett tenielle bogdan emily wright Growing together. 4 Con-no more. 6 Regina’s Seedy Saturday Continuing Regina's heritage contributors this week regan meloche joel blechinger jordan palmer brought together experts, gar- of tearing down its heritage, michael chmielewski paige kreutzwieser kevin chow deners, local business owners, the Board of Education voted and organizations, all looking to tear down and rebuild the forward to the start of spring 100 year old Connaught the paper and the planting season. School despite outcry from THE CARILLON BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gardening is more than just the community. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

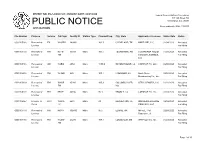

REPORT NO. PN-1-200207-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/07/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000105266 Renewal of FX W267BI 140992 101.3 CLEVELAND, TN HARTLINE, LLC 02/04/2020 Accepted License For Filing 0000101150 Renewal of FM KTFS- 33541 Main 107.1 TEXARKANA, AR TEXARKANA RADIO 01/28/2020 Accepted License FM CENTER LICENSES, For Filing LLC 0000105186 Renewal of AM WJBO 4054 Main 1150.0 BATON ROUGE, LA CAPSTAR TX, LLC 02/03/2020 Accepted License For Filing 0000104916 Renewal of FM WHMD 680 Main 107.1 HAMMOND, LA North Shore 02/03/2020 Accepted License Broadcasting Co., Inc. For Filing 0000103393 Renewal of FM WACR- 65200 Main 105.3 COLUMBUS AFB, GTR LICENSES, LLC 01/31/2020 Accepted License FM MS For Filing 0000105191 Renewal of FM KRVE 40866 Main 96.1 BRUSLY, LA CAPSTAR TX, LLC 02/03/2020 Accepted License For Filing 0000105367 License To DTV WXPX- 6601 Main 29 BRADENTON, FL ION MEDIA LICENSE 02/04/2020 Accepted Cover TV COMPANY, LLC For Filing 0000105159 Renewal of FM KOYH 190430 Main 95.5 ELAINE, AR Alfred L. 'Pat' 02/03/2020 Accepted License Roberson , III . For Filing 0000101180 Renewal of FM WLSM- 26238 Main 107.1 LOUISVILLE, MS WH Properties, Inc. 01/28/2020 Accepted License FM For Filing Page 1 of 30 REPORT NO. PN-1-200207-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/07/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. -

Audio Streams up 15%, Vinyl Sales Double in First Half of 2021

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE JULY 14, 2021 Page 1 of 18 INSIDE Audio Streams Up 15%, Vinyl Sales • Walter Kolm’s WK Double in First Half of 2021 Records Expands, Hires New CEO and BY ED CHRISTMAN Launches Mexican Imprint As the pandemic ends, the recorded music business million streams. (By comparison, Roddy Ricch’s “The has continued to thrive: overall on-demand streams in Box” had been streamed 1.07 billion times during the • Venues Won’t Have to Reapply the U.S. grew 10.8%, to 555.3 billion, in the first half of first half of last year.) for Supplemental 2021 compared to the same period of 2020, according The top album is Morgan Wallen’s Dangerous: The Shuttered Venue to MRC Data. Within that audio streams grew 15% to Double Album, with 2.1 million album consumption Grants nearly 483 billion from nearly 420 million in the cor- units, outpacing the No. 2 title, Olivia Rodrigo’s SOUR, • Why Picking a responding earlier period and globally audio streams at 1.37 million units. Wallen’s album is also outper- New Britney Spears performed even better jumping a whopping 27.3% to forming last year’s mid-year No. 1, Lil Baby’s My Turn, Conservatorship 1.296 trillion. which had nearly 1.5 million album consumption units Lawyer Isn’t So Not all the good news is digital. Vinyl sales, which by this time. Simple have grown for the past decade, more than doubled Taylor Swift’s evermore leads vinyl sales over the • 2021 Billboard Latin between January and June, up 108.2% to 19.2 million period, with 143,000 units sold, followed by Harry Music Awards Date & from 9.2 million in the first six months of last year. -

Tim Holden and Jaco Koekemoer of Caxton Local Media Support the Needy During the CEO Sleepout in Late July

AUG 2016 / FREE! A CAXTONCAXTON PUBLICATIONPUBLICATION Cold hands, warm hearts Tim Holden and Jaco Koekemoer of Caxton Local Media support the needy during the CEO SleepOut in late July. TAKE A STAND: Tim Holden, group managing director of Caxton Printers and Publishers and Jaco Koekemoer, managing director of Caxton Local Media warm up at the CEO SleepOut in Braamfontein. SEE PAGE 8 LIBERTY FOR MISS INDIA THE CEO FOX PRECINCT MANDELA 212 AIMS HIGH 612 SLEEPOUT 812 IS REVAMPED 1412 AFHCO/9840/E Stuttafords Apartments pmPriced from For a home you can call your own. afhco.co.za 087 075 1228 | [email protected] 2 • August 2016 CITYBUZZ Art of Life: Teaming up to showcasing Stop Hunger Now RACINE EDWARDES centres acrosss the countrycountry. [email protected] More than 900 staff members participated young talent in four shifts of 67 minutes, where teams from A leading corporate incorporates all their staff various departments put all their efforts CITY REPORTER into their 67 Minutes for Mandela DaDayy in pputtingu together food parcels efforts. concontaining rice and soya, [email protected] The Liberty Group, based in aamong other food staples Hard work required for a hearty, filling New Acropolis South Africa, an international Braamfontein, teamed up with Stop diet. non-governmental organisation has launched the Hunger Now SA to get all hands to give “We are targeting to Art of Life youth art exhibition as part of its 10- on deck and working at full force to back to pack 100 000 meals, which year anniversary celebration in Braamfontein.