The William Brewster Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives Cape Cod Community College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan

Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan Volume 2 Baseline Assessment and Science Framework December 2009 Introduction Volume 2 of the Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan focuses on the data and scientific aspects of the plan and its implementation. It includes these two separate documents: • Baseline Assessment of the Massachusetts Ocean Planning Area - This Oceans Act-mandated product includes information cataloging the current state of knowledge regarding human uses, natural resources, and other ecosystem factors in Massachusetts ocean waters. • Science Framework - This document provides a blueprint for ocean management- related science and research needs in Massachusetts, including priorities for the next five years. i Baseline Assessment of the Massachusetts Ocean Management Planning Area Acknowledgements The authors thank Emily Chambliss and Dan Sampson for their help in preparing Geographic Information System (GIS) data for presentation in the figures. We also thank Anne Donovan and Arden Miller, who helped with the editing and layout of this document. Special thanks go to Walter Barnhardt, Ed Bell, Michael Bothner, Erin Burke, Tay Evans, Deb Hadden, Dave Janik, Matt Liebman, Victor Mastone, Adrienne Pappal, Mark Rousseau, Tom Shields, Jan Smith, Page Valentine, John Weber, and Brad Wellock, who helped us write specific sections of this assessment. We are grateful to Wendy Leo, Peter Ralston, and Andrea Rex of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority for data and assistance writing the water quality subchapter. Robert Buchsbaum, Becky Harris, Simon Perkins, and Wayne Petersen from Massachusetts Audubon provided expert advice on the avifauna subchapter. Kevin Brander, David Burns, and Kathleen Keohane from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection and Robin Pearlman from the U.S. -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Cape Ann Light

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAPE ANN LIGHT STATION (Thacher Island Twin Lights) Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Cape Ann Light Station Other Name/Site Number: Thacher Island Twin Lights 2. LOCATION Street & Number: One mile off coast of Rockport, Massachusetts. Not for publication: City/Town: Rockport Vicinity: X State: MA County: Essex Code: 009 Zip Code: 01966 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 buildings sites 2 2 structures objects 6 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 6 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: n/a (see summary context statement for Lighthouse NHL theme study) NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAPE ANN LIGHT STATION (Thacher Island Twin Lights) Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The Too Much Married Keeper

April 2020 Newsletter Thacher & Straitsmouth Island News VOL 20 ISSUE 01 Photo by Chris Spittle of Cape Ann Weather NEW BOOK The Saving Straitsmouth - A History Too Much TO BE PUBLISHED NEXT MONTH Married President Paul St. Germain has written his fifth book on historical sites of Cape Ann. This one is a comprehensive history of Straitsmouth Island Keeper in Rockport. Just off the coast of Rockport, Massachusetts, Linda Josselyn was gone. Straitsmouth Island has enjoyed a noteworthy history that belies the island’s small size. From the Pawtucket When assistant keeper Asa Indians who summered there over a thousand years Josselyn ended his shift in ago to its discovery by famous explorers Samuel De Champlain and Captain John Smith in the seventeenth the North Tower at 4 a.m. on century, it has seen fishermen, shipwrecks and piracy. November 1, 1903, he found The island also played a key role in the development of the commercial fishing industry on Cape Ann. his two children asleep and From 1835 to 1935, there were three lighthouses Linda Josselyn’s photo in the a note from his wife, strongly built there, each with its own fascinating story of the Boston Globe, November 11, 1903. implying that she intended to lighthouse keepers and their families. He recounts the lives of many of the fifteen keepers who lived on throw herself into the sea. the island from 1835 until 1933.Thanks to tireless He roused the other keepers, a search was made, but no body was restoration efforts by the Thacher Island Association found. -

Trip Planner U.S

National Park Service Trip Planner U.S. Department of the Interior Cape Cod National Seashore Seasonal listings of activities, events, and ranger programs are available at seashore visitor centers. NPS/MCQUEENEY Park Information Superintendent’s Message Cape Cod National Seashore Oversand Office at Race Point Mention Cape Cod National 99 Marconi Site Road Ranger Station Seashore and different thoughts Wellfleet, MA 02667 Route Information: come to mind. Certainly, for Superintendent: Brian Carlstrom 508-487-2100, ext. 0926 many, the national seashore is Email: [email protected] (April 15 through November 15) “the beach”—a place to recreate, rejuvenate, and forge lasting Park Headquarters, Wellfleet Permit Information: memories with family and friends. 508-771-2144 508-487-2100, ext. 0927 Other people are attracted to Fax: 508-349-9052 nature’s wildness. Change is an North Atlantic Coastal Lab ever-present force on the Outer Nauset Ranger Station, Eastham 508-487-3262 Cape, with wind, waves, and 508-255-2112 storms constantly shaping and reshaping the land. As the longest Emergencies: 911 NPS/KEKOA ROSEHILL Race Point Ranger Station, Provincetown continuous stretch of shoreline 508-487-2100 https://www.nps.gov/caco on the East Coast, the national seashore doesn’t just host sun-loving humans; it provides a refuge Salt Pond Visitor Center Province Lands Visitor Center for many species, including threatened shorebirds. Salt marshes and forests support a diverse array of plants and animals. And off-shore, Open daily from 9 am to 4:30 pm (later during Open daily from 9 am to 5 pm, mid-April to the ocean teems with life, including the microscopic plankton that the summer). -

Portsmouth Harbor Beacon Newsletter of the Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, a Chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation

Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse / Whaleback Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Beacon Newsletter of the Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, a chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation www.portsmouthharborlighthouse.org / www.lighthousefoundation.org Quarterly Newsletter Summer 2012 A Record-Setting Season The Things Kids Say Meet the Gundalow Piscataqua We are on track to smash all previous attendance (As collected by volunteer E. J. Warren during Visitors to Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse records at our Sunday open houses at Portsmouth open houses at Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse.) this season may have noticed a newcomer on Harbor Lighthouse, with an expected total of more the Seacoast maritime scene – the sail vessel than 3000 visitors. Last year’s total was about “The lighthouse is a big green ‘go’ light at night Piscataqua. This picturesque boat, now 2400. Even with less than ideal weather some for boats!” carrying passengers on public sails from weeks, there have been around 150 or more Portsmouth’s Prescott Park, is a replica of the visiting just about every Sunday, peaking with 214 “That's a sad lighthouse out there (Whaleback), flat-bottomed sail barges that carried freight on August 26 and 215 on September 2. with no one to visit it.” on the waterways of our region for hundreds of years. “My daddy calls my mommy a keeper, but we ain't got no lighthouse.” “Do you know where the sea horses are?” On August 30, 2012, historic preservation We typically staff our open houses with at least architect Deane Rykerson and lighthouse five volunteers, with a merchandise table and historian Jeremy D’Entremont were the guest various positions inside and outside the lighthouse. -

Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound

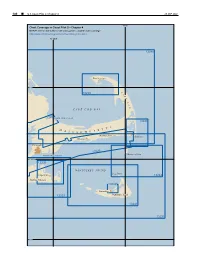

186 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 26 SEP 2021 70°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 4 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 70°30'W 13246 Provincetown 42°N C 13249 A P E C O D CAPE COD BAY 13229 CAPE COD CANAL 13248 T S M E T A S S A C H U S Harwich Port Chatham Hyannis Falmouth 13229 Monomoy Point VINEYARD SOUND 41°30'N 13238 NANTUCKET SOUND Great Point Edgartown 13244 Martha’s Vineyard 13242 Nantucket 13233 Nantucket Island 13241 13237 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 ¢ 187 Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound (1) This chapter describes the outer shore of Cape Cod rapidly, the strength of flood or ebb occurring about 2 and Nantucket Sound including Nantucket Island and the hours later off Nauset Beach Light than off Chatham southern and eastern shores of Martha’s Vineyard. Also Light. described are Nantucket Harbor, Edgartown Harbor and (11) the other numerous fishing and yachting centers along the North Atlantic right whales southern shore of Cape Cod bordering Nantucket Sound. (12) Federally designated critical habitat for the (2) endangered North Atlantic right whale lies within Cape COLREGS Demarcation Lines Cod Bay (See 50 CFR 226.101 and 226.203, chapter 2, (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are for habitat boundary). It is illegal to approach closer than described in 33 CFR 80.135 and 80.145, chapter 2. -

Joppa Flats Summer Camp!

table of contents North Shore Wildlife Sanctuaries Map Marketing Department and Contact Information . Inside Front Cover Mass Audubon 208 South Great Road, Lincoln, MA 01773 Notes & Announcements . 2-3 781-259-2135 [email protected] Cover photos: Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary Programs Yellow Warbler at Ipswich River—Carol Decker© Adult and Special Event . 4-9 Kayakers Exploring in Plum Island Sound— Children & Families . 10-17 Walt Thompson© © Fragrant Water Lily at Ipswich River—Jeanne Li Joppa Flats Education Center Programs Great Spangled Fritillary—Scott Santino© Adult . 18-26 Back cover photo: Birders—Melissa Vokey© Children, Families, & All Ages . 27-29 Ipswich River Preschool Logo: Trips and Tours . 30-34 Victor Atkins© General Information . 35 Printing: DS Graphics Funding provided in part by: Registration Procedures & Policy Guidelines . 36 Registration Form . Inside Back Cover Register Online! You can register for many of Mass Audubon’s programs online. See page 36 for details. Explore the outdoors at Joppa Flats Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary Summer Camp! Day Camp Programs Creative and fun nature day camps for children ages 4-14 for children ages 6 to 13 NEW in 2016: Full weeks • Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary, Topsfield and aftercamp care! • Hamond Nature Center, Marblehead • 5-day camp sessions for ages 6 to 11 with excursions • Essex County Greenbelt Association’s to varied habitats by motor, foot, and boat Cox Reservation, Essex • 5-day adventure-based ecology camp for ages 11 to 13 For more information, see page 29. For a camp brochure, call 978-887-9264 or For a camp brochure, visit www.massaudubon.org/joppaflats download a copy: www.massaudubon.org/ipswichrive r or call Kirsten Lindquist at 978-462-9998 x6805. -

Destruction Island Light, Washington

National Wildlife Refuge System Lighthouses More than two dozen lighthouses stand on U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service land managed by national wildlife refuges. Another half-dozen are often associated with a refuge but are not on U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service land. All can be seen from the outside; the inside of some is open to limited public visitation. Check with individual refuges for details. Most websites listed are unofficial, non-U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sites. Pacific and Pacific Southwest Regions: Owned by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Daniel K. Inouye Kilauea Point Lighthouse Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge, Hawaii. http://www.fws.gov/nwrs/threecolumn.aspx?id=2147549718 http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=139 Destruction Island Lighthouse Quillayute Needles National Wildlife Refuge, Washington. http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=118 New Dungeness Lighthouse Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge System, Washington. http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Dungeness/visit/visitor_activities.html http://newdungenesslighthouse.com/ Farallon Island Lighthouse Farallon National Wildlife Refuge, California. http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=100 Smith Island Lighthouse Washington Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Washington. [Archaeological site; structures collapsed and fell into sea] http://www.lighthousedigest.com/Digest/database/uniquelighthouse.cfm?value=1617 Not U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service-owned but Often Associated With a Refuge Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, Oregon http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=135 Cape Meares Lighthouse, Oregon http://www.capemeareslighthouse.org/ Southwest Region: Owned by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Matagorda Lighthouse Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas http://www.matagordalighthouse.com/ http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Aransas/about/matagorda.html Midwest Region: Owned by U.S. -

Epa Contract No

U.S. Department of the Interior Appendix A Minerals Management Service MM S Figures, Maps and Tables Table 4.3.4-1 Historic Properties and Districts Assessed for Wind Park Visibility for the Cape Wind Project Site, Location MHC No. Potential Viewpoint Visual (shown on Figure 5.10-1); Field Visit Visibility Distance to WP Simulation Historic Designation Of WP CAPE COD Town of Falmouth Nobska Point Light Station, Woods Hole Yes Yes VP 1 Yes FAL.LF (S/NRHP) 13.4 Miles ESE Woods Hole Historic District Yes Limited VP 2 No Near Little Harbor, Woods Hole; FAL.AL (local) 13.4 Miles ESE Woods Hole School, 24 School Street; Woods Hole; FAL.428 Yes No VP 3 No (S/NRHP) 14.1 Miles ESE East Falmouth Historic District at Yes No VP 4 No 481 Davisville Road; Falmouth; FAL.AF (local) 8.9 Miles ESE Falmouth Heights Historic District(2) Yes Yes 10.7 Miles SSE No Falmouth, FAL.I (S/NRHP) Maravista Historic District(2) Yes Yes 10.0 Miles SSE No Falmouth, FAL.K (S/NRHP) Menahaunt Historic District(2) Yes Yes 8.4 Miles SSE No Falmouth, FAL.J (S/NRHP) Church Street Historic District(2) Yes Yes VP1 Yes Falmouth, FAL.M (S/NRHP) 13.6 Miles SSE Town of Barnstable Cotuit Historic District(1) Yes Yes VP 5 Yes At 249 Ocean View Avenue; Cotuit BRNK.HD (S/NRHP) 5.7 Miles SE Col. Charles Codman Estate No: Expected 6.0 Miles Yes Same as 43 Ocean Avenue, Cotuit; BRN.367 (S/NRHP) Posted SSE above Wianno Historic District(1) Yes Yes VP 6 Yes At 71 Seaview Avenue, Osterville; BRN.J (S/NRHP) 5.3 Miles SSE Wianno Club, Historic Property Yes Yes VP 6 Yes Same as 107 Seaview Avenue, -

A Springtime Exploration of Essex County's Coastal Islands, With

bo33-1:BO32-1.qxd 6/2/2011 6:26 AM Page 12 A Springtime Exploration of Essex County’s Coastal Islands, with Notes on Their Historical Use by Colonially Nesting Birds Jim Berry For over thirty years I have lived on the North Shore of Massachusetts without a boat and have long wondered what colonially nesting birds, in what numbers, have nested on the many islands along the Essex County coast. All I knew was that large gulls and cormorants nest on some of them, that terns used to nest on them, and that herons have used at least three of them, but beyond that I didn’t know many details. In 2004 I got a chance to learn more when I found out that my friends Mary Capkanis and Dave Peterson had acquired a boat, and that Mary had obtained a pilot’s license. Both are longtime birders, and both have experience surveying waterbird colonies in various parts of the U.S. Finally, I had the means to do some island- hopping with friends who were serious about surveying for nesting birds. We made three outings, on May 12, May 14, and May 31. Linda Pivacek accompanied us on the third trip. We were unable to get out in June and of course needed more trips, later in the nesting season, to complete even a preliminary census. But in those three days we visited (with very few landings) most of the 30+ islands between Rockport and Nahant that are large enough to support nesting birds. I had three goals for these trips: (1) to see where gulls and cormorants are nesting and in roughly what numbers, and whether terns still nest on any of the islands; (2) to find out whether herons are currently nesting on any islands other than Kettle, off Manchester; and (3) to look for evidence of nesting by other species, such as Common Eiders (Somateria mollissima), which have increased dramatically as nesters in Boston Harbor, and Great Cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), Black Guillemots (Cepphus grylle), and American Oystercatchers (Haematopus palliatus), for which there are no documented nesting records in Essex County. -

Chatham Reconnaissance Report ______

CHATHAM RECONNAISSANCE REPORT _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Cape Cod Landscape Inventory Massachusetts Heritage Landscape Inventory Program ____________________________________________________ Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Cape Cod Commission Boston University 1 PROJECT TEAM _____________________________________________________________________________________ Boston University Preservation Studies Graduate Students Erin A. Chapman, Kate Leann Gehlke, Leo M. Greene, Amie K. Schaeffer Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) Jessica Rowcroft, Preservation Planner Cape Cod Commission (CCC) Sarah Korjeff, Preservation Planner Gary Prahm, GIS Analyst Boston University Preservation Studies Program Eric Dray, Lecturer Local Project Coordinators (LPCs) Donald Aikman and Frank Messina, Chatham Historical Commission Local Heritage Landscape Participants Donald Aikman, Chatham Historical Commission* Bill Appleford, Friends of Chatham Waterways Barbara Cotnam, Chatham Marconi Maritime Center* Emily Cunningham D. Ecker, Friends of Chatham Waterways Dean Ervin, South Coast Harbor Planning Commission Gloria Freeman, West Chatham Association* Mary Ann Gray, Chatham Historical Society* Spencer Grey* Richard Gulick, Chatham Planning Board* John Halgran Donna Lumpkin, Chatham Marconi Maritime Center Nat Mason Frank Messina, Chatham Historical Commission* Cory Metters, Chatham Planning Board Jane Moffett, Community Preservation -

U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office

U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office Preserving Our History For Future Generations Historic Light Station Information MASSACHUSETTS Note: Much of the following historical information and lists of keepers was provided through the courtesy of Jeremy D'Entremont and his website on New England lighthouses. ANNISQUAM HARBOR LIGHT CAPE ANN, MASSACHUSETTS; WIGWAM POINT/IPSWICH BAY; WEST OF ROCKPORT, MASSACHUSETTS Station Established: 1801 Year Current/Last Tower(s) First Lit: 1897 Operational? YES Automated? YES 1974 Deactivated: n/a Foundation Materials: STONE Construction Materials: BRICK Tower Shape: CYLINDRICAL ATTACHED TO GARAGE Height: 45-feet Markings/Pattern: WHITE W/BLACK LANTERN Characteristics: White flash every 7.5 seconds Relationship to Other Structure: ATTACHED Original Lens: FIFTH ORDER, FRESNEL Foghorn: Automated Historical Information: * 1801: Annisquam is the oldest of four lighthouses to guard Gloucester peninsula. The keeper’s house, built in 1801 continues to house Coast Guard families. Rudyard Kipling lived there while writing "Captain’s Courageous" – a great literary tribute to American sailors. * 1974: The 4th order Fresnel lens and foghorn were automated. Page 1 of 75 U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office Preserving Our History For Future Generations BAKERS ISLAND LIGHT Lighthouse Name: Baker’s Island Location: Baker’s Island/Salem Harbor Approach Station Established: 1791 Year Current/Last Tower(s) First Lit: 1821 Operational? Yes Automated? Yes, 1972 Deactivated: n/a Foundation Materials: Granite Construction Materials: Granite and concrete Tower Shape: Conical Markings/Pattern: White Relationship to Other Structure: Separate Original Lens: Fourth Order, Fresnel Historical Information: * In 1791 a day marker was established on Baker’s Island. It was replaced by twin light atop the keeper’s dwelling at each end in 1798.